Published July 8, 2020. Updated November 19, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Ocellated Andean-Lizard (Andinosaura oculata)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Andinosaura oculata

English common names: Ocellated Andean-Lizard, Tropical Lightbulb Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija andina ocelada.

Recognition: ♂♂ 23.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.8 cm. ♀♀ 23.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.4 cm..1 The Ocellated Andean-Lizard (Andinosaura oculata) differs from most other lizards in its area of distribution by lacking prefrontal scales and having extremities long enough that the front and hind limbs overlap when pressed against its body.1 Adult males can be recognized by being more robust and by having reddish flanks with ocelli consisting of a black circle with a white spot in the middle. Adult females are brownish overall and lack ocelli (Fig. 1). Similar co-occurring lizards are A. hyposticta, which has black ventral surfaces densely stippled with yellow pigment,2 and R. yumborum, which has front and hind limbs that cannot reach each other.3

Figure 1: Individuals of Andinosaura oculata from Pichincha province, Ecuador: Séptimo Paraíso Lodge (); Santa Lucía Ecological Reserve (); Cascadas de Mindo (). sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Andinosaura oculata is a rarely seen cryptozoic (preferring moist, shaded microhabitats such as streams with abundant leaf-litter)1 lizard that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen montane forests, cloud forests, sugarcane plantations, and pastures with scattered trees.1,4 Ocellated Andean-Lizards are often seen at ground level during the daytime (mostly under leaf-litter or on soil, moss, and grass), but they can also use their prehensile4 tail to ascend to buttress roots and tree trunks up to 15 m above the ground.1 When not active, they hide under leaf-litter, logs, and rocks.1 Individuals have also been seen active at night.5,6 Adult males are territorial, fighting aggressively against each other by biting and pushing the opponent.6 Females lay up to three eggs in holes in the forest floor.1 When threatened, these shy reptiles flee into leaf-litter. If captured, they may bite or readily shed the tail.6 There are records of snakes (Erythrolamprus vitti, Mastigodryas pulchriceps, and Tantilla fraseri) preying upon the adults and eggs of A. oculata.1,7,8 Predation by owls has also been recorded.9

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Andinosaura oculata is proposed to be assigned in this category, instead of Endangered,10 following IUCN criteria11 because the species has now been recorded at 27 localities (including 15 protected areas) and is distributed over an area that retains most (~73.3%) of its original forest cover. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. However, some populations of A. oculata are likely to be declining due to deforestation by logging12 and large-scale mining, especially in the provinces Carchi and Imbabura,13 where only four populations are known.

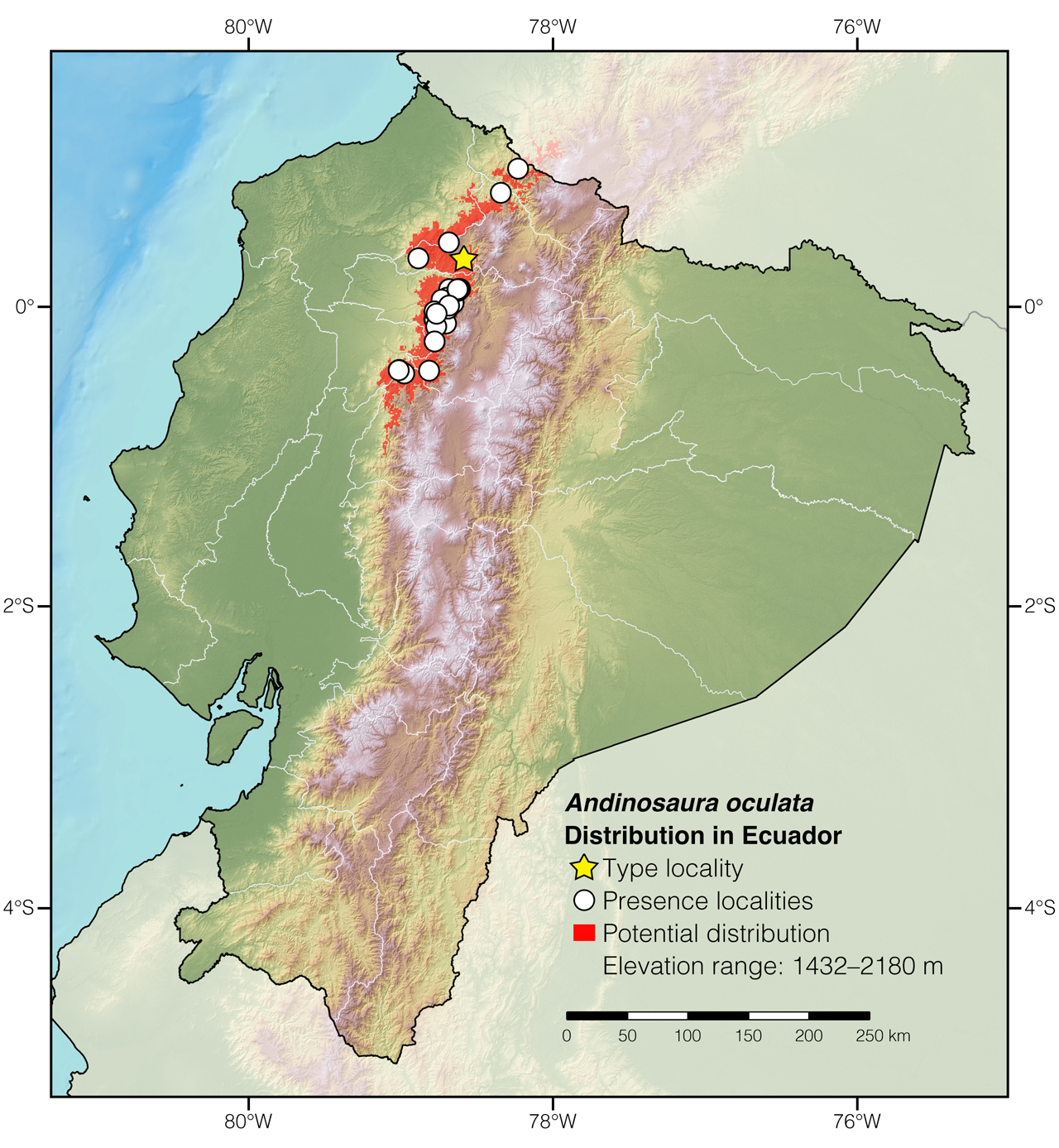

Distribution: Andinosaura oculata is endemic to an area of approximately 5,463 km2 in the Pacific slopes of the Andes in northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Andinosaura oculata in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Intag, Imbabura province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Andinosaura, which comes from the Spanish word andino (from the Andes) and the Latin sauria (=lizard), refers to the distribution of this group of lizards.14 The specific epithet oculata comes from the Latin oculus (=eye) and the suffix -atus (=provided with), and refers to the lateral ocelli.1

See it in the wild: Ocellated Andean-Lizards are recorded rarely, no more than once every few months, probably due to their secretive and presumed arboreal habits. At Santa Lucía Ecological Reserve, however, lizards of this species may be recorded weekly during leaf-litter surveys.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Connor Sullivan and Tony Nunnery for providing locality data and information about the natural history of Andinosaura oculata. This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Simon MaddockbAffiliation: Faculty of Science and Engineering, University of Wolverhampton, Wolverhampton, United Kingdom.

Photographers: Jose VieiracAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2023) Ocellated Andean-Lizard (Andinosaura oculata). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/NDQZ5372

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Sánchez-Pacheco SJ, Kizirian DA, Sales-Nunes PM (2011) A new species of Riama from Ecuador previously referred to as Riama hyposticta (Boulenger, 1902) (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae). American Museum Novitates 3719: 1–15. DOI: 10.1206/3719.2

- Doan TM, Castoe TA (2005) Phylogenetic taxonomy of the Cercosaurini (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae), with new genera for species of Neusticurus and Proctoporus. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 143: 405–416. DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2005.00145.x

- Maddock ST, Smith EF, Peck MR, Morales JN (2011) Riama oculata: prehensile tail and new habitat type. Herpetological Review 42: 277–278.

- Reyes-Puig C, Meza-Ramos PA, Dueñas MR, Bejarano-Muñoz P, Ramírez-Jaramillo SM, Reyes-Puig JP, Yánez-Muñoz MH (2015) Guía de identificación de anfibios y reptiles comunes de la Estación Experimental La Favorita. Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad, Quito, 79 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Maigua-Salas S, Betancourt R, Yánez-Muñoz MH (2019) Erythrolamprus vitti. Diet and behavior. Herpetological Review 50: 156–157.

- Maddock ST, Smith EF, Peck MR, Morales JN (2011) Tantilla melanocephala (Black-headed Snake). Diet. Herpetological Review 42: 620.

- Dueñas MR, Valencia JH (2019) Andinosaura oculata (Tropical Lightbulb Lizard). Predation. Herpetological Review 50: 134.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Valencia J, Brito J, Almendáriz A, Munoz G (2017) Riama oculata. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T178672A54447131.en

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- Tolhurst BA, Aguirre Peñafiel V, Mafla-Endara P, Berg MJ, Peck MR, Maddock ST (2016) Lizard diversity in response to human-induced disturbance in Andean Ecuador. Herpetological Journal 26: 33–39.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, Kohn S, Gavilanes G, Lynch RL, Hamilton PS, Maynard RJ (2019) A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Chocó-Andean Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ 7: e6400. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6400

- Sánchez‐Pacheco SJ, Torres‐Carvajal O, Aguirre‐Peñafiel V, Sales-Nunes PM, Verrastro L, Rivas GA, Rodrigues MT, Grant T, Murphy RW (2017) Phylogeny of Riama (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae), impact of phenotypic evidence on molecular datasets, and the origin of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta endemic fauna. Cladistics 34: 260–291. DOI: 10.1111/cla.12203

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Andinosaura oculata in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Carchi | Dracula Reserve | Fundación EcoMinga’s blog |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Integral Otonga | David Salazar, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Damas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Intag | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Manduriacu Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Santa Cecilia | Maigua-Salas et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bellavista Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Mindo-Nambillo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cascadas de Mindo | Photo by Peter Muddle |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cascadas de Nambillo | Dueñas & Valencia 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cooperativa Primero de Mayo | Photo by Segundo Imba |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hacienda San Vicente | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Las Gralarias Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Las Tangaras Reserve | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Los Armadillos | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo-Nambillo Protected Forest | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegal, vicinity of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. (2012) |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegalito | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegalito, 3 km E of | Sánchez-Pacheco et al. (2012) |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pacha Quindi Nature Refuge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Intillacta | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Ecological Reserve, cascada 3 | Connor Sullivan, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Ecological Reserve, cerca de la piedra de lavar | Connor Sullivan, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Ecological Reserve, potrero | Connor Sullivan, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Saragoza–Río Cinto | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Séptimo Paraíso Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tamboquinde | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi | Kizirian 1996 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Estación Experimental La Favorita | Reyes-Puig et al. 2015 |