Published April 15, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Yellowtail Cribo (Drymarchon corais)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Drymarchon corais

English common names: Yellowtail Cribo, Yellow-tailed Indigo Snake.

Spanish common name: Rabo amarillo.

Recognition: ♂♂ 234.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=192.5 cm. ♀♀ 251 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=209 cm..1,2 Drymarchon corais is a heavy-bodied snake having a unique dorsal coloration (Fig. 1). The head is olive-brown or yellow and the dorsum is dark brown, progressively turning yellow towards the tail.1–4 The juveniles have a pattern of dark oblique crossbars on a light gray dorsum. This species differs from other large diurnal snakes (such as Chironius, Spilotes and Phrynonax) by having smooth dorsal scales.1–4 From Clelia clelia and Xenodon severus, it differs by having a uniformly yellow tail in adults.1,2

Figure 1: Adult male of Drymarchon corais from Loreto department, Perú.

Natural history: Drymarchon corais is a terrestrial and arboreal snake that inhabits a variety of forested and semi-open ecosystems, ranging from pristine rainforests to pastures and cultivated areas.1–5 Yellowtail Cribos forage primarily on the forest floor during sunny days, but they also utilize tree branches up to 5 m above the ground.2,5 They are also frequently observed along roadsides, lakes, rivers, marshes, and swamps.2,5 When not active, they hide among roots or roost on arboreal vegetation.2,5 The diet in this species includes a wide variety of amphibians (even toxic ones such as Rhinella and Leptodactylus),2,5,6 birds and their eggs,3 amphisbaenians (including Amphisbaena alba),7 lizards (including Ameiva ameiva8 and Iphisa brunopereira1), fish, rodents and opossums,6,8 other snakes (notably Erythrolamprus reginae, Bothrops atrox,8 B. taeniatus, and B. colombiensis6), and even opportunistically on carrion.9–11 It is hypothesized that D. corais is immune to the venom of vipers, given its ability to consume them, although studies to prove this are still lacking. This snake exhibits aggressive behavior when cornered, opening its mouth while striking repeatedly.5 Drymarchon corais exhibits a seasonal reproductive pattern, with eggs laid during the local dry season.11–12 Clutches consist of 3–15 eggs, laid in burrows, with an incubation period of approximately 3 months.11–12

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..13 Drymarchon corais is listed in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas, and presumed stable populations.13 However, the destruction and fragmentation of forested environments throughout South America can be a threat for the long-term survival of the species. Individuals of D. corais also suffer from traffic mortality5 and direct killing.14 However, these reptiles are appreciated and even protected in some farming communities for their tendency to feed on venomous snakes as well as on pests such as rats and mice.15

