Published January 19, 2023. Updated December 22, 2025. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Cuzco Tegu (Tupinambis cuzcoensis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Teiidae | Tupinambis cuzcoensis

English common name: Cuzco Tegu.

Spanish common name: Lobo pollero.

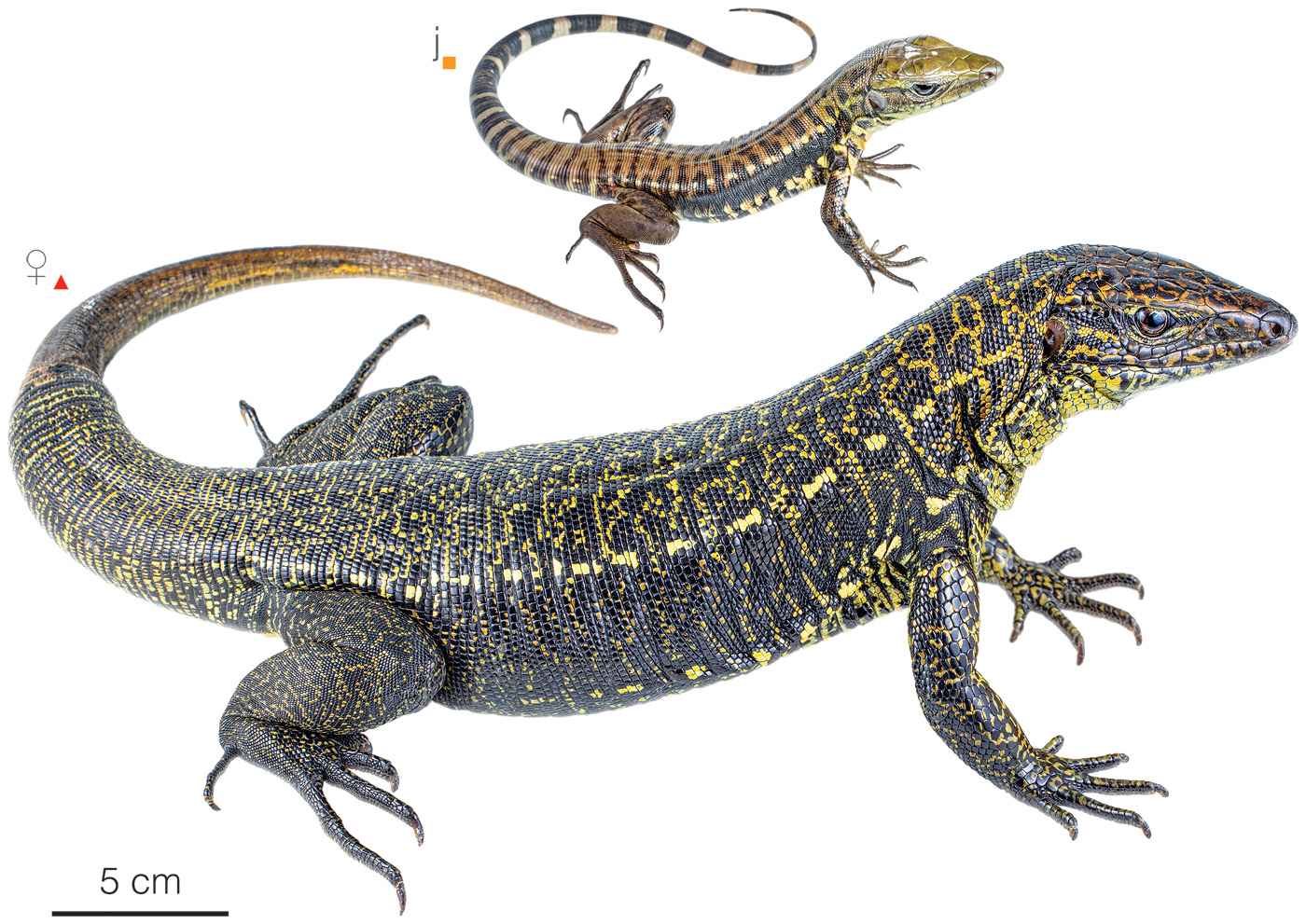

Recognition: ♂♂ 94.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=32.2 cm. ♀♀ 90.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=30.7 cm..1,2 The Cuzco Tegu (Tupinambis cuzcoensis) differs from other Amazonian whiptails by its large size, smooth rectangular ventral scales, and unique coloration.1–3 The dorsal surfaces are black with irregular golden markings and spots.1–3 Juveniles tend to have black flanks and a dorsal coloration consisting of alternating black and golden bars (Fig. 1). Adults of this species can only be confused with Dracaena guianensis, a lizard characterized by having body tubercles and a laterally compressed tail bearing paired dorsal crests.4

