Published February 25, 2021. Updated January 29, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Valley Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus simonsii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Tropiduridae | Stenocercus simonsii

English common names: Valley Whorltail-Iguana, Simons’ Whorltail-Iguana.

Spanish common names: Guagsa del valle, Guagsa de Simons.

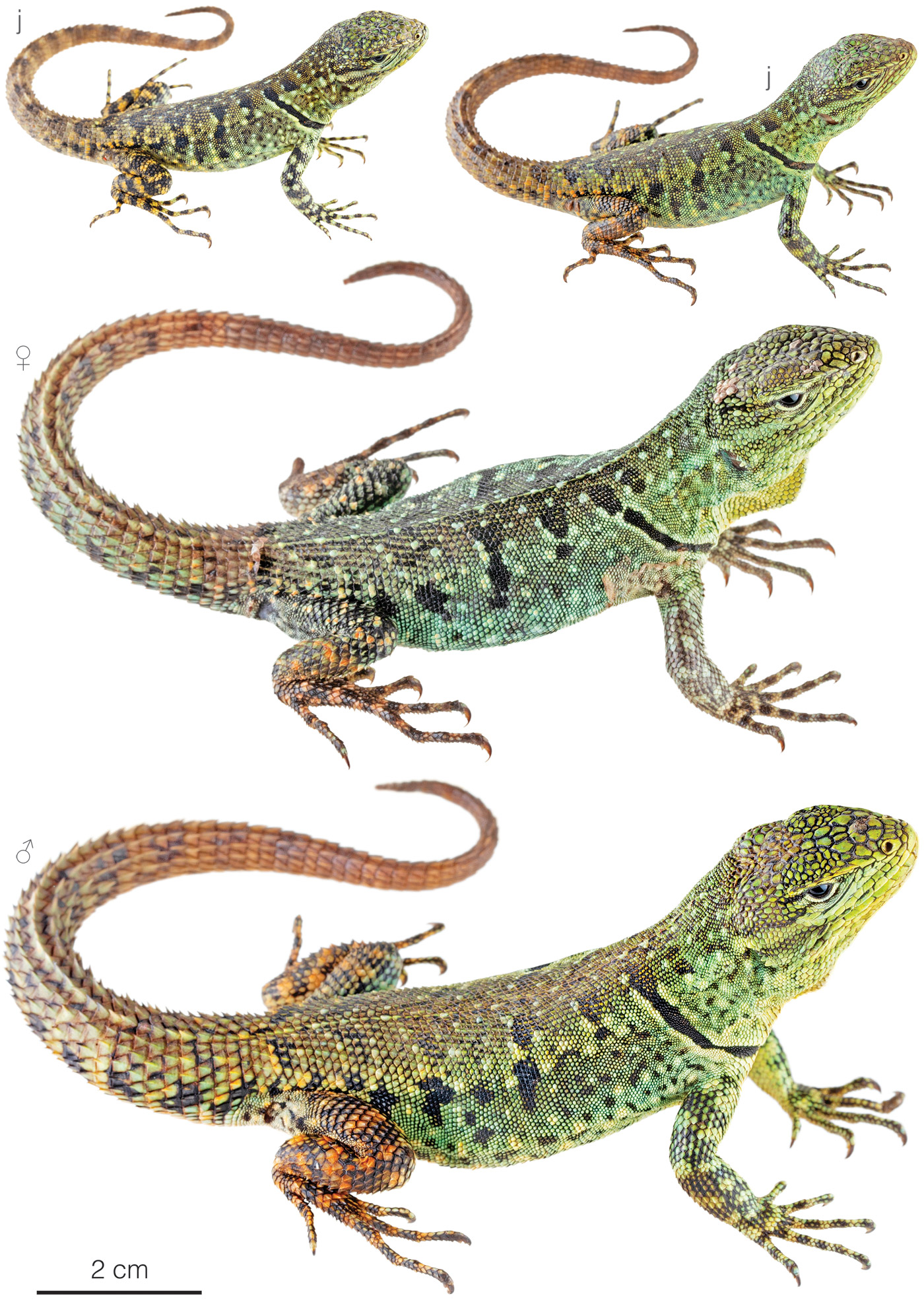

Recognition: ♂♂ 20 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.8 cm. ♀♀ 18.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.9 cm..1 The Valley Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus simonsii) has a unique morphology that differentiates it from other lizards in the valley of the Río Jubones. It has granular dorsal scales and a markedly spiny tail.2,3 Males of S. simonsii differ from females by being slightly more robust and having a broader head, but both sexes are otherwise similar in color and size.1 Individuals of S. simonsii from the southern, drier part of the distribution differ in coloration (they have a pale-gray dorsum; Fig. 1) and pattern of scale arrangement from those in the northern more humid part of the range (Fig. 2),2 which have a bright green dorsum.

