Published April 3, 2022. Updated May 16, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Desert Tropical-Racer (Mastigodryas heathii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Mastigodryas heathii

English common names: Desert Tropical-Racer, Heath’s Tropical Racer.

Spanish common names: Sayama, corredora tropical de desierto.

Recognition: ♂♂ 97.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=70.9 cm. ♀♀ 122.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=87.8 cm..1–3 Tropical Racers (genus Mastigodryas) can be identified from other medium-sized diurnal snakes in Ecuador by having a loreal scale, more than one anterior temporal scale, and smooth dorsal scales arranged in 17 rows at mid-body.4–6 Juveniles of M. heathii are easily identified based on their ornate dorsal coloration, which consists of dark-brown crossbars on a lighter background shade (Fig. 1).1 In adults, this pattern gradually disappears and is replaced by a uniform grayish-brown dorsum with two broad (3 dorsal scales wide) and pale dorsolateral stripes.1–4 Mastigodryas heathii approaches the distribution of, and may even co-occur with, M. pulchriceps and M. reticulatus. While juveniles of the three species are difficult to tell apart, adults are easily distinguishable. Those of M. pulchriceps have thinner (1-scale wide) dorsolateral stripes than adults of M. heathii.4 Adults of M. reticulatus lack a striped pattern; instead, they have a uniform grayish dorsum in which each scale is edged in black.4 Other snakes similar in size and coloration that may be found living alongside M. heathii in Ecuador are Pseudalsophis elegans, which has 19 dorsal scale rows at mid-body and lacks dorsolateral stripes,7 and Dendrophidion brunneum, which has some rows of dorsal scales keeled (all smooth in Mastigodryas).5

Figure 1: Individuals of Mastigodryas heathii from Ecuador: Alamor, Loja province (); unknown locality (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Mastigodryas heathii is a diurnal and primarily terrestrial snake that inhabits open xeric ecosystems,1 including seasonally dry forests and shrublands.2,4 The species also occurs in areas having a matrix of pastures, plantations, and remnants of native vegetation.1,2,8 Desert Tropical-Racers are active during the daytime. Individuals have been seen crossing roads and trails, basking in the open, creeping on sandy walls,3 or frantically foraging on leaf-litter, soil, or on shrubs up to 1.5 m above the ground.1,2,9 At night, they sleep on bushes up to 3 m above the ground.2,10 Racer snakes in general are opisthoglyphous (having enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla) and mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.11,12 Desert Tropical-Racers are active hunters and their diet is based on lizards (including Stenocercus imitator1), frogs (Pristimantis lymanni2), and rodents.1,13 These snakes rely mostly on crypsis as a primary defense mechanism; when threatened, they usually try to flee. However, if grabbed or cornered, these agile serpents will not hesitate to strike.1,2 They may also shed portions of their tail as a method of escape.4 One female of M. heathii from Perú contained six leathery-shelled oviductal eggs,4 but the real clutch size is not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..8 Mastigodryas heathii is included in this category on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, lack of major widespread threats, and presumed stable populations.8 The main threat to the long-term survival of some populations of M. heathii is the continuing decline in the extent and quality of its habitat, mostly due to encroaching human activities such as agriculture, cattle grazing, wild fires, and the replacement of native vegetation with eucalyptus and pine trees. In Ecuador, the species has been classified as Critically Endangered14 because nearly 54% of its potential habitat has already been destroyed in this country.15 Desert Tropical-Racers also suffer from traffic-related mortality and human persecution. Local residents kill individuals of M. heathii and use their fat bodies for medicinal purposes.8

