Published July 4, 2021. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Banded Centipede-Snake (Tantilla supracincta)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Tantilla supracincta

English common names: Banded Centipede-Snake, Coral Crowned Snake.

Spanish common names: Culebra ciempiés bandeada (Ecuador), culebra ciempiés anillada (Colombia), cabeza plana anillada (Costa Rica).

Recognition: ♀♀ 59 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=59.9 cm..1Tantilla supracincta can be recognized from other snakes in its area of distribution by having the following combination of features: smooth dorsal scales arranged in 15 rows at mid-body, a round head similar in width to the neck, small eyes, no loreal scale, and a coral snake coloration consisting of 11–16 black-bordered pale crossbars (some of which are interrupted medially) on a bright red background (Fig. 1).2,3 The black head cap is fused with the first black crossbar and has a cream blotch on the snout and another below and posterior to the orbit.2,4 The belly is bright red but without markings, except the flanks, which are invaded by the dorsal coloration.2,5 The Banded Centipede-Snake can be distinguished from the true coral snakes (genus Micrurus) that inhabit Ecuador by lacking rings that encircle the entire body. This characteristic also serves to differentiate it from the false coralsnakes Lampropeltis micropholis and Erythrolamprus mimus.

Figure 1: Individuals ofTantilla supracincta from Canandé Reserve, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history:Tantilla supracincta is an extremely rare6 semi-fossorial snake that inhabits low elevation seasonally dry forests and evergreen forests.7 The species also occurs in gallery forests6 and pastures.8 Banded Centipede-Snakes have been seen actively moving on leaf-litter or soil during the daytime, around sunset, or at night,6,9,10 or found hidden under logs and debris.5 They are active hunters specialized on centipedes; no other prey items have been recorded.5,11 Individuals are calm, jittery, and rely on their coralsnake coloration as a primary defense mechanism. When threatened, they try to flee by digging into the soil.6 There are records of snakes (Clelia clelia,5 Bothrops asper,12 Erythrolamprus bizona,5 and Micrurus transandinus)13 preying upon individuals of this species. These snakes are opisthoglyphous (having enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla) and mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans. In Costa Rica, the clutch size of this species is 1–3 eggs.14,15

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..16,17Tantilla supracincta is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, especially in areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, like the Colombian Pacific coast, and is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for a more threatened category.16 The most important threat for the long-term survival of some populations is the loss of habitat due to large-scale deforestation. Based on maps of Ecuador’s vegetation cover published in 2012,18 approximately 58% of the native forest habitat of T. supracincta has already been destroyed in this country. The fear of snakes is also a source of mortality to individuals of this species. People in rural regions tend to kill any snake, even those not dangerous to them. There is published information19 that suggests that this snake species suffer from traffic mortality.