Figure 1: Individuals of Tupinambis cuzcoensis from Ecuador: Cuyabeno Reserve, Sucumbíos province (); Río Curaray, Pastaza province (); Zoo de Tarqui, Pastaza province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Tupinambis cuzcoensis is a large diurnal macroteiid most commonly heard crashing through the undergrowth in old growth to moderately disturbed rainforests, which may be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.1,3 The species prefers semi-open habitats, being found mostly on clearings, tree-fall areas, forest edges, plantations, and peri-urban areas.1,5 Cuzco Tegus require extended periods of direct sunlight to become active,5 typically being out between 11:00 am and 3:30 pm.3 At night, Cuzco Tegus seek shelter in burrows or holes under fallen logs or among roots.5 Despite being primarily terrestrial, these lizards are good swimmers and climbers, commonly seen basking on logs up to 3 m above the water’s edge1,6 or on vegetation islands during the flood season.7 The majority of their active time is spent basking on filtered sunlight or frantically foraging, essentially never stopping as they noisily scratch in search for food.5 Their diet is opportunistic and includes insects and their larvae, spiders, mollusks, earthworms, centipedes, frogs, lizards, small mammals, birds, fruits, and leaves.1,3–8 A preferred prey item is eggs of turtles (Podocnemis unifilis3) and crocodilians (Caiman crocodilus and Melanosuchus niger).9 Tegus are infamous for their tendency to attack poultry, especially young chicks, and to rob chicken nests of eggs.7 There are documented instances of predation on members of this species by snakes (Eunectes murinus10 and Pseudoboa coronata6). Clutches consist of 5 eggs deposited in arboreal termite nests up to 3 m above the ground.5,7

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Tupinambis cuzcoensis is a recently described species; therefore, its conservation status has not yet been formally evaluated by the IUCN. Here, it is proposed to be included in the Least Concern category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, presence in protected areas, and presumed large stable populations. Observations in Ecuador indicate a growing abundance of this species as a response to the conversion of dense-canopy rainforests into selectively logged semi-open environments.1 In some areas of the Amazon, the meat and eggs of T. cuzcoensis are consumed and the skin is used as material for handicrafts and various garments.7

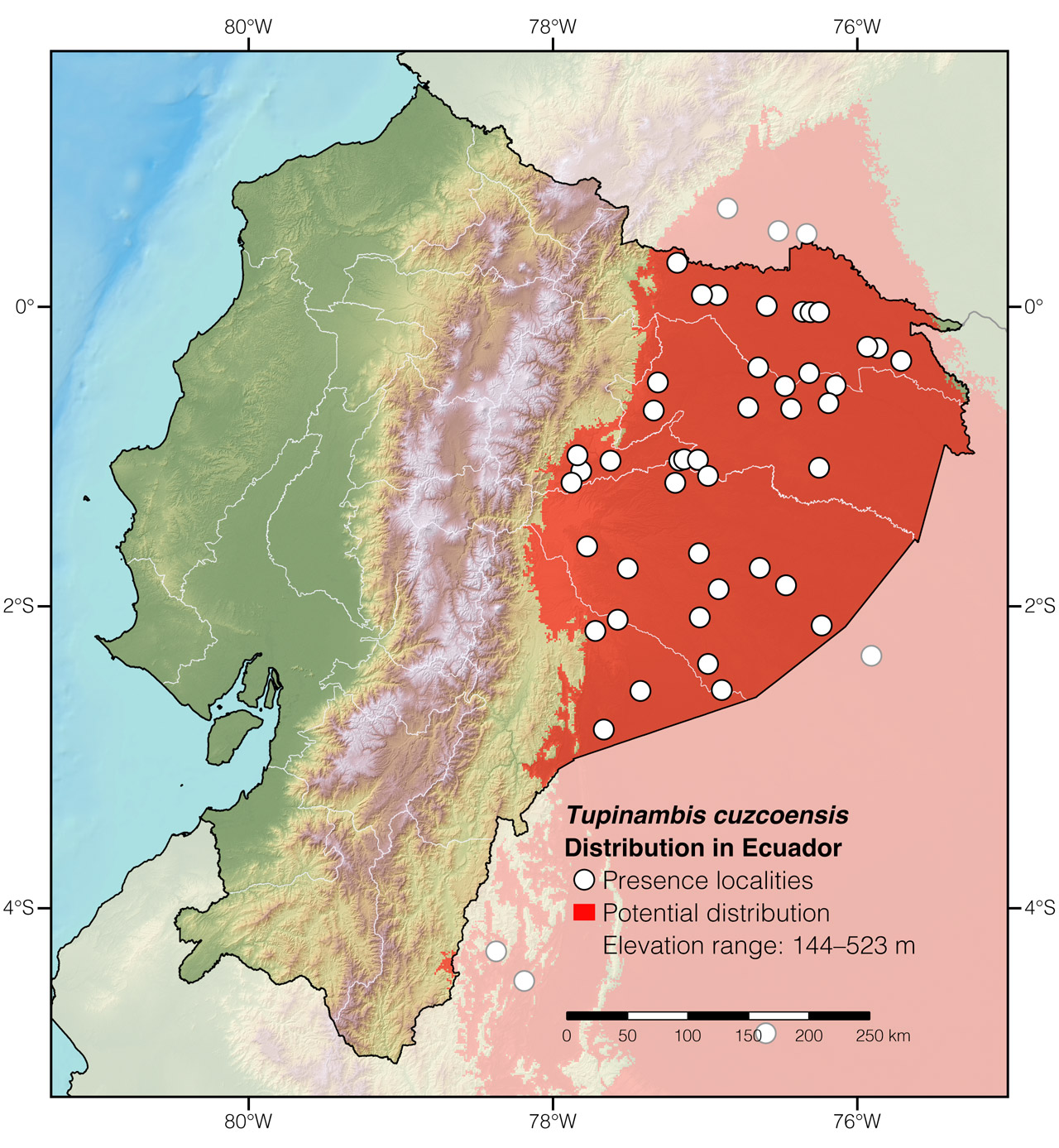

Distribution: Tupinambis cuzcoensis is widely distributed throughout the western Amazon basin of Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Tupinambis cuzcoensis in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Tupinambis refers to the Tupinambá indigenous tribe, one of several Tupi ethnic groups that inhabited Brazil at the time of European arrival.11 The specific epithet cuzcoensis refers to the type locality: Cusco.2

See it in the wild: Cuzco Tegus are comparatively easily sighted within their distribution range in Ecuador, especially in Yasuní Scientific Station and along the Río Cuyabeno. These jittery reptiles are more easily observed sunning on logs at the river’s edge.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2025) Cuzco Tegu (Tupinambis cuzcoensis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/TYNF2965

Literature cited:

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Murphy JC, Jowers MJ, Lehtinen RM, Charles SP, Colli GR, Peres Jr AK, Hendry CR, Pyron RA (2016) Cryptic, sympatric diversity in tegu lizards of the Tupinambis teguixin Group (Squamata, Sauria, Teiidae) and the description of three new species. PLoS ONE 11: e0158542. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0158542

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Vitt LJ, De la Torre S (1996) A research guide to the lizards of Cuyabeno. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, 165 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Castro Herrera F, Ayala SC (1988) Saurios de Colombia. Unpublished, Bogotá, 692 pp.

- Da Silveira R, Ramalho EE, Thorbjarnarson JB, Magnusson WE (2010) Depredation by jaguars on caimans and importance of reptiles in the diet of jaguar. Journal of Herpetology 44: 418–424. DOI: 10.1670/08-340.1

- Thomas O, Allain SJR (2021) A review of prey taken by anacondas (Squamata: Boidae: Eunectes). Reptiles & Amphibians 28: 329–334.

- Uetz P, Freed P, Hošek J (2021) The reptile database. Available from: www.reptile-database.org.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Tupinambis cuzcoensis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Platanillo | Restrepo-Isaza 2021 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Castro Herrera & Ayala (unpublished) |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Yarumo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Villa Ashuara | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pitalala, meseta | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Shiripuno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Suchipakari Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zatzayacu | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Edén, 4 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nenkepare | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Iro | Pazmiño-Otamendi et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuni Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Murphy et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pindoyacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Capahuari | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Curaray medio | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pastaza | Murphy et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pintoyacu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | UNOCAL Base Camp | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Zábalo | Cevallos Bustos 2010 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Cuyabeno River Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Kichwa Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Parque de Nueva Loja | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Playas del Cuyabeno | Murphy et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pozo Shuara | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente del Río Cuyabeno, 7 km E of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Bermejo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Cuyabeno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huambisa Village | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Kayamas | USNM 316907; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Shaim | USNM 316910; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | Dixon & Soini 1986 |

| Perú | Loreto | San Jacinto | KU 222188; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | San Juan | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |