Published March 18, 2022. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Black-headed Centipede-Snake (Tantilla melanocephala)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Tantilla melanocephala

English common name: Black-headed Centipede-Snake.

Spanish common name: Culebra ciempiés cabecinegra.

Recognition: ♂♂ 43.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=30.9 cm. ♀♀ 39.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=31.7 cm..1–3Tantilla melanocephala may be recognized from other snakes in its area of distribution by having the following combination of features: smooth scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body, a round head similar in width to the neck, small eyes, no loreal scale, and a brownish dorsum with a black head cap and a pattern of thin black longitudinal lines (Fig. 1).2–7 The presence of straight lines and no dorsal spots distinguishes T. melanocephala from other brownish co-occurring snakes such as Taniophallus brevirostris and Atractus gaigeae.8

Figure 1: Individuals ofTantilla melanocephala: Santander department, Colombia (); Cotundo, Napo province, Ecuador (); Morromico, Chocó department, Colombia ().

Natural history:Tantilla melanocephala is an uncommon species in Ecuador,9 but is common in some areas of Colombia10 and Brazil.11 This is a semi-fossorial snake that, in Ecuador, occurs in the evergreen forest ecosystem, but elsewhere in South America also occurs in savannas and seasonally dry forests.12 This species is present in pristine habitats7,9 as well as in disturbed areas such as pastures,13 cultivated fields,2,10 rural gardens,9,14 and houses.14 Black-headed Centipede-Snakes have been seen moving on soil and leaf-litter1 or crossing roads3 during the daytime,6,7,9,15 at dusk,16 or at night.11 When not active, they bury themselves under soft soil2,9,14 or hide under rocks,17 surface debris, in termite mounds, or beneath logs.11 The diet of T. melanocephala is primarily composed of centipedes,3,11,13,18 but roaches6 are occasionally consumed.3 Centipede snakes are venomous to their prey but harmless to humans.11 The time between seizure of a centipede and the onset of pre-ingestion maneuvers is 2–7 minutes.11 Centipedes are always swallowed head first.11

Black-headed Centipede-Snakes rely on their secretive habits as a primary defense mechanism. When threatened, these calm but jittery snakes try to flee by digging into the soil or disappearing into the leaf-litter; if captured, they thrash the body vigorously3 and may shed portions of their tail.9,16 There are recorded instances of predation on members of this species, including by owls (Athene cunicularia),19 snakes (Bothrops atrox20 and Pseudoboa coronata7), and spiders.21,22 In seasonally dry areas, breeding coincides with the rainy season;11 but in the Amazon rainforest and in the Atlantic Forest, it seems to take place year-round.18,23 Gravid females containing 1–3 eggs have been found in the Amazon,2,3,7,24 and in the Cerrado and Atlantic Forest of Brazil.11 Clutch sizes of 2–3 eggs has been reported.16,25

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. 26Tantilla melanocephala is listed in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas, and presumed stable populations. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.26 Black-headed Centipede-Snakes persist in the urban-rural landscape and are likely to keep thriving under current scenarios of global warming.27 It has been hypothesized that these snakes are introduced in several islands in the Caribbean, including Grenada and Mustique, probably from Trinidad or northeastern South America, and likely via boat traffic.14,28 Some snakes may have arrived in construction materials, such as sand.28 There is information29–31 that suggests that this snake species suffers from traffic mortality and predation by house cats.