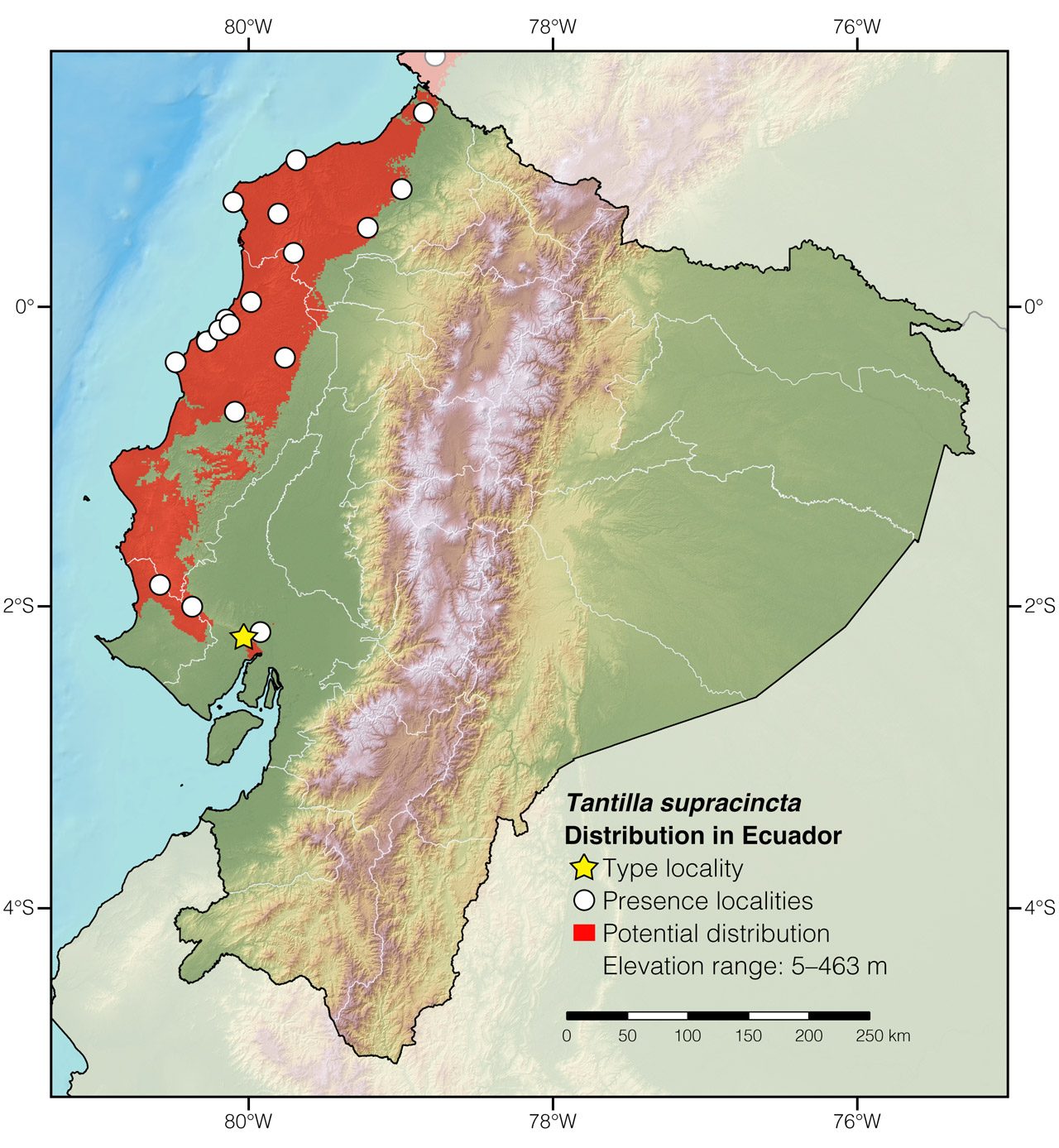

Distribution:Tantilla supracincta is native to the Mesoamerican and Chocoan lowlands, from southern Nicaragua to western of Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution ofTantilla supracincta in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The genus nameTantilla is derived from the Latin word tantillus (=little)20 and probably refers to the small body size in snakes of this genus. The specific epithet supracincta comes from the Latin words supra (=above) and cinctum (=belt),20 referring to the dorsal crossbars.11

See it in the wild: Seen at a rate of about once every few months, especially along the forested coastal foothills of Manabí province. The best way to find these snakes is to slowly cruise through dirt roads along areas of well-preserved forest at dusk, especially during the rainy season.

Acknowledgments: This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2021) Banded Centipede-Snake (Tantilla supracincta). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/GYPH7930

Literature cited:

- Wilson LD, Mena CE (1980) Systematics of the melanocephala group of the colubrid snake genusTantilla. Memoirs of the San Diego Society of Natural History 11: 5–58.

- Wilson LD (1982) A review of the colubrid snakes of the genusTantilla of Central America. Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology 52: 1–77.

- Solórzano A (2004) Serpientes de Costa Rica. Distribución, taxonomía e historia natural. Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, 792 pp.

- Wilson LD (1987) A Résumé of the Colubrid snakes of the genusTantilla of South America. Milwaukee Public Museum Contributions in Biology and Geology 68: 1–35.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Gómez-Rincón MT, Vásquez-Restrepo JD (2020)Tantilla supracincta (Banded Centipede Snake). Habitat. Herpetological Review 51: 157.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF (2005) Reptilia, Serpentes, Colubridae,Tantilla supracincta: filling gap, first provincial record, geographic distribution map, and natural history. Check List: 23–26. DOI: 10.15560/1.1.23

- Regdy Vera, pers. comm.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Leenders T (2019) Reptiles of Costa Rica: a field guide. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 625 pp.

- Peters WCH (1863) Über einige neue oder weniger bekannte Schlangenarten des zoologischen Museums zu Berlin. Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin 1863: 272–289.

- Gabrysova B, Aznar González de Rueda J, Barrio-Amorós CL (2020) Bothrops asper (Terciopelo). Diet/ophiophagy. Herpetological Review 51: 859–860.

- Photo by Amado Chávez.

- Goldberg SR (2015)Tantilla supracincta (Banded Centipede Snake). Reproduction. Herpetological Review 46: 454–455.

- Ryan MJ, Latella IM, Willink B, García-Rodríguez A, Gilman CA (2015) Notes on the breeding habits and new distribution records of seven species of snakes from southwest Costa Rica. Herpetology Notes 8: 669–671.

- Acosta Chaves V, Batista A, García Rodríguez A, Vargas Álvarez J, Valencia J, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2017)Tantilla supracincta. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T203328A2764032.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Hurtado-Gómez JP, Grisales-Martínez FA, Rendón-Valencia BE (2015) Starting to fill the gap: first record ofTantilla supracincta (Peters, 1863) (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Colombia. Check List 11: 1–4. DOI: 10.15560/11.4.1713

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map ofTantilla supracincta in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Guayacanes | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Station | Ortega-Andrade et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Cabeceras de Bilsa | Almendariz & Carr 2007 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Caimito | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Wilson et al. 1977 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Terminal Marítimo OCP | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Zapallo Grande | MHNG 2452.090 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Chongón hills, near Guayaquil* | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Mapasingue | MHNG 2248.094 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Bosque Seco Lalo Loor | Hamilton et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cabo Pasado | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cerro Pata de Pájaro | Hamilton et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Chone | Photo by Redgy Vera |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama, 3 km S of | DHMECN 5664 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Crespa | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Biológica Tito Santos | Hamilton et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Jama Coaque | Lynch et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Reserva Ecológica Comunal Loma Alta | Yanez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |