Published May 8, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Hot Spring Racer (Incaspis amaru)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Incaspis amaru

English common name: Hot Spring Racer.

Spanish common name: Culebra de agua termal, serpiente corredora de Amaru.

Recognition: ♂♂ 73.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=50.4 cm. ♀♀ 91.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=67.1 cm..1,2 Incaspis amaru is the only snake known to occur along the valley of the Río Yanuncay.1,2 This species differs from other highland snakes in southern Ecuador by virtue of its unique dorsal coloration. There are three broad (2–3 dorsal scale rows wide) black stripes running along the dorsum, separated from each other by pale goldenrod yellow stripes, with golden lower flanks (Fig. 1).1,2 The only other snake that looks similar and also occurs in Azuay province is I. simonsii, which differs from I. amaru by having thin (1 dorsal scale row wide) brown longitudinal lines.1 This species differs from Erythrolamprus fraseri and Dendrophidion brunneum by having longitudinal black lines along the entire length of the body, not only on the posterior half of it.

Figure 1: Individuals of Incaspis amaru from Termas Pumamaqui, Azuay province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Incaspis amaru is a terrestrial and diurnal snake that inhabits high elevation grassland areas as well as thickets, shrubs, and aquatic vegetation along bodies of water.1,2 The species occurs in higher densities along thermal lagoons near streams and rivers.1,2 During sunny days, Hot Spring Racers have been observed swiftly moving on grass, across water, or basking on rocks.1–3 Their activity occurs within a few meters of thermal springs and only during the hottest hours of the day, usually between 10:30 am and 3:00 pm.1,2 At night or during cold weather, they remain hidden under rocks or in tunnels.1,2 There is no evidence of venom glands in this species, so it is considered harmless to humans. These snakes are extremely jittery, fleeing upon the slightest disturbance. Their diet consists of lizards (Stenocercus festae) and frogs and tadpoles of the genus Gastrotheca. Clutches consist of 9–13 eggs laid under rocks and logs or in underground tunnels at a depth of 150 cm.1,2

Conservation: Critically Endangered Considered to be facing imminent risk of extinction.. Incaspis amaru is proposed to be listed in this category, instead of Data Deficient,4 on the basis of the species’ extremely limited extent of occurrence (approximately 12 km2). Incaspis amaru has only been recorded at four localities along the heavily human-modified margins of the Río Yanuncay, an agricultural area with few remnants of native shrubland vegetation. The remaining habitat is severely fragmented and declining in extent and quality due to cattle grazing and firewood extraction.4 Although the species occurs near Cajas National Park, it has not been recorded within the limits of the protected area.

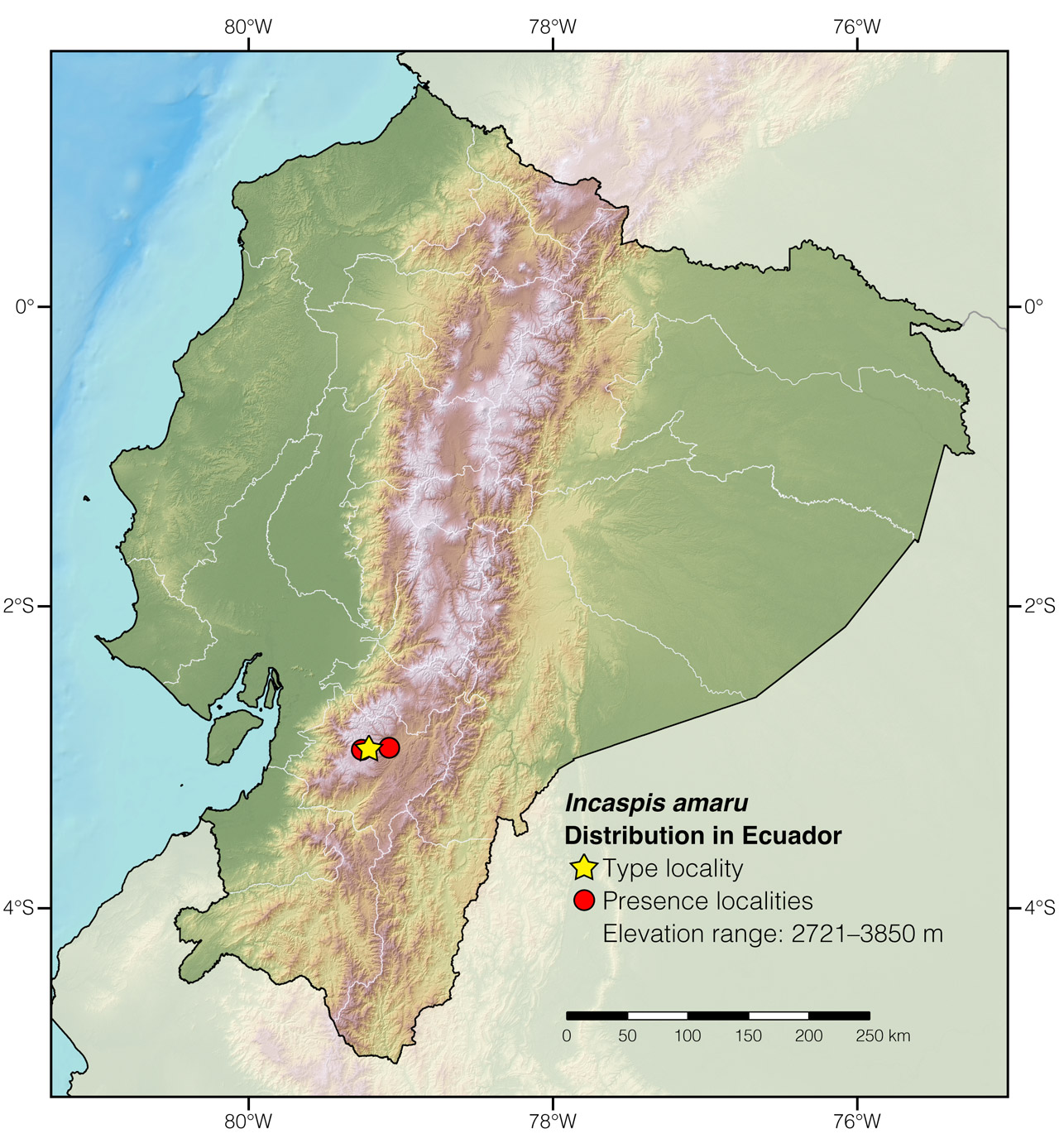

Distribution: Incaspis amaru is endemic to an area of approximately 12 km2 along the valley of the Río Yanuncay, Azuay province, Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Incaspis amaru in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Finca de Manuel Merchán, Azuay province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The genus name Incaspis is a combination of the Quechua word Inca (=royalty) and the Greek word aspis (=venomous snake), in reference to the Inca Empire.5 The specific epithet amaru means “snake” in Ecuadorian Kichwa dialect. According to the Kichwa, Amaru is a mythical serpent that controls water and allows the existence of Andean peoples.1

See it in the wild: Hot Spring Racers can be seen at a rate of about once every few days during sunny mornings at the type locality, Termas Pumamaqui. Individuals seem to be more abundant among tall grass immediately around the hot springs.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Hot Spring Racer (Incaspis amaru). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/LGHC3329

Literature cited:

- Zaher H, Arredondo JC, Valencia JH, Arbeláez E, Rodrigues MT, Altamiro-Benavides M (2014) A new Andean species of Philodryas (Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae) from Ecuador. Zootaxa 3785: 469–480. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3785.3.8

- Arbeláez Ortiz E, Vega Toral A (2008) Guía de anfibios, reptiles, y peces del Parque Nacional Cajas. ETAPA, Cuenca, 155 pp.

- Sánchez Nivicela JC, Urgilés Peñafiel VL, Quezada Riera AB, Timbe Borja, BA, Neira Salamea KD, Siddons DC (2018) Guía de Reptiles de Cuenca. GAD Cuenca y Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, 112 pp.

- Sánchez J (2021) Incaspis amaru. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-2.RLTS.T89928586A89928589.en

- Arredondo JC, Grazziotin FG, Scrocchi GJ, Rodrigues MT, Bonatto SL, Zaher H (2020) Molecular phylogeny of the tribe Philodryadini Cope, 1886 (Dipsadidae: Xenodontinae): rediscovering the diversity of the South American racers. Papéis Avulsos de Zoologia 60: e20206054. DOI: 10.11606/1807-0205/2020.60.54

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Incaspis amaru in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Baños de Cuenca | Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Finca de Manuel Merchán* | Zaher et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Soldados | Arbeláez & Vega-Toral 2008 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Termas Pumamaqui | This work; Fig. 1 |