Published March 29, 2022. Updated May 16, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Reticulated Tropical-Racer (Mastigodryas reticulatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Mastigodryas reticulatus

English common name: Reticulated Tropical-Racer.

Spanish common name: Serpiente látigo reticulada.

Recognition: ♂♂ 161.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=125.7 cm. ♀♀ 173.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=144.7 cm..1 Tropical Racers (genus Mastigodryas) can be identified from other medium-sized diurnal snakes in Ecuador by having a loreal scale, more than one anterior temporal scale, and smooth dorsal scales arranged in 17 rows at mid-body.2,3 Juveniles of M. reticulatus are easily identified based on their ornate dorsal coloration, which consists of dark-brown blotches on a lighter background shade. In adults, this pattern gradually disappears and is replaced by a uniform grayish dorsum in which each scale is edged in black (Fig. 1).1 The anterior 1/8 of the body in adults has a brighter olivaceous hue.1 Mastigodryas reticulatus approaches the distribution of, and may even co-occur with, M. heathii and M. pulchriceps. While juveniles of the three species are difficult to tell apart, adults are easily distinguishable. Those of M. heathii have conspicuously broad (3 dorsal scales wide) dorsolateral stripes, which, in adults of M. reticulatus, are thin, indistinct, or absent.1 Adults of M. pulchriceps differ from those of M. reticulatus by lacking black-edged dorsal scales.4 Other snakes similar in size and coloration that may be found living alongside M. reticulatus in Ecuador are Erythrolamprus albiventris, which has one anterior temporal scale (instead of two),4 and Dendrophidion brunneum, which has keeled (instead of smooth) dorsal scales.2

Figure 1: Individuals of Mastigodryas reticulatus from Chongón, Guayas province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Mastigodryas reticulatus is a diurnal and primarily terrestrial snake that inhabits xeric ecosystems near the coast, including seasonally dry forests, savannas, and shrublands.1,5 The species also occurs in areas having a matrix of pastures, plantations, and remnants of native vegetation, as well as in gardens of heavily-populated urban areas.5 Snakes of this species are active during the sunniest hours of the day, frantically foraging on leaf-litter, soil, or among grass or shrubs.5 At night, they sleep on bushes.6 Racer snakes in general are opisthoglyphous (having enlarged teeth towards the rear of the maxilla) and mildly venomous, which means they are dangerous to small prey, but not to humans.7,8 Reticulated Tropical-Racers are active hunters and their diet is probably largely based on lizards, but only one species, Dicrodon guttulatum,9 has been formally confirmed as a prey item. These snakes rely mostly on crypsis as a primary defense mechanism; when threatened, they usually try to flee. However, if grabbed or cornered, these agile serpents will not hesitate to strike.5 There is an unpublished record of a Laughing Falcon (Herpetotheres cachinnans) preying upon an individual of this species in Portoviejo, Manabí province.10 Snakes in the genus Mastigodryas are oviparous,8 but there is no information about the clutch size in M. reticulatus.

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..6 Mastigodryas reticulatus is included in this category because although the species is widely distributed and tolerates moderate habitat degradation, its populations are fragmented and occur over an area where approximately 43% of the forest cover has been transformed into pastures, plantations, and human settlements.6,11 Furthermore, snakes of this species suffer from intense persecution and traffic-related mortality.5 Therefore, M. reticulatus may qualify for a threatened category in the near future if these threats are not addressed. There is no current information on the population trend of the Reticulated Tropical-Racer to determine whether its numbers are declining. Fortunately, the species has been registered in five protected areas in Ecuador.

