Published October 26, 2023. Updated January 12, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Giant Whiptail (Ameiva ameiva)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Teiidae | Ameiva ameiva

English common name: Giant Whiptail.

Spanish common name: Lagartija corredora mayor.

Recognition: ♂♂ 56 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=14.9 cm. ♀♀ 47.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=12.0 cm..1 The Giant Whiptail (Ameiva ameiva) differs from other medium-sized, striped diurnal and terrestrial lizards in the Ecuadorian Amazon by having granular dorsal scales, smooth ventral scales organized in eight rows, and plate-like scales on the head.1–3 Adult males are easily recognizable by their large size, broad head, and dorsal coloration that shifts from brown on the head to green on the dorsum.2 Females and juveniles are brown with cream stripes and spots (Fig. 1).1,2 The most similar whiptail that may be found living alongside A. ameiva in the Ecuadorian Amazon is Kentropyx pelviceps, which is distinguishable by its broad vertebral stripe that transitions from green to copper, with undulating margins that widen posteriorly.4,5

Figure 1: Individuals of Ameiva ameiva from Yarina Lodge, Orellana province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Ameiva ameiva is a locally abundant whiptail that inhabits semi-open areas in old growth to moderately disturbed rainforests, which may be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.2,5,6 The species seems to prefer more open habitats than Kentropyx pelviceps, being found mostly on clearings, tree-fall areas,5 forest edges, plantations,7 pastures,8 and peri-urban areas.1,2,9 Giant Whiptails require extended periods of direct sunlight to become active,5 typically being out during late sunny mornings to early afternoons when temperatures exceed 26°C.2,5,10 On cloudy days, they remain concealed.2 At night, Giant Whiptails seek shelter in holes or beneath logs.1,2 Their home burrow is usually surrounded by bare soil but usually nearby cover.9,11 They are primarily terrestrial but also may bask on logs and dead limbs up to 1.5 m above the ground.5 The majority of their active time is spent basking on filtered sunlight or frantically foraging, essentially never stopping as they noisily scratch in search for food.1,9 Their diet is opportunistic and includes arthropods (particularly grasshoppers, roaches, mole crickets, and caterpillars), but also lizards (such as Gonatodes concinnatus,2 Copeoglossum nigropunctatum,2 and even conspecifics12),13 amphisbaenians,14 snails, and plant matter.1,10,11 Giant Whiptails rely mostly on their wariness and sprint speed as defense mechanisms, but they may bite or readily shed the tail if captured.1,9 There are documented instances of predation on individuals of this species by snakes (Boa constrictor,11 Corallus hortulana,15 Clelia clelia,2 Drymarchon corais,11 Drymoluber dichrous,16 Erythrolamprus aesculapii,17 E. reginae,18 Oxybelis fulgidus,19 Pseudoboa coronata,2 Siphlophis compressus,18 Xenodon severus,11 and Bothrops atrox1), lizards, hawks,6,11 and ocelots.20 Reproduction in Ecuador seems to occur annually for a period of six months.2 Females lay clutches of 1–11 (usually 4) eggs10 in nests excavated in sand or soft soil, with an incubation period of 129–140 days (~4–5 months).2,8,21,22

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..23 Ameiva ameiva is listed in this category because the species has a wide distribution and it is comparatively common and abundant in most areas.23 Moreover, nearly half of its occurrence in the Brazilian Amazon falls within designated protected areas.24 Observations in Brazil indicate a growing abundance of this species as a response to the conversion of dense-canopy rainforests into selectively logged semi-open environments.25

