Published May 8, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Simon’s Andean Racer (Incaspis simonsii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Incaspis simonsii

English common name: Simon’s Andean Racer.

Spanish common name: Culebra altoandina de Simons.

Recognition: ♂♂ 78 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 89.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=61.1 cm..1,2 Incaspis simonsii differs from other snakes in its area of distribution by having an acuminate snout, round pupils, smooth dorsal scales, and a striped dorsum (Fig. 1).1,3 There is a thin black mid-dorsal stripe bounded by two broad olive green stripes, which are themselves bordered below by tan stripes.1,4 The lower flanks tend to be pale olive gray. This species differs from I. amaru by having thin (1 dorsal scale row wide) brown longitudinal lines rather than broad black ones.1,4 From Erythrolamprus fraseri and Dendrophidion brunneum, it differs by having longitudinal black lines along the entire length of the body, not only on the posterior half of it.

Figure 1: Individuals of Incaspis simonsii from Ecuador: La Paz, Azuay province (); Sendero Laguna Chuquiragua, Loja province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Incaspis simonsii is a terrestrial, semi-arboreal, and diurnal snake that inhabits high elevation grasslands and shrublands, occurring in lower densities in altered environments such as open fields.1,5–7 During sunny days, Simon’s Andean Racers have been observed swiftly moving on grass, through low bushes, or basking on rocks.1,5,6 At night or during cold weather, they remain hidden in crevices or under logs.5,6 Incaspis simonsii has an opisthoglyphous dentition, meaning it has enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla and is venomous to small prey, but harmless (or only mildly venomous) to humans.8,9 The diet in this species consists of lizards (Stenocercus simonsii10) and toads.5 The High-Andean Racer, when threatened, usually tries to flee quickly, but it can also be aggressively defensive when cornered.6

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..7 Incaspis simonsii is listed in this category because the species has a wide distribution spanning many protected areas. Although it is a rarely seen snake, this could probably be owed to the difficulty in detecting it in the field rather than to actual low population densities. The main threats to Ecuadorian populations of I. simonsii are habitat destruction due to rural-urban expansion and the replacement of native vegetation with pine and eucalyptus plantations.

