Published October 10, 2019. Updated December 11, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Iguanidae | Amblyrhynchus cristatus

English common name: Marine Iguana.

Spanish common name: Iguana marina.

Recognition: ♂♂ 133 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=54 cm. ♀♀ 78.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1 Amblyrhynchus cristatus is one of four species of iguanas occurring on the Galápagos Islands. The other three are the land iguanas of the genus Conolophus. The Marine Iguana differs from all of them by having a blunt snout, a laterally flattened tail adapted to swimming, and a distinct, usually blackish, background color (Fig. 1). Adult males differ from females by being larger, having a more contrasting coloration, and a raised middorsal crest. Marine Iguanas from different islands also vary in size and coloration. Iguanas living on large islands are usually bigger, whereas those on islands smaller than 25 km2 are usually dwarf. Throughout most of the archipelago, the iguanas have a blackish color, but in the southern Islands (Española and Floreana) dominant males acquire a striking “Christmas” coloration, boasting bright red with green and/or blue legs during the breeding season (Fig. 1), although the cause for this unique color change remains enigmatic.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Amblyrhynchus cristatus from Galápagos, Ecuador: Santa Cruz Island (); Española Island (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Amblyrhynchus cristatus is a diurnal iguana that lives in large aggregations (up to 8,000 individuals/km coastline)2 along coastal volcanic outcrops, cliffs up to 50 m high, mangroves, and sandy beaches.3 It is a mostly terrestrial species that spends nearly 5% of its time in the sea, grazing seaweed off the surface of rocks.4 No other lizard in the world forages at sea. Marine Iguanas feed almost exclusively on algae, but may also ingest beach plants,5 octopuses, crustaceans, grasshoppers, cockroaches, fish carrion, and even sea lion feces and afterbirth.6 Hatchlings feed on the adults’ feces to obtain the gut microorganisms needed to digest algae.7 Iguanas heavier than 1.8 kg usually dive 15 m down and for up to 20 minutes to feed,2,4 whereas individuals lighter than 1.2–1.4 kg typically forage on exposed intertidal rocks.3,8 After a dive, they commute to their preferred resting sites (rocks with interspersed crevices or bushes)9 where they “sneeze” excess salt.3

Marine Iguanas spend the first hours after sunrise basking in the sun,3 and usually enter the sea between 7:30 and 8:00 am.3 On hot afternoons, some individuals seek the shade of reef crevices, large boulders, mangroves, and shrubs,3 while others remain in the open. Just before sunset, they retreat into these same hideouts, but they can also spend the night exposed on the reef3 or up on mangrove branches.10 Occasionally, especially during the dry and cool season (June–November), they form sleeping aggregations of dozens of individuals. They sleep closely in contact with each other probably as an attempt to maintain warmth during the night. Marine Iguanas are preyed upon by introduced species (including pigs, dogs, cats, and rats) as well as by native species (for example, hawks, owls, herons, gulls, the snakes Pseudalsophis biserialis, P. dorsalis, and P. occidentalis, hawkfish, and crabs).2,9–13 When threatened, small iguanas run into crevices.14

The beginning of the breeding season varies from island to island,2,7,15 but generally takes place between December and January3 over a period of slightly over three weeks.8 Male Marine Iguanas defend 1.2–38.8 m2 display territories by bobbing their heads8 or fighting head-to-head with intruders.2,8 Between head pushing duels, the males bite each other and at times seriously wound each other.8 Usually only the largest males16 monopolize most of the matings, copulating with as many as 45 females per season.8 Some smaller, non-territorial “sneaky” males that are similar in size to females attempt to copulate inside territories when territorial males are absent.16 They increase their chances of fertilizing females by preparing in advance with pre-copulatory ejaculation.17 Some males appear unable to distinguish the sex of female-sized individuals, with which they attempt to copulate.16 Females mate only once per season,8 preferentially with the largest territorial males.16 Copulations last 2–20 minutes.8 About a month later, females, which compete fiercely over nesting sites,17 dig 30–40 cm holes in sandy soil18 and lay 1–6 eggs11 that take 89–120 days (~3–4 months) to hatch.8 Mockingbirds prey upon eggs.18 Hybrids between the Marine Iguana and the Galápagos Land-Iguana (Conolophus subcristatus) exist on Plaza Sur Island.19 The estimated maximum lifespan of members of A. cristatus is 30 years.20