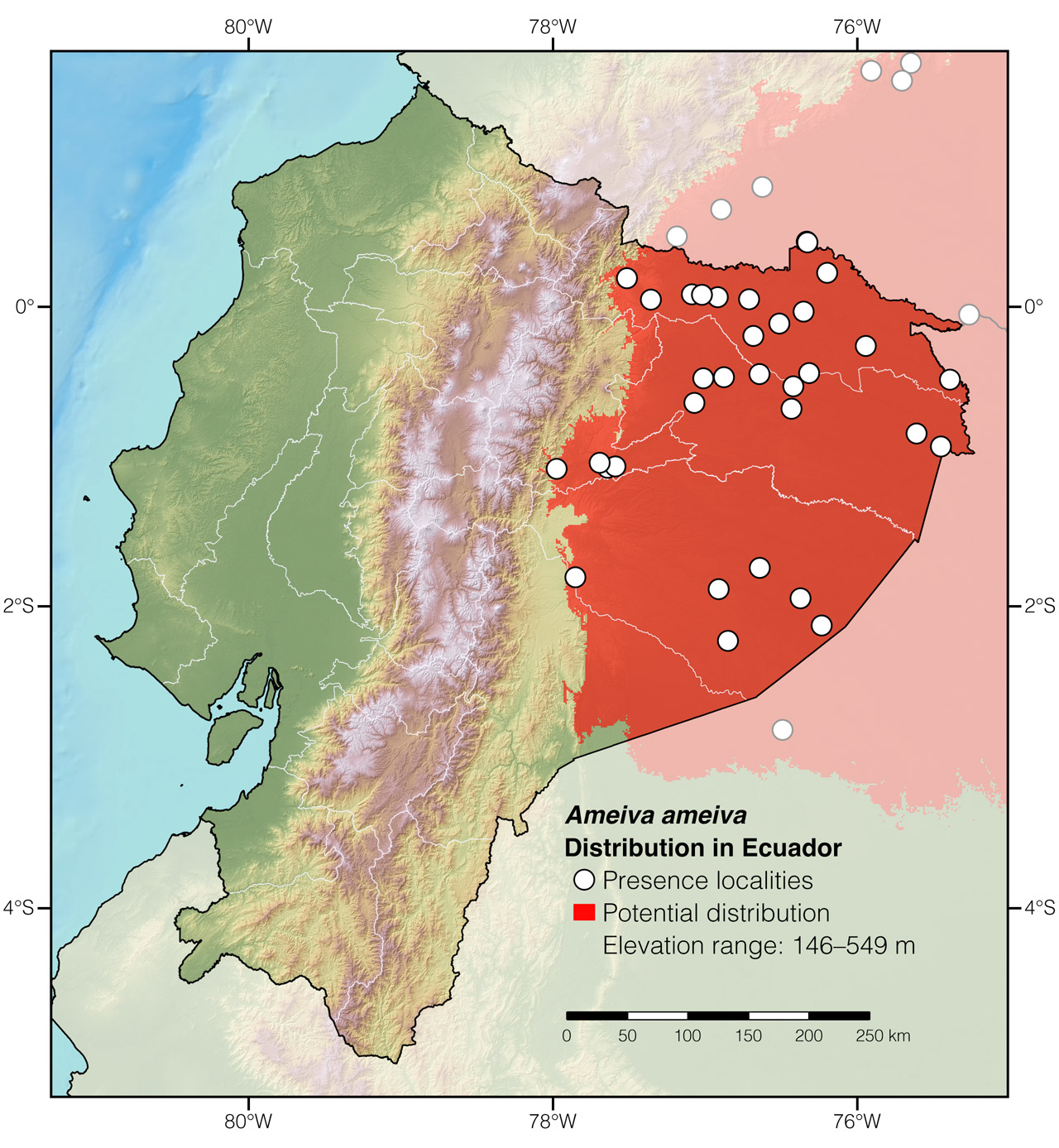

Distribution: Ameiva ameiva is widely distributed throughout northern South America, including the entire Amazon basin in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), French Guiana, Guyana, Perú, Suriname, and Venezuela. The species also occurs in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, in the Brazilian Cerrado, and El Chaco plains in Argentina and Paraguay.26 However, as currently understood, A. ameiva is a species complex rather than a single species.3

Figure 2: Distribution of Ameiva ameiva in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The word Ameiva is of Tupí language origin and is the name Amerindian peoples in 17th century Dutch Brazil used to refer to these lizards.27

See it in the wild: Giant Whiptails are comparatively easy sightings within their distribution range in Ecuador, especially in Yarina Lodge and Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve. These jittery reptiles can be readily observed running on the floor in forest-edge situations during warm sunny days.

Special thanks to Santiago Castroviejo for symbolically adopting the Giant Whiptail and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Giant Whiptail (Ameiva ameiva). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/PKVG5869

Literature cited:

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Harvey MB, Ugueto GN, Gutberlet Jr RL (2012) Review of teiid morphology with a revised taxonomy and phylogeny of the Teiidae (Lepidosauria: Squamata). Zootaxa 3459: 1–156. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3459.1.1

- Gallagher DS, Dixon JR (1992) Taxonomic revision of the South American lizard genus Kentropyx Spix (Sauria: Teiidae). Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino 10: 125–171.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Hoogmoed MS (1973) Notes on the herpetofauna of Surinam. IV. The lizards and amphisbaenians of Surinam. Biogeographica 4: 1–419.