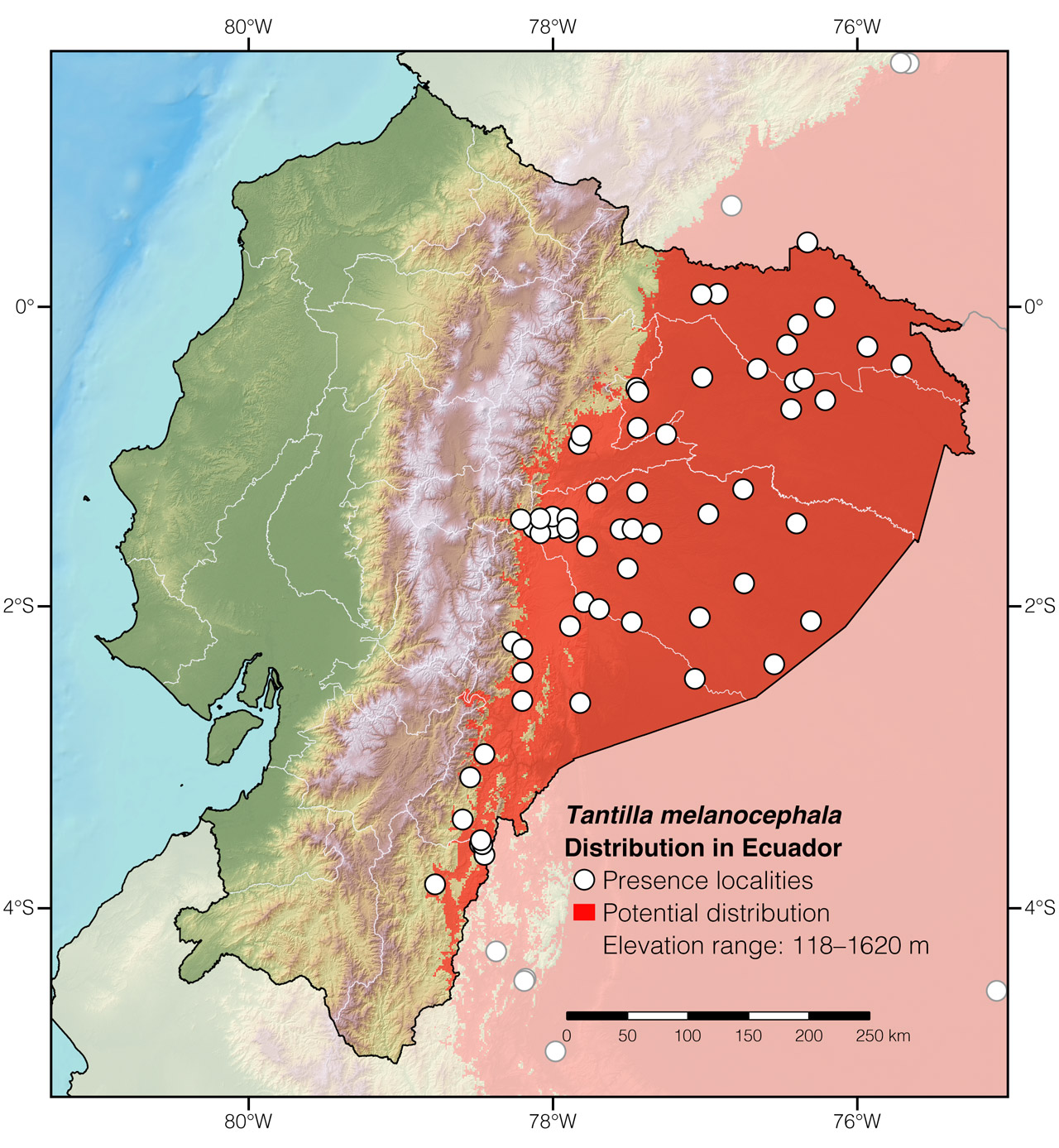

Distribution:Tantilla melanocephala is widely distributed throughout the lowlands and adjacent mountain foothills of Central America and South America, from Central Panamá, Venezuela, and the Lesser Antilles, to northeastern Argentina. The species has an estimated total range size of 2,946,399 km2 that encompasses eastern Mesoamerica, the northern Chocó rainforest, the Río Magdalena valley, the entire Amazon basin, the Cerrado, and the Atlantic Forest.12 In Ecuador, the species has been found only on the Amazonian region (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution ofTantilla melanocephala in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The nameTantilla is derived from the Latin word tantillus (=little)32 and probably refers to the small body size snakes of this genus. The specific epithet melanocephala comes from the Greek words melas (=black) and kephale (=head),32 referring to the black head cap.

