How do you create a book about all the reptiles of a mega-diverse country?

Reptiles of Ecuador | Story of the book

By Alejandro Arteaga. August 2023.

Everyone grasps the fundamental concept of a field guide: a book designed to aid in the identification of species in the wild while offering pertinent information about them. Unlike encyclopedias, field guides strive to provide information about EVERY species within a specific animal or plant group in a given geographical area. Field guides can be comprehensive when the number of species covered is limited. For instance, a field guide centered on the crocodiles of the Americas would include only ten species.

However, how do you create a comprehensive field guide about a species-rich animal group in a mega-diverse country?

To answer this question, I will tell you the story of the Reptiles of Ecuador book, a meticulously created field guide that has gained attention due to its expansive scope, novel photographic style, open-access nature, and funding strategy.

The idea for a Reptiles of Ecuador book emerged in 2010 from a casual conversation with a wildlife photographer friend. I posed a question:

Why are there field guides for birds and mammals of Ecuador, but none dedicated to reptiles?

His response was candid: “I’m not sure... you should consider writing one.”

Andrea Ferrari, editor in chief of Anima Mundi, enjoys reading the Amphibians and Reptiles of Mindo book. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

His suggestion caught me off guard. I had never contemplated writing a book and, even though I found the concept intriguing, at 18 years old and just commencing my studies in biology, I did not feel qualified for such a task.

Throughout my childhood, I had drawn inspiration from field guides spanning diverse animal groups, ranging from insects to birds, and more recently, amphibians and reptiles. Consequently, I had a general idea of how a field guide about herpetofauna should look like.

But I had no idea how write one.

How could I possibly compile a book encompassing ALL reptile species within a country as biodiverse as Ecuador? The nation boasts a staggering 500 reptile species!

There are 500 species of reptiles in Ecuador, including the Emerald Tree-Boa (Corallus batesii), a snake that lives in the canopy of the Amazon rainforest and is seen no more than once every few years. Photo by Jose Vieira.

Some reptiles in Ecuador, like the Northern Caiman-Lizard (Dracaena guianensis), are not necessarily rare, but extremely hard to catch. Photo by Jose Vieira.

The question brought to mind a timeless query often found in children’s books: how do you eat an elephant?

The answer, as it goes, is: one bite at a time.

This logic resonated with me.

Interestingly, during a similar period in my life, I encountered the concept of the “minimum viable product.” An entrepreneurial idea, it encourages startups to test the feasibility of their project by creating a prototype.

Embracing this concept, I reached out to my photographer friend Lucas Bustamante and my academic mentor Juan Guayasamin with an idea: to create a book about the herpetofauna of Mindo, a small valley in Ecuador known as a destination for birding and adventure sports. The fauna of Mindo is a much smaller subset (=101 species) of the country’s overall diversity, which allowed for much faster testing of our two hypotheses:

Firstly, does genuine interest exist for a publication focused on the herpetofauna of Ecuador? Secondly, do we have what it takes to complete the work and have it published?

In a meeting with Lucas and Juan, I articulated the plan: to photograph every single species of amphibian and reptile of Mindo in roughly the same position and on a white background. Accompanying these images would be comprehensive accounts, complete with detailed maps—ultimately shared online and accessible entirely free of charge.

