Published November 17, 2020. Updated April 27, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Olive Marsh-Snake (Erythrolamprus fraseri)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Erythrolamprus fraseri

English common names: Olive Marsh-Snake, Fraser’s Marsh-Snake.

Spanish common names: Culebra pantanera olivácea, culebra de Fraser.

Recognition: ♂♂ 66.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 69 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=54 cm.. Erythrolamprus fraseri is a medium-sized snake having an olivaceous, olive brown, or grayish dorsal coloration with thin black stripes along the posterior half of the body and tail (Fig. 1).1 Individuals of this species are distinguished from other greenish Andean diurnal snakes in southern Ecuador (particularly Chironius monticola, Dendrophidion brunneum, Leptophis occidentalis, and Mastigodryas heathii) by being smaller (total length <1 m), having contrasting black stripes on the body (not only on the tail), and by having black-checkered yellow ventral surfaces. This species differs from E. albiventris by having a blotched, instead of immaculate yellow, venter.1 Young individuals of E. fraseri usually have a black nape band.

Figure 1: Individuals of Erythrolamprus fraseri from Ecuador: Guachapala, Azuay province (); Azogues, Cañar province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Erythrolamprus fraseri is a diurnal and terrestrial snake that inhabits montane shrublands, grasslands, evergreen montane forests, and areas having a matrix of pastures, plantations, rural gardens, and remnants of native vegetation.2–4 This species is also semi-aquatic, occurring in higher densities in marshes, swamps, and along streams.3,5 Olive Marsh-Snakes are typically seen active during sunny mornings, basking in open areas or foraging on leaf-litter, mud, or among tall grass.2–4 When not active, they hide under trunks.5 Olive Marsh-Snakes are active hunters of amphibians. Their dentition is aglyphous,6 meaning their teeth lack specialized grooves to deliver venom. Their diet is based primarily on frogs (including Gastrotheca cuencana, Pristimantis lutzae, and P. lymanni), and tadpoles of Gastrotheca.3,7 Individuals are usually calm and try to flee when threatened, relying mostly on crypsis as a primary defense mechanism. If disturbed, they may flatten their body dorsoventrally and produce a musky and distasteful odor.2

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. The status of Erythrolamprus fraseri has not yet been formally assessed by the IUCN. In this account, the species is proposed to be assigned to the Near Threatened category given that its wide distribution precludes it from being included in a threatened category.8 The main threat to the long-term survival of populations of E. fraseri is the continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat, mostly due to encroaching human activities such as agriculture, cattle grazing, wild fires, and the replacement of native vegetation with eucalyptus and pine trees. It is estimated that in Ecuador, ~56.2% of the natural habitat of the species has already been destroyed.9 Olive Marsh-Snakes also suffer from traffic-related mortality.4 Therefore, the species may qualify for a threatened category in the near future if these threats are not addressed. However, there is no current information on the population trend of E. fraseri to determine whether its numbers are declining.