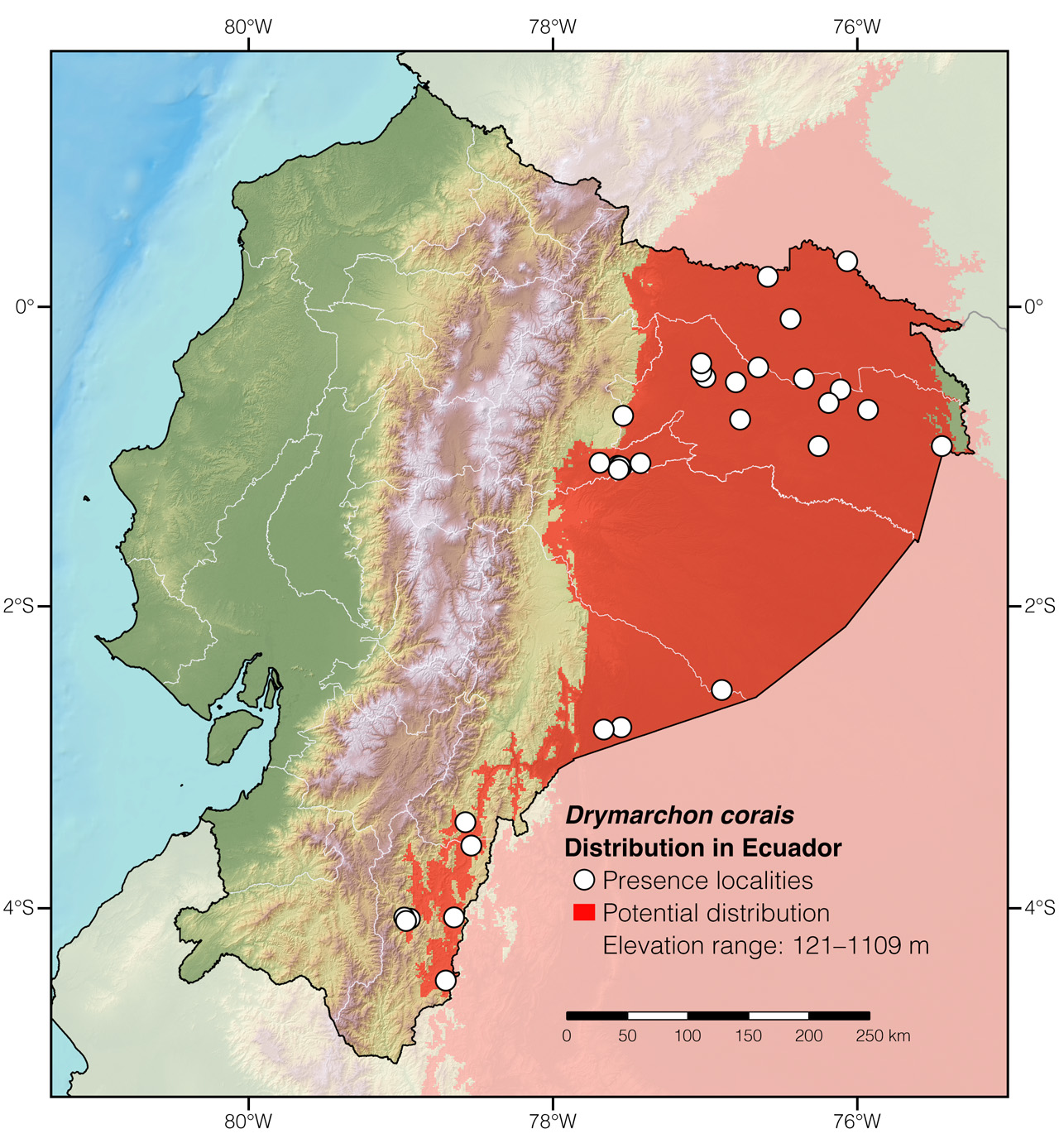

Distribution: Drymarchon corais is native to an area of approximately ~464,577 km2 across much of northern continental South America, as well as in Trinidad and Tobago. The species is widely distributed across the Amazon and adjacent foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.16 It also occurs in the Atlantic Forest of Brazil, in the Brazilian Cerrado and Caatinga, as well as in the El Chaco plains in Argentina, Bolivia, and Paraguay.16

Figure 2: Distribution of Drymarchon corais in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The genus name Drymarchon is derived from the Greek drymos (=oak forest) and archon (=leader),17 and probably refers to the imposing size of this snake. The specific epithet corais comes from the Greek corax (=raven)17 and refers to the dark dorsal coloration.

See it in the wild: Drymarchon corais is considered a rare species in Ecuador, with no more than 1–2 individuals recorded per year at any given locality. The areas having the greatest number of observations of this elusive serpent are Limoncocha Biological Reserve and Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, where individuals are reported as being more abundant along forest-edge situations rather than in deep primary forest.

Special thanks to Gabriella Jaramillo for symbolically adopting the Yellowtail Cribo and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Tatiana Molina-Moreno,aAffiliation: Departamento de Biología, Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. Andrés F. Aponte-Gutiérrez,bAffiliation: Grupo de Investigación en Ciencias de la Orinoquía, Universidad Nacional de Colombia sede Orinoquía, Arauca, Colombia.,cAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. and Danna Duque-TorresdAffiliation: Grupo de Ornitología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Max BenitofAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Molina-Moreno T, Aponte-Gutierrez AF, Duque-Torres D (2024) Yellowtail Cribo (Drymarchon corais). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/BNTK2170

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1978) Ofídios da Amazônia. X. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 31: 1–218.

- Pérez-Santos C, Moreno AG (1988) Ofidios de Colombia. Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali, Torino, 517 pp.

- Dueñas MR, Valencia JH, Franco-Mena D (2021) Update of the geographical distribution of the indigo snake Drymarchon corais (Boie, 1827) in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Avances en Ciencias e Ingenierías 13: 1–14. DOI: 10.18272/aci.v13i2.2170

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Campos VA, Oda FH, Curcino AF, Curcino A (2010) An unusual prey item for the yellow tail cribo Drymarchon corais Boie 1827, in the Brazilian savanna. Herpetology Notes 3: 229–231.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Murphy JC, Downie R, Smith JM, Livingstone S, Mohammed R, Lehtinen RM, Eyre M, Sewlal JN, Noriega N, Casper GS, Anton T, Rutherford MG, Braswell AL, Jowers MJ (2018) A field guide to the amphibians & reptiles of Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad and Tobago Naturalist’s Club, Port of Spain, 336 pp.

- Bernarde PS, Abe AS (2010) Food habits of snakes from Espigão do Oeste, Rondônia, Brazil. Biota Neotropica 10: 167–173.

- da Costa-Prudente AN, Costa A, Magalhães F, Maschio GF (2014) Diet and reproduction of the Western Indigo Snake Drymarchon corais (Serpentes: Colubridae) from the Brazilian Amazon. Herpetology Notes 7: 99–108.

- Boos H (2001) The snakes of Trinidad and Tobago. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 270 pp.

- Ines Hladki A, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N, Nogueira C, Gonzales L, Catenazzi A, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Hoogmoed M, Schargel W, Rivas G, Murphy J (2019) Drymarchon corais. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T62234A3110201.en

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Gorzula S, Señaris CJ (1998) Contribution to the herpetofauna of the Venezuelan Guayana. Scientia Guaianae, Caracas, 305 pp.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Drymarchon corais in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Guainía | Puerto Inírida | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cangaime | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad 13 de Marzo | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Guayabal | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ahuano | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | AmaZoónico | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Anaconda Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pachakutik | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Arajuno | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Boca del Río Coca | KU 158781; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Chiru Isla | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dicaro | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Edén Amazon Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Miwaguno | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nueva Esperanza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Paraíso | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Rocafuerte | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Retiro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Nueva Juventud | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Putumayo | Grant et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Chuchumbletza | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Congüime | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Bombuscaro | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Jamboé | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Nangaritza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Vía al Genairo | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Dueñas et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Marañón | MCZ R-18980; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Utcubamba | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Perico | MCZ R-18961; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Santa Teresa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Loreto | Sucusari | iNaturalist; photo examined |