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Black-headed Centipede-Snakes are found about once every few months, especially around the towns Archidona and Santa Cecilia, where individuals are typically spotted along forest trails during the daytime.

Notes: This account follows Wilson and Mena (1980)5 and Wilson (1999)33 in recognizingTantilla melanocephala and T. equatoriana as distinct species, a view contrary to Greenbaum et al. (2004).34Tantilla fraseri is also considered to be a valid taxon and not a synonym of T. melanocephala, following Peters (1960).35 An unpublished36 species delimitation analysis based on DNA sequences confirms these arrangements, a view that is shared here based also on the differences in head pattern between the species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,bAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Sebastián Di Doménico,dAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Black-headed Centipede-Snake (Tantilla melanocephala). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ECIK7982

Literature cited:

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Hoogmoed MS, Gruber U (1983) Spix and Wagler type specimens of reptiles and amphibian in the Natural History Museum in Munich (Germany) and Leiden (The Netherlands). Spixiana 9: 319–415.

- Wilson LD, Mena CE (1980) Systematics of the melanocephala group of the colubrid snake genusTantilla. Memoirs of the San Diego Society of Natural History 11: 5–58.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Whitworth A, Beirne C (2011) Reptiles of the Yachana Reserve. Global Vision International, Exeter, 130 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Lynch JD (2015) The role of plantations of the African palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in the conservation of snakes in Colombia. Caldasia 37: 169–182.

- Marques OAV, Puorto G (1998) Feeding, reproduction and growth in the crowned snakeTantilla melanocephala (Colubridae), from southeastern Brazil. Amphibia-Reptilia 19: 311–318. DOI: 10.1163/156853898X00214

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- Berg CS, Jeremiah A, Harrison B, Henderson RW (2009) New island records forTantilla melanocephala (Squamata: Colubridae) on the Grenada Bank. Applied Herpetology 6: 403–404. DOI: 10.1163/157075309X12531848433029

- Silva JL, Valdez J, Ojasti J (1985) Algunos aspectos de una comunidad de ofidios del norte de Venezuela. Biotropica 17: 112–125. DOI: 10.2307/2388503

- Marques R, Mebert K, Fonseca E, Rödder D, Solé M, Tinôco MS (2016) Composition and natural history notes of the coastal snake assemblage from Northern Bahia, Brazil. ZooKeys 611: 93–142. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.611.9529

- Quinn DP, McTaggart AL, Bellah TA, Bentz EJ, Chambers LG, Hedman HD, John R, Muñiz Pagan DN, Rivera Rodríguez MJ (2010) The reptiles of union Island, St. Vincent and the Grenadines. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 17: 223–234.

- Araujo de Oliveira F (2016) Variação geográfica na ecologia deTantilla melanocephala (Serpentes: Colubridae) em áreas de Caatinga e Floresta Atlântica no Nordeste na região Neotropical. MSc thesis, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, 51 pp.

- Granzinolli MAM, Motta-Junior JC (2003)Tantilla melanocephala (Black-headed Snake): predation. Herpetological Review 34: 156–157.

- Bisneto PF, Kaefer IL (2019) Reproductive and feeding biology of the common lancehead Bothrops atrox (Serpentes, Viperidae) from central and southwestern Brazilian Amazonia. Acta Amazonica 49: 105–113.

- Rocha CR, Motta PC, Portella AS, Saboya M, Brandão R (2017) Predation of the snakeTantilla melanocephala (Squamata: Colubridae) by the spider Latrodectus geometricus (Araneae: Theridiidae) in Central Brazil. Herpetology Notes 10: 647–650.

- De Sousa L, Manzanilla J, Cornejo-Escobar P (2007) Depredación sobre serpiente colúbrida por Latrodectus cf. geometricus Koch, 1841 (Araneae: Theridiidae). Ciencia 15: 410–412.

- Santos-Costa MC, Prudente ALC, Di-Bernardo M (2006) Reproductive biology ofTantilla melanocephala (Linnaeus, 1758) (Serpentes, Colubridae) from eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Journal of Herpetology 40: 553–556.

- Fitch H (1970) Reproductive cycles in lizards and snakes. Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, 247 pp.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Passos PGH, Powell R (2019)Tantilla melanocephala. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T203321A2763890.en

- Hurtado Morales MJ (2021) Vulnerabilidad e importancia de las serpientes en Colombia: escenarios de cambio climático, impactos antrópicos y servicios ecosistémicos. MSc thesis, Universidad de Los Andes, 131 pp.

- Daudin J, de Silva M (2007) An annotated checklist of the amphibians and terrestrial reptiles of the Grenadines with notes on their natural history and conservation. Applied Herpetology 4: 163–175. DOI: 10.1163/157075407780681329

- Photo by Daniel Mesa.

- Baltazar R, Burgos Gallardo F, Baldo JL (2013)Tantilla melanocephala (Linnaeus, 1758) - (Serpentes: Colubridae): primeros registros para la Provincia de Jujuy y confirmación de su presencia en el noroeste argentino. Cuadernos de Herpetología 27: 81–83.

- Photo by Saifudeen Muhammad.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Wilson LD (1999) Checklist and key to the species of the genusTantilla (Serpentes: Colubridae), with some commentary on distribution. Smithsonian Herpetological Information Service 122: 1–34. DOI: 10.5479/si.23317515.122.1

- Greenbaum E, Carr JL, Almendáriz A (2004) Taxonomic status ofTantilla equatoriana Wilson and Mena 1980 (Serpentes: Colubridae). The Southwestern Naturalist 49: 457–464.

- Peters JA (1960) The snakes of Ecuador; check list and key. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 122: 489–541.

- Arteaga et al. (unpublished).

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map ofTantilla melanocephala in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | MLS 1256 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Reserva La Avispa | UAM-R-0397 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda La Paz | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | 9 de Octubre | Tipantiza-Tuguminago et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Finca El Piura | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | General Plaza | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Kuchintsa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Miazal | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Normandía | AMNH 35896 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Upano | AMNH 28813 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Juan Bosco | Photo by Juan Carlos Sanchez |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Shuin Mamus | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona | MHNG 2441.014 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Photo by Scott Waters |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zoo el Arca | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Concepción | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | MHNG 2412.058 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | Photo by Thierry García |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Suno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bataburo Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bioparque Yanacocha | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bobonaza | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento K10 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Copataza (Achuar) | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Fátima | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Intersección Cueva de los Tayos | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kawa | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Garza-1 | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo, 10 km N of | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Arajuno, headwaters of | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Curaray | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Huiyoyacu | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Talin | USMN 287933 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | MHNG 2309.097 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay In Situ | Bentley et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Casa de Eduardo Payaguaje | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE en Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Playas del Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | MHNG 2307.067 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Unspecified locality | UMMZ 84107 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Proyecto Minero Mirador | Photo by Raquel Betancourt |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tundayme, 10 km SE of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tundayme, 5 km E of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Unspecified locality | UMMZ 82891 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Valle del Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aguaruna Village | MVZ 163428 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Caterpiza | USNM 566611 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Kayamas | MVZ 163314 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Shaim | USNM 316642 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Upper Río Nieva | Wilson & Mena 1980 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Zona Reservada Santiago-Comaina | Jowers et al. 2020 |

| Perú | Loreto | Nauta | Jowers et al. 2020 |

| Perú | Loreto | Sargento Lores | Jowers et al. 2020 |