Published May 27, 2024. Open access.

Elegant Racer (Pseudalsophis elegans)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Pseudalsophis elegans

English common name: Elegant Racer.

Spanish common names: Culebra elegante de desierto, culebra elegante de cola larga.

Recognition: ♂♂ 41.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=30.0 cm. ♀♀ 99.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=76.4 cm..1,2 Pseudalsophis elegans can be identified from other snakes inhabiting the Tumbesian xeric region of southern Ecuador by having a pale grayish tan dorsum with a dark brown mid-dorsal longitudinal stripe with undulating margins anteriorly, but otherwise straight-edged and unbroken (Fig. 1).1,3,4 The dorsal scales are smooth and arranged in 19 rows at mid-body.1,3,4 This species differs from snakes of the genus Coniophanes by having apical pits on the dorsal scales and by lacking contrasting stripes on the dorsal aspect of the head.5 From Incaspis simonsii, it differs by having a broad and sinuous, instead of thin and straight, mid-dorsal stripe.6

Figure 1: Adult female of Pseudalsophis elegans from La Ceiba Reserve, Loja province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Pseudalsophis elegans is a diurnal and terrestrial snake that inhabits deserts and seasonally dry forests and shrublands near the coast.1,7 During the daytime, these snakes are typically seen swiftly moving at ground level,7 but some have been seen climbing tree trunks or rock walls up to 4 m above the ground.8,9 At night or during cold weather, individuals have been found under surface debris, in crevices, or inside houses.7 Snakes of the genus Pseudalsophis in general are mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.10 The diet in P. elegans includes lizards, with Dicrodon guttulatum2 and Macropholidus ruthveni11 having been recorded as prey items. The clutch size in this species consists of six eggs.2

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..12 Pseudalsophis elegans is listed in this category primarily because of the species’ wide distribution and presence in disturbed areas suggests no major population declines, although the proximity to these populated areas increases death events.13 The main threat to the long-term survival of Ecuadorian populations of P. elegans is the continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat, mostly due to encroaching human activities such as agriculture, cattle grazing, and wild fires.

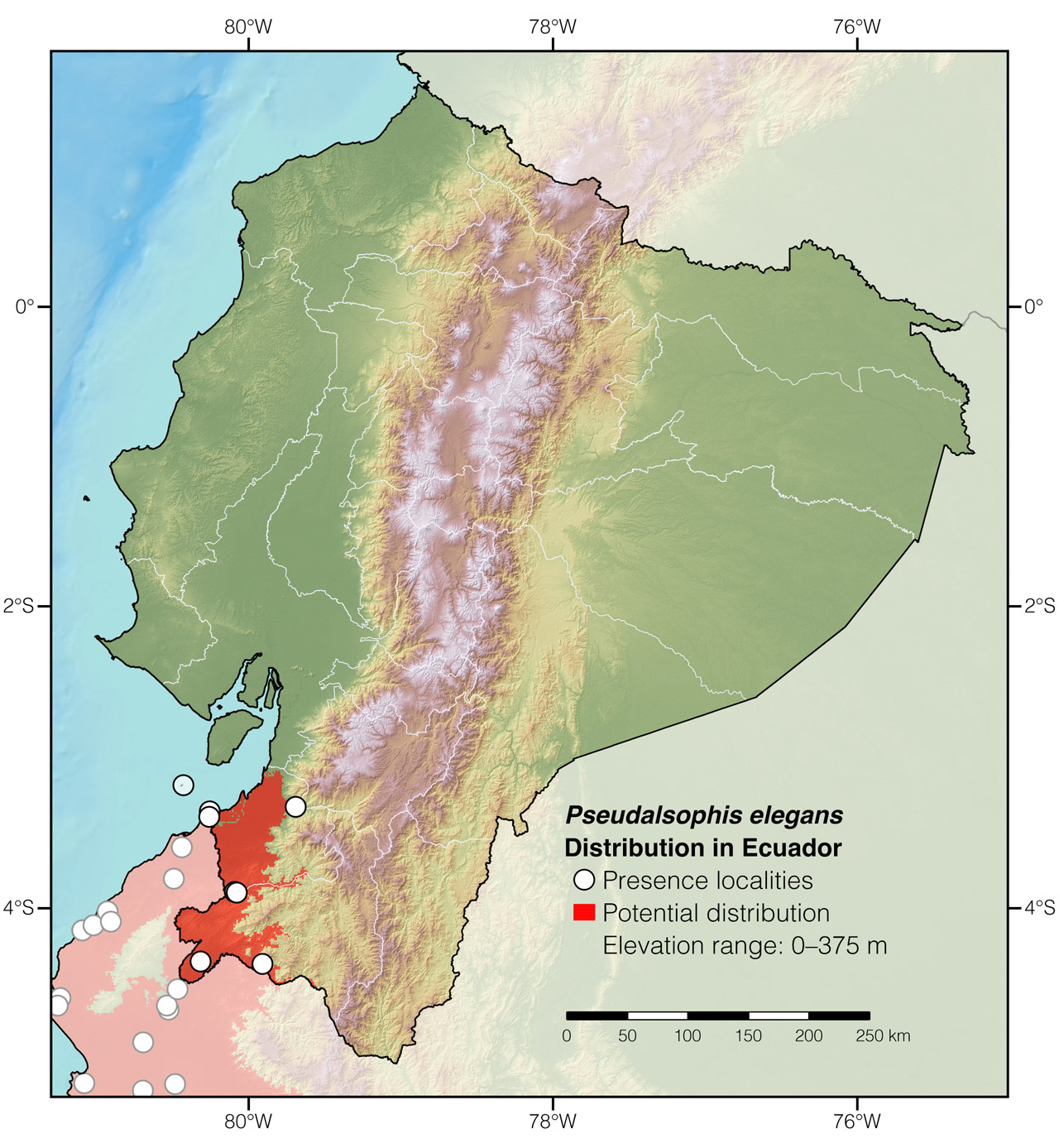

Distribution: Pseudalsophis elegans is widely distributed over a ~2,300 km stretch of coastline along the Pacific, from southwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2), through the entire coast of Peru, to northern Chile.

Figure 2: Distribution of Pseudalsophis elegans in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Pseudalsophis comes from the Greek words pseudo (=false) and Alsophis (a genus of Caribbean snakes), referring to the similarity between snakes of the two genera.10 The specific epithet elegans is a Latin word meaning “elegant.”14 It refers to the ornate dorsal color pattern.

See it in the wild: The Elegant Racer is not a common species, but it can be seen at a rate of about once every few weeks at La Ceiba Reserve and at Bosque Protector Puyango. These snakes are most easily observed by walking along semi-open areas during the first hours after sunrise or right before sunset.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Elegant Racer (Pseudalsophis elegans). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/NYNA8968

Literature cited:

- Myers CW, Hoogmoed MS (1974) Zoogeographic and taxonomic status of the South American snake Tachymenis surinamensis (Colubridae). Zoologische Mededelingen 48: 187–194.

- Jujan Leiva L, Malqui Uribe J, Venegas Ibañez PJ (2020) Pseudalsophis elegans rufidorsatus (Guayaquil Racer): diet and reproduction. Herpetological Review 51: 877.

- Schmidt KP, Walker WF (1943) Snakes of the Peruvian coastal region. Zoological Series of Field Museum of Natural History 24: 297–327.

- Thomas RA, Ineich I (1999) The identity of the syntypes of Dryophylax freminvillei with comments on their locality data. Journal of Herpetology 33: 152–155.

- Peters JA, Orejas-Miranda B (1970) Catalogue of Neotropical Squamata: part I, snakes. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 347 pp.

- Zaher H, Arredondo JC, Valencia JH, Arbeláez E, Rodrigues MT, Altamiro-Benavides M (2014) A new Andean species of Philodryas (Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) from Ecuador. Zootaxa 3785: 469–480. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3785.3.8

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photo by Lynn Válery Castro.

- Acosta Vásconez AN (2014) Diversidad y composición de la comunidad de reptiles del Bosque Protector Puyango. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 157 pp.

- Zaher H, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Rodrigues MT, Graboski R, Machado FA, Altamirano-Benavides M, Bonatto SL, Grazziotin FG (2018) Origin and hidden diversity within the poorly known Galápagos snake radiation (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Systematics and Biodiversity 16: 614–642. DOI: 10.1080/14772000.2018.1478910

- Guzmán R (2010) Secretos de los reptiles. Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, 137 pp.

- Richman N, Böhm M, Sallabery N (2017) Pseudalsophis elegans. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T176332A69941784.en

- Hurtado Ordinola LJ (2021) Especies de fauna silvestre muertas por atropellamiento en la carretera Sullana–Lancones, Piura, Perú. BSc thesis, Piura, Universidad Nacional de Piura, 112 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Pseudalsophis elegans in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Galayacu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Isla Costa Rica | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Isla San Gregorio | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Las Lajas | Garzón-Santomaro, et al. 2019; BioWeb |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Santa Clara | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Bosque Petrificado Puyango | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Jorupe Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | La Ceiba Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | Piura | Bayovar | Thomas & Ineich 1999 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones, km 2 | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones, km 33 | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones, km 40 | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones, km 58 | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones, km 64 | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Cerro Illescas | Thomas & Ineich 1999 |

| Perú | Piura | Negritos | Schmidt & Walker 1943 |

| Perú | Piura | Paita | Thomas & Ineich 1999 |

| Perú | Piura | Piura | FMNH 38682; VertNet |

| Perú | Piura | Piura, 15 km E of | Thomas & Ineich 1999 |

| Perú | Piura | Playa Vichayito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Puente de Máncora | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | Piura | Talara | Photo by Pablo Venegas |

| Perú | Piura | Verdun Alto | FMNH 5730; VertNet |

| Perú | Tumbes | Cerro Salvajal | Jujan Leiva et al. 2020 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Negritos, 50 mi N of | Myers & Hoogmoed 1974 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Quebrada San Grande | FMNH 8386; VertNet |

| Perú | Tumbes | Quebrada Seca | Myers & Hoogmoed 1974 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Universidad Nacional de Tumbes | iNaturalist; photo examined |