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future..21 Amblyrhynchus cristatus is listed in this category despite having high population densities,2,22 because the species’ extent of occurrence is estimated to be less than 500 km2, it experiences periodic population declines of up to 85% mortality due to El Niño events, and is threatened by pollution and invasive predators.20 There are also multiple genetically distinct populations, some of which are extremely small in size (for example, the population on northeastern San Cristóbal).23,24 For most of these, there is a lack of solid information about population sizes, which makes them vulnerable to rapid enigmatic declines which may go unnoticed.

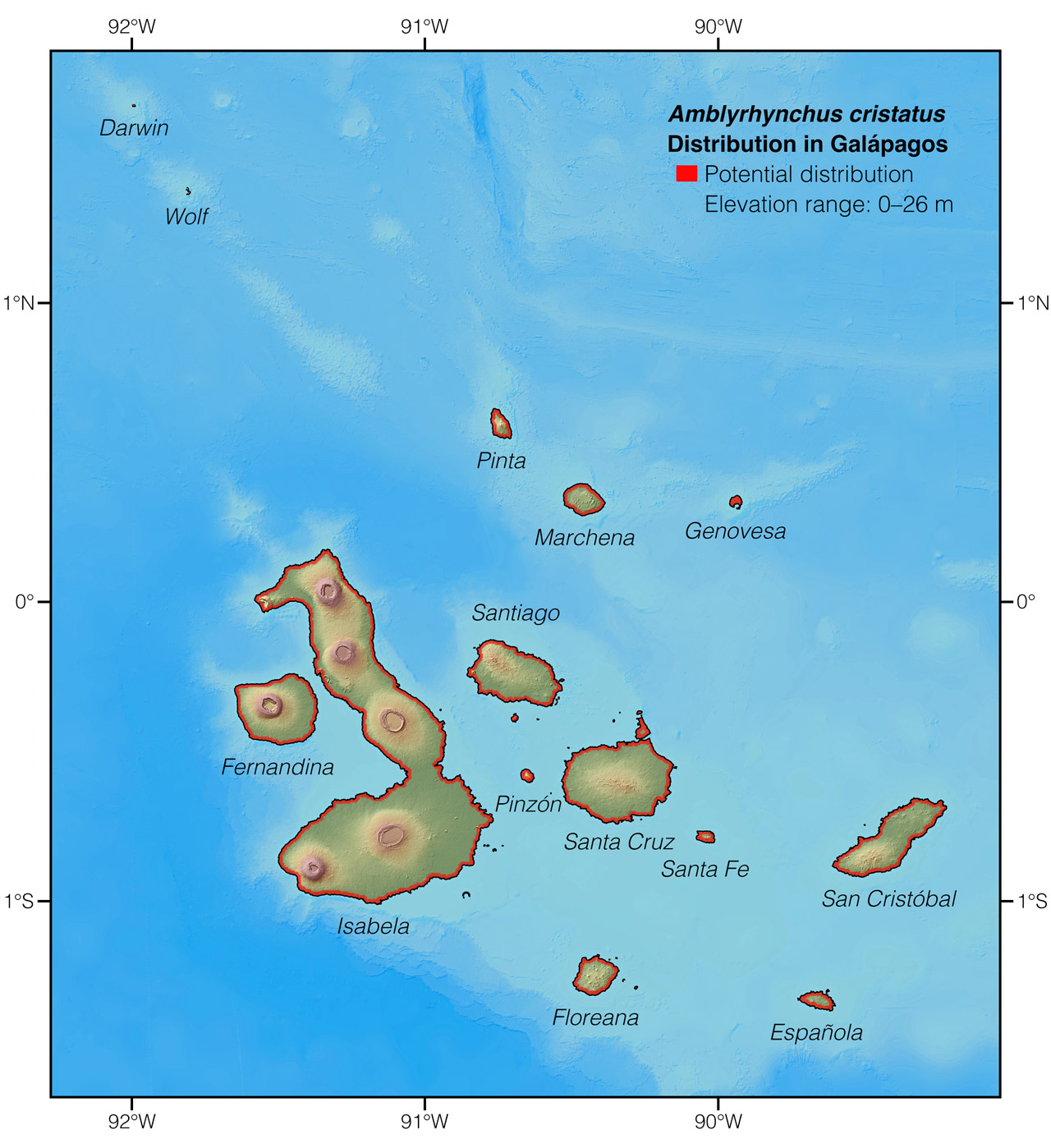

Distribution: Amblyrhynchus cristatus is endemic to an estimated 275 km2 area in Galápagos, Ecuador (Fig. 2). Marine Iguanas occur on coastal areas of all major islands and most of their surrounding islets. There is one unpublished photographic record of a Marine Iguana on Isla de la Plata, ~24 km off the coast of mainland Ecuador. The arrival of this single individual occurred on February 2014 and is though to be the result of waif dispersal.

Figure 2: Distribution of Amblyrhynchus cristatus in Galápagos.

Etymology: The generic name Amblyrhynchus comes from the Greek words amblys (=obtuse) and rhynchos (=snout),25 and refers to the blunt snout. The specific epithet cristatus comes from the Latin word crista (=ridge) and the suffix -atus (=provided with),25 and refers to the raised crest.14

“The black lava rocks on the beach are frequented by large, disgusting clumsy lizards. They are as black as the porous rocks over which they crawl and seek their prey from the sea. Somebody calls them ‘imps of darkness’…”

Charles Darwin, 1835.26

See it in the wild: Although Marine Iguanas can be seen year-round with complete certainty on almost any rocky beach in Galápagos, the best time to photograph them is during the peak of the breeding season (December–January), when males are strikingly colored.

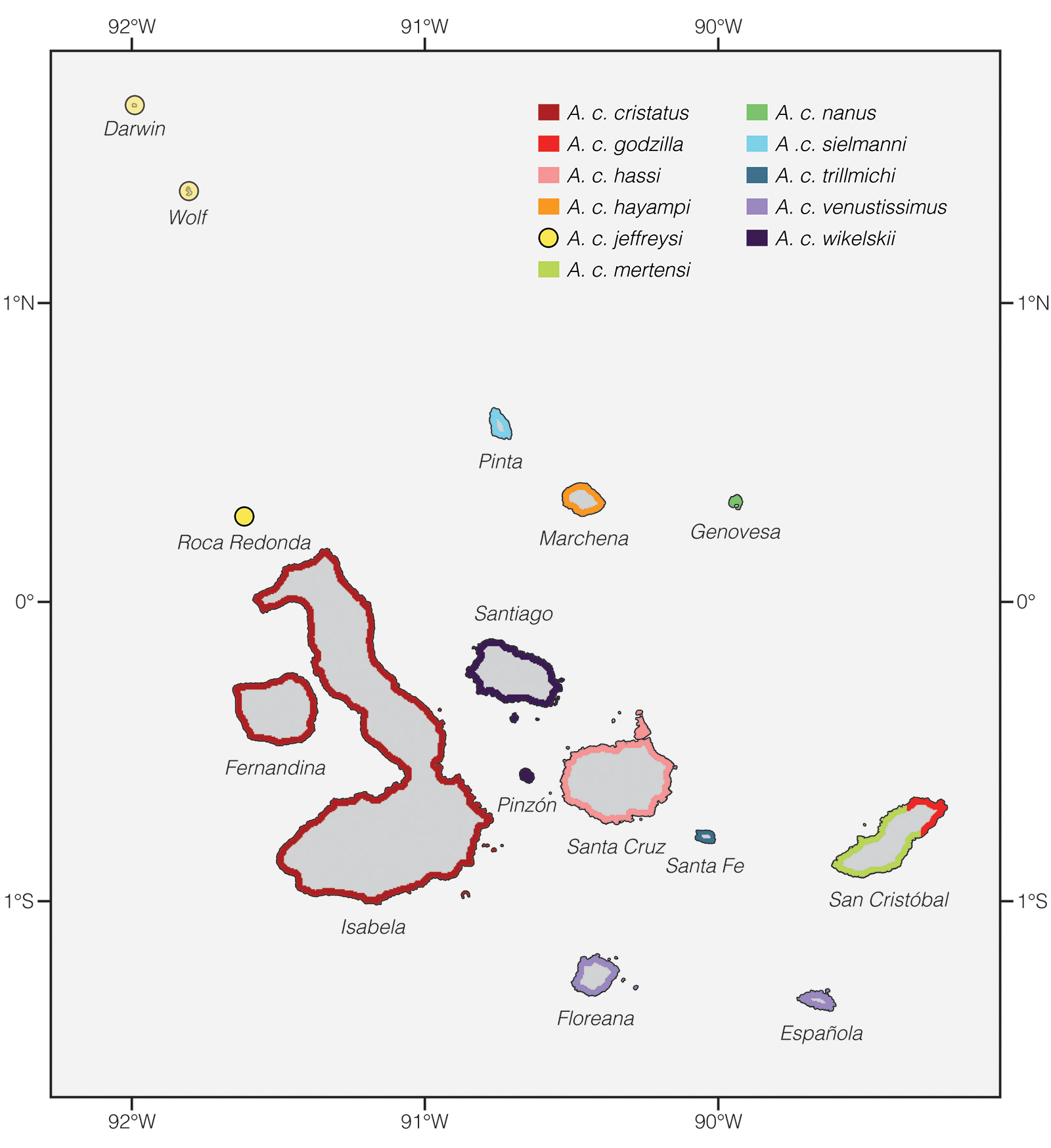

Subspecies of the Marine Iguana. The most recent study23 about the classification of the Marine Iguana considers Amblyrhynchus cristatus to be a single species with eleven population clusters categorized as subspecies (Fig. 3). Iguanas belonging to each subspecies differ from each other in size, shape, coloration, genetics, and conservation status.

Figure 3. Distribution of the Marine Iguana subspecies according to Miralles et al. (2017).23

Special thanks to Theresa Bouchard and Sarah Hollis for symbolically adopting the Marine Iguana and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Dustin Rubenstein, Amy MacLeod, and Miguel Vences.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,cAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2023) Marine Iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/XNIC9736

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: Life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp.

- Laurie WA (1989) Effects of the 1982–83 El Niño-Southern Oscillation event on marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus, Bell, 1825) populations in the Galápagos Islands. In: Glynn P (Ed) Global ecological consequences of the 1982–83 El Niño-Southern Oscillation. Elsevier, New York, 121–141. DOI: 10.1016/S0422-9894(08)70041-2

- Carpenter CC (1966) The marine iguana of the Galápagos Islands, its behavior and physiology. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 34: 329–376.

- Trillmich KGK, Trillmich F (1986) Foraging strategies of the Marine Iguana, Amblyrhynchus cristatus. Behavior, Ecology and Sociobiology 18: 259–266. DOI: 10.1007/BF00300002

- Vitousek MN, Rubenstein DR, Wikelski M (2007) The evolution of foraging behavior in the Galápagos marine iguana: natural and sexual selection on body size drives ecological, morphological, and behavioral specialization. In: Reilly SM, McBrayer LD, Miles DB (Eds) Lizard ecology: the evolutionary consequences of foraging mode. Cambridge University Press, New York, 491–507. DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511752438.018

- Wikelski M, Wrege PH (2000) Niche expansion, body size, and survival in Galápagos marine iguanas. Oecologia 124: 107–115. DOI: 10.1007/s004420050030

- Rubenstein DR, Wikelski M (2003) Seasonal changes in food quality: a proximate cue for reproductive timing in marine iguanas. Ecology 84: 3013–3023. DOI: 10.1890/02-0354

- Trillmich KGK (1983) The mating system of the marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). Zeitschrift Für Tierpsychologie 63: 141–172. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1983.tb00084.x

- Wikelski M, Trillmich F (1994) Foraging strategies of the Galápagos marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus): adapting behavioral rules to ontogenetic size change. Behaviour 128: 255–279. DOI: 10.1163/156853994X00280

- Eibl-Eibesfeldt I (1984) The large iguanas of the Galápagos Islands. In: Perry R (Ed) Key environments: Galápagos. Pergamon Press, Oxford, 157–173.

- Laurie WA, Brown D (1990) Population biology of marine iguanas (Amblyrhynchus cristatus). II. Changes in annual survival rates and the effects of size, sex, age and fecundity in a population crash. Journal of Animal Ecology 59: 529–544.

- Laurie WA (1983) Marine iguanas in Galápagos. Oryx 17: 18–25.

- Christian EJ (2017) Demography and conservation of the Floreana racer (Pseudalsophis biserialis biserialis) on Gardner-by-Floreana and Champion islets, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. PhD thesis, Auckland, New Zealand, Massey University.

- Van Denburgh J, Slevin JR (1913) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. IX. The Galapagoan lizards of the genus Tropidurus with notes on iguanas of the genera Conolophus and Amblyrhynchus. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 2: 132–202.

- Partecke J, von Haeseler A, Wikelski M (2002) Territory establishment in lekking marine iguanas, Amblyrhynchus cristatus: support for the hotshot mechanism. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 51: 579–587. DOI: 10.1007/s00265-002-0469-z

- Wikelski M, Carbone C, Trillmich F (1996) Lekking in marine iguanas: female grouping and male reproductive strategies. Animal Behavior 52: 581–596. DOI: 10.1006/anbe.1996.0199

- Wikelski M, Bäurle S (1996) Pre-copulatory ejaculation solves time constraints during copulations in marine iguanas. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences 263: 439–444. DOI: 10.1098/rspb.1996.0066

- Eibl-Eibesfeldt I (1966) Das Verteidigen der Eiablageplätze bei der Hood-Meerechse. Zeitschrift für Tierpsychologie 23: 627–631. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1966.tb01617.x

- Rassmann K, Trillmich F, Tautz D (1997) Hybridization between the Galápagos land and marine iguana (Conolophus subcristatus and Amblyrhynchus cristatus) on Plaza Sur. Journal of Zoology 242: 729–739. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-7998.1997.tb05822.x

- Berry RJ (1984) Evolution in the Galápagos Islands. Academic Press, London, 270 pp.

- MacLeod A, Nelson KN, Grant TD (2020) Amblyrhynchus cristatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T1086A177552193.en

- Bowman RI, Berson M, Leviton AE (1983) Patterns of evolution in Galápagos organisms. Pacific Division, AAAS, San Francisco, 568 pp.

- Miralles A, Macleod A, Rodríguez A, Ibáñez A, Jiménez-Uzcategui G, Quezada G, Vences M, Steinfartz S (2017) Shedding light on the Imps of Darkness: an integrative taxonomic revision of the Galápagos marine iguanas (genus Amblyrhynchus). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 181: 678–710. DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlx007

- MacLeod A, Steinfartz S (2016) The conservation status of the Galápagos marine iguanas, Amblyrhynchus cristatus: a molecular perspective. Amphibia-Reptilia 37: 91–109.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Keynes RD (2001) Charles Darwin’s Beagle diary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 500 pp.