Figure 1: Individuals of Stenocercus simonsii from La Merced, Azuay province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Stenocercus simonsii is a diurnal lizard that inhabits the dry to humid highland shrubland ecosystem. It occurs in areas containing a matrix of native vegetation, rural gardens, human settlements, and pastures.1,2 Valley Whorltail-Iguanas are most active on sunny days. They can be seen basking or moving at ground level or on stone piles, rock walls, rooftops, cliffs, and bromeliads up to 3.4 m above the ground.2–5 On cloudy days, they remain hidden under rocks or in crevices. When threatened, individuals take refuge in vegetation, under rocks, or in cracks in stone walls; they expand the body and press the spiny tail against the stones in order to make their capture difficult.4 If captured, they may shed the tail and bite as a method of defense and escape.4 There are records of individuals of this species being preyed upon by snakes (Bothrocophias lojanus and Incaspis amaru).6,7 As in many species of lizards in the family Tropiduridae, S. simonsii has mite pockets that help concentrate these parasites to avoid infestations.8

Figure 1: Individuals of Stenocercus simonsii from El Chorro de Girón, Azuay province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Conservation: Endangered Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the near future..9 Stenocercus simonsii is listed in this category because the species’ extent of occurrence is less than 1,000 km2 and its habitat is declining in extent and quality due to increased human activities such as infrastructure expansion, agriculture, and livestock grazing.9 Approximately 70% of the native shrubland habitat of S. simonsii has already been destroyed.10 Furthermore, El Chorro Protected Forest is the only protected area where the species has been reported.

