Published September 15, 2021. Updated February 19, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Sleepy Ground Snake (Atractus dunni)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Atractus dunni

English common names: Sleepy Ground Snake, Dunn’s Ground Snake.

Spanish common names: Tierrera dormilona, culebra tierrera de Dunn, culebra minadora de Dunn.

Recognition: ♂♂ 35.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=29.7 cm. ♀♀ 42.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=37.7 cm..1 Atractus dunni differs from other snakes in its area of distribution by having a round head similar in width to the neck, small eyes, dorsal scales arranged in 17 rows at mid-body, no preocular scale, and a dorsal pattern consisting of irregular 1-scale-wide dark spots with creamy borders disposed linearly on a brown ground color (Fig. 1).2,3 The belly is pale yellowish with various degrees of dark pigment.3 Atractus dunni is extremely similar to A. microrhynchus, A. iridescens, and A. esepe, but it has not been found living alongside any of these species, as it generally occurs at higher elevations.4 Atractus dunni differs from A. microrhynchus by lacking longitudinal lines on the dorsum, either complete or broken.4,5 Males of the Sleepy Ground Snake differ from females by having less ventral scales (125–139 vs 137–153), more subcaudal scales (28–43 vs 14–27), and a proportionally longer tail.1 Juveniles have a light yellow nape band.3

Figure 1: Adult male of Atractus dunni from Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve, Pichincha province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Atractus dunni is a locally frequent semi-fossorial snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed cloud forests, crops, pastures, and rural gardens near the forest border.2,6 This species is distributed in cold (mean annual temperature=11.88–18.67°C) areas of the Pacific slopes of the Andes where the annual precipitation ranges between 1000 and 2561 mm.1 Sleepy Ground Snakes are usually seen moving on the forest floor or crossing dirt roads and trails during warm and cloudy nights2,6 or rarely during the daytime.7 When not active, individuals are usually found hidden under logs, rocks, or in leaf-litter.3,6 The diet of A. dunni includes insect larvae and earthworms.2 These snakes rely mostly on their cryptic coloration as a primary line of defense. If handled, individuals usually just try to flee, but they can also use their sharp tail-tip for poking as well as flatten their body dorsoventrally to appear larger.6 Females of A. dunni lay clutches of 2–4 eggs under soft soil.2,6

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..8 Atractus dunni is listed in this category because it has been recorded in more than 10 localities (=27; see Appendix 1), occurs in more than 10 protected areas, and is distributed over an area that retains most (~72%) of its forest cover.9 Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.8 However, some populations are likely to be declining due to deforestation by logging and large-scale mining, especially in the provinces of Imbabura and Carchi.8,10

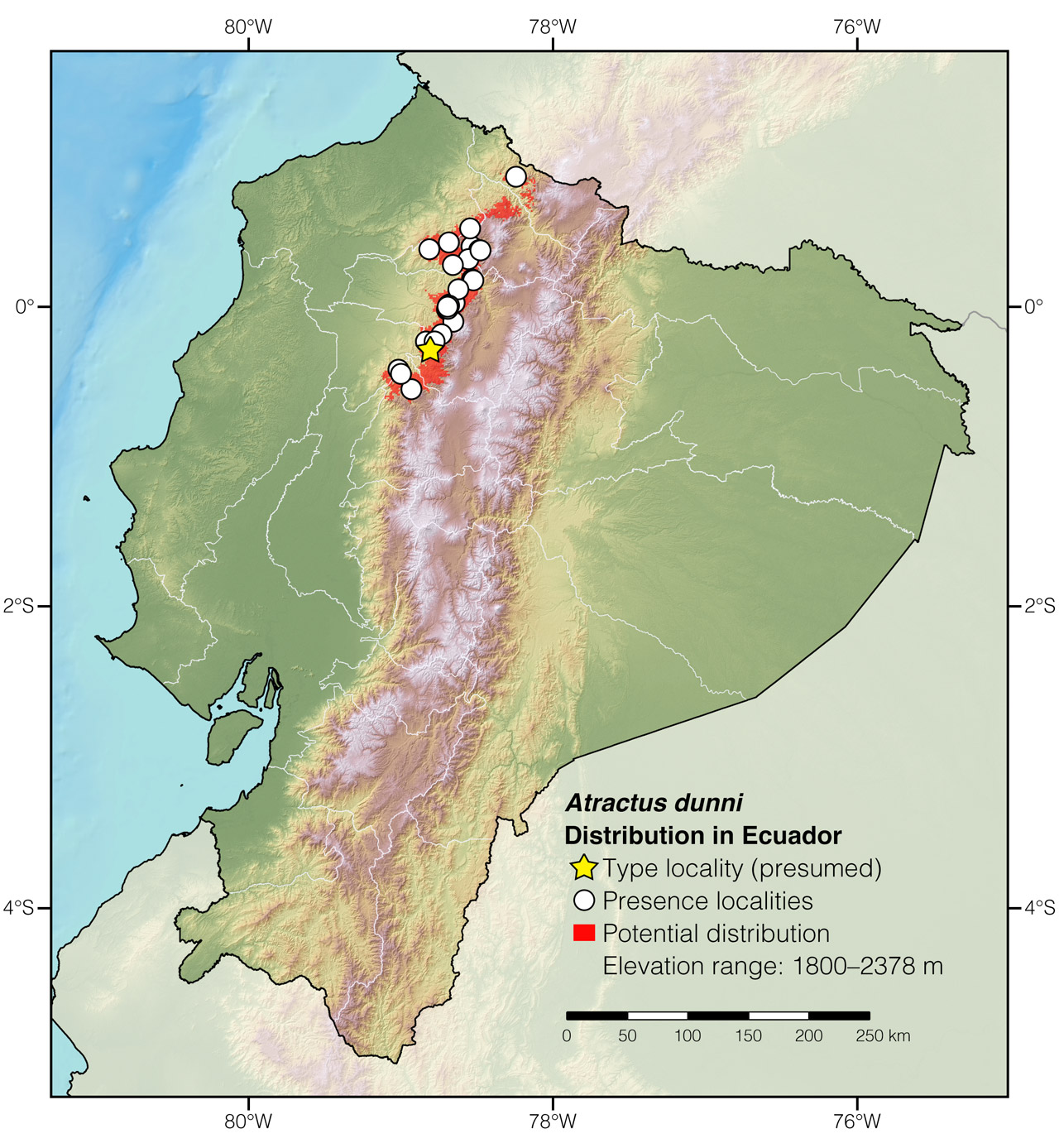

Distribution: Atractus dunni is endemic to an area of approximately 3,741 km2 along the Pacific slopes of the Andes of northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Atractus dunni in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Chiriboga, Pichincha province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Atractus, which is a latinization of the Greek word άτρακτος (=spindle),11–13 probably refers to the fact that snakes of this genus have a uniform width throughout the body and a narrow tail, resembling an antique spindle used to spin fibers. The specific epithet dunni honors American herpetologist Emmett Reid Dunn (1894–1956), of Harvard College, whose suggestion ultimately led Jay Savage to describe this snake species as new to science.5

See it in the wild: Dunn’s Ground Snakes can be seen at a rate of about 1–2 individuals per week in forested areas throughout their area of distribution. It is easier to find individuals right after sunset during a warm night, especially Río Guajalito, Otonga, Santa Lucía, and Bellavista reserves. The snakes may be located by scanning the forest floor and leaf-litter along trails at night or by looking under rocks and logs in pastures near forest borders.

Acknowledgments: This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Sleepy Ground Snake (Atractus dunni). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZNVA6317

Literature cited:

- Mejía Guerrero MA (2018) Revisión taxonómica de las serpientes tierreras Atractus del grupo iridescens Arteaga et al. 2017. BSc thesis, Quito, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 67 pp.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Cisneros-Heredia D (2005) Rediscovery of the Ecuadorian snake Atractus dunni Savage, 1955 (Serpentes: Colubridae). Journal by the National Museum, Natural History Series 174: 87–114.

- Arteaga A, Mebert K, Valencia JH, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Peñafiel N, Reyes-Puig C, Vieira-Fernandes JL, Guayasamin JM (2017) Molecular phylogeny of Atractus (Serpentes, Dipsadidae), with emphasis on Ecuadorian species and the description of three new taxa. ZooKeys 661: 91–123. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.661.11224

- Savage JM (1955) Descriptions of new colubrid snakes, genus Atractus, from Ecuador. Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington 68: 11–20.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photo by Nelson Apolo.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF (2017) Atractus dunni. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T50951065A50951074.en

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, Kohn S, Gavilanes G, Lynch RL, Hamilton PS, Maynard RJ (2019) A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Chocó-Andean Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ 7: e6400. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6400

- Woodward SP, Tate R (1830) A manual of the Mollusca: being a treatise on recent and fossil shells. C. Lockwood and Company, London, 750 pp.

- Beekes R (2010) Etymological dictionary of Greek. Brill, Boston, 1808 pp.

- Duponchel P, Chevrolat L (1849) Atractus. In: d’Orbigny CD (Ed) Dictionnaire universel d’histoire naturelle. MM. Renard, Martinet et Cie., Paris, 312.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Atractus dunni in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Gualpi | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Integral Otonga | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Cutzualo | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | 6 de Julio de Cuellaje | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | El Portal de Intag | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | El Refugio de Intag | Photo by Peter Joost |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Hacienda La Florida | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Intag | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Junín | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Santa Rosa de Intag | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Toisán | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bellavista Lodge | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Cambugán | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Verdecocha | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Chiriboga* | Savage 1955 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | La Unión–Río Cinto | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Llambo | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pacha Quindi Nature Refuge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pahuma Reserve | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Río Cambugán | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tambo Quinde | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandayapa Lodge | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandayapa, 1 km N of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Bosque Protector Río Guajalito | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Estación Experimental La Favorita | Arteaga et al. 2017 |