Published June 7, 2022. Updated December 12, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus atriventris)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Alopoglossidae | Alopoglossus atriventris

English common names: Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard, Blackbelly Shade-Lizard, Black-bellied Forest-Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija sombría ventrinegra, lagartija sombría de vientre quillado.

Recognition: ♂♂ 14.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.5 cm. ♀♀ 13.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.2 cm..1,2 The Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus buckleyi) is a small, brownish lizard that can be distinguished from other Amazonian leaf-litter lizards by having strongly keeled dorsal scales arranged in oblique rows on the dorsum and arms3,4 and by the absence of occipital and postparietal scales.5 Within its distribution area, A. atriventris is often confused with A. buckleyi, A. carinicaudatus, and A. copii, from which it differs by having granular neck scales and keeled ventral scales.2,6–8 Alopoglossus buckleyi differs from Loxopholis parietalis by its larger size, lack of red ventral coloration in adult males, and parietal scales not forming a semicircle.6,9 Adult males of the Blackbelly Shade-Lizard can be differentiated from adult females by having a black belly (light cream in females) in which each keel is white, giving a dashed line effect.1,8,9

Figure 1: Individuals of Alopoglossus atriventris from Gareno, Napo province () and Yasuní Scientific Station, Orellana province (), Ecuador.

Natural history: Alopoglossus atriventris is a frequently encounteredRecorded weekly in densities below five individuals per locality. lizard in old-growth to moderately disturbed lowland rainforests, logged forests, swamps,10 and shaded plantations in Ecuador.6,11 This species appears to prefer terra-firme forests rather than seasonally flooded forests.12 Keel-bellied Shade-Lizards are active during sunny or cloudy days, especially between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm, with a peak of activity in the late morning.12,13 They usually move among the leaf-litter at the base of large stumps and buttress roots, but they also climb tree trunks less than a meter high.9,12 Although these lizards spend most of their life in the shade,10 they bask occasionally in the sunlight that filters through the rainforest canopy.12 At night, they hide under leaf-litter or under logs.14 The diet in this species is primarily (up to 94.3% based on volume) composed of small (around 6.6 mm long) spiders, grasshoppers, crickets, and cockroaches.9,12,13 The diet includes at least 12 additional prey items ranging from springtails and mites to pseudoscorpions, millipedes, and mollusks.12,13 Predators of A. atriventris include the vipers Bothrocophias hyoprora, Bothrops brazili, and B. taeniatus.10 Parasites include tapeworms and nematodes.15 The primary defense strategy of these jittery lizards is their camouflage and fleeing into the leaf-litter when disturbed; they may also shed the tail or bite if captured.14 The clutch size in this species consists of two eggs.9,10

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..11,16,17 Alopoglossus atriventris is included in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, presence in protected areas, and presumed large stable populations.11 In the Brazilian Amazonia, about 48% of the occurrence area of A. atriventris is inside protected areas and about 98% of its original forest habitat is still standing.18 The status in Ecuador is similar. Based on the most recent maps of vegetation cover of the Amazon basin,19 the majority (~90%) of the species’ habitat in Ecuador remains forested. Thus, A. atriventris is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

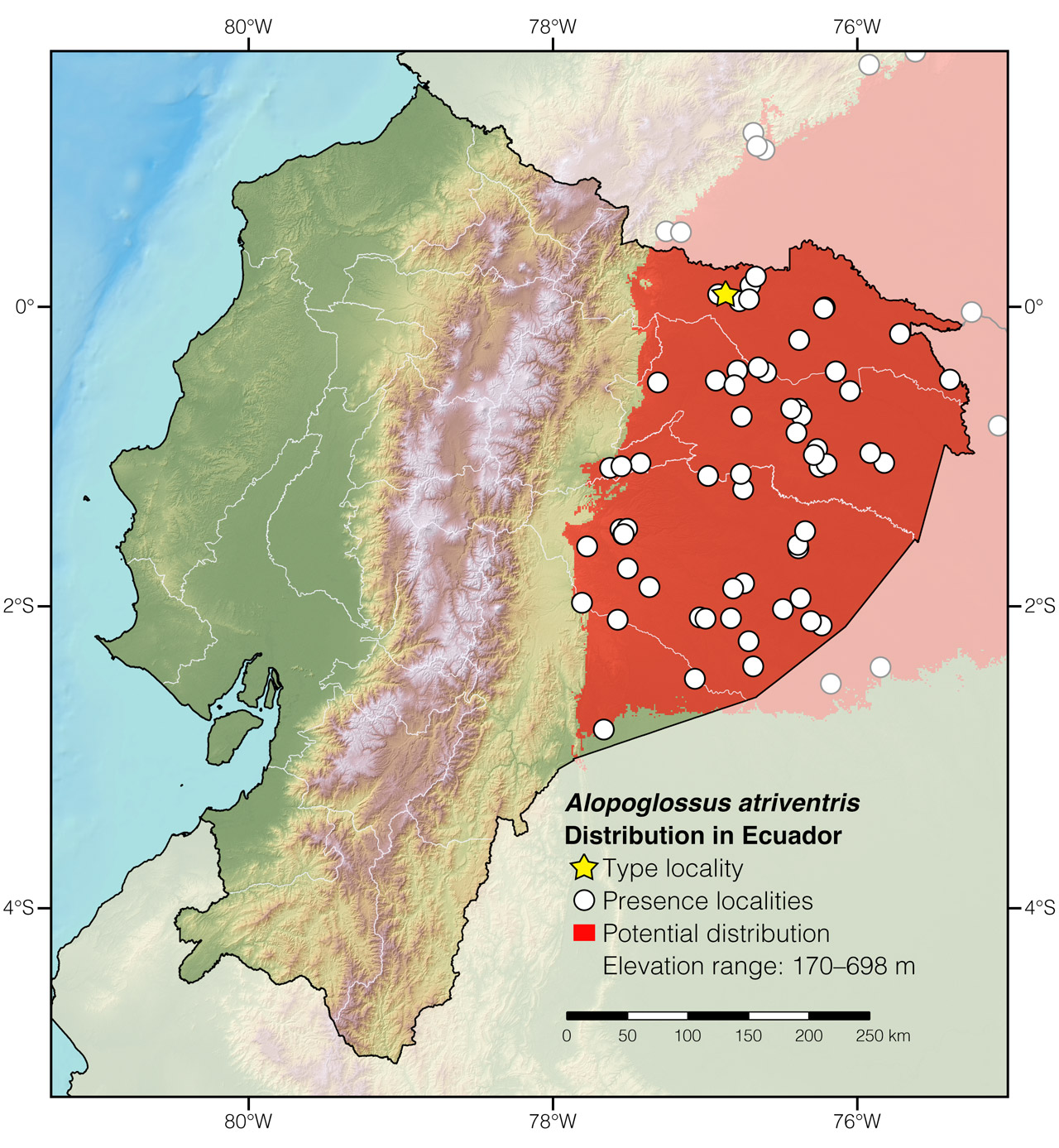

Distribution: Alopoglossus atriventris is native to an area of approximately 935,081 km2 in the Amazon basin of Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.18

Figure 2: Distribution of Alopoglossus atriventris in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Lago Agrio. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Alopoglossus, which is derived from the Greek words alopekia (=bare) and glossa (=tongue),20 refers to the tongue of lizards of this genus, which lacks scale-like papillae.3,21 The specific epithet atriventris, which is derived from the Latin words atra (meaning “black”) and ventris (meaning “belly”), refers to the ventral coloration of the adult males in this species.1

See it in the wild: Even though they are not the most common leaf-litter lizard wherever they occur, Keel-bellied Shade-Lizards can be seen with relative ease in forested areas throughout the species’ area of distribution in Ecuador. These shy reptiles may be spotted during the daytime by scanning the leaf-litter in areas of filtered sunlight reaching the forest floor. At night, they may be located by searching under leaf-litter and logs. In Ecuador, some of the best places to observe Keel-bellied Shade-Lizards are Yasuní Scientific Station and forest trails around Laguna Grande in Cuyabeno Reserve.

Special thanks to Kurt A Radamaker and S. King for symbolically adopting the Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Vieira J (2022) Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus atriventris). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/KFJT2146

Literature cited:

- Duellman WE (1973) Descriptions of new lizards from the upper Amazon basin. Herpetologica 29: 228–231.

