Published October 15, 2020. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Amazonian Toadhead (Bothrocophias hyoprora)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrocophias hyoprora

English common names: Amazonian Toadhead, Amazonian Toad-headed Pitviper, Amazonian Hog-nosed Viper, Amazonian Hognose Viper.

Spanish common names: Nariz de puerco, hocico de puerco (Ecuador); sapa, equis sapa (Colombia); jergón pudridora, yatutu (Peru).

Recognition: ♂♂ 65.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 86 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. The Amazonian Toad-headed Pitviper (Botrocophias hyoprora) can be identified by having a triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, a stout body, non-prehensile tail, upturned snout, and tubercular keels on the dorsal scales.1,2 The dorsal color may be reddish brown, dark brown, reddish orange, yellowish, or gray, with 14–19 dark trapezoidal or rectangular dorsal blotches.1,3 Bothrocophias hyoprora can be distinguished from the similar B. microphthalmus by having a pattern of trapezoidal blotches rather than X-shaped markings, and by having entire subcaudal scales.1,3 Bothrops atrox and B. brazili can be separated from B. hyoprora by lacking an upturned snout.3

Figure 1: Individuals of Bothrocophias hyoprora from Gareno, Napo province, Ecuador (); Curaray medio, Pastaza province, Ecuador (); and Macuma, Morona Santiago province, Ecuador (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: UncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months.. Bothrocophias hyoprora is a cryptozoic (preferring moist, shaded microhabitats) snake of forested environments. It occurs mainly in old-growth to moderately disturbed terra-firme (not seasonally flooded) and partially flooded evergreen lowland forests but may as well be found in forest borders and human-modified areas such as crops.1–3 Amazonian Toad-headed Pitvipers inhabit areas having an annual mean temperature of ~20–27° C and a mean precipitation of 1659–4227 mm.4 Amazonian Toadheads are most active during the first hours after sunset,1,2 waiting in ambush, moving on the forest floor, and occasionally crossing roads and trails.1,5 During the day, individuals often stay quiet, hidden from sun exposure in leaf-litter, under trunks, among roots, or at the base of trees.1,2,5 There are records of individuals perched on vegetation up to 5 m above the ground.6

Amazonian Toadheads are ambush predators. When prey is nearby, they “bite and release,” subsequently following the scent trail of the envenomed animal and finally proceed to eat it.1 Their diet consists primarily (41.5%) on lizards (including Alopoglossus atriventris and Potamites ecpleopus), but also on small mammals like rodents and marsupials (25%), frogs such as Allobates femoralis and Hyloxalus yasuni (25%), and centipedes (8.3%).1,7,8–11 They also occasionally include snakes in their diet.12

Individuals of Bothrocophias hyoprora rely on camouflage as their primary defense mechanism.1 They are not aggressive, but calm and sluggish when confronted.3 When threatened, most individuals will try to flee or hide, while others will vigorously vibrate the tail against the substrate.1,7 Little is known about the predators of Amazonian Toadhead Pitvipers. The only recorded predator is the Slate-colored Hawk (Buteogallus schistaceus).1

Bothrocophias hyoprora is a venomous snake, but human envenomations caused by this species are infrequent, representing no more than 0.35–12.5% of the total number of snakebites at any given locality.13,14 Most reported envenomations have occurred in indigenous communities.15 The venom of B. hyoprora is necrotic, hemolytic, and cytotoxic.1,13,16 In humans, the venom causes intense pain, swelling, loss of consciousness, necrosis (death of tissues and cells), intense bleeding, and, in some cases, death.1,15

What to do if you are bitten by a Amazonian Toadhead?

|

Females of Bothrocophias hyoprora “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother) to 4–13 neonates that measure 14.8–19 cm in total length.1,2 One gravid female in Ecuador was found to contain 21 embryos.5 Under human care, one adult female lived for about eight years.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Bothrocophias hyoprora has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN. In Ecuador, the species is listed as Least Concern17 because it is widely distributed throughout the Amazon basin, an area that retains the majority of its original forest cover. It is estimated that 88.5% of the species’ area of distribution in Ecuador still holds rainforest habitat.18 Bothrocophias hyoprora is also listed in this category because it occurs in large protected areas (such as Cuyabeno Wildlife Reserve and Yasuní National Park). The most important threat to the long-term survival of populations of this pitviper species is forest destruction due to mining and the expansion of the agricultural frontier.19