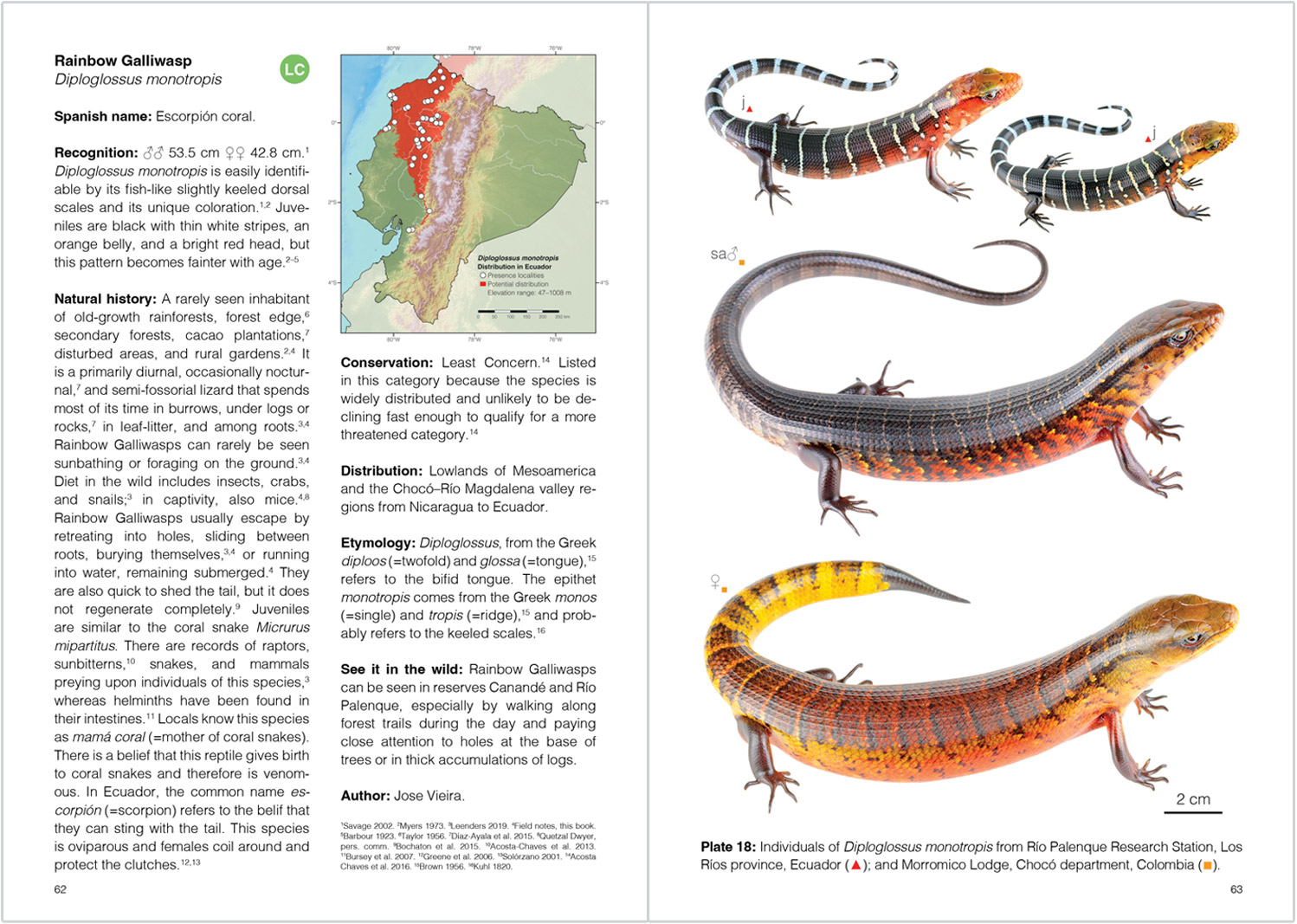

Sample pages of the upcoming Reptiles of Ecuador book.

You might be wondering about the rationale behind the standardized positioning and white background. After all, the majority of herpetofaunal field guides portray the animals on “natural” substrates and on varying poses. My usual explanation centers on the fact that the white background photos facilitate the creation of plates akin to those found in birding field guides. However, a more pivotal reason lies in the aesthetic appeal of neatly arranged images (I confess I may have an OCD).

Similarly, you might be wondering about the rationale behind providing information free of charge. Could this not potentially undermine future book sales?

Biologist Sebastián Di Doménico photographing a Chocoan Blunt-headed Tree-Snake (Imantodes chocoensis) at an improvised field lab during an expedition to the Chocó rainforest in northwestern Ecuador. Photo by Jorge Castillo.

A white background image of an Eyelash Palm-Pitviper (Bothriechis schlegelii). Photographs like these were the goal of each expedition. Photo by Jorge Castillo.

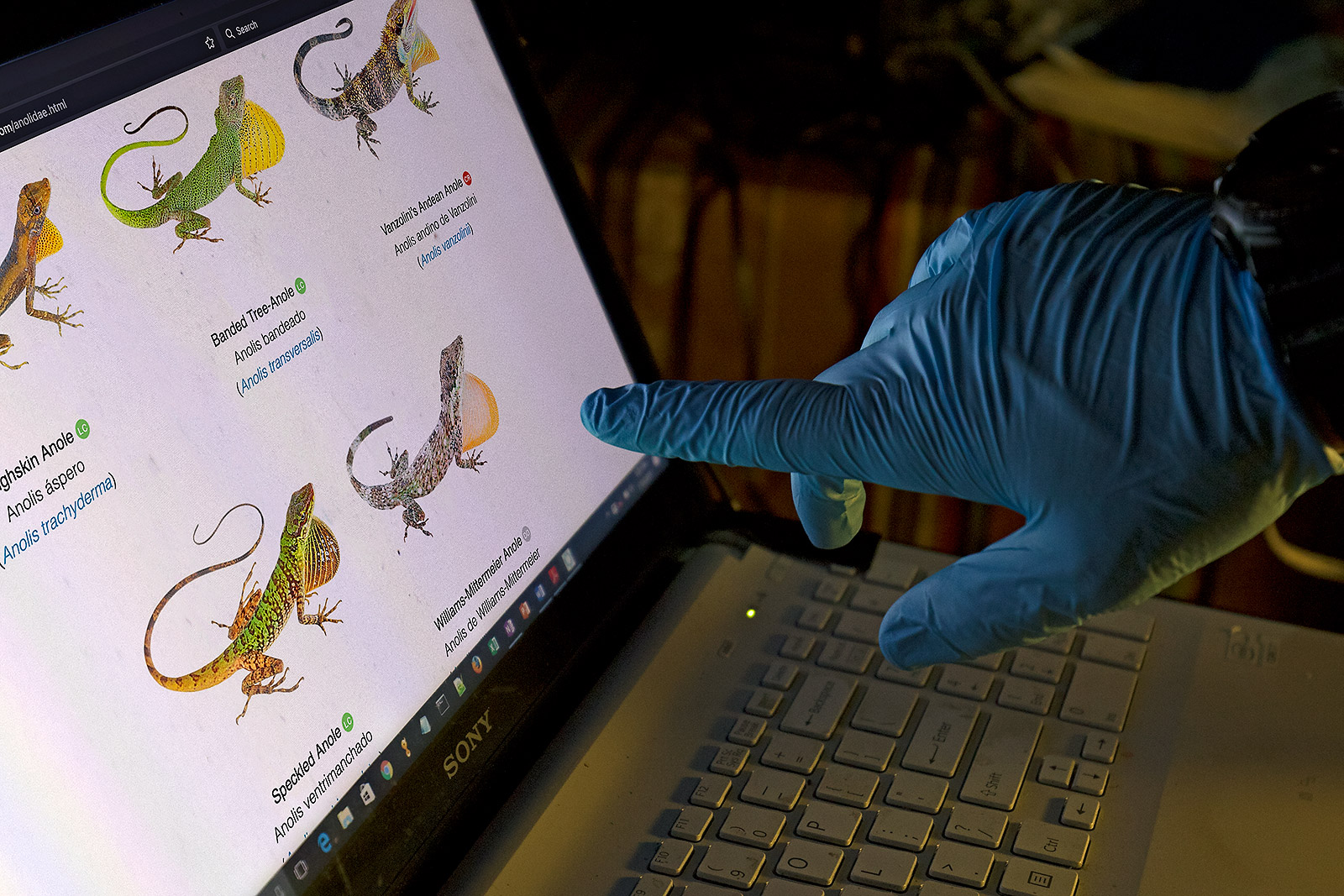

We decided to make the contents of the Reptiles of Ecuador book available for free online in the form of a dynamic catalogue. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

As it turns out, offering the information online for free served as a litmus test to determine whether any demand existed for a complete book about this topic. Astonishingly, demand did manifest! Each day, several dozen people frequented our online book platform.

This inspired us to go out into the field and find all the species.

Before long, we found ourselves grappling with the realization that locating the target reptiles within the cloud forest presented not only an immense challenge but also demanded a significant investment of time and money.

Biologist Alejandro Arteaga explores the equatorial rainforest during an expedition for the Reptiles of Ecuador book. Photo by David Jácome.

Researcher Alejandro Arteaga examines a Short-nosed Ground Snake (Atractus microrhynchus) during a night excursion in Mindo. Photo by Karine Aigner.

Field team congregated around the fireplace during an expedition to the cloud forest. Photo by Frank Pichardo.

An Orcés’ Blue Whiptail held besides the logo of Tropical Herping. Photo by Jose Vieira.

Also, it soon became apparent that both publishers and our own university were uninterested in financially supporting the book.

In response, one of my co-authors and I devised a strategy: to establish an eco-tourism company to fund the essential fieldwork as well as to take visitors precisely to the forest localities where the target species could be found.

We named this initiative Tropical Herping.

To our knowledge, we were pioneers in offering eco-tours focused on finding and photographing wild amphibians and reptiles, at least in Ecuador. Initially, it seemed like there wasn’t a market for such an undertaking. However, after a few months, our tours gradually began attracting attention, ultimately securing our first clients, Italian photographers Andrea and Antonella Ferrari, no less. They provided much needed advice on how to improve our then nascent operation and inspired us to delve into the world of photographic tourism.

Remarkably, our strategy worked! Through these initial excursions and the proceeds generated from eco-tourism, we succeeded in photographing the majority of amphibians and reptiles inhabiting the Mindo region.

Over the next couple of years, we replicated this successful approach, progressively capturing images of nearly all 101 species. This even extended to species once deemed impossible to locate, such as the Pinocchio Anole (Anolis proboscis)—an elusive lizard believed to be extinct for nearly 50 years!

The finding of the Pinocchio Anole (Anolis proboscis), a species not seen since 1953, was the major highlight of the Amphibians and Reptiles of Mindo book. Photo by Frank Pichardo.

Field biologist Jose Vieira ascends to the cloud forest canopy to search arboreal lizards. Photo by Frank Pichardo.

Suddenly, I no longer felt unqualified for the mission. Furthermore, I was having the time of my life: exploring the cloud forests alongside friends while photographing my favorite group of animals. It was akin to living out a real-world Pokémon.

Then came the museum part. This stage entailed visiting zoological museum collections to examine alcohol-preserved specimens. The purpose was to extract measurements and other pertinent data. Curiously, much of this work took place in museum collections outside Ecuador, such as in the United States and Europe, where obtaining access to voucher specimens was more straightforward than within Ecuador.

Biologist Alejandro Arteaga examines alcohol-preserved specimens at a herpetologial museum collection in Quito. Photo by David Jácome.

Biologist Alejandro Arteaga examines alcohol-preserved specimens at the American Museum of Natural History, New York. Photo by Jorge Castillo.

Much of the preparation of the book’s written content took place during expeditions. At that point, we were spending about 50–60% of the time in the field, so any place with a roof and some electricity became our “office.”

Yet, the writing process for the book posed the most formidable challenge. It consisted of prolonged days and nights spent either ensconced within the library or seated before a computer screen.

The work included compiling information from scientific papers, books, or from online databases. It also necessitated telephone conversations with people who had seen the various species. I discovered that putting together a comprehensive species account would take anywhere from a day to one week of dedication.

“This is going to take forever,” I thought. Moreover, the information still needed to be edited by experts on each species group, a process known in academic circles as peer-review.

After a span of four years, we arrived at the publication phase.

Despite our initial success, we never obtained the financial support of a publisher. Consequently, we opted for self-publication. Our funding strategy consisted on offering sponsorships (essentially logo in book) to various institutions. To our surprise, 10 institutions (from hundreds approached) said yes. While not all provided monetary support for the publication, some extended in-kind assistance, including lodging/food during expeditions or a venue for the book’s premiere.

Dr. Juan Guayasamin reading the Amphibians and Reptiles of Mindo book. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

Self publishing this first book was the best decision we made (or, to put it more accurately, were forced to make). In the absence of a publisher, we had no option but to sell the books ourselves. Would anyone buy them?

To our amazement, the first day saw hundreds of copies sold. Over the ensuing year and a half, 3,000 copies were sold. The minimum viable product worked!

Three good things arose from controlling the sales of the book.

- Buyers provided direct feedback to improve future versions of the book.

- We established long-term relationships with users of the book.

- Funds that would otherwise got to the publisher were allocated towards the next book.

Having completed this mission, we set our sight on the reptiles of the Galápagos. Although a comparatively low number of species (58) inhabit the enchanted islands, photographing them proved to be the most formidable challenge we had encountered.

The Galápagos Islands is home to 58 species of reptiles, including the iconic Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

Persuading the Galápagos National Park Directorate to even consider our proposal to photograph the reptiles of the islands took an entire year.

To our profound dismay, the response was PROJECT DENIED without explanation. Our pleas for clarification went unanswered for weeks. Finally, a national park officer told us: “You could be The Pope, but we will never allow you to lay a hand on a Galápagos Iguana, much less use a pair of flashes to photograph them.”

This verdict was calamitous! There was no way the Reptiles of Ecuador book could be published without images of the Galápagos species.

Surely, we had to do something.

The mention of The Pope gave us an idea. What if we go directly to the President of Ecuador? Surely, he can endorse our project.

Although we had no way of reaching the head of state directly, we found a way to finagle a meeting with its Ministro de Ambiente (=Minister of Environment), also known to be the President’s “right hand.”

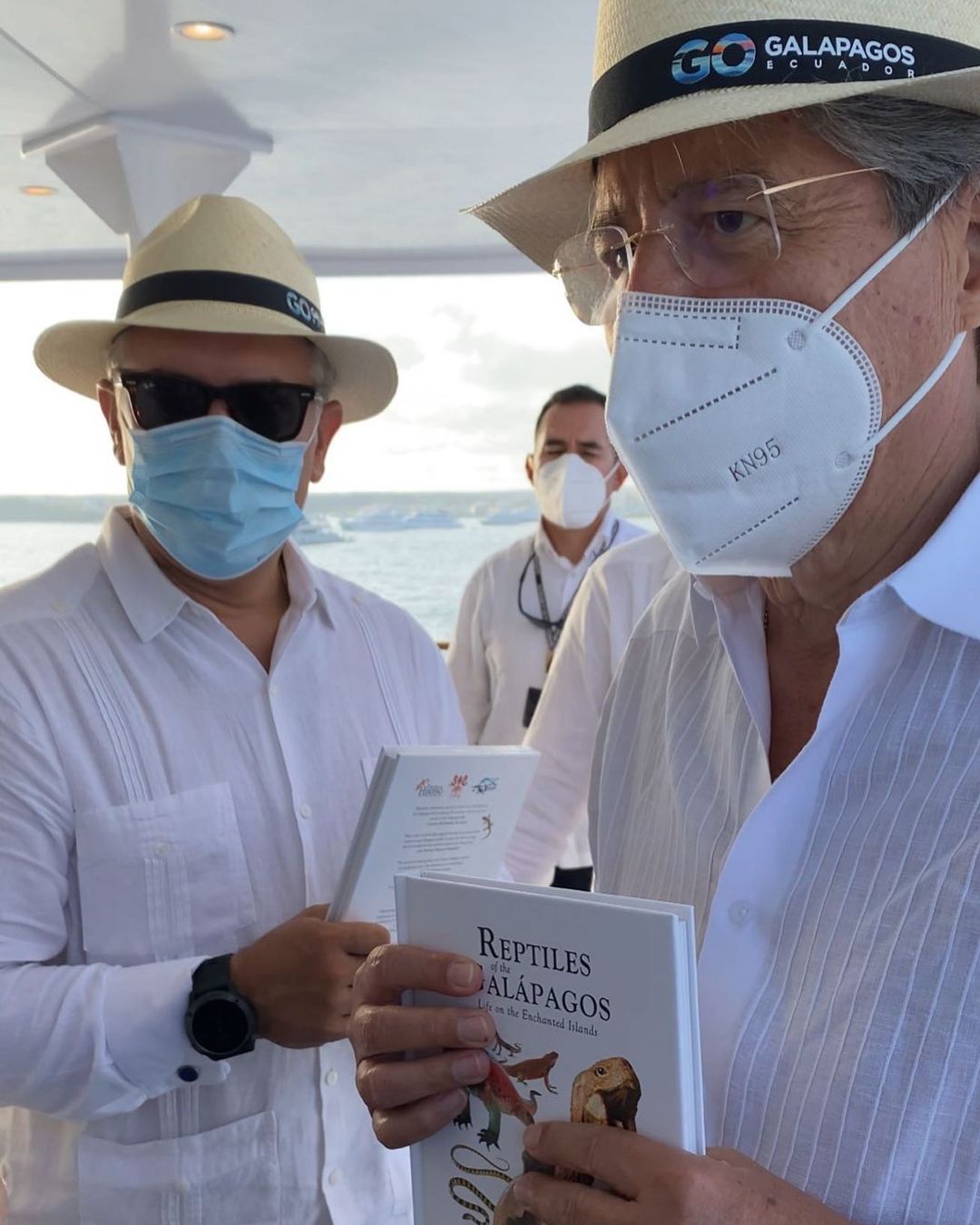

The heads of state of both Ecuador and Colombia holding the book Reptiles of the Galápagos. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

The Ministro became enamored with the Mindo book and the idea of a broader Reptiles of Ecuador monograph.