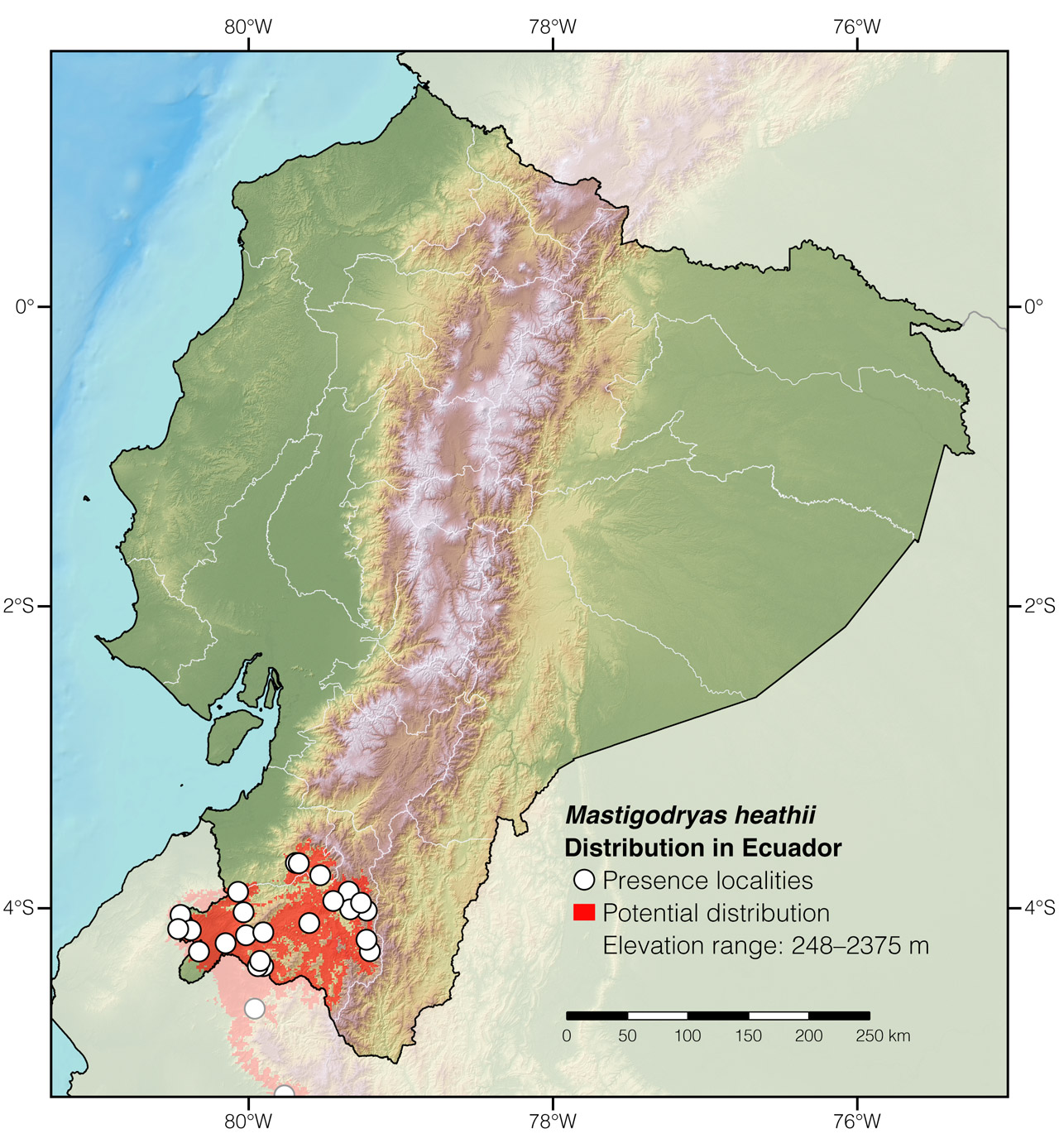

Distribution: Mastigodryas heathii is native to the Tumbesian lowlands and adjacent Andean slopes of extreme southwestern Ecuador (provinces El Oro and Loja; Fig. 2) and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Mastigodryas heathii in Ecuador. The type locality, Valley of Jequetepeque, is not shown in the map. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Mastigodryas, which comes from the Greek words mastigos (=whip) and dryas (a tree-nymph),16 refers to the long whip-like tail in snakes of this genus. The specific epithet heathii honors Dr. Edwin Ruthven Heath (1839–1932), an American traveler and physician who collected the holotype of the species.17

