Published May 24, 2022. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Gibba Turtle (Mesoclemmys gibba)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Chelidae | Mesoclemmys gibba

English common names: Gibba Turtle, Humpback Toadhead-Turtle.

Spanish common names: Tortuga hedionda, asna charapa.

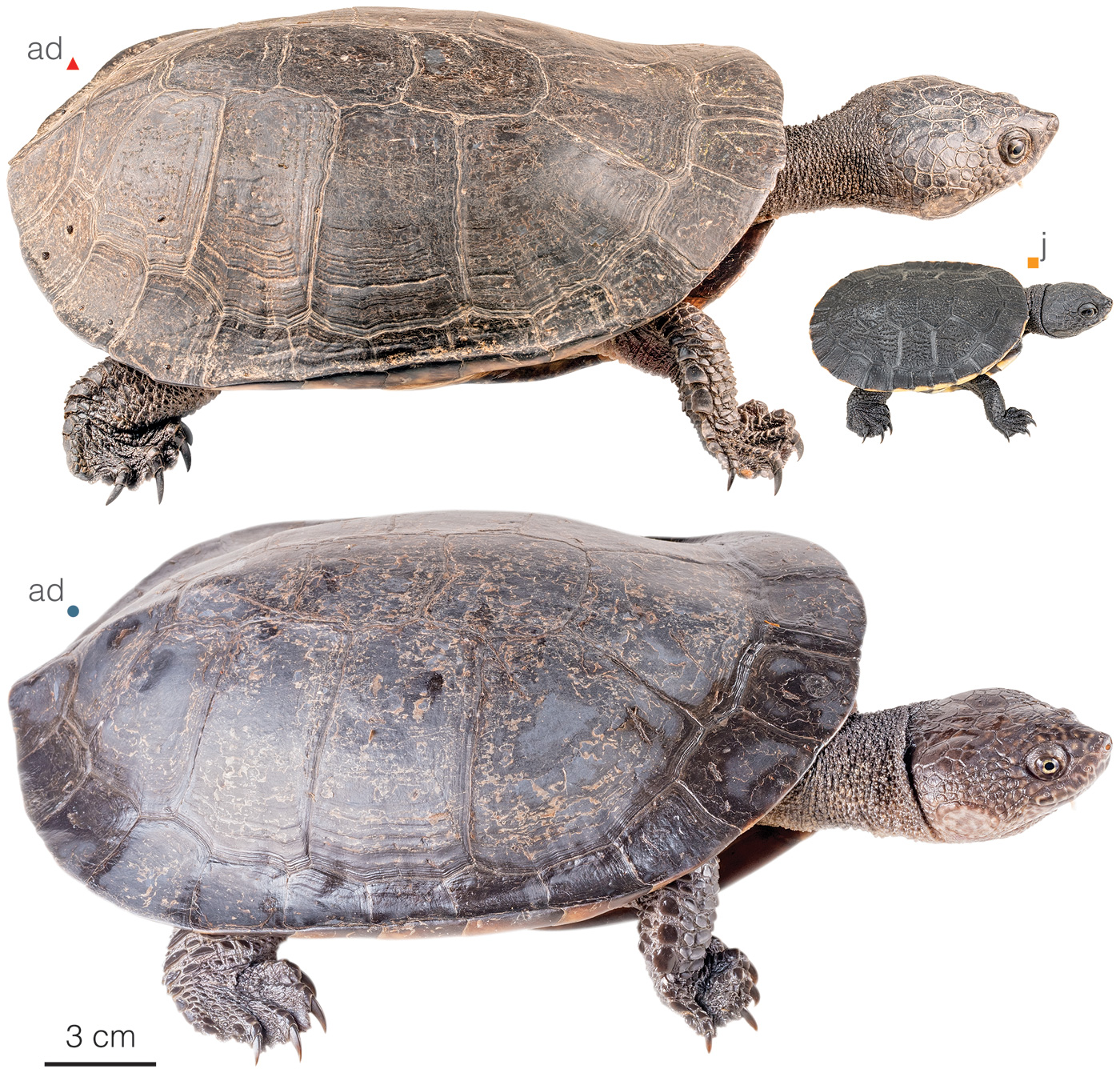

Recognition: ♂♂ 20.0 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 23.3 cmMaximum straight length of the carapace..1 The Gibba Turtle (Mesoclemmys gibba) can be identified from other Amazonian freshwater turtles by having a laterally retracting neck, head covered by small scales, and a broad and smooth carapace lacking prominent ridges and keels.2,3 In Amazonian Ecuador, M. gibba is most likely to be confused with M. raniceps,4 from which it differs by having a narrower (less than 26% of carapace length) head with no wide areas of light pigmentation, but many small, faint, paler brown spots on a grayish background.5–7 It may also be confused with Phrynops geoffroanus, a turtle characterized by having a narrower head with a distinct black postocular stripe.2,3 Turtles of the genus Podocnemis differ from those of the genus Mesoclemmys by having the dorsum of the head covered by large broad scales.2 Males of M. gibba are smaller than females and have longer and thicker tails.2

Figure 1: Adult individual of Mesoclemmys gibba from Palmarí Reserve, Amazonas state, Brazil.

Natural history: UncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months. and often overlooked due to the species’ preference for muddy-bottomed waters.8,9 Mesoclemmys gibba is an aquatic turtle that inhabits slow-moving bodies of water in well-preserved lowland rainforests in white and black-water drainage systems.9,10 Gibba Turtles are nocturnal8 and spend almost the entirety of their life in small forest streams,8 rivers,8,11 forest ponds,3,7 drainage