He affirmed he would endorse our proposal contingent upon our commitment to also publish a book exclusively about the reptiles of the Galápagos.

We gladly accepted.

Having secured permits for both research and photography in the Enchanted Islands, a new challenging reality confronted us: a single Galápagos expedition to photograph 1–4 species costed between $5,000 and $10,000.

How on Earth were we going to procure the funds necessary to photograph all 58 species?

Though we submitted applications to more than a dozen research grants, none was approved.

Then, an idea took shape: crowdfunding.

At this point, we had become used to sharing our book campaign's progress on social media. We routinely posted photos and videos of each and every Pokémon found as a way to show their beauty. Several thousand people were following our work daily and many chose to contribute towards reaching our crowdfunding goal.

Sponsorships and institutional affiliations also helped.

Finally, Tropical Herping had evolved into an established tourism agency, offering monthly tours and thereby able to contribute to funding a portion of the fieldwork.

We approached tour agencies, NGOs, Zoos, and universities and offered sponsorships that included a number of books to help offset the costs of their financial support.

It worked!

Biologist Jose Vieira dives inside the burrow of a Pink Iguana at the rim of Wolf Volcano, Isabela Island, Galápagos. Photo by Lucas Bustamante.

The search for the Pink Land-Iguana (Conolophus marthae) was the most iconic expedition of the Galápagos chapter. Photo by Jose Vieira.

After three years intensively exploring the Islands, we successfully captured images of 55 species of Galápagos reptiles, including the recently deceased Lonesome George, the enigmatic Wolf Leaf-toed Gecko, and the iconic Pink Land-Iguana. By this time, field biologist Jose Vieira had joined the team full-time and did most of the heavy lifting in the field.

Somehow, we even convinced the GIGANTIC Galápagos tortoises onto the white background for a snapshot or two.

Biologist Jose Vieira photographs a Wolf Volcano Giant-Tortoise (Chelonoidis becki) at the rim of Wolf Volcano, Isabela Island. Photo by Jorge Castillo.

The three-year Galápagos chapter costed over $200,000 and nearly claimed our lives, more than once. At one point, our team was left stranded on an Island. On another, two of us narrowly avoided drowning while attempting to capture a sea turtle. Finally, on Santa Fe Island, I accidentally stepped on a sea-lion at night (my headlamp was broken) and plummeted off a cliff when the enormous male pinniped bellowed and scared the living hell out of me.

But it was all worth it. In 2019, our efforts culminated in the publication of Reptiles of the Galápagos, a book that set the stage for the subsequent four-year endeavor to complete the comprehensive Reptiles of Ecuador book.

Authors of the Reptiles of the Galápagos at the book’s premiere in Puerto Ayora in November 2019. Photo by Milton Bustamante.

Gabriela Morales and Nathaly Padilla supported us during the entire book creation campaign as well as at the premiere in Puerto Ayora in November 2019. Photo by Milton Bustamante.

Much like the Mindo book, the Reptiles of the Galápagos was self-published, and the entire print run sold out within a mere few months. This allowed us to fuel part of the next stage of the broader Ecuador book, though not entirely.

Photographing the remaining nearly 400 species (out of 500 in total) demanded an additional three years and necessitated a wholly innovative crowdfunding approach. The reason? Some mainland Ecuador reptiles are so rare that numerous expeditions to the same site are needed to find even one individual.

For instance, two species of presumed extinct lizards were rediscovered as part of this book’s project. Prior to this effort, neither had been photographed alive (read press release here).

Finding the Orcés’ Blue Whiptail required interviews with local people, setting up pitfall traps with drift fences, and securing individuals for a conservation program. Photos by Jose Vieira.

First ever image of an adult male Orcés’ Blue-Whiptail (Holcosus orcesi), considered by the IUCN to be the lizard species closest to extinction in Ecuador. Ten field trips to the type locality were needed to photograph a single individual. The first nine expeditions yielded only rumors and a flash sighting. Photo by Jose Vieira.

Put together, these recurrent expeditions would prove more costly than those in the Galápagos.

To address this challenge, alongside our established fundraising methods (sponsorships and social media crowdfunding), we launched the “Adopt a Reptile” campaign. Through this initiative, supporters of the book could symbolically adopt their favorite Ecuadorian reptile. Though unconventional, this idea achieved tremendous success and facilitated funding for numerous expeditions.

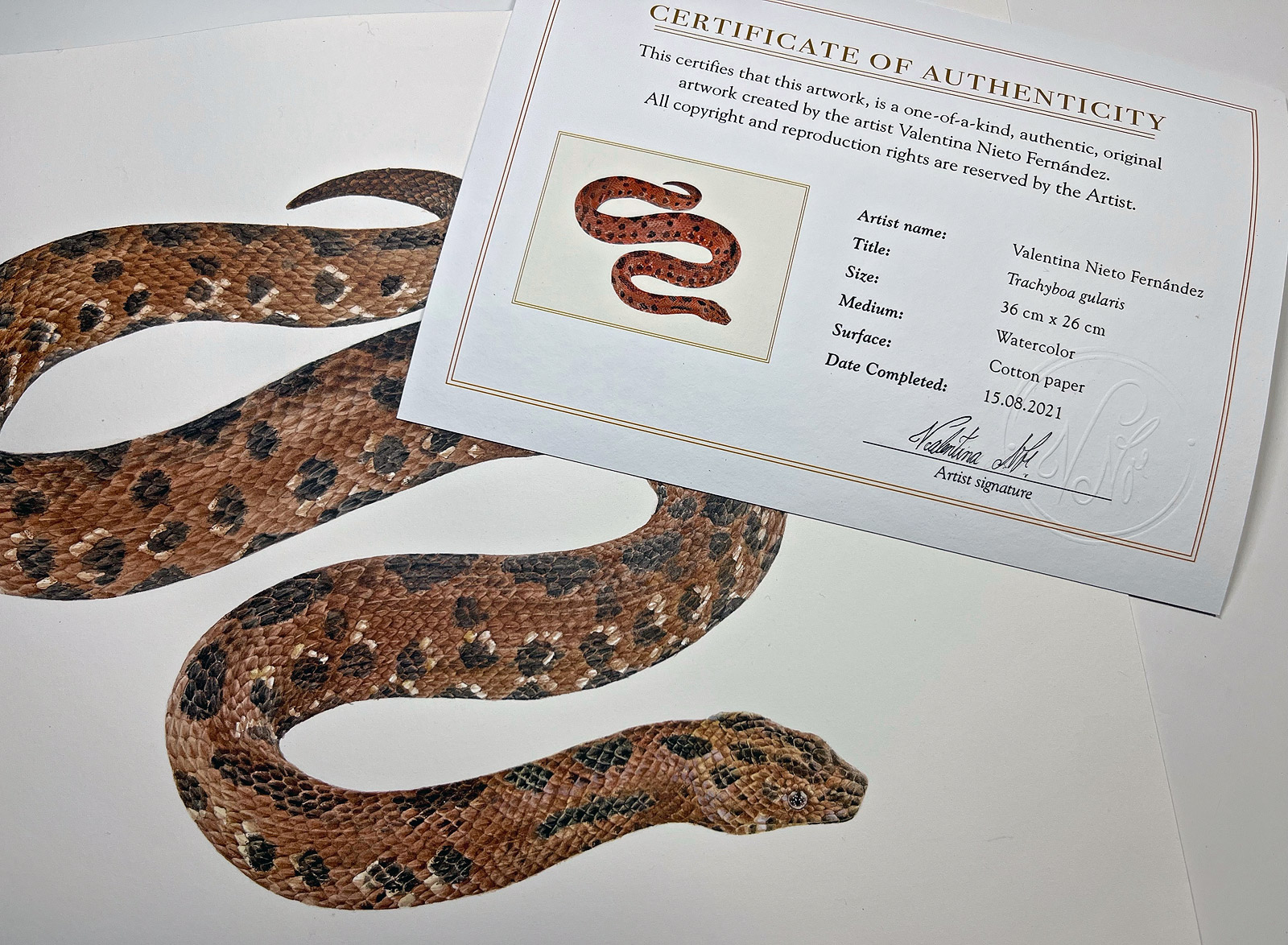

Remarkably, after 13 years of exploring Ecuador, certain species continue to elude our cameras. A notable example is the Southern Eyelash-Boa (Trachyboa gularis), which has remained unseen for three decades. Our seven expeditions to search for this boa failed.

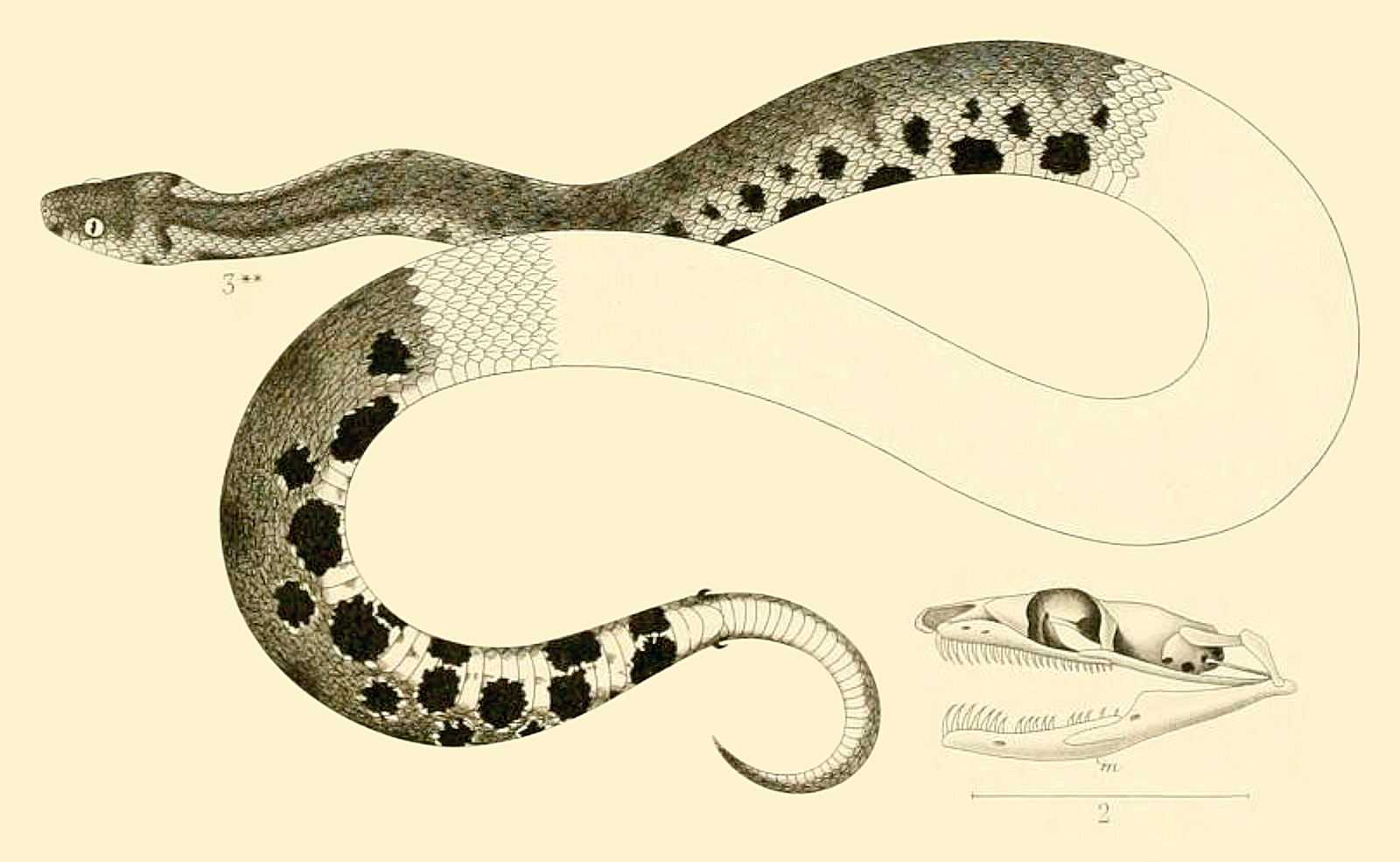

Illustration of a Southern Eyelash-Boa (Trachyboa gularis) created in 1861. This species was last seen alive 30 years ago by a farmer nearby the town Vinces, Los Ríos Province, Ecuador.

Herpetologists Amanda Quezada, Jose Vieira, and Eric Osterman sample a swamp where individuals of the Southern Eyelash-Boa had been collected in the past. Photo by Frank Pichardo.

Lucas Bustamante and Jose Vieira carrying a Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus). The adult of this species was photographed during later stages of the book due to the logistics of placing such a gigantic snake on a white background. Photo by John Martin.

Consider the following: some reptile species in Ecuador, such as fossorial snakes, are so rare that they have NEVER been photographed alive. Just a few weeks ago, we photographed one such species, which had been cataloged as “lost” for decades. The picture of this mythical snake will be revealed for the first time ever in the Reptiles of Ecuador book.

Thankfully, the book’s team has expanded beyond the original three authors, amplifying the prospects of encountering rare species. Field biologists such as Frank Pichardo, Amanda Quezada, and Eric Osterman have successfully located many elusive species. Also, each expedition is usually assisted by volunteers, park rangers, members of indigenous communities, and even children.

We have also established a network of “friends of the Reptiles of Ecuador book,” through which partners residing in remote areas notify us whenever a “legendary Pokémon” makes an appearance. Among this group of allies, three individuals, Diego Piñán, Regdy Vera, and Eduardo Zavala, stand out for having found some species of snakes that were deemed impossible to find.

Despite these efforts, white background photographs of approximately 35 exceedingly rare species will probably not be featured in the first edition of the book.