See it in the wild: Individuals of Mastigodryas heathii may be encountered at rate of about once every week in some areas throughout the species’ distribution. Desert Tropical-Racers are particularly abundant in Jorupe Reserve and La Ceiba Reserve. The snakes may be seen as they cross trails and roads in areas having adequate vegetation cover, especially during sunny mornings.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Desert Tropical-Racer (Mastigodryas heathii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/GOGA9722

Literature cited:

- Cadle JE (2012) Rediscovery of the holotype of Mastigodryas heathii (Cope) (Serpentes: Colubridae) and additional notes on the species. South American Journal of Herpetology 7: 16–24. DOI: 10.2994/057.007.0102

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Koch C (2013) The Herpetofauna of the Peruvian dry forest along the Andean valley of the Marañón River and its tributaries, with a focus on endemic iguanians, geckos and tegus. PhD thesis, Bonn, Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 264 pp.

- Montingelli GG, Valencia JH, Benavides MA, Zaher H (2011) Revalidation of Herpetodryas reticulata (Peters, 1863) (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Ecuador. South American Journal of Herpetology 6: 189–197. DOI: 10.2994/057.006.0304

- Peters JA, Orejas-Miranda B (1970) Catalogue of Neotropical Squamata: part I, snakes. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 347 pp.

- Montingelli GG (2009) Revisão taxonômica do gênero Mastigodryas Amaral, 1934 (Serpentes: Colubridae). PhD thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 338 pp.

- Myers CW, Hoogmoed MS (1974) Zoogeographic and taxonomic status of the South American snake Tachymenis surinamensis (Colubridae). Zoologische Mededelingen 48: 187–194.

- Venegas P, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Lehr E, Yánez-Muñoz M (2016) Mastigodryas heathii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T176860A50867108.en

- Acosta Vásconez AN (2014) Diversidad y composición de la comunidad de reptiles del Bosque Protector Puyango. BSc thesis, Universidad San Francisco de Quito, 157 pp.

- Photo by Bryan Suson.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Guzmán R (2010) Secretos de los reptiles. Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, 137 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011) The eponym dictionary of reptiles. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 296 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Mastigodryas heathii in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Bosque Petrificado de Puyango | Acosta 2014 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Cerro Pata Grande | This work |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Villa Elvita | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Zaruma, 15 km S of | USNM 211055 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Alamor | This work |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cabañas Río Yambala | Field notes of Andrew Gluesenkamp |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cabeza de Toro | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Catanas, 6 km SW of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cazaderos | Photo by Santiago Hualpa |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cerro Negro | Vázquez et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Chantaco | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cruzpamba, 1.6 km S of | MCZ 93586 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Jorupe Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Loja | Km 10 Catacocha–Playas | Photo by Pablo Loaiza |

| Ecuador | Loja | La Zanja | MUTPL-R 9 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 23 km W of | IDIGBIO 116498 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja, 7 km N of | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Macará | Photo by David Salazar |

| Ecuador | Loja | Macará, 5 km N of | This work |

| Ecuador | Loja | Mangahurco | Photo by Fausto Siavichay |

| Ecuador | Loja | Quebrada Cañaberal | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Quinta La Sexta | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Loja | San Pedro | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Jaén, 9 km S of | LSUMZ 19628 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Pacopamba | MCZ 183597 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Perico | Koch et al. 2014 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Río Zaña | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Santa Rosa de la Yunga | Koch et al. 2014 |

| Perú | Piura | Bosque Seco de Yacila de Zamba | Vásquez Calle 2015 |

| Perú | Piura | Carretera Sullana–Lancones | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Querpón, 21 km N of | LSUMZ 35250 |