Published December 14, 2020. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Brazil’s Lancehead (Bothrops brazili)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrops brazili

English common names: Brazil’s Lancehead, Velvety Lancehead.

Spanish common names: Equis mariposa (Ecuador); rabo de ratón (Colombia); jergón shushupe (Peru); Mapanare (Venezuela).

Recognition: ♂♂ 94.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 149.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. In Amazonian Ecuador, the Brazil’s Lancehead (Bothrops brazili) can be identified from other snakes by having the following combination of features: a triangular-shaped head with a snout that is not upturned, low keels (longitudinal ridges) on the dorsal scales, heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, a pinkish iris, and a contrasting dorsal pattern consisting of 16–20 dark brown triangular bands on the body plus several smaller blotches on the tail.1,2 The most similar viper that may be found living alongside B. brazili in Ecuador is B. atrox, which has a brownish iris, a broad and well-defined postocular stripe (thin and ill-defined in B. brazili), and faint, rather than contrasting, dorsal blotches. The toad-headed pitvipers (genus Bothrocophias) have an upturned snout and comparatively much smaller eyes. The Amazonian Bushmaster (Lachesis muta) differs from B. brazili by having prominent knoblike keels on the dorsal scales, which give the snake a “pineapple texture.”2,3

Figure 1: Adult male of Brazil’s Lancehead (Bothrops brazili) from Macuma, Morona Santiago province, Ecuador.

Natural history: UncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months.. Bothrops brazili is a terrestrial snake that inhabits evergreen lowland forests (rainforests), forest borders, and savannas.4 It also occurs in human-modified environments such as cassava plantations.2 The species generally requires more pristine habitats that the co-occurring Common Lancehead (B. atrox).5 Velvety Lanceheads are typically nocturnal, although juveniles have also been seen active during the daytime.2,6 They spend most of their time coiled on the forest floor, either among leaf-litter or at the base of trees and buttresses.6,7 They are also occasionally seen moving among shrubby vegetation or perched on leaves less than 1.5 m above the ground at night.8

Brazil’s Lanceheads are ambush predators.2 Their diet includes mostly (44.1%) mammals such as rodents and mouse opossums,2 but also frogs (23.5%), centipedes (23.5%), and lizards (14.7%) such as Alopoglossus atriventris.6–9 The diet of Bothrops brazili seems to shift from being based primarily on ectothermic (“cold-blooded”) prey as juveniles to based mostly on endothermic (“warm-blooded”) animals as adults.9 These vipers rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism.2 When threatened, some individuals flee or hide into the leaf-litter by means of undulatory body motions,10 others vigorously wiggle their tail against the substrate, and others just readily bite if attacked or harassed.6

Bothrops brazili is a venomous snake (LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 0.8–7.8 mg/kg)11,12 that injects an average of 3–4 ml of venom per bite.13 This species is responsible for 1–41.5% of snakebites in some areas of its range.14,15 In humans, its venom typically causes pain, swelling, intense bleeding, moderate defibrination (depletion of the blood’s coagulation factors), and severe necrosis (death of tissues and cells).11,12,16–18 In poorly managed or untreated cases, the venom can cause intracranial hemorrhage, permanent complications, and presumably also death.16 Fortunately, the antivenom available in Ecuador can, to a degree, neutralize the venom of B. brazili.11

What to do if you are bitten by a Brazil’s Lancehead?

|

Females of Bothrops brazili “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 9–30 young that measure 29.7–40 cm in total length.2,19 Under human care, individuals can live up to ~12 years,2 and probably much longer.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..20 Bothrops brazili is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed throughout the Amazon basin, a region that retains most of its original forest cover. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. In Ecuador, it is estimated that ~94.8% of the distribution range of B. brazili is still forested.21