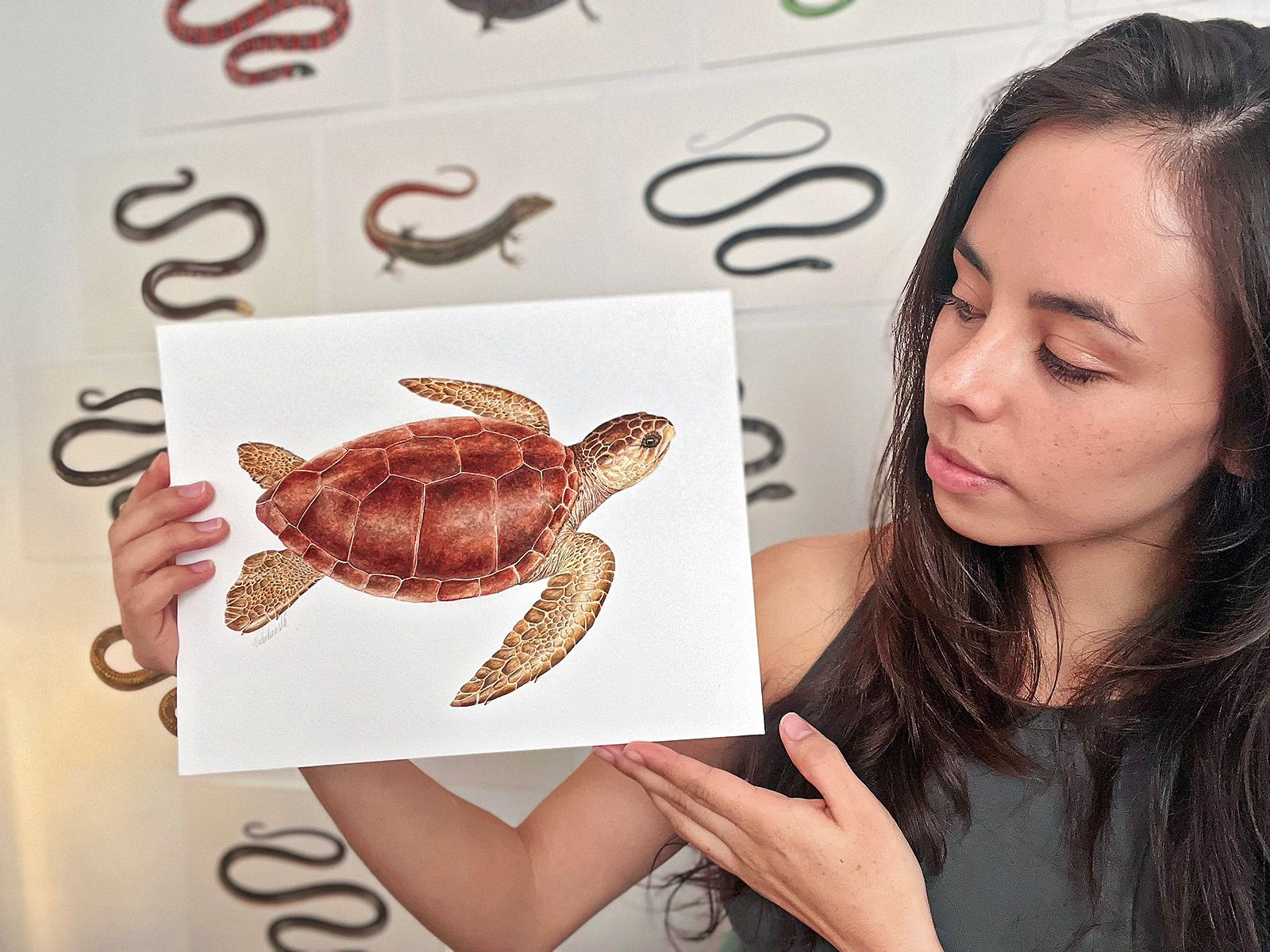

As an alternative strategy, artist Valentina Nieto is reviving these lost species through scientific illustration, and the outcomes are remarkable.

While we have now photographed or illustrated Ecuador’s entire herpetofauna, the project remains unfinished. Roughly 30% of the species accounts are yet to be written. This is the most arduous drawn-out phase of the book creation and requires thousands of hours of literature research, museum work, editing, and peer-review.

Artist Valentina Nieto illustrated the Loggerhead (Caretta caretta), a sea turtle that has only been spotted four times in Ecuadorian waters.

Illustrations created by artist Valentina Nieto for the Reptiles of Ecuador book.

Artist Valentina Nieto created stunningly detailed illustrations depicting the 35 Ecuadorian reptile species we could not photograph. As a way to help the book’s fundraiser, supporters of the book can claim one of the remaining illustrations signed by the author with the certificate of authenticity.

Curating the content, coding the accompanying website of the book, and publishing the material online accounts for 50% of our time and cost expenditures during this later stage of the project.

However, acquiring funding for literature review and coding doesn’t possess the allure of selling the concept of an expedition to photograph the Pink Iguana.

Nevertheless, we found a solution.

Throughout this story, I have indicated that there are 500 species of reptiles in Ecuador, but this is not entirely accurate.

The reason is the following.

In the process of exploring Ecuador’s herpetofauna for the past 13 years, our team has unveiled the existence of about 10 new reptile species.

These reptiles are not only entirely new species; some are absolutely stunning, so stunning that it is remarkable they remained undiscovered until now.

The Marley’s Snail-eating Snake (Sibon marleyae), named after conservationist Brian Sheth’s daughter, was discovered as a result of the expeditions of Reptiles of Ecuador book project. Photo by Frank Pichardo.

This new species of miniaturized leaf-litter gecko (genus Lepidoblepharis) is one of the new species discovered during the expeditions for the Reptiles of Ecuador book project. It is still unnamed. Photo by Alejandro Arteaga.

The realization that Ecuador harbors charismatic yet unnamed reptiles sparked an idea: to offer philanthropists the opportunity to chose the name of these new reptile species in exchange for contributing to the book and the research necessary to formally describe these creatures.

This innovative funding approach has swiftly become our most popular strategy, propelling us towards the culmination of the final one-third of the book’s written content.

Ok, I know what you are thinking: when will the book be completed?

This is a question I receive daily and one to which I reply: “Rome was not built in one day.” We are making daily progress (updated daily here) towards completing the remaining 30% of species accounts and need your help raising the funds needed for such an activity.

How can you contribute?

…or even aid us in locating one of the missing legendary Pokémons. Find a Southern Eyelash-Boa and I will include your photo with a big THANK YOU somewhere in the book (and I assure you, I am entirely serious about this).