- Köhler G, Hans-Helmut D, Veselý M (2012) A contribution to the knowledge of the lizard genus Alopoglossus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae). Herpetological Monographs 26: 173–188. DOI: 10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-10-00011.1

- Harris DM (1994) Review of the teiid lizard genus Ptychoglossus. Herpetological Monographs 8: 226–275. DOI: 10.2307/1467082

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Choueri E, Lobos S, Venegas P, Torres-Carvajal O, Werneck F (2020) Eight in one: morphological and molecular analyses reveal cryptic diversity in Amazonian alopoglossid lizards (Squamata: Gymnophthalmoidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 190: 227–270. DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz155

- Castro Herrera F, Ayala SC (1988) Saurios de Colombia. Unpublished, Bogotá, 692 pp.

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Camper JD, Torres-Carvajal O, Ron SR, Nilsson J, Arteaga A, Knowles TW, Arbogast BS (2021) Amphibians and reptiles of Wildsumaco Wildlife Sanctuary, Napo Province, Ecuador. Check List 17: 729–751.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Vitt LJ, De la Torre S (1996) A research guide to the lizards of Cuyabeno. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, 165 pp.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Calderón M, Perez P, Avila-Pires TCS, Aparicio J, Moravec J (2019) Alopoglossus atriventris. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T44578076A44578081.en

- Vitt LJ, Ávila-Pires TCS, Espósito MC, Sartorius SS, Zani PA (2007) Ecology of Alopoglossus angulatus and A. atriventris (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae) in western Amazonia. Phyllomedusa 6: 11–21. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v6i1p11-21

- Vitt LJ, Zani PA (1996) Organization of a taxonomically diverse lizard assemblage in Amazonian Ecuador. Canadian Journal of Zoology 74: 1313–1335.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Goldberg SR, Bursey C, Vitt LJ (2007) Parasite communities of two lizard species, Alopoglossus angulatus and Alopoglossus atriventris, from Brazil and Ecuador. Herpetological Journal 17: 269–272.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Amaral S (2016) Diversity, distribution, and conservation of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) in the Brazilian Amazonia. Neotropical Biodiversity 2: 195–421. DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2016.1236769

- MapBiomas Amazonía (2022) Mapeo anual de cobertura y uso del suelo de la Amazonía. Available from: www.amazonia.mapbiomas.org

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Alopoglossus atriventris in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bloque 31 | Libro PetroAmazonas |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Aguacate | Gutiérrez-Lamus et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Online multimedia |

| Colombia | Cauca | Serranía de los Churumbelos | Hernández-Morales et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mocoa | Hernández-Morales et al. 2020 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mocoa, 10 km S of | Duellman 1973 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Entre los Ríos Churuyaco y Rumiyaco | IAvH-R-4882 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Jardín de Sucumbios, 3 km NE of | ICN 8044 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Parque Nacional Natural La Paya | IAvH-R-5784 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Los Tayos | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mirador de la Virgen | Carvajal-Campos & Pazmiño-Otamendi 2020 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Shuin Mamus | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Liana Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo Obe | Carvajal-Campos & Pazmiño-Otamendi 2020 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo Shiripuno | Photo by Néstor Acosta |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Indillama Sur | Field notes of Ana María Velasco |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Parcela botánica | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Amo 2 | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Iro | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo petrolero Daimi I | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Primavera | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Puerto Yuturi | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Rio Yasuní | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Saladero Río Tiputini | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 107 | Photo by Morley Read |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 72 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuni Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yuca Sur | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bataburo Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento K10 | Photo by Jorge Valencia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento K4 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campo Villano | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chichirota | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Kurintza | Photo by Diego Paucar |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Destacamento Militar Shiona | Avila-Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Huito Molino | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kurintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Lorocachi | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Avila-Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Morete | USNM 163439 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Nuevo Golondrina | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Paracachi | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pavacachi | Photo by Graham Bailey |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Garza 1 | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Petrolero Misión | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Conambo | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Huiyayacu | Hernández-Morales et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pastaza | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | UNOCAL Base Camp | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE Cuyabeno | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Güeppicillo | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lagartococha | Usma et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio* | Duellman 1973 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande | Torres-Carvajal & Lobos 2014 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | KU 183506 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Elena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Territorio Cofán Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Tigre | Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Yuvineto | MNHN 1978.2343; collection database |

| Perú | Loreto | Shiviyacu | Köhler et al. 2012 |