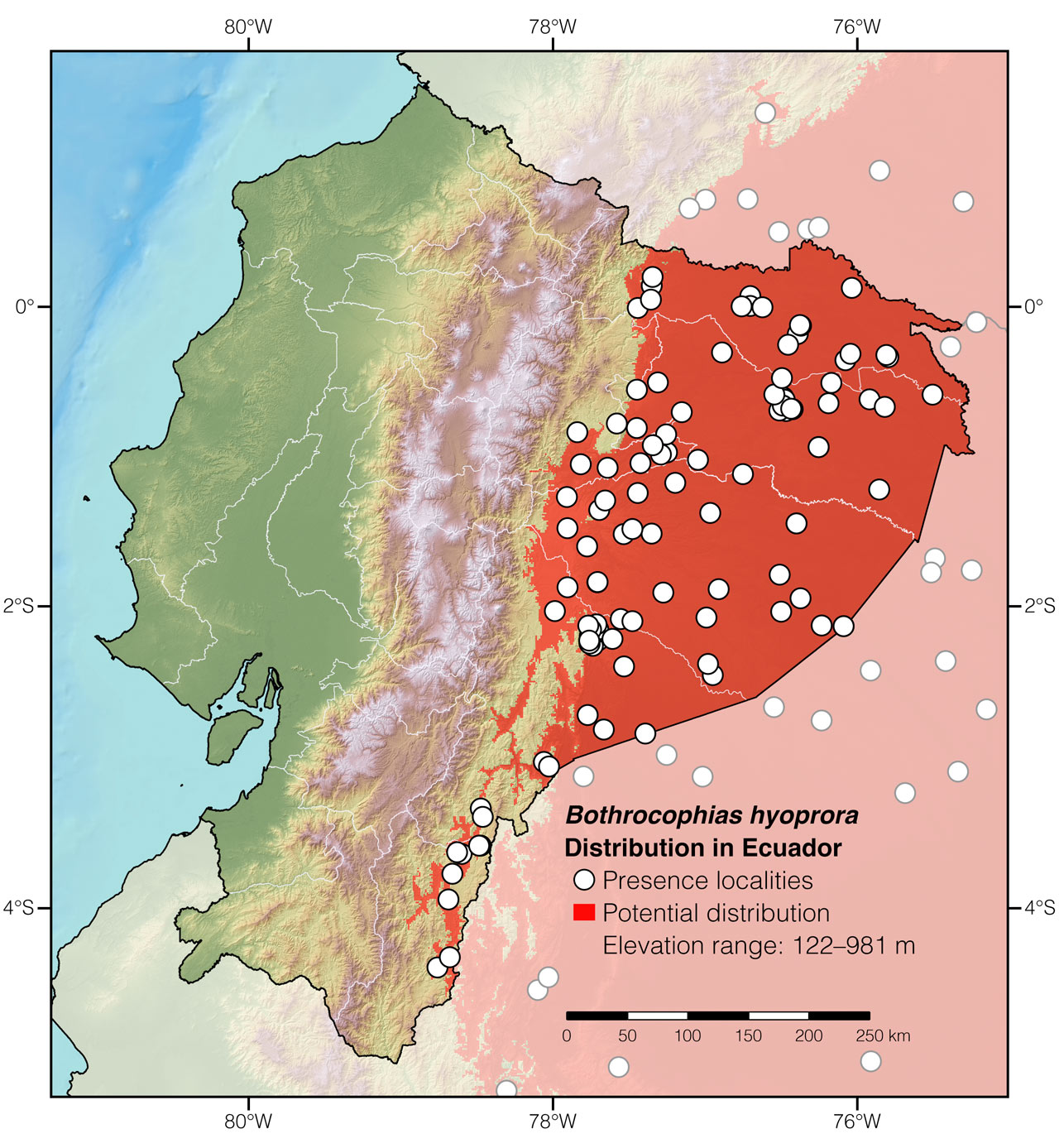

Distribution: Bothrocophias hyoprora is native to an estimated ~513,480 km2 area throughout the Amazon basin in Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, and Perú.20 In Ecuador, the species occurs at elevations between 122 and 981 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Bothrocophias hyoprora in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Bothrocophias, which is derived from the Greek words bothros (meaning “pit”) and kophias (meaning “snake”), refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils.3 The specific epithet hyoprora, which is derived from the Greek words hyos (meaning “hog”) and prora (meaning “snout”), refers to the prominent upturned snout.3

See it in the wild: Amazonian Toad-headed Pitvipers can be located with ~1–3% certainty in forested areas throughout the species distribution in Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find vipers of this species are Yasuní Scientific Station, Shiripuno Lodge, Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, and Tiputini Biodiversity Station. These vipers are most easily located by scanning the leaf-litter along trails in primary forest at night.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Darwin Núñez, Ernesto Arbeláez, Jorge Vaca, and María Elena Barragán for providing locality data and natural history information for Bothrocophias hyoprora. Thanks to Ernesto Arbeláez (Bioparque Amaru) and María Elena Barragán (Vivarium Quito) for providing photographic access to live specimens under their care.

Special thanks to Maurice Fakkert for symbolically adopting the Amazonian Toadhead and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Andrés F. Aponte-Gutiérrez,aAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.,bAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. Juan Acosta-Ortiz,cAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia. and Leonardo Niño-CárdenasdAffiliation: Laboratorio de Anfibios, Instituto de Ciencias Naturales, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Aponte-Gutiérrez A, Acosta-Ortiz J, Niño-Cárdenas L (2020) Amazonian Toadhead (Bothrocophias hyoprora). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/RICT3003

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Borja MO, Proaño D, Touzet JM (2006) Distribution and natural history of the Ecuadorian toad-headed pitvipers of the genus Bothrocophias. Herpetozoa 19: 17–26.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Vaca-Guerrero JE (2012) Biogeografía del género Bothrocophias (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae), mediante modelamientos de nicho ecológico. BSc Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, 116 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photographic record by Bryan Suson.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Martins M, Marques OAV, Sazima I (2002) Ecological and phylogenetic correlates of feeding habits in Neotropical pitvipers of the genus Bothrops. In: Schuett GW, Höggren M, Douglas ME, Greene HW (Eds) Biology of the vipers. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, 307–328.

- Niceforo M (1938) Las serpientes colombianas de hocico proboscidiforme, grupo Bothrops lansbergii-nasuta-hyoprora. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 2: 417–421.

- Santos JC, Cannatella DC (2011) Phenotypic integration emerges from aposematism and scale in poison frogs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108: 6175-6180. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1010952108

- Bernarde PS, Ferreira-Martins LS, Rodríguez-Oliveira J (2008) Bothrocophias hyoprora. Diet. Herpetological Review 39: 353.

- De Carvalho DT, de Fraga R, Eler ES, Kawashita-Ribeiro RA, Feldberg E, Vogt RC, De Carvalho MA, De Noronha JDC, Condrati LH, Bittencourt S (2013) Toad-headed pitviper Bothrocophias hyoprora (Amaral, 1935) (Serpentes, Viperidae): new records of geographic range in Brazil, hemipenial morphology, and chromosomal characterization. Herpetological Review 44: 410–414.

- Silva Haad J (1989) Las serpientes del genero Bothrops en la amazonia colombiana: aspectos biomedicos (epidemiologia, clinica y biologia del ofidismo). Acta Médica Colombiana 14: 148–165.

- Touzet JM (1986) Mordeduras de ofidios venenosos en la comunidad de los indígenas Siona-Secoya de San Pablo de Kantesyia y datos sobre la fauna de reptiles y anfibios locales. Publicaciones del Museo Ecuadoriano de Ciencias Naturales 7: 163–190.