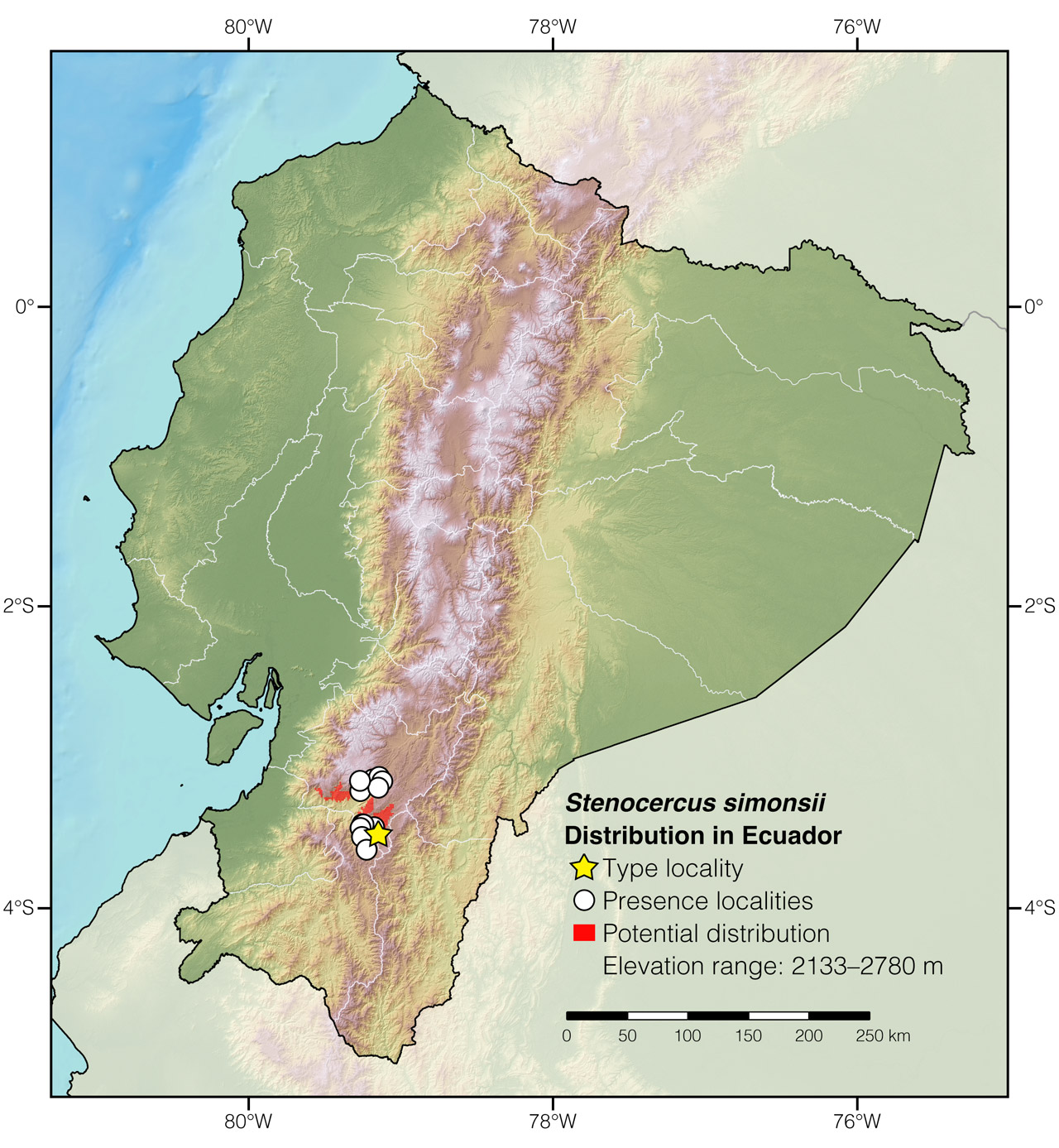

Distribution: Stenocercus simonsii is endemic to an area of approximately 930 km2 in the xeric inter-Andean valley of the Río Jubones in southern Ecuador (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Distribution of Stenocercus simonsii in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Oña, Azuay province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Stenocercus, which comes from the Greek words stenos (=narrow) and kerkos (=tail), refers to the laterally-compressed tail in some members of this genus, which contrasts with the dorsally flattened tail of other Tropiduridae.11 The specific name simonsii honors Perry Oveitt Simons (1869–1901), an American scientific collector who collected the holotype of the species.12

See it in the wild: Valley Whorltail-Iguanas can be seen with almost complete certainty during strongly sunny days in the surroundings of El Chorro Protected Forest, Azuay province. The lizards may be spotted as they bask on stone walls or rock piles along dirt roads and trails, especially during the mid-morning.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Ernesto Arbeláez and Jorge Luis Romero for for providing locality data and natural history information for Stenocercus simonsii.

Special thanks to Roy and Laurie Averill-Murray for symbolically adopting the Valley Whorltail-Iguana and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A, Arteaga A (2024) Valley Whorltail-Iguana (Stenocercus simonsii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/CEBC8095

Literature cited:

- Cadle JE (1991) Systematics of Lizards of the genus Stenocercus (Iguania: Tropiduridae) from Northern Perú: new Species and comments on relationships and distribution patterns. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia 143: 1–96.

- Torres-Carvajal O (2000) Ecuadorian lizards of the genus Stenocercus (Squamata: Tropiduridae). Scientific Papers Natural History Museum, The University of Kansas 15: 1–38. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.16286

- Torres-Carvajal O (2007) A taxonomic revision of South American Stenocercus (Squamata: iguania) lizards. Herpetological Monographs 21: 76–178. DOI: 10.1655/06-001.1

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Fritts TH (1974) A multivariate and evolutionary analysis of the Andean iguanid lizards of the genus Stenocercus. Memoirs of the San Diego Society of Natural History 7: 1–89.

- Field notes of Jorge Luis Romero.

- Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm.

- Arnold EN (1986) Mite pockets of lizards, a possible means of reducing damage by ectoparasites. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 29: 1–21.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Valencia J, Brito J, Almendáriz A, Muñoz G (2019) Stenocercus simonsii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T50950723A50950728.en

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron G (1837) Erpétologie générale ou Histoire Naturelle complète des Reptiles. Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 571 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

- Boulenger GA (1899) Descriptions of new reptiles and batrachians collected by Mr. P.O. Simons in the Andes of Ecuador. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 7: 454–457.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Stenocercus simonsii in Ecuador (Fig. 3). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Chorros de Girón, 1 km W of | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Girón | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Girón, 3.3 km NE of | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Girón, 3.7 km NE of | Torres-Carvajal 2005 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | La Asunción | José Manuel, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | La Merced | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Oña* | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Quebrada Panteón | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Trail El Salado–Girón | Venegas et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Turupamba, 4 km SE of | Photo by Ernesto Arbeláez |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Zapote | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Gueledel | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Saraguro | Torres-Carvajal 2007 |