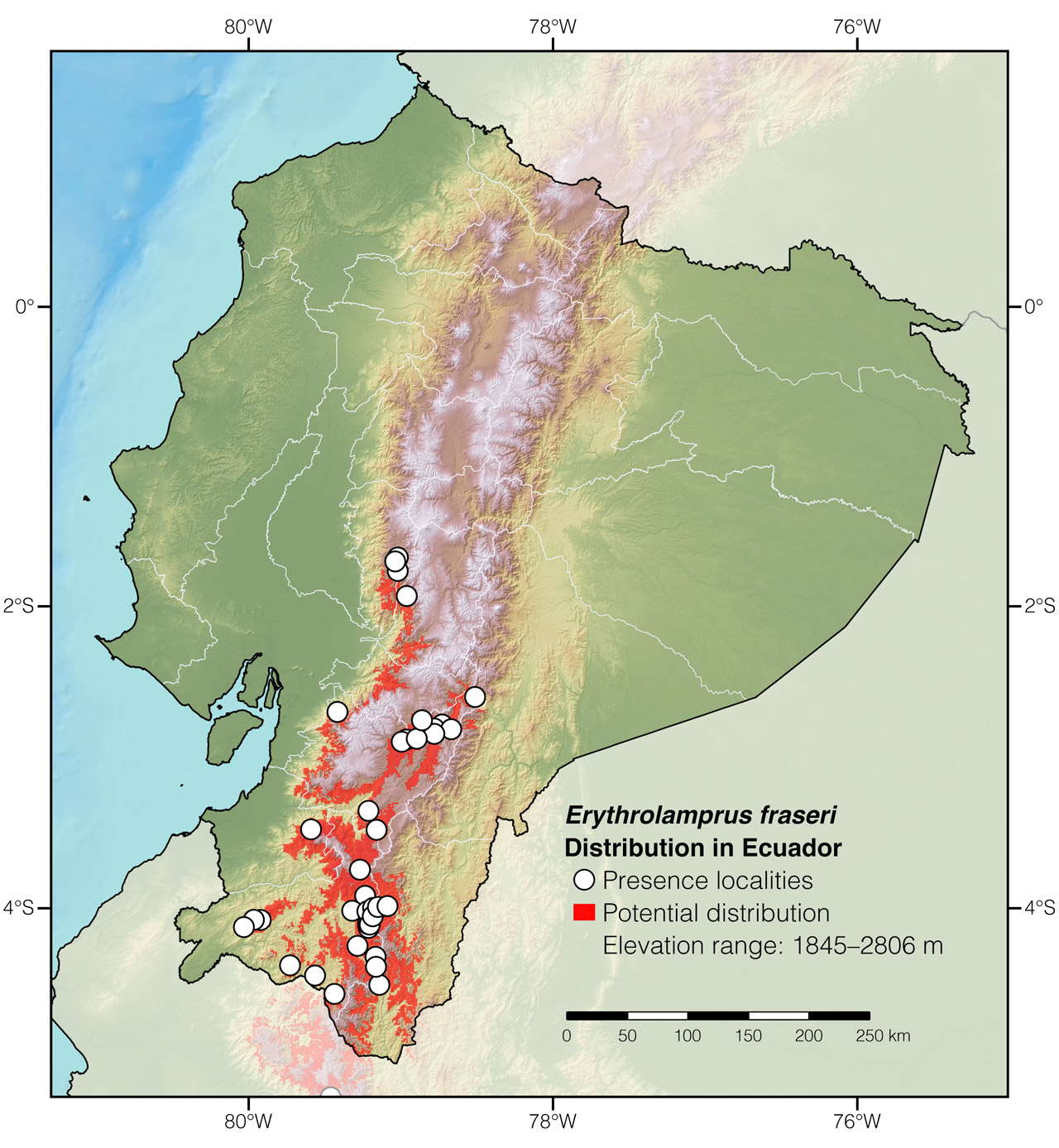

Distribution: Erythrolamprus fraseri is native to the inter-Andean valleys and both slopes of the Andes from southern Ecuador (Fig. 2) to central Perú.1

Figure 2: Distribution of Erythrolamprus fraseri in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Erythrolamprus, which comes from the Greek words erythros (=red) and lampros (=brilliant),10 refers to the bright red body rings of some snakes in this genus (such as E. aesculapii). The specific epithet fraseri honors Louis Fraser, a British zoologist and naturalist who collected the holotype.11

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Olive Marsh-Snakes are recorded usually no more than once a week at any given locality. However, in areas having low vehicle traffic, such as along the Sendero Caxarumi, Loja province, individuals may be seen more frequently. The snakes may be spotted as they cross trails and roads in areas of highland shrubland, especially during the early morning.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Amanda Quezada, Ernesto Arbeláez, Jose Manuel Falcón, and Pablo Loaiza for providing locality data and natural history information for Erythrolamprus fraseri. This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Special thanks to Dr. Robert A. Thomas for symbolically adopting the Olive Marsh-Snake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Frank PichardoaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Olive Marsh-Snake (Erythrolamprus fraseri). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/XXDZ6274

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR (1983) Systematics of the Latin American snake Liophis epinephelus (Serpentes: Colubridae). In: Rhodin AGJ, Miyamata K (Eds) Advances in herpetology and evolutionary biology. Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, 132–149.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm.

- Darwin Núñez, pers. comm.

- Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm.

- Hurtado-Gómez JP (2016) Systematics of the genus Erythrolamprus Boie 1826 (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) based on morphological and molecular data. PhD thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 62 pp.

- Pablo Loaiza, pers. comm.

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1894) Catalogue of the snakes in the British Museum (Natural History). British Museum of Natural History, London, 382 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Erythrolamprus fraseri in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Challuabamba | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Cuenca | Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | El Progreso | Jorge Luis Romero, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Guachapala | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Guarumales | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Luz María | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Oña | Pablo Loaiza, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Paute | Ernesto Arbeláez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Sevilla de Oro | USNM 232831; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Uzhupud | MZUA.RE.0050; examined |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Vía a Jadán | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Guaranda, 7.5 km S of | KU 202952; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | Río Tatahuazo | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Ecuador | Bolívar | San José de Chimbo | AMNH 17498; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Cañar | Azogues | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | San Vicente de Asacoto | Almendáriz & Orcés 2004 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Chilla | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Abra de Zamora | KU 202953; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cajanuma | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Catamayo, on way to Loja | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Loja | Caxarumi | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Loja | Celica, 10 km N of | Dixon 1983 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Curishiro | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja | AMNH 22095; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja–Cajanuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 12 km S of | Dixon 1983 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 3 km E of | USNM 232833; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 7 km N of | Dixon 1983 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Madrigal del Podocarpus | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Malacatos, cerros | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Loja | Masaconsa | MCZ 93590; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Pindal, on way to Celica | Jose Manuel Falcón, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Loja | Reserva Tapichalaca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | San José de Macará | MZUA.RE.0079; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | San Lucas | Field notes of Felipe Campos |

| Ecuador | Loja | San Ramón | Dixon 1983 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Utuana | Yánez-Muñoz & Morales-Mite 2013 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Via antigua Loja–Zamora | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Ecuador | Loja | Yangana, 3 km SE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Estación San Francisco | MZUA.RE.0149; examined |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Cerro Laguna Seca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Canchaque, 15 km E of | Dixon 1983 |

| Perú | Piura | Cruz Blanca | Torres-Carvajal & Hinojosa 2020 |

| Perú | Piura | Huancabamba | Dixon 1983 |