Published September 1, 2023. Updated January 15, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Northern Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Teiidae | Dracaena guianensis

English common names: Northern Caiman-Lizard, Alligator Lizard.

Spanish common name: Lagarto caimán.

Recognition: ♂♂ 126.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=42.0 cm. ♀♀ 113.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=41.2 cm..1–4 Dracaena guianensis, a lizard that resembles a blunt-snouted crocodilian, is the largest saurian in the Ecuadorian Amazon. It can be recognized by its remarkable appearance, body tubercles arranged in 4–6 rather irregular longitudinal rows, and laterally compressed tail bearing paired dorsal crests (Fig. 1).1–3 The only other co-occurring lizard that approaches this size is Tupinambis cuzcoensis, a species distinguishable by its uniformly small dorsal scales, long snout, and entirely different coloration.2

Figure 1: Individuals of Dracaena guianensis: Río Yasuní, Orellana province, Ecuador (); Yarina Lodge, Orellana province, Ecuador; (); unknown locality (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Dracaena guianensis is a locally frequent lizard in the northern Amazon rainforest of Ecuador, specifically in areas of várzea (=whitewater-flooded forests) and igapó (=blackwater-flooded forests). Northern Caiman Lizards are semi-aquatic and semi-arboreal, inhabiting seasonally flooded rainforests, swamps, lagoons, and margins of rivers and streams.1 Active during the daytime when ambient temperatures hover around 29°C,5 these large saurians forage in both aquatic and terrestrial environments.1,2 However, most of the time is spent resting or thermoregulating on lower tree branches.1,5 Occasionally, individuals may be seen crossing roads far from the water’s edge,6 or even swimming into the streets of villages or cities during the flood season.7 They are skilled climbers, thanks to their strong clawed limbs and mildly prehensile tail.4 At night, they roost on branches of trees 2–5 m above the water surface,6 or in burrows in the substrate.4 When startled, individuals usually plunge into the water and dive to the bottom or run into holes in the bank1–7; if grabbed, they can also shed the tail.6 Although they are generally well-tempered and not prone to aggression, Caiman Lizards may resort to biting or attacking when cornered.4 Instances of male-male territorial aggression are quite rare.4 The diet in this species is almost exclusively composed of snails and clams.1–7 They use their large flattened teeth to crush shells and then spit out the fragments.2,7 During the dry season, their diet may include arboreal invertebrates, eggs, and other animal prey.5 Dracaena guianensis is an oviparous species. There is a report of two eggs found in a cavity in a termite nest at the margin of a river.1 In captivity, the clutch size is 4–7 eggs, and the incubation period lasts around 161 days (approximately 5.4 months).4 Hatchlings measure ~15 cm in snout-vent-length.4

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..8 Dracaena guianensis is listed in this category given its wide distribution, presence in major protected areas, and lack of widespread threats.8,9 Historical records suggest a significant population decline during the 1950s and 1960s, with unregulated large-scale hide hunting and direct consumption being the primary culprits.5 In present times, the most pressing threat to populations of D. guianensis in Ecuador is the expansion of the agricultural frontier in the vicinity of Coca and Lago Agrio cities.6