ditches,8 marshes,3 and morichales (palm groves of Mauritia flexuosa).8,12 Occasionally, individuals may be seen basking in the early morning or late afternoon.8 Gibba Turtles are omnivores. In the wild, they feed on plant (leaves, grasses, stems, fruits, flowers, and bark) as well as on animal (insects, crustaceans, and fish) matter.4,13 In captivity, they consume fish, meat, worms, insects, crustaceans, tadpoles, newborn mice, dog food, and plant material.4,8,14 When threatened, individuals of M. gibba produce a fetid smell; hence the local name “tortuga hedionda” (=stinking turtle) in Spanish.4 There are records of anacondas (Eunectes murinus) preying upon individuals of this species.15 The breeding season in this species occurs at the end of the rainiest months.4 Females lay clutches of 2–4 eggs5 that measure 42.0–44.5 x 29.5–32.0 mm and weigh 22.5–28.0 g.8 These are laid among roots, under logs, beneath rotten leaves,12 inside termite mounds,12 or in 10–15 cm nests14 excavated in soft soil along embankments of streams.4,8 The eggs hatch after an incubation period of 116–270 days (~4–9 months).5,8,14 Hatchlings measure 4.3–4.8 cm in straight carapace length.8

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..16,17 Mesoclemmys gibba is included in this category given its wide distribution throughout the Amazon basin, especially over areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation. Therefore, the species is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. Adults of M. gibba are under no widespread pressure from harvesting, probably due to their rarity and undesirable smell.2 However, some local communities eat Gibba Turtles or sell them whenever found or when caught incidentally by hook and line.8,18 However, it seems like M. gibba requires pristine forests to survive; thus, some populations might be declining due to habitat loss and degradation.

