Published April 19, 2023. Updated December 12, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Keel-tailed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus carinicaudatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Alopoglossidae | Alopoglossus carinicaudatus

English common name: Keel-tailed Shade-Lizard.

Spanish common name: Lagartija sombría de cola estriada.

Recognition: ♂♂ 13.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.0 cm. ♀♀ 14.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.2 cm..1,2 Alopoglossus carinicaudatus can be distinguished from other Amazonian leaf-litter lizards by having strongly keeled dorsal and ventral scales3 and by lacking occipital and postparietal scales.4 Alopoglossus carinicaudatus differs from A. atriventris, A. buckleyi, and A. copii by having the sides of the neck covered in keeled scales similar in size to the dorsals (granular scales in the other species) (Fig. 1).2–5 Loxopholis parietalis can be differentiated from A. carinicaudatus by its smaller size, red belly in adult males, and posterior parietal scales forming a semicircle.6 Adult males of A. carinicaudatus differ from females by having a clear longitudinal line along the back.5

Figure 1: Adult male of Alopoglossus carinicaudatus from Yasuní National Park, Orellana province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Alopoglossus carinicaudatus is a frequently encounteredRecorded weekly in densities below five individuals per locality. diurnal lizard that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed lowland rainforests, forest clearings, and plantations.5,7 The species occurs in higher densities near the water, such as in seasonally flooded forests and along streams and swampy areas, than in terra-firme forest.5,7–9 Keel-tailed Shade-Lizards are more active from late morning to mid-afternoon and during sunny days or days with thin cloud cover.8,9 These terrestrial lizards prefer to move among leaf-litter in shaded areas,5,6 but have also be seen basking on logs or climbing the base of tree trunks.6,10 When not active, individuals hide under logs or in leaf-litter.1,6 The diet in this species is primarily (up to 92.3% in volume) composed of roaches, grasshoppers, crickets, and spiders, but includes at least 15 other types of prey.8,9 When disturbed, these shy reptiles flee into the leaf-litter, escape among tree roots, or jump into water; if captured, they can shed the tail or bite.5,8 Clutch size in this species consists of two eggs that average 11.6 x 6.4 mm.6,8 These are laid under logs6 or in the forest floor where the light reaches the ground.5

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Alopoglossus carinicaudatus is a recently described species; therefore, its conservation status has not yet been formally evaluated by the IUCN. Here, it is proposed to be included in the Least Concern category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, presence in protected areas, and presumed large stable populations.3 Based on the most recent maps of vegetation cover of the Amazon basin,11 the majority (~92%) of the species’ habitat in Ecuador remains forested. Thus, A. carinicaudatus is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

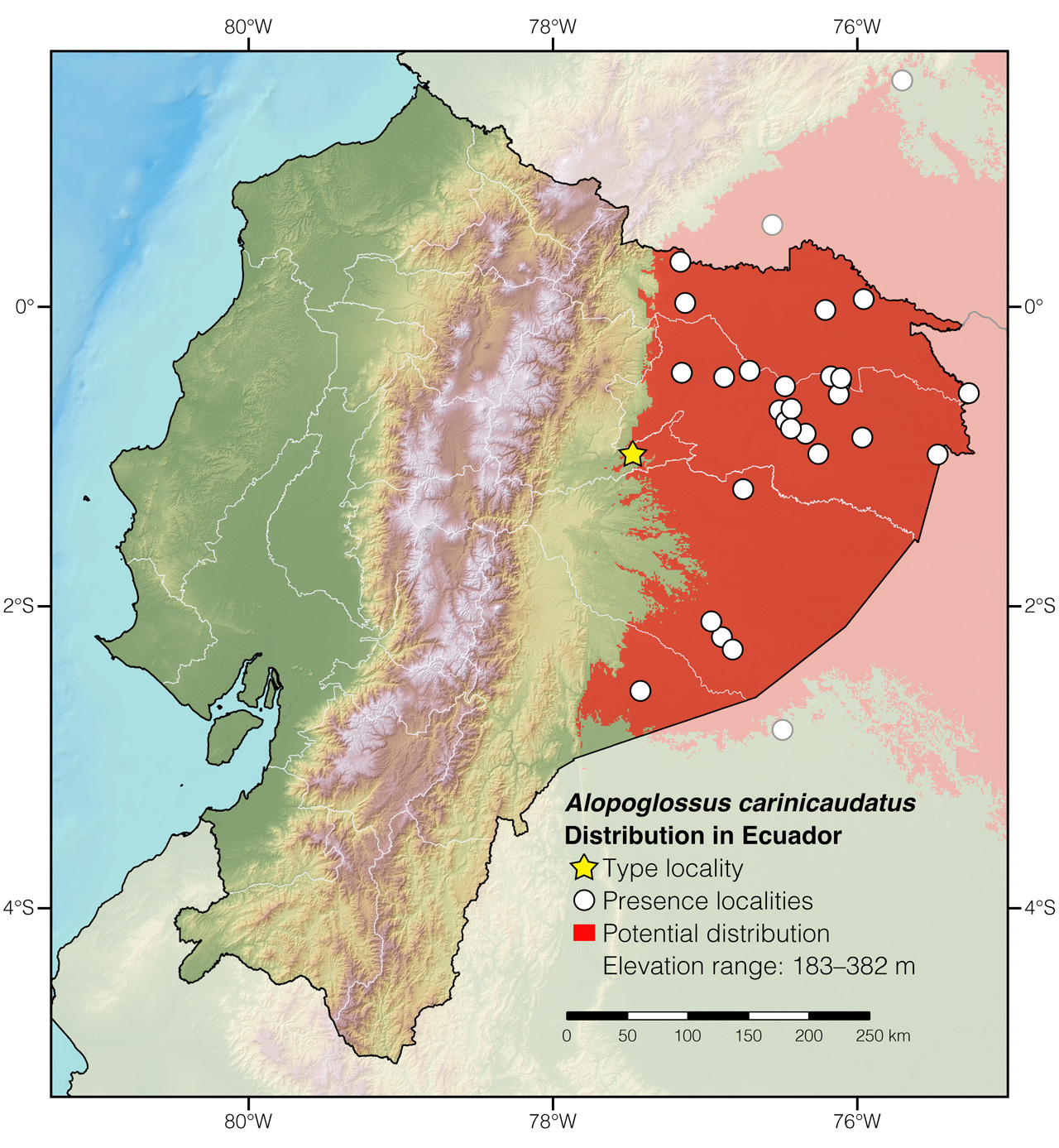

Distribution: Alopoglossus carinicaudatus is native to the upper Amazon basin of Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.3

Figure 2: Distribution of Alopoglossus carinicaudatus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Santa Rosa de Otas. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Alopoglossus is derived from the Greek words alopekia (=bare) and glossa (=tongue)12 and refers to the lack of scale-like papillae in the tongue of these lizards.13,14 The specific epithet carinicaudatus comes from the Latin words carina (=keel) and cauda (=tail),12 and refers to the keeled scales on the tail of this species.

See it in the wild: Keel-tailed Shade-Lizards can be seen with relative ease in Yasuní Scientific Station. They can be found along bodies of water or in the leaf-litter of flooded areas during daylight hours, particularly between 10:00 am and 3:00 pm. They can also be found at night under logs or in leaf-litter.

Acknowledgments: Thanks to Lina Parra for helping compile some of the information used in this account.

Special thanks to Carlos Cajas Bermeo for symbolically adopting the Keel-bellied Shade-Lizard and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Vieira J, Arteaga A (2023) Keel-tailed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus carinicaudatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/VFFO8174

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Köhler G, Hans-Helmut D, Veselý M (2012) A contribution to the knowledge of the lizard genus Alopoglossus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae). Herpetological Monographs 26: 173–188. DOI: 10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-10-00011.1

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Choueri E, Lobos S, Venegas P, Torres-Carvajal O, Werneck F (2020) Eight in one: morphological and molecular analyses reveal cryptic diversity in Amazonian alopoglossid lizards (Squamata: Gymnophthalmoidea). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 190: 227–270. DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlz155

- Castro Herrera F, Ayala SC (1988) Saurios de Colombia. Unpublished, Bogotá, 692 pp.

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Vitt LJ, De la Torre S (1996) A research guide to the lizards of Cuyabeno. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, 165 pp.

- Vitt LJ, Ávila-Pires TCS, Espósito MC, Sartorius SS, Zani PA (2007) Ecology of Alopoglossus angulatus and A. atriventris (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae) in western Amazonia. Phyllomedusa 6: 11–21. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v6i1p11-21

- Thomas O, Bird D, O’Donovan G (2020) The fish and herpetofauna of the Sani Reserve, Ecuador. Operation Wallacea, Lincolnshire, 262 pp.

- MapBiomas Amazonía (2022) Mapeo anual de cobertura y uso del suelo de la Amazonía. Available from: www.amazonia.mapbiomas.org.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Harris DM (1994) Review of the teiid lizard genus Ptychoglossus. Herpetological Monographs 8: 226–275. DOI: 10.2307/1467082

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Alopoglossus carinicaudatus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Macagual | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Finca Lupita | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Villa Ashuara | Avila-Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Francisco | UMMZ 84737; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Santa Rosa de Otas* | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Apaika | QCAZ 7242; Carvajal-Campos et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad El Edén | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Oasis | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Estrellayacu | QCAZ 1715; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Puente sobre el Río Beye | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní | UF 42503; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sitio A16 | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sitio A38 | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tambococha | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Boyopare | QCAZ 10612; Carvajal-Campos et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Parroquia Taracoa | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bataburo Lodge | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Killu Allpa | QCAZ 4832; Carvajal-Campos et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Santa Rosa | QCAZ 4858; Carvajal-Campos et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pica Montalvo–Chichirota | EPN 709; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Campo Vinita. vía Palma Roja-Pto El Carmen de Putumayo | QCAZ 7418; Carvajal-Campos et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comuna Duvuno | EPN 4974; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comuna Shuar Chari | EPN 4973; Köhler et al. 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha, 2.5 km S of | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Saladero de Dantas | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Perú | Loreto | Campo Andoas | Valqui Schult 2015 |

| Perú | Loreto | Redondococha | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Yubineto | MNHN 1978.2345; not examined |

| Perú | Loreto | Rosa Panduro | Riberio-Junior et al. 2019 |