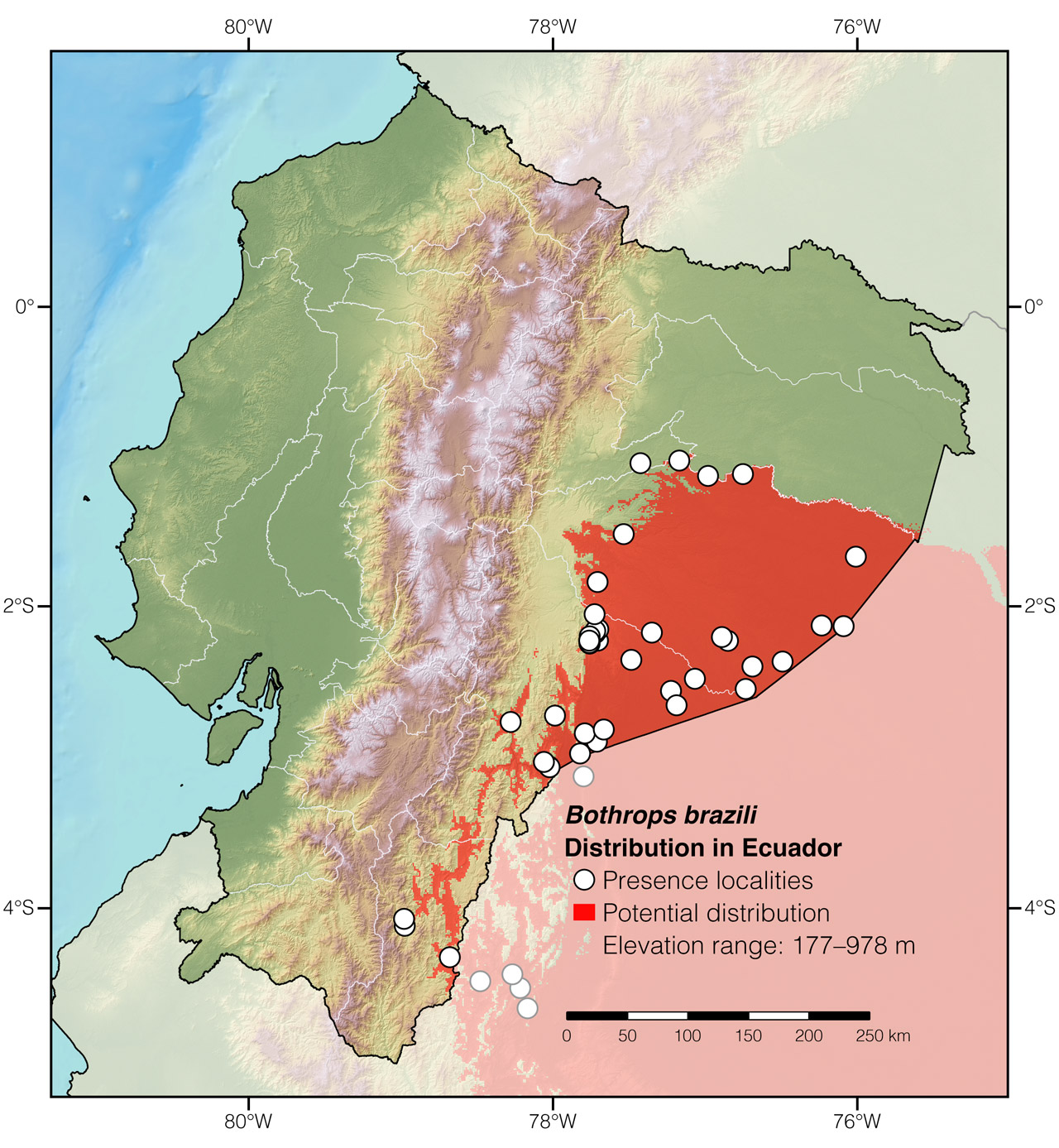

Distribution: Bothrops brazili is widespread throughout the southern portion of the Amazon rainforest, occurring in Brazil, Bolivia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Bothrops brazili in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Bothrops, which is derived from the Greek word bothros (meaning “pit”),23 refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils. The specific epithet brazili honors Brazilian physician and herpetologist Vital Brazil (1865–1950), founder and former director of the Butantan Institute in São Paulo.1

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Velvety Lanceheads are recorded rarely, usually no more than once every few months at any given locality. However, there are some areas, like around the town of Macuma and at Shiripuno lodge, where individuals are seen more frequently. The snakes may be located by walking along trails at night.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Darwin Núñez and José Manuel Falcón for providing locality data for Bothrops brazili. Thanks to María Elena Barragán (Vivarium Quito) for providing photographic access to live specimens under her care.