- Fitch HS (1968) Temperature and behavior of some equatorial lizards. Herpetologica 24: 35–38.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Vanzolini PE (1972) Miscellaneous notes on the ecology of some Brazilian lizards (Sauria). Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 26: 83–115.

- Vitt LJ, Colli GR (1994) Geographical ecology of a neotropical lizard: Ameiva ameiva (Teiidae) in Brazil. Canadian Journal of Zoology 72: 1986–2008.

- Beebe W (1945) Field notes on the lizards of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Part 3. Teiidae, Amphisbaenida, and Scincidae. Zoologica 30: 7–32.

- Nino K, Ribeiro S, Santos E (2011) The curious, first record of cannibalism in Ameiva ameiva Linnaeus, 1758 (Squamata: Teiidae) in northeastern Brazil. Herpetology Notes 14: 465–468.

- Sales RFD, Ribeiro LB, Almeida HWB, Freire EMX (2010) Ameiva ameiva (Giant Ameiva): saurophagy. Herpetological Review 41: 72–73.

- Kulaif Ubaid F, Rodrigues do Nascimento G, Maffei F (2009) Ameiva ameiva (Green Lizard): attempted predation of amphisbaenian. Herpetological Review: 339.

- Pizzatto L, Marques OAV, Facure K (2009) Food habits of Brazilian boid snakes: overview and new data, with special reference to Corallus hortulanus. Amphibia-Reptilia 30: 533–544. DOI: 10.1163/156853809789647121

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Lopes Santos D, Vaz-Silva W (2012) Predation of Phimophis guerini and Ameiva ameiva by Erythrolamprus aesculapii (Snake: Colubridae). Herpetology Notes 5: 495–496.

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- Fischer WA, Gascon C (1996) Oxybelis fulgidus (Green Vine Snake): feeding behavior. Herpetological Review 27: 204.

- Correa Branco A, Bordignon MO, Rufino de Albuquerque N (2019) Ameiva ameiva (Giant Ameiva): predation. Herpetological Review 50: 133.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- McCrystal HK, Behler JL (1982) Husbandry and reproduction of captive Giant Ameiva lizards at the New York Zoological Park. International Zoo Yearbook 22: 159–163. DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-1090.1982.tb02026.x

- Ibáñez R, Jaramillo C, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Rivas G, Caicedo J, Kacoliris F, Pelegrin N (2014) Ameiva ameiva. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T203180A2761608.en

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Amaral S (2016) Diversity, distribution, and conservation of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) in the Brazilian Amazonia. Neotropical Biodiversity 2: 195–421. DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2016.1236769

- Lima AP, Suárez FIO, Higuchi N (2001) The effects of selective logging on the lizards Kentropyx calcarata, Ameiva ameiva, and Mabuya nigropunctata. Amphibia-Reptilia 22: 209–216.

- Ribeiro-Junior MA, Amaral S (2016) Catalogue of distribution of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Brazilian Amazonia. III. Anguidae, Scincidae, Teiidae. Zootaxa 4205: 401–430. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4205.5.1

- Angeli NF (2018) On ‘lost’ indigenous etymological origins with the specific case of the name Ameiva. ZooKeys 748: 151–159. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.748.21436

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Ameiva ameiva in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Altoros | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Caserío Los Ángeles | Caicedo Portilla 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Macagual | Valderrama 2021 |

| Colombia | Meta | Los Pozos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Nariño | Vereda La Libertad | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Caucayá | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Finca El Escondite | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Guitorra | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | La Paya | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Orito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | FMNH 165192; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loreto | Bretaña | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loreto | Muniches | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guaysayacu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | La Punta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Napo | Cope 1868 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Añangu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo ITT | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Hotel La Misión | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Las Palmas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Rocafuerte | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pompeya | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arutam, environs of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Boca del Río Cuyabeno | USNM 201435; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Jambelí | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lagartococha | Usma et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puca Peña | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente del Cuyabeno | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Libre | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa–Dureno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | Loreto | Campo Andoas | Valqui Schult 2015 |

| Perú | Loreto | Cerro de Kampankis | Catenazzi & Venegas 2016 |