Published March 2, 2022. Updated August 18, 2025. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Cloud Forest Centipede-Snake (Tantilla fraseri)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Tantilla fraseri

English common names: Cloud Forest Centipede-Snake, Fraser’s Centipede Snake.

Spanish common names: Culebra ciempiés de bosque nublado, culebra ciempiés de Fraser.

Recognition: ♂♂ 44.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=34.0 cm. ♀♀ 31.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=25.3 cm..1,2 Tantilla fraseri may be recognized from other snakes in its area of distribution by having the following combination of features: smooth dorsal scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body, a round head similar in width to the neck, small eyes, no loreal scale, and a brownish dorsum with a pattern of thin black longitudinal lines, a cream postocular stripe, and a cream patch on the snout.3 The belly is yellow to orange-red.4 This species differs from T. equatoriana by having a cream snout patch and from T. miyatai by lacking a well-defined dark head cap. The presence of dorsal scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body distinguishes T. fraseri from other brownish co-occurring snakes such as Atractus dunni, Saphenophis boursieri, and Urotheca lateristriga.5 Juveniles of T. fraseri have a more contrasting head pattern that includes two cream spots on the nape.4,6

Figure 1: Individuals of Tantilla fraseri from Ecuador: Arlequín Reserve, Pichincha province (); San Jacinto, Carchi province ().

Natural history: Tantilla fraseri is a rarely seen snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed cloud forests, lower-montane forests, and areas containing a matrix of cattle pastures, crops, and rural houses.1 Cloud Forest Centipede-Snakes have been seen moving on leaf-litter or soil during the daytime. When not active, they hide under logs, beneath loose tree bark, or bury themselves in soft soil among roots and debris during the day or at night.1 Snakes of the genus Tantilla feed primarily on centipedes,7–9 but the specific dietary preferences of T. fraseri are not known. One individual was observed feeding on the egg of a lizard (Andinosaura oculata).10 Cloud Forest Centipede-Snakes rely on their secretive habits as a primary defense mechanism. When threatened, these calm but jittery snakes try to flee by digging into the soil; if captured, they may try to poke with their sharp tail-tip.1 Centipede snakes in general are opisthoglyphous, meaning they are venomous to their prey but harmless to humans. There is a record of an Urotheca lateristriga preying upon an individual of this species in Ecuador.1 Tantilla fraseri is likely an oviparous species, but the clutch size and nesting sites are not known.

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Tantilla fraseri is proposed to be included in this category following IUCN criteria,11 because the species has been recorded at 45 localities (including 16 protected areas; see Appendix 1) and it is distributed over an area that retains the majority (~68%) of its forest cover.12 Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. However, some populations are likely to be declining due to deforestation by logging and large-scale mining, especially in Imbabura province,13 where only four populations of the species are known. The fear of snakes is also a source of mortality to individuals of this species. People in rural regions tend to kill any snake, even those not dangerous to them.