- Warrell DA (2004) Snakebites in Central and South America: epidemiology, clinical features, and clinical management. In: Campbell JA, Lamar WW (Eds) The Venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 709–761.

- Bonilla C, Zavaleta A (1997) Estudio bioquímico del veneno de la serpiente Bothrops hyoprorus. Revista de Medicina Experimental 14: 18–32.

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Valencia JH, Barragán ME, Garzón K, Vargas A (2010) Reporte preliminar de mordedura de vipéridos en la provincia de Manabí, y notas sobre las áreas epidemiológicas con mayor concentración de serpientes venenosas. Gestión Ambiental 2: 9–13.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Bothrocophias hyoprora in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Bocana Canelos | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Los Ángeles | Sinchi Institute 2017 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Solano | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Colombia | Cauca | Churumbelos | MHNUC |

| Colombia | Cauca | Santa Rosa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | E Puerto Asís | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Near Río Patascoy | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Juanambu | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | RN La Isla Escondida | RN La Isla Escondida |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda Las Vegas | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda Peneya | Photo by Brayan Coral Jaramillo |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | 10 de Agosto | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | 24 de Mayo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | 4 km NE of Andush | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Amazonas | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kenkuim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kiim | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chuwints | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | E Puerto Morona | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | El Tiink | Photo by Germán Petsain |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Huamboya, Chiguaza | USNM 165315 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mutintz | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Paantim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Quebrada Yuwints | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Palora at 800 m | Photo by Jorge Brito |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Pedro | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Timias | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tiwintza | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tunants | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Wisui | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Yawints | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Near Huamaní | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pangayacu | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Puerto Napo | UIMNH 55926 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Suno | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | S of Chontapunta 1 | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | S of Chontapunta 2 | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yuralpa | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Chiruisla | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dicaro | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Edén | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Guiyero | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Joya de los Sachas | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | USNM 165313 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | N of Yasuní Scientific Station | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nenkepare | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF | Paulina Romero, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF–Tivacuno, km 8 1/2 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pompeya Sur–NPF | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Capirón | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Photo by Ross Maynard |

| Ecuador | Orellana | SE Sumaco | USNM 165311 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Photo by Bryan Suson |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sinchichicta | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Souther part of YNP | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur-Iro, km 38 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 28 | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 99 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Bobonaza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campo Oglán | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | USNM 165306 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | USNM 165302 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Curaray Medio | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Iwia (Achuar) | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kurintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | North of Kapawi Lodge | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Capahuari | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Copataza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Oglán | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Shionayacu | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Tigre | USNM 165318 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Santa Clara | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu–Montalvo | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Upstream Río Copataza | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Upstream Río Tigre | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Uyuimi | NCI |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano A | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Along río San Miguel | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Atenas | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Between Cascales and Campo Bermejo | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Campo Andes Petroleum | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Campo Bermejo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno, north of | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pitsorie-Setsacco | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Reserva Cofán-Dureno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Aguarico near Cuyabeno | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | Photo by Bryan Suson |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Elena | QCAZ 2743 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Secoya 32 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shirley A | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Zábalo | Photo by Juan Carlos Ríos |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Zancudococha | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Pangui | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Los Encuentros | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Maycu | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Namacuntza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Paquisha | This work |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Polvorín | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Shaime | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tundayme | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Caterpiza | MVZ 175374 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Puerto Pakuy | Lomonte et al. 2020 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Quebrada Kampankis | FMNH 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Aguas Negras | FMNH 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Charupa | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Güeppí | FMNH 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Lote 39 | Tomba 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Manseriche | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Morona | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | NW of Pavayacu | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Olaya–Tigre | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pampa Hermosa | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pongo Chinim | FMNH 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pozo al este de Andoas | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pozo al norte de Andoas | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pozo al sur del Río Tigre | Vaca Guerrero 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | S Arica | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | W Andoas | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Zona Reservada Güepi | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Loreto | Zona Reservada Pucacuro 1 | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Loreto | Zona Reservada Pucacuro 2 | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |