Published April 8, 2022. Updated February 14, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Boidae | Eunectes murinus

English common names: Green Anaconda, Common Anaconda.

Spanish common names: Anaconda verde, serpiente de agua, culebra de agua.

Recognition: ♂♂ 3.39 mMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=3.31 m. ♀♀ 6.6 mMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1,2 The Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus) is the World’s second longest snake, and is clearly the heaviest (up to 104.4 kg).3,4 Anacondas of 11.4 m in total length or weighing 227 kg have been reported,5,6 but not confirmed. The body of E. murinus is adapted for an aquatic lifestyle and includes eyes and nostrils on the top of the head and a color pattern that blends in with aquatic vegetation.2,4 The dorsal coloration consists of 36–45 dark brown or black blotches and a lateral row of light-centered ocelli on a deep olive background color.7 The top of the head is also olive and is accompanied by a broad reddish brown to orangish cream postocular stripe bordered above and below by thinner black stripes.4 The sheer body size of this snake, in combination with its unique coloration, is enough to separate it from all other Ecuadorian serpents. The species can be further differentiated from other Amazonian boas by having very narrow ventral scales.8 Anacondas are considered to be primitive (basal) among the boa family (Boidae).9 Evidence for this includes the presence of anal hooks or claws reminiscent of the thighbone.2,4 Males of E. murinus, though remarkably smaller than females, have absolute longer spurs (7.47 mm) than females (5.13 mm) regardless of the larger female size.2

Figure 1: Individuals of Eunectes murinus: Casanare department, Colombia (); Sani Lodge, Sucumbíos province, Ecuador (). j=juvenile.

“It is an undisputed fact that anacondas devour cattle and horses, and the general belief in the country is that they are sometimes from sixty to eighty feet long.”

Alfred Russell Wallace, British naturalist and explorer, 1853.10

Natural history: Eunectes murinus is a semi-aquatic boa that inhabits swamps, marshes, rivers, lagoons, flooded forests, and seasonally flooded savannas.4,11,12 The species occurs in higher densities (up to 0.36 individuals/ha) in savannas than in rainforests.2 Green Anacondas are bulky and heavy reptiles that move slowly on land and are thus seldom found outside of the water.2 They spend the majority (~86%) of their time in the water or at the water’s edge (14%)2 and they seem to prefer shallow (less than 50 cm deep) water.2 During sunny days, individuals (specially breeding females)13 emerge to bask on large rocks, termite mounds, on the river bank,4,11,14 or on bushes or branches of trees overhanging the water up to 10 m above the surface.4,15,16 When not active, they hide in crevices, caves, among the roots of aquatic plants, or deep under mud.2,17 Even though Green Anacondas are good swimmers and occasionally pass streams of moving water, they seem to avoid currents and prefer areas of slow-moving water bodies with medium to dense aquatic vegetation.2 Occasionally, these boas (specially males during the breeding season) are seen crawling on dry land or crossing roads.2,14

Green Anacondas appear to be active throughout the day and night, but avoid being out during the hottest hours of the day.2,11,13 The home range size of non-breeding females and males of Eunectes murinus has been estimated to be 0.091–37.4 hectares (about the size of 0.1–52 soccer fields), with the former figure being in the dry season in a rainforest locality and the latter figure being during the rainy season in the savanna ecosystem.2,18 Green Anacondas routinely perform migratory movements averaging 1.3 km between the areas they use during the dry and rainy seasons.2 Throughout pregnancy, breeding females have much smaller home range sizes (about 0.01 ha) and bask regularly.2 Non-breeding animals are seldom seen basking.2 During the dry season in the Llanos region in Venezuela, when ponds and lagoons dry up, large numbers of anacondas (up to 34 in a 10x20 meters area) may be found congregated around the few remaining mud holes.2

Green Anacondas are ambush opportunistic predators that will take any prey they can kill and swallow.2,19 They wait submerged with only the eyes and nostrils above the water surface and prey primarily on animals that come down to drink at the water’s edge.4 The prey is killed by constriction.7 Smaller anacondas eat mostly birds17 while larger animals switch to mammals and reptiles as they grow.2,19 Prey items include mammals (capybaras,2,13 agoutis,14 small rodents,19 deer,1,4,13 tapirs,14,19 cattle,19 water buffalo,19 wild boar,19 opossums,19 anteaters,4 porcupines,20 armadillos,21 otters,19 monkeys,14 foxes,19 dogs,4 cats,19 and sheep4), birds (more than 20 species have been identified, mostly water birds such as jacanas, ducks, and herons)2,4,19 crocodilians (Caiman crocodilus2,4 C. latirostris,19 C. yacare,19 Melanosuchus niger, and Paleosuchus trigonatus11), turtles (Kinosternon scorpioides,19 Mesoclemmys gibba,19 Podocnemis expansa,2 and P. vogli2), snakes (Boa constrictor19 and Helicops angulatus22), lizards (Iguana iguana,2 Tupinambis cryptus2 and species in the genus Kentropyx14), frogs,8 and fish (including sharp-skinned catfish2,15 and armored catfish15,19). After a meal, these boas can go for several weeks without eating or moving at all.

Though primarily shy and secretive, Green Anacondas are quite fierce and wonderfully strong. When disturbed, they can strike repeatedly or bite-and-hold while throwing body coils around their attacker.4 Smaller anacondas are much more aggressive and disposed to bite than larger ones.2 When restrained, individuals of all sizes will release a foul anal musk and may produce long, loud hiss when disturbed.7,14 There is anecdotal information that suggests that these snakes have strangled humans to death,4 but this has not yet been confirmed.2 However, there are accounts of Green Anacondas attempting predatory strikes on humans.2,23,24 Although their bite is not venomous, their curved teeth can still tare through flesh and muscles.2 Also, their mouths contains bacteria that can infect a wound.6 There are records of White Caimans (Caiman crocodilus)2 and jaguars (Panthera onca)25 preying upon adults of Eunectes murinus. Tegus (Tupinambis cryptus),2 Crested Caracaras (Polyborus plancus), ocelots,21 foxes,21 storks, raptors, and herons have been confirmed to prey upon juveniles.6 Green Anacondas are parasitized by ticks, leeches, and a variety of parasitic worms.2

“Enormous water snakes, in shape resembling the boas, are unfortunately very common, and are dangerous to the Indians who bathe. We saw them almost from the first day we embarked, swimming by the side of our canoe; they were at most twelve or fourteen feet long.”

Alexander von Humboldt, German geographer, naturalist, and explorer, 1885.

The breeding season in Eunectes murinus takes place during the dry season in Venezuela and Trinidad, both in and out of the water.2,4 In captivity, both males and females attain sexual maturity at around four years of age.26 During copulation, the anal hooks of the male, which generally have no other function, are used to scratch the sides of the female.4 Copulation may last anywhere from half an hour27 up to 20 days.4 This species has a polyandrous mating system. Multiple males (up to 13)2 attempt to simultaneously mate with a single female; thus forming a “ball” of snakes that may last for an average of 18 days (range 2–46 days).2,7 Females may cannibalize males after mating,28,29 a strategy that may help them alleviate the fasting during gestation.2 After an incubation period of 6–7 months,4,30 females “give birth” (the eggs hatch within the mother)27 to 18–82 (usually 20–40)6 young26,30 that measure 36–85 cm in total length.1 Aborted eggs, along with fetal membranes, may be devoured by the parturient female.31 This species is capable of facultative parthenogenesis, meaning embryos can develop from unfertilized eggs.7,32 Litters resulting from parthenogenesis are smaller (2–8 neonates), with higher mortality rates, and are all female.32,33 Captive individuals may live up to 31.8 years.34,35 In the wild, one individual was recaptured after 13 years and was estimated to be 20 years old.36

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..37 Eunectes murinus is listed in this category because it is widely distributed, occurs in numerous protected areas, has relatively large and stable populations, and is facing no major immediate extinction threats.20 However, this species has been the subject of intense harvesting for centuries. To this day, live individuals are marketed as pets and their raw skins shipped to tanneries around the world,38,39 which is why the species is included in Appendix II of CITES.38,40 Local residents in Brazil and Venezuela kill individuals of E. murinus to remove the fat bodies of the snake and use them as treatment against inflammatory diseases and infections.6,41 Most other villagers simply kill these snakes out of fear or as a “preventive” measure.20 There is a record of a fisherman pouring fuel and setting fire to a complete ball of breeding anacondas.6 In Venezuela, human management of water is negatively affecting populations in the savanna ecosystem by increasing the likelihood of individuals dying from desiccation.2 Finally, Green Anacondas routinely show up drowned in fish nets8,14 or dead on the road due to vehicular traffic.11

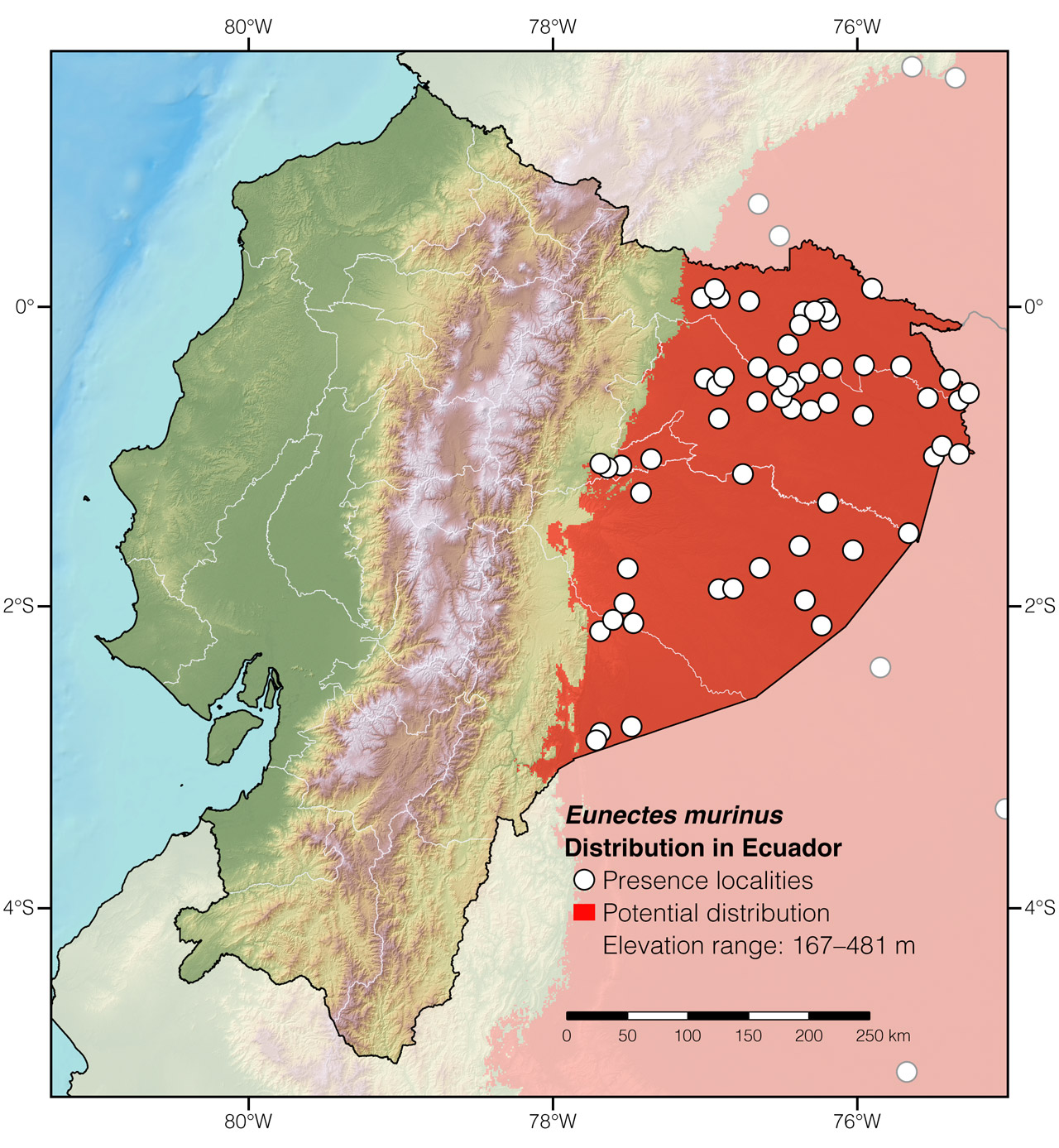

Distribution: Eunectes murinus is native to an estimated 623,511 km2 area throughout the tropical lowlands of South America east of the Andes.12 The species occurs throughout the Amazon basin in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.12 It is also present in the seasonally flooded Llanos grasslands of Venezuela and Colombia, the Cerrado in Brazil and Paraguay, and in Trinidad Island. In Ecuador, the species has been recorded at elevations between 167 and 481 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Eunectes murinus in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Eunectes comes from the Greek words eu (=good) and nektes (=swimmer).42 The specific epithet murinus is a Latin word meaning “mouse gray.”42 It probably refers to the alcohol-preserved color of the holotype.43

See it in the wild: Despite their enormous size, Green Anacondas are difficult to find in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Their secretive habits in a structurally complex ecosystem where the water is usually murky and full of vegetation make finding these animals a real challenge.13 It appears the best way of locating these large serpents is to use a dugout canoe to patrol the edge of black-water lagoons and slow-moving rivers during a sunny day or at night, especially along areas having abundant aquatic vegetation. In Ecuador, the quintessential Green Anaconda sighting ground is Laguna Grande in Cuyabeno Reserve. Other areas where the species is spotted relatively frequently are lagoons Jatuncocha and Añangu in Yasuní National Park.

Special thanks to Tin Tin and Claire Holmes for symbolically adopting the Green Anaconda and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/PVMS8384

Literature cited:

- Belluomini HE, Maranho-Nina AF, Hoge AR (1959) Contribução à biologia do gênero Eunectes Wagler, 1830. Memórias do Instituto Butantan 29: 165–174.

- Rivas JA (2000) The life history of the Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus), with emphasis of its reproductive biology. PhD thesis, The University of Tennessee, 155 pp.

- Minton SA, Minton MR (1973) Giant reptiles. Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York, 345 pp.

- Mole RR (1924) The Trinidad Snakes. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 1: 235–278.

- Pope CH (1961) The giant snakes. Knopf, New York, 290 pp.

- Barrio-Amorós CL, Manrique R (2008) Observations on the natural history of the Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus Linnaeus, 1758) in the Venezuelan Llanos: an ecotourism perspective. Iguana 15: 93–101.

- Murphy JC, Downie R, Smith JM, Livingstone S, Mohammed R, Lehtinen RM, Eyre M, Sewlal JN, Noriega N, Casper GS, Anton T, Rutherford MG, Braswell AL, Jowers MJ (2018) A field guide to the amphibians & reptiles of Trinidad and Tobago. Trinidad and Tobago Naturalist’s Club, Port of Spain, 336 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Greene BT (1997) Snakes: the evolution of mystery in nature. University of California Press, San Diego, 351 pp.

- Murphy JC, Henderson RW (1997) Tales of giant snakes: a historical natural history of anacondas and pythons. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, 221 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Rivas JA, Muñoz MC, Thorbjarnarson JB, Burghardt GM, Holmstrom WF, Calle PP (2007) Natural history of the Green Anacondas in the Venezuelan llanos. In: Henderson RW, Powell R (Eds) Biology of the boas and pythons. Eagle Mountain Publishing, Eagle Mountain, 129–138.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Sanchez JL, Starace F, Ineich I (2017) First verified case of arboreal behaviour in the green anaconda, Eunectes murinus (Linnaeus, 1758) (Serpentes, Boidae). Bulletin de la Societé Herpétologique de France 178: 106–112.

- Rivas JA, Molina CR, Corey SJ, Burghardt GM (2016) Natural history of neonatal Green Anacondas (Eunectes murinus): a chip off the old block. Copeia 104: 402–410.

- De la Quintana P, Rivas JA, Valdivia F, Pacheco LF (2018) Eunectes murinus (Green Anconda): dry season home range. Herpetological Review 49: 546–547.

- Thomas O, Allain SJR (2021) A review of prey taken by anacondas (Squamata: Boidae: Eunectes). Reptiles & Amphibians 28: 329–334.

- Miranda EBP, Ribeiro RP, Strüssmann C (2016) The ecology of human-anaconda conflict: a study using internet videos. Tropical Conservation Science 9: 43–77.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Infante-Rivero E, Natera-Mumaw M, Marcano A (2010) Extension of the distribution of Eunectes murinus (Linnaeus, 1758) and Helicops angulatus (Linnaeus, 1758) in Venezuela, with notes on ophiophagia. Herpetotropicos 4: 39.

- Rivas JA (1998) Predatory attack of a Green Anaconda (Eunectes murinus) on an adult human. Herpetological Natural History 6: 158–160.

- Murphy JC (1997) Amphibians and reptiles of Trinidad and Tobago. Krieger, Malabar, 245 pp.

- Photo by Jorge Barragán.

- Holmstrom WF (1982) Eunectes (anacondas): maturation. Herpetological Review 13: 126.

- Holmstrom WF (1980) Observation on the reproduction of the common anaconda, Eunectes murinus at the New York Zoological Park. Herpetological Review 11: 32–33.

- Photo by Luciano Candisani.