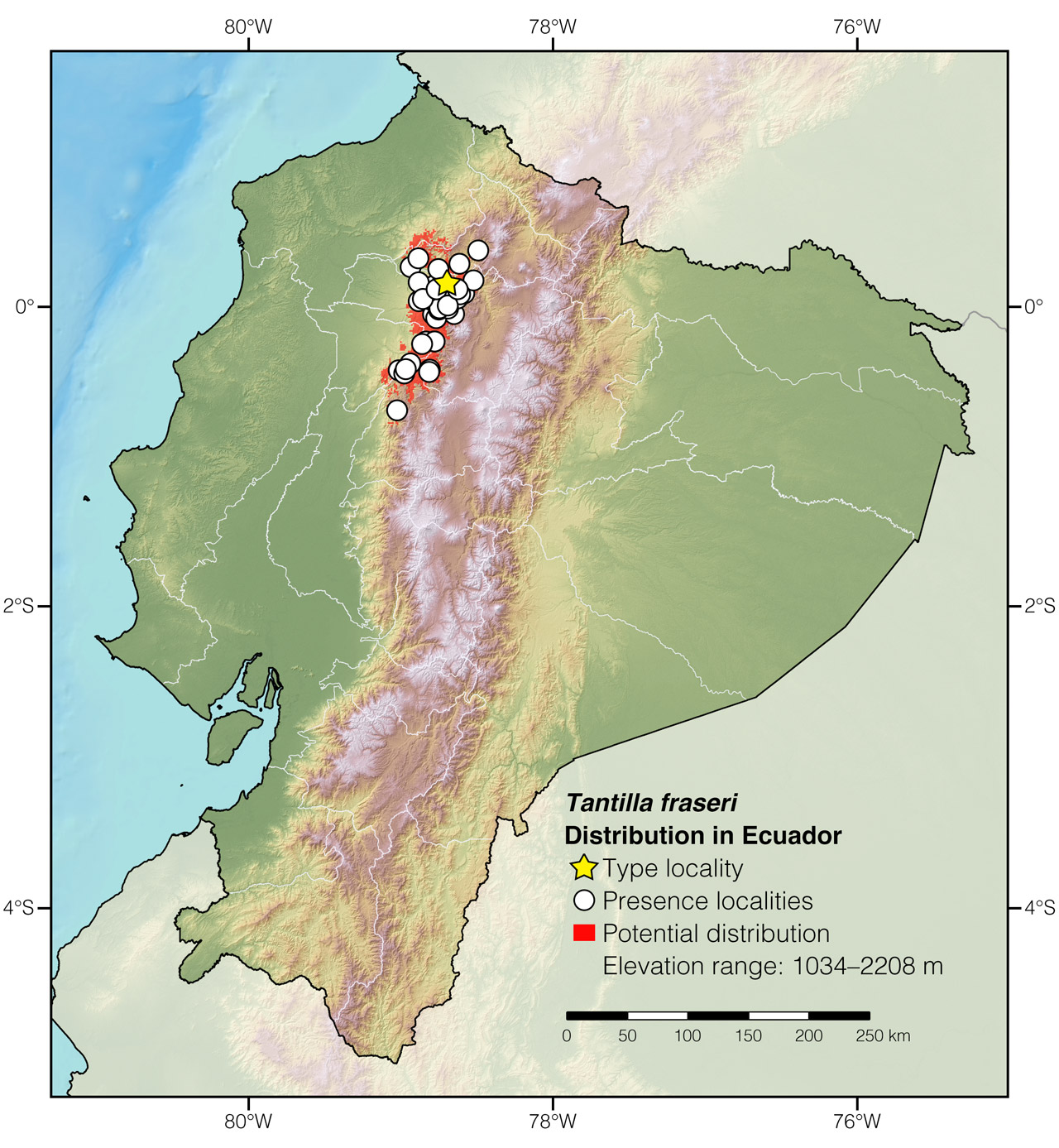

Distribution: Tantilla fraseri is endemic to an area of approximately 7,461 km2 along the Pacific slopes of the Andes of northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2). The presence of this species is also expected in neighboring Colombia.

Figure 2: Distribution of Tantilla fraseri in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the approximate type locality: western slopes of the Andes in the vicinity of Quito. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Tantilla, which is derived from the Latin word tantillus (=little),14 probably refers to the small body size of snakes of this genus. The specific epithet fraseri honors Louis Fraser, a British zoologist and naturalist who collected the holotype.

See it in the wild: With the exception of a few localities, Cloud Forest Centipede-Snakes are found no more than once every few months at any given area. They are usually found only by chance. The locality having the greatest number of observations is Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve, where, apparently, Tantilla fraseri is the most common snake species.4 It appears the best way to find Cloud Forest Centipede-Snakes is to slowly walk along trails through areas of well-preserved forest. Another option is to flip surface objects in clearing besides these areas during the daytime.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Phillip Hong-Barco for finding one of the individuals of Tantilla fraseri photographed in this account. This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2025) Cloud Forest Centipede-Snake (Tantilla fraseri). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/SMTS1944

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Greenbaum E, Carr JL, Almendáriz A (2004) Taxonomic status of Tantilla equatoriana Wilson and Mena 1980 (Serpentes: Colubridae). The Southwestern Naturalist 49: 457–464.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Tipantiza-Tuguminago L, Pulluquitín F, Barragán-Paladines ME, Noboa G (2017) Serpientes del Distrito Metropolitano Quito (DMQ), Ecuador, con comentarios sobre su rango geográfico y altitudinal y conservación. Avances en Ciencias e Ingeniería 9: 17–60. DOI: 10.18272/aci.v9i15.305

- Savit AZ (2006) Reptiles of the Santa Lucía Cloud Forest, Ecuador. Iguana 13: 94–103.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Yánez-Muñoz M, Meza-Ramos P, Ramírez S, Reyes-Puig J, Oyagata L (2009) Anfibios y reptiles del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito (DMQ). In: Yánez-Muñoz MH, Moreno-Cárdenas PA, Mena-Valenzuela P (Eds) Guía de campo de los pequeños vertebrados del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito (DMQ). Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales (MECN), Quito, 9–52.

- Acosta Vásconez AN (2014) Diversidad y composición de la comunidad de reptiles del Bosque Protector Puyango. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 157 pp.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Peters WCH (1863) Über einige neue oder weniger bekannte Schlangenarten des zoologischen Museums zu Berlin. Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1863: 272–289.

- Maddock ST, Smith EF, Peck MR, Morales JN (2011) Tantilla melanocephala (Black-headed Snake). Diet. Herpetological Review 42: 620.

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, Kohn S, Gavilanes G, Lynch RL, Hamilton PS, Maynard RJ (2019) A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Chocó-Andean Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ 7: e6400. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6400

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Tantilla fraseri in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Alto Gualpi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chical | Photo by María Elena Barragán |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Chical–Gualpi road | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Río Manduriacu Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Carchi | San Jacinto | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Below Sigchos | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Integral Otonga | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Palo Quemado | MHNG 2412.062; collection database |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Recinto Galápagos | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Bosque Protector Paso Alto | Mecham & Cueva 2009 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | El Palmal | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | El Refugio de Intag | Photo by Peter Joost |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Manduriacu Reserve | Jowers et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Área de amortiguamiento de la Reserva Pulhulahua | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Below Pacto | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Cambugán | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Chiriboga | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Chontal Alto | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Guarumos | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Kumbha Mela Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | La Esperanza, 10 km NE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Las Tolas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Maquipucuna Reserve | López et al. 1998 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Lodge | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Milpe Bird Sanctuary | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Garden | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Loma Bird Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Montecristi | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegal | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegalito | Photo by Andrew Cecil |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pacha Quindi Nature Refuge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Arlequín | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Las Gralarias | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Un Poco de Chocó | Photo by Andreas Kay |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Yunguilla | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Río Piripe | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | San Jorge de Tandayapa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | San Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi | MHNG 2398.039; collection database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi, 2 km S of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Bosque Protector Río Guajalito | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Estación Experimental La Favorita | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Las Palmeras | MHNG 2249.036; collection database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Miligali | Boulenger 1883 |