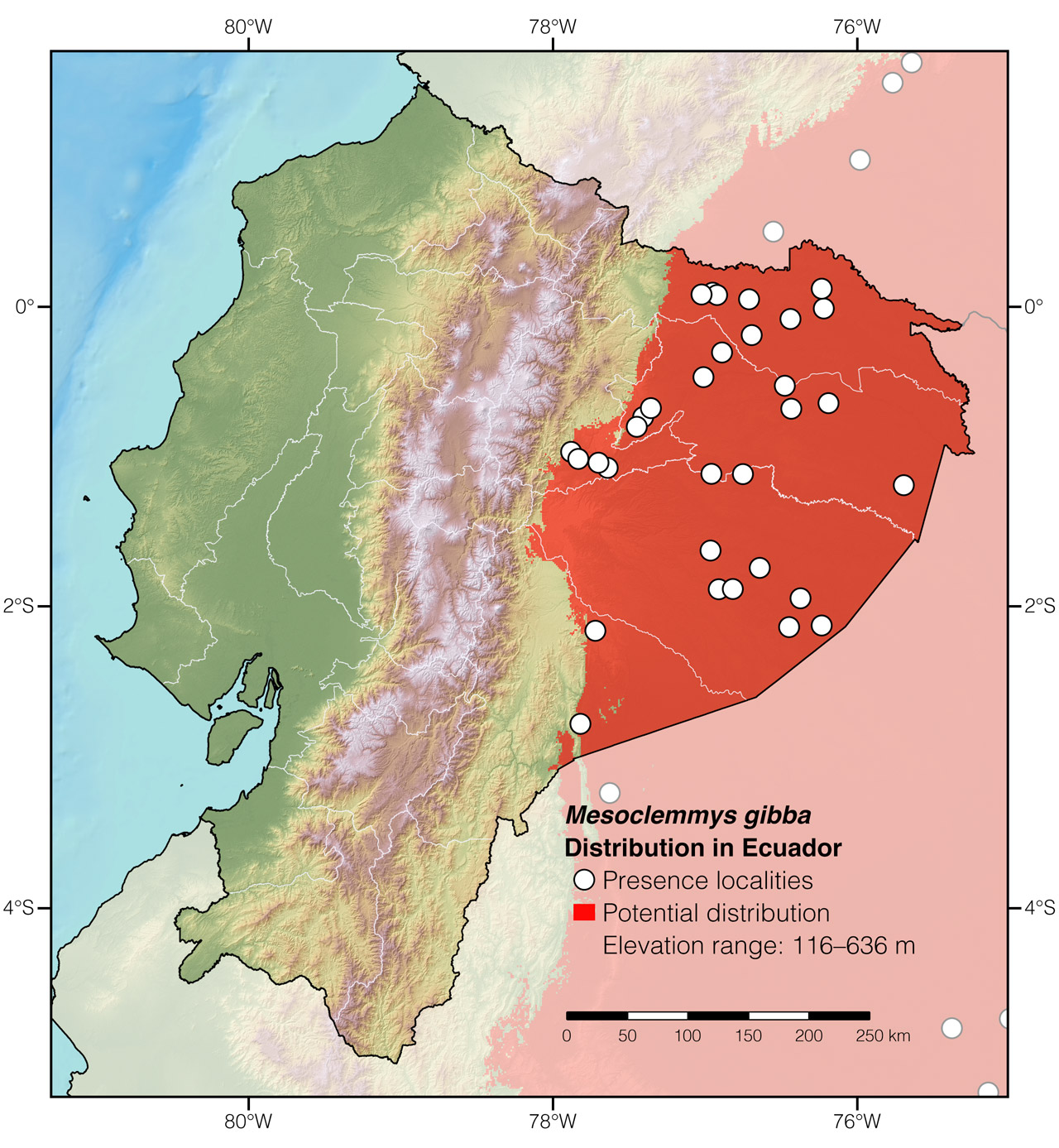

Distribution: Mesoclemmys gibba is native to an estimated 3,993,262 km2 in the Amazon basin of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela.1 The species occurs in the Amazon and Orinoco drainage systems as well as in Trinidad Island.19 In Ecuador, M. gibba has been recorded at elevations between 116 and 636 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Mesoclemmys gibba in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Mesoclemmys comes from the Greek words mesos (meaning “middle”) and klemmys (meaning “tortoise”).20 At the time of description,21 turtles of this genus were believed to be an intermediate form between Hydraspis and Platemys.22 The specific epithet gibba is a Latin word meaning “humpbacked.” It refers to the shape of the carapace in this turtle.20

See it in the wild: Gibba Turtles are rarely encountered in the wild in Ecuador. This species has been found in Yasuní Scientific Station, Tiputini Biodiversity Station, and Jatun Sacha Biological Station, but only at a rate of about 1–2 individuals per year. These turtles are most easily found by walking along slow-moving bodies of water right after sunset.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Sebastián Di DoménicobAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Gibba Turtle (Mesoclemmys gibba). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/HIEF4630

Literature cited:

- Rhodin AGJ, Iverson JB, Bour R, Fritz U, Georges A, Shaffer HB, van Dijk PP (2021) Turtles of the world: annotated checklist and atlas of taxonomy, synonymy, distribution, and conservation status. Chelonian Research Monographs 8: 1–472. DOI: 10.3854/crm.8.checklist.atlas.v9.2021

- Rueda-Almonacid JV, Carr JL, Mittermeier RA, Rodríguez-Mahecha JV, Mast RB, Vogt RC, Rhodin AGJ, de la Ossa-Velásquez J, Rueda JN, Mittermeier CG (2007) Las tortugas y los cocodrilianos de los países andinos del trópico. Conservación Internacional, Bogotá, 538 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Ferrara CR, Fagundes CK, Morcatty TQ, Vogt RC (2017) Quelônios Amazônicos: guia de identificação e distribuição. Wildlife Conservation Society, Manaus, 180 pp.

- Cunha FAG, Fernandes T, Franco J, Vogt RC (2019) Reproductive biology and hatchling morphology of the Amazon Toad-headed Turtle (Mesoclemmys raniceps) (Testudines: Chelidae), with notes on species morphology and taxonomy of the Mesoclemmys group. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 18: 1–16. DOI: 10.2744/CCB-1271.1

- Molina FB, Machado FA, Zaher H (2012) Taxonomic validity of Mesoclemmys heliostemma (McCord, Joseph-Ouni & Lamar, 2001) (Testudines, Chelidae) inferred from morphological analysis. Zootaxa 3575: 63–77. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3575.1.4

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Mittermeier RA, Rhodin AGJ, Medem F, Soini P, Hoogmoed M, Carrillo de Espinosa N (1978) Distribution of the South American chelid turtle Phrynops gibbus, with observations on habitat and reproduction. Herpetologica 34: 94–100.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF (2006) Turtles of the Tiputini Biodiversity Station with remarks on the diversity and distribution of the Testudines from Ecuador. Biota Neotropica 6: 1–16. DOI: 10.1590/S1676-06032006000100011

- Kearney P (1972) Nocturtles of Trinidad. International Turtle and Tortoise Society Journal 6: 10–11.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA (2012) Mesoclemmys gibba. In: Páez VP, Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Castaño-Mora OV, Bock BC (Eds) Biología y conservación de las tortugas continentales de Colombia. Serie Editorial Recursos Hidrobiológicos y Pesqueros Continentales de Colombia, Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt (IAvH), Bogotá, 254–256.

- de Oliveira Ferronato B, Piña CI, Cochachez Molina F, Espinosa RA, Morales VR (2013) Feeding habits of Amazonian freshwater turtles (Podocnemididae and Chelidae) from Peru. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 12: 119–126. DOI: 10.2744/CCB-0938.1

- Métrailler S (2006) Keeping and breeding of Mesoclemmys gibba (Schweigger, 1812). In: Artner H, Farkas B, loehr V (Eds) Proceedings of the International Turtle & Tortoise Symposium. Edition Chimaira, Vienna, 338–341.

- Thomas O, Allain SJR (2021) A review of prey taken by anacondas (Squamata: Boidae: Eunectes). Reptiles & Amphibians 28: 329–334.

- Morales-Betancourt MA, Lasso CA, Páez VP, Bock BC (2005) Libro rojo de reptiles de Colombia. Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Bogotá, 257 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Ferronato BO, Morales VM (2012) Biology and conservation of the freshwater turtles and tortoises of Peru. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 19: 103–116.

- Auguste RJ, Deo R, Ali Z (2019) Two additional site records of the elusive Gibba Turtle Mesoclemmys gibba (Schweigger 1812) fromTrinidad, W.I. Living World, Journal of the Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club 2019: 43–44.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Mesoclemmys gibba in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | UAM-R-0412 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Morelia | MLS 149 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Caquetá | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cantón Morona | MAE Morona 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Estación Biológica Jatun Sacha | Vigle 2008 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Misahuallí | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Tena | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Joya de los Sachas | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Napo Wildlife Center | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Huataraco | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Nashiño | Pérez Peña et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Pucuno | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Suno | Mittermeier et al. 1978 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tigüino | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Conambo | Mittermeier et al. 1978 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindoyacu | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tributary of the Río Conambo | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación Amazonas OCP | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Parque Ecologico Nueva Loja | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sansahuari | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa, 8 km NW of | Cisneros-Heredia 2006 |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Loreto | Maipuco | Mittermeier et al. 1978 |

| Perú | Loreto | Monte Rico | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Loreto | Reserva Nacional Pacaya Samiria | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Morona | Rhodin et al. 2021 |

| Perú | Loreto | San José de Saramuro | Rhodin et al. 2021 |