Special thanks to Tim Paine for symbolically adopting the Brazil’s Lancehead and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jorge ValenciabAffiliation: Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés (FHGO), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Brazil’s Lancehead (Bothrops brazili). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/WTYJ6190

Literature cited:

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Harvey MB, Aparicio J, Gonzales L (2009) Revision of the venomous snakes of Bolivia. II. The pitvipers (Serpentes: Viperidae). Annals of the Carnegie Museum 74: 1–37. DOI: 10.2992/0097-4463(2005)74[1:ROTVSO]2.0.CO;2

- França FGR, Mesquita DO, Colli GR (2006) A checklist of snakes from Amazonian savannas in Brazil, housed in the Coleção Herpetológica da Universidade de Brasília, with new distribution records. Occasional Papers of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History 17: 1–13.

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1975) Ofídios da Amazônia. VII—As serpentes peçonhentas do gênero Bothrops (jararacas) e Lachesis (surucucu) da região leste do Pará (Ophidia, Viperidae). Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 83: 1–42.

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Frank Pichardo, pers. comm.

- Martins M, Marques OAV, Sazima I (2002) Ecological and phylogenetic correlates of feeding habits in Neotropical pitvipers of the genus Bothrops. In: Schuett GW, Höggren M, Douglas ME, Greene HW (Eds) Biology of the vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, 307–328.

- Jorge Valencia, pers. comm.

- Laing GD, Yarleque A, Marcelo A, Rodríguez, E., Warrell DA, Theakston RDG (2004) Preclinical testing of three south American antivenoms against the venom of five medically-important Peruvian snake venoms. Toxicon 44: 103–106. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.03.020

- Muniz EG, Maria WS, Estevão-Costa MI, Buhrnheim P, Chávez-Olórtegui C (2000) Neutralizing potency of horse antibothropic Brazilian antivenom against Bothrops snake venoms from the Amazonian rain forest. Toxicon 38: 1859–1863. DOI: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00082-9

- Zavaleta A, Campos SM (1992) Estimación de la cantidad individual de veneno producida por serpientes venenosas peruanas. Revista Medica Herediana 3: 91–95.

- Smalligan R, Cole J, Brito N, Laing GD, Mertz BL, Manock S, Maudlin J, Quist B, Holland G, Nelson S, Lalloo DG, Rivadeneira G, Barragán ME, Dolley D, Eddleston M, Warrell DA, Theakston RDG (2004) Crotaline snake bite in the Ecuadorian Amazon: randomised double blind comparative trial of three South American polyspecific antivenoms. BMJ 329: 1129–1135. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.329.7475.1129

- Praba-Egge AD, Cone SW, Araim O, Freire I, Paida G, Escalante J, Carrera F, Chavez M, Merrell RC (2003) Snakebites in the rainforests of Ecuador. World Journal of Surgery 27: 234–240. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-002-6552-9

- Warrell DA (2004) Snakebites in Central and South America: epidemiology, clinical features, and clinical management. In: Campbell JA, Lamar WW (Eds) The Venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 709–761.

- Pantigoso C, Escobar E, Yarlequé A (2002) Action of the myotoxin from Bothrops brazili Hoge, 1953 snake venom (Ophidia: Viperidae). Revista Peruana de Biología 9: 74–83.

- Rojas E, Quesada L, Arce V, Lomonte B, Rojas G, Gutiérrez JM (2005) Neutralization of four Peruvian Bothrops sp. snake venoms by polivalent antivenoms produced in Perú and Costa Rica: preclinical assessment. Acta Tropica 93: 85–95. DOI: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2004.09.008

- Quetzal Dwyer, pers. comm.

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Bothrops brazili in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | 10 de Agosto | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Achuentz | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Amazonas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kenkuim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kiim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cerro Shaime | Photo by Freddy Velásquez |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chuwints | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | AMNH 107655 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Ladera oriental de Cutucú | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Makuma | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mamayak | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mutintz | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Paantim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Patuca | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Puerto Morona | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Santiago | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sawastian | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tiwintza | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Watsakentsa | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Yawints | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Photo by Etienne Littlefair |

| Ecuador | Orellana | 130 km de Tiguino | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Shiripuno Lodge |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Killu Allpa | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kurintza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Lorocachi | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mangourco (Manga Urco) | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mashient | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Tigre | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shuin Mamus | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Uyuimi | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Yuntzuntza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Bombuscaro entrance to PNP | Cisneros-Heredia 2004 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Limón | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Shaime | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Perú | Amazonas | Alto Yutupis | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Caterpiza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Kagka | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Kubaim | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Mouth of Kagka river | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Cenepa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Shiwan Entsa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Vicinity of Aintam | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pongo Chinim | FMNH 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Quebrada Yanayacu | Rengifo & Pérez 2013 |