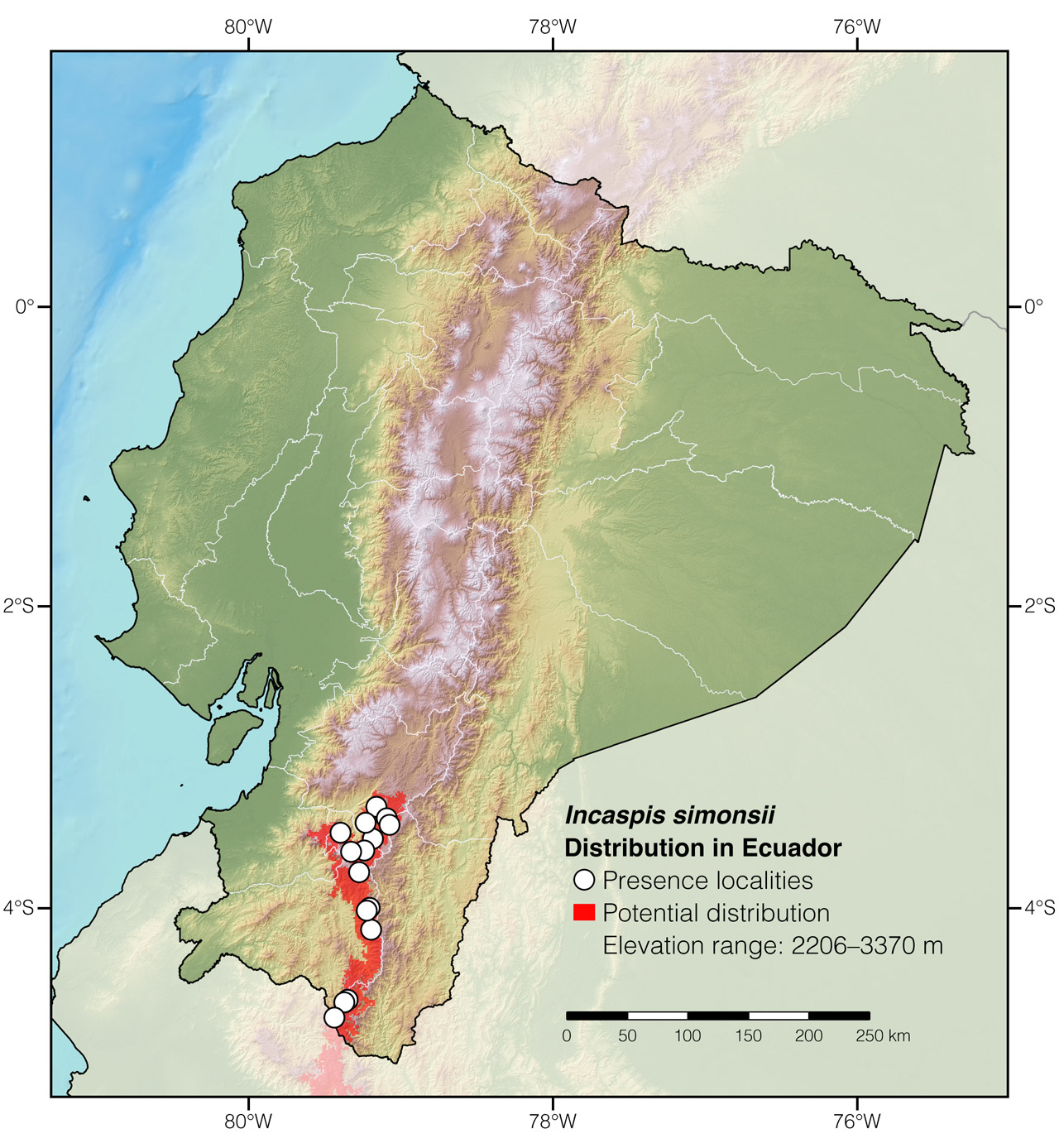

Distribution: Incaspis simonsii is widely distributed throughout the high Andes of Perú and southern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Incaspis simonsii in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The genus name Incaspis is a combination of the Quechua word Inca (=royalty) and the Greek word aspis (=venomous snake), in reference to the Inca Empire.8 The specific epithet simonsii honors Perry O. Simons (1869–1901), an U.S. explorer who collected in the Neotropics, including Perú (1899–1900) and Bolivia (1901). He was murdered by his guide while crossing the Andes.11

See it in the wild: Simon’s Andean Racers can be seen at a rate of about once every few years throughout their area of distribution in Ecuador. The greatest number of recent observations are of snakes crossing dirt roads during the early morning along the upper watershed of the Río Jubones in southern Ecuador.

Authors: Tatiana Molina-Moreno,aAffiliation: Departamento de Biología, Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. Andrés F. Aponte-Gutiérrez,bAffiliation: Grupo de Investigación en Ciencias de la Orinoquía, Universidad Nacional de Colombia sede Orinoquía, Arauca, Colombia.,cAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagaeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirafAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,gAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Molina-Moreno T, Aponte-Gutierrez AF, Arteaga A (2024) Simon’s Andean Racer (Incaspis simonsii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/AHVI3036

Literature cited:

- Schmidt KP, Walker WF (1943) Snakes of the Peruvian coastal region. Zoological Series of Field Museum of Natural History 24: 297–327.

- Wallach V, Kenneth LW, Boundy J (2014) Snakes of the world: a catalogue of living and extinct species. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1237 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1900) Descriptions of new batrachians and Reptiles collected by Mr. P. O. Simons in Peru. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 6: 181–186.

- Zaher H, Arredondo JC, Valencia JH, Arbeláez E, Rodrigues MT, Altamiro-Benavides M (2014) A new Andean species of Philodryas (Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) from Ecuador. Zootaxa 3785: 469–480. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3785.3.8

- Péfaur JE, Núñez A, López E, Dávila J (1978). Distribución y clasificación de los reptiles del Departamento de Arequipa. Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines 7: 129–139.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Sallabery N, Cisneros-Heredia D, Yánez-Muñoz M, Lundberg M (2017) Incaspis simonsii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T15182216A15182218.en

- Arredondo JC, Grazziotin FG, Scrocchi GJ, Rodrigues MT, Bonatto SL, Zaher H (2020) Molecular phylogeny of the tribe Philodryadini Cope, 1886 (Dipsadidae: Xenodontinae): rediscovering the diversity of the South American racers. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 60: e20206054. DOI: 10.11606/1807-0205/2020.60.54

- Urra FA, Pulgar R, Gutiérrez R, Hodar C, Cambiazo V, Labra A (2015) Identification and molecular characterization of five putative toxins from the venom gland of the snake Philodryas chamissonis (Serpentes: Dipsadidae). Toxicon 108: 19–31. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2015.09.032

- Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm.

- Uetz P, Freed P, Hošek J (2021) The reptile database. Available from: www.reptile-database.org.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Incaspis simonsii in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Cuenca, 95 km S of | MHNG 2401.027; collection database |

| Ecuador | Azuay | La Paz | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Morasloma-Cochapata | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Vía Poetate–Susudel | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Amaluza, 9 km E of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Carretera Saraguro–Urdaneta | MUTPL 118; GBIF |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 10 km S of | MHNG 2532.03; collection database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 35 km N of | Zaher et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, UTPL | MHNG 2401.028; collection database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja* | Zaher et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Manú | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Selva Alegre | Pazmiño-Otamendi 2024 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Sendero Laguna Chuquiragüa | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Parque Nacional Yacuri | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tutupali | Pazmiño-Otamendi 2024 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Cajamarca* | Boulenger 1900 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | El Pargo | MCZ 179419; GBIF |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Río Zaña | FMNH 232579; VertNet |