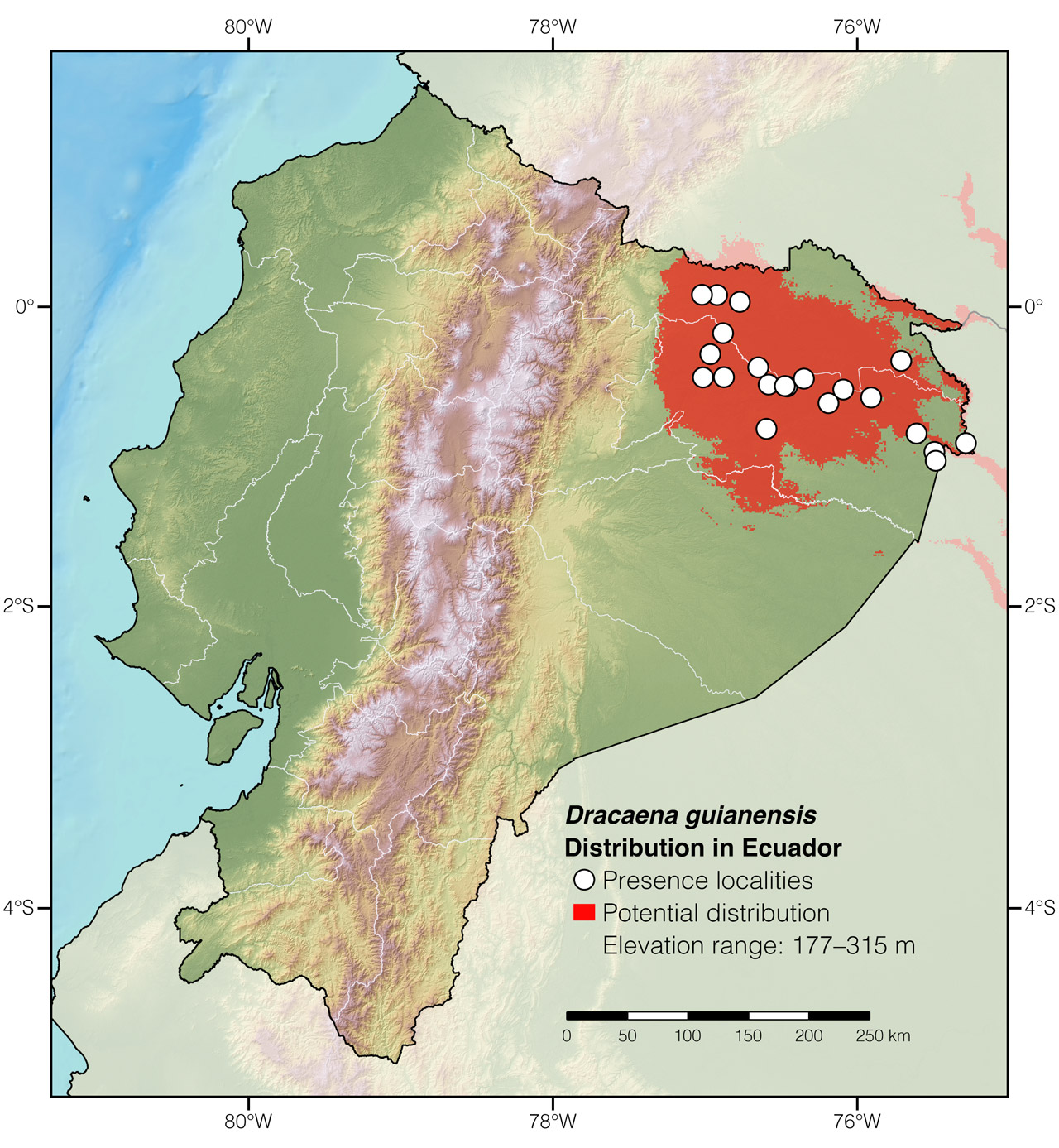

Distribution: Dracaena guianensis is widely distributed throughout the Amazon basin in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, and Perú (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Dracaena guianensis in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Dracaena is derived from the Greek word drakaina, a “she-dragon.”10 The specific epithet guianensis refers to the type locality: French Guiana.1

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Northern Caiman Lizards are spotted routinely along streams and rivers that flow into the Napo River. Most recent observations come from Napo Wildlife Center and Sacha Lodge, where the animals are usually swimming during the day or perched on riparian vegetation.

Special thanks to Cordula Kersten for symbolically adopting the Northern Caiman Lizard and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Northern Caiman Lizard (Dracaena guianensis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/GYLI8954

Literature cited:

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Rehák I (1999) Captive breeding of the caiman lizard, Dracaena guianensis. Herpetofauna 29: 57–60.

- Mesquita DO, Colli GR, Costa GC, França FGR, Garda AA, Péres Jr AK (2006) At the water’s edge: ecology of semiaquatic teiids in Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Herpetology 40: 221–229.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Calderón M, Perez P, Avila-Pires TCS (2019) Dracaena guianensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T44579645A44579652.en

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Amaral S (2016) Diversity, distribution, and conservation of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) in the Brazilian Amazonia. Neotropical Biodiversity 2: 195–421. DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2016.1236769

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dracaena guianensis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Añangu river | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Bloque 43, Campo ITT | Photo by María José Quiroz |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Chiruisla | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Edén Amazon Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | MHNG 2284.057; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Joya de los Sachas, 8 km W of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Maxus road, km 12 | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Rocafuerte, 6 km SW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní, near Lake Jatuncocha | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pastaza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Cocaya | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Zábalo | Cevallos Bustos 2010 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Jivino Verde | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha Biological Reserve | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Parque Ecologico Nueva Loja | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Isla | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Territorio Cofán Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | TCWC 38121; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Aucayo | TCWC 38170; VertNeet |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Marañón | Project Noah |