Published March 8, 2022. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Ecuadorian Centipede-Snake (Tantilla equatoriana)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Tantilla equatoriana

English common name: Ecuadorian Centipede-Snake.

Spanish common name: Culebra ciempiés ecuatoriana.

Recognition: ♂♂ 43.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=31.5 cm..1Tantilla equatoriana may be recognized from other snakes in its area of distribution by having the following combination of features: smooth dorsal scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body, a round head similar in width to the neck, small eyes, no loreal scale, and a brownish dorsum with a pattern of thin black longitudinal lines (Fig. 1).2 The belly is immaculate white and the head is brown with a long cream postocular stripe but no contrasting blackish head cap.2 Tantilla fraseri and T. miyatai are similar to T. equatoriana, but the first has a well-defined blackish head cap (indistinct in T. equatoriana) and the second has a broad cream snout patch (absent or reduced in T. equatoriana).3 The presence of dorsal scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body distinguishes T. equatoriana from other brownish co-occurring snakes such as Atractus iridescens, Coniophanes fissidens, and Urotheca lateristriga.4

Figure 1: Individuals ofTantilla equatoriana: Morromico Lodge, Chocó department, Colombia (); Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador ().

Natural history:Tantilla equatoriana is a rarely seen semi-fossorial snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen lowland forests as well as disturbed areas such as pastures and plantations.5 Ecuadorian Centipede-Snakes have been seen moving on soil and leaf-litter during the daytime or at night.5 Snakes of the genusTantilla in general feed primarily on centipedes,6–8 but the specific dietary preferences of T. equatoriana are not known. Ecuadorian Centipede-Snakes rely on their secretive habits as a primary defense mechanism. When threatened, these calm but jittery snakes try to flee by digging into the soil or disappearing into the leaf-litter; if captured, they may try to poke with their sharp tail-tip.5 Centipede snakes are opisthoglyphous, meaning they have enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla and are venomous to arthropods but not to humans. There is a record of an Erythrolamprus mimus preying upon an individual of this species during the daytime.5Tantilla equatoriana is likely an oviparous species, but the clutch size and nesting sites are not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..Tantilla equatoriana has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Here, the species is proposed to be included in the LC category given its wide distribution over a region (the Colombian Pacific coast) that has not been heavily affected by deforestation. Therefore, T. equatoriana is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. However, in the Pacific lowlands of northwestern Ecuador, much (~53%)9 of the species’ habitat has been lost due to deforestation caused by rural-urban development and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. For this reason, T. equatoriana may qualify for a threatened category in the future if its habitat continues to be destroyed.

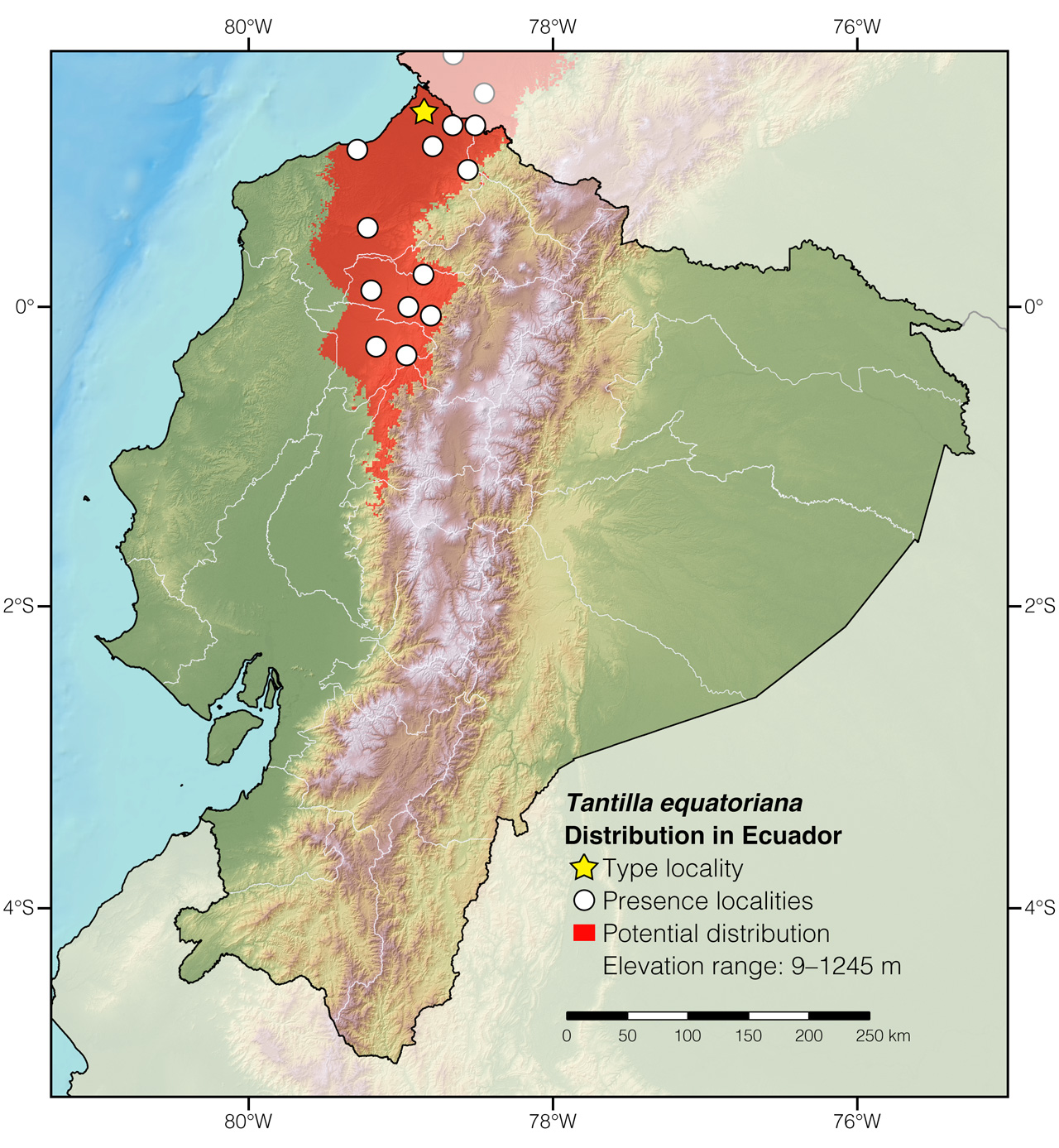

Distribution:Tantilla equatoriana occurs in the Chocoan lowlands and adjacent Andean foothills from western Colombia to Cotopaxi province in northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution ofTantilla equatoriana in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: San Lorenzo, Esmeraldas province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic nameTantilla, which is derived from the Latin word tantillus (=little),10 is probably a reference to the small body size of snakes of this genus. The specific epithet equatoriana refers to the Equator and the country of origin.2

See it in the wild: Ecuadorian Centipede-Snakes cannot be expected to be seen reliably using standard methods of field herpetology. Individuals of this elusive snake are found no more than once every few months at any given area and usually only by chance. Apparently, the only locality where the species has been recorded more than once is the town of San Lorenzo, Esmeraldas province. The majority of individuals have been found by walking along forest trails during the daytime.

Notes: This account follows Wilson and Mena (1980)2 and Wilson (1999)11 in recognizingTantilla equatoriana as a valid species distinct from T. melanocephala, a view contrary to Greenbaum et al. (2004).1 An unpublished12 species delimitation analysis based on DNA sequences confirms the original arrangement, a view that is shared here based also on the differences in head pattern between the two species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Ecuadorian Centipede-Snake (Tantilla equatoriana). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/BUZN7430

Literature cited:

- Greenbaum E, Carr JL, Almendáriz A (2004) Taxonomic status ofTantilla equatoriana Wilson and Mena 1980 (Serpentes: Colubridae). The Southwestern Naturalist 49: 457–464.

- Wilson LD, Mena CE (1980) Systematics of the melanocephala group of the colubrid snake genusTantilla. Memoirs of the San Diego Society of Natural History 11: 5–58.

- Wilson LD (1987) A résumé of the Colubrid snakes of the genusTantilla of South America. Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology 68: 1–35.

- MECN (2010) Serie herpetofauna del Ecuador: El Chocó esmeraldeño. Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales, Quito, 232 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Acosta Vásconez AN (2014) Diversidad y composición de la comunidad de reptiles del Bosque Protector Puyango. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 157 pp.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Peters WCH (1863) Über einige neue oder weniger bekannte Schlangenarten des zoologischen Museums zu Berlin. Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1863: 272–289.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Wilson LD (1999) Checklist and key to the species of the genusTantilla (Serpentes: Colubridae), with some commentary on distribution. Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service 122: 1–34. DOI: 10.5479/si.23317515.122.1

- Arteaga A (unpublished).

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map ofTantilla equatoriana in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | La Guayacana | MCZ 150222 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Río Rosario | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Tobar Donoso | Samec & Samec 1988 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Lita, 16 km W of | MHNG 2521.082 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Mayronga | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Javier | UIMNH 55725 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo* | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tulubí, 10 km E of | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | El Chalpi-Saguangal | Valencia et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hostería Selva Virgen | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Kapari Lodge | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Ruta al Cinto | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Otongachi Reserve | Wilson & Mata-Silva 2015 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Santo Domingo de los Colorados | Greenbaum et al. 2004 |