- Rivas JA, Owens RY (2000) Eunectes murinus (Green Anaconda): cannibalism. Herpetological Review 31: 45–46.

- Belluomini HE, Hoge AR (1957) Operaçao cesariana realizada em Eunectes murinus (Linnaeus 1758) (Serpentes). Memórias do Instituto Butantan 28: 187–194.

- Neill WT, Allen R (1959) Parturient anaconda, Eunectes gigas Latreille, eating own abortive eggs and fetal membranes. Quarterly Journal of the Florida Academy of Sciences 25: 73–75.

- Shibata H, Sakata S, Hirano Y, Nitasaka E, Sakabe A (2017) Facultative parthenogenesis validated by DNA analyses in the green anaconda (Eunectes murinus). PLoS ONE 12: e0189654. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0189654

- O’Shea M, Slater S, Scott R, Smith SA, McDonald K, Lawrence B, Kubiak M (2016) Eunectes murinus (Green Anaconda): reproduction and facultative parthenogenesis. Herpetological Review 47: 73.

- Slavens F, Slavens K (2022) Longevity and breeding of reptiles and amphibians in captivity. Available from: www.pondturtle.com

- Shine R (1992) Snakes. In: Cogger HG, Zweifel RG (Eds) Reptiles and amphibians. Smithmark Publishers, New York, 174–211.

- Rivas JA, Corey SJ (2008) Eunectes murinus (Green Anaconda): longevity. Herpetological Review 39: 469.

- Calderón M, Ortega A, Scott N, Cacciali P, Nogueira CdC, Gagliardi G, Catenazzi A, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Hoogmoed MS, Schargel W, Rivas G, Murphy J (2014) Eunectes murinus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T44580041A44580052.en

- Rivas JA (2007) Conservation of Green Anacondas: how tylenol conservation and macroeconomics threaten the survival of the World’s largest snake. Iguana 14: 76–85.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- UNEP-WCMC (2014) Review of species selected on the basis of the analysis of 2014 CITES export quotas. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, 66 pp.

- Romeu da Nóbrega Alves RR, Alves Pereira Filho G, Cordeiro Delima YC (2007) Snakes used in ethnomedicine in Northeast Brazil. Environment Development and Sustainability 9: 455–464. DOI: 10.1007/s10668-006-9031-x

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Linnaeus C (1758) Systema Naturae. Editio Decima, Reformata. Impensis Laurentii Salvii, Stockholm, 824 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Eunectes murinus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | El Paujil | Informativo 7/24 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Online multimedia |

| Colombia | Caquetá | San Vicente del Caguán | Cortes-Ávila & Toledo 2013 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Head of Río Putumayo | MVZ 33699 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Boy | MLS 55 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | MCZ 42354 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Ashuara Village | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Parroquia Macuma | GAD Parroquia Macuma 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Puerto Morona | Patricio Estrella, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Macuma | AMNH 107660 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Morona, near San Jose de Morona | MAE Morona |

| Ecuador | Napo | Boca del Río Arajuno | Diego Piñán, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Laguna Paikawe | Diego Piñán, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Shiripuno, near Gareno | Hidrobo Unda 2012 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Estación Científica Yasuní | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Estación Científica Yasuní, 15 km E of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Guiyero | Almendáriz 2011 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Laguna Jatuncocha | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Mandaripanga Camp | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Rocafuerte | USNM 204102 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini, near vía Auca | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini, near Apaica | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Sector El Carmen | MAAE Orellana |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bameno | Photo by Marcelo Behigua |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chapintza | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Copataza (Achuar) | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Curaray Lodge | Photo by Rodrigo Jipa |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Loracachi | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Conambo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Cononaco | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Toñampare | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Adhán Payahüaje | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Ballesteros | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Boca del Río Zábalo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Isla Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lagartococha | Usma et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Pañacocha | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | This work |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Parque La Perla | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Piranha Ecolodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente Río Cuyabeno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto El Carmen | MAE Napo |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Providencia | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Aguarico, 5 km from Peruvian border | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Cuyabeno | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Zábalo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | MHNG 2445.032 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Thomas et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Zancudococha | Online multimedia |

| Perú | Loreto | Bloque 123 | MINEM Peru |

| Perú | Loreto | Provincia Alto Amazonas | Aquino Yarihuaman 2013 |

| Perú | Loreto | Redondococha | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Santa María de Angoteros | TCWC 42063 |

| Perú | Loreto | Shiviyacu, near Río Tigre | Valqui Schult 2015 |