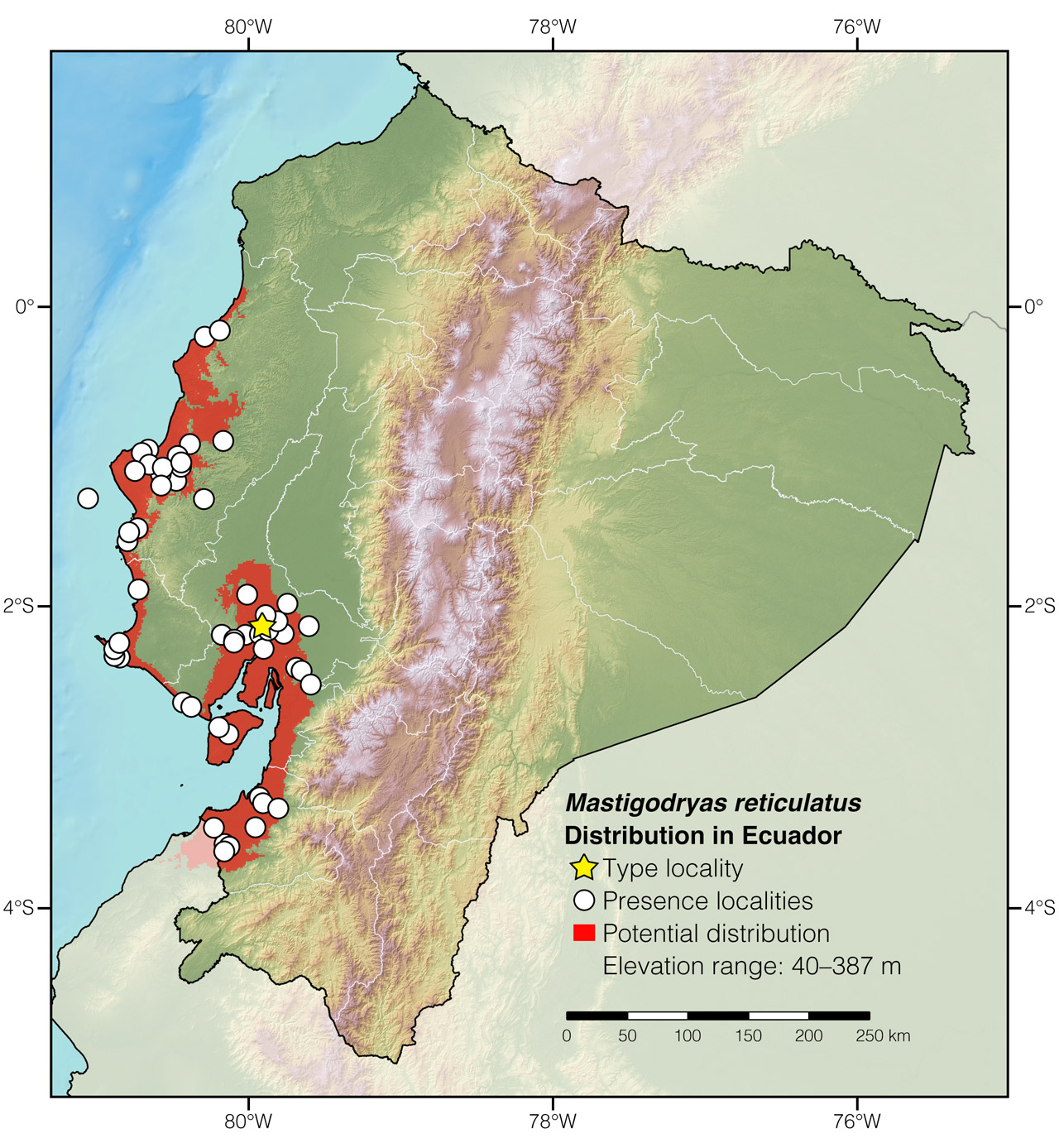

Distribution: Mastigodryas reticulatus is endemic to an area of approximately 18,850 km2 along the Tumbesian lowlands of western Ecuador, including La Plata and Puná islands (Fig. 2). The species also likely occurs in neighboring Peru, but probably not in the inter-Andean valleys of the Río Marañón, where an isolated population assignable to this species has been reported.12

Figure 2: Distribution of Mastigodryas reticulatus in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Gulf of Guayaquil, Pichincha province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Mastigodryas, which comes from the Greek words mastigos (meaning “whip”) and dryas (a tree-nymph),13 refers to the long whip-like tail in snakes of this genus. The specific epithet reticulatus is a Latin word meaning “net pattern.”13 It probably refers to the dorsal color pattern, in which the thin black edges of each scale overlap and form a faint reticulation.

See it in the wild: Individuals of Mastigodryas reticulatus may be encountered at rate of about once every week in some areas throughout the species’ distribution. Reticulated Tropical-Racers are particularly abundant in forested areas around the cities of Guayaquil, Manta, and Portoviejo. They are also frequently spotted in Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco and Machalilla National Park. The snakes may be seen as they cross trails and roads in areas having adequate vegetation cover, especially during sunny mornings.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Gonzalo Pazmiño for finding the specimens photographed in this account.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2022) Reticulated Tropical-Racer (Mastigodryas reticulatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/OOLU4066

Literature cited:

- Montingelli GG, Valencia JH, Benavides MA, Zaher H (2011) Revalidation of Herpetodryas reticulata (Peters, 1863) (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Ecuador. South American Journal of Herpetology 6: 189–197. DOI: 10.2994/057.006.0304

- Peters JA, Orejas-Miranda B (1970) Catalogue of Neotropical Squamata: part I, snakes. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 347 pp.

- Montingelli GG (2009) Revisão taxonômica do gênero Mastigodryas Amaral, 1934 (Serpentes: Colubridae). PhD thesis, Universidade de São Paulo, 338 pp.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Valencia J, Brito J, Yánez-Muñoz M, Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Venegas P (2014) Mastigodryas reticulatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T50950871A54447684.en

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Brennan R (2010) Un estudio ecológico de las lagartijas del valle seco de Buenavista y de los valles húmedos de La Josefina y Salango. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection, Vermont, 828 pp.

- Photo by Lisa Brunetti.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Koch C (2013) The Herpetofauna of the Peruvian dry forest along the Andean valley of the Marañón River and its tributaries, with a focus on endemic iguanians, geckos and tegus. PhD thesis, Bonn, Rheinischen Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn, 264 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Mastigodryas reticulatus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Cacarbon | DHMECN 11533 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Destacamento Montúfar | EPN-H 13075 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Hualtaco | USNM 211056 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Machala | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Machala, 7 km ESE of | USNM 211055 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Pasaje | AMNH 22098 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Ecológica Arenillas | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Rosa | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Belén | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Bosque Protector Cerro Blanco | This work |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Campo Alegre, Isla Puná | CAS 8802 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Capeira | Photo by Eduardo Zavala |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro Masvale | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro Pancho Diablo | This work |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro Paraíso | Photo by Eduardo Zavala |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Chongón | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Durán | DHMECN 209 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Guayaquil, Av. 25 de Julio | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Gulf of Guayaquil* | Peters 1863 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Puná | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Milagro | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Parque El Lago | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Parque Histórico de Guayaquil | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Playa el Pelado | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Playas Villamil | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Puerto Inca, 6 km NW of | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Recinto San Jose | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Sambocity | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Vía Daule–Samborondón | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Bolívar | DHMECN 11666 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cabuyal | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Colón, 5 km W of | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Cardón | DHMECN 11648 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Hills of Puerto López | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Isla de la Plata | This work |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jaramillo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Pila | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Manta | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Mejía | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Montecristi | DHMECN 11668 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Parque Las Vegas | Photo by Lisa Brunetti |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Parque Nacional Machalilla | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Playa Los Frailes | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Portoviejo, 11 km W of | Montingelli et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Portoviejo, La Tomatera | Photo by Lisa Brunetti |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Punta Prieta, 5 km SE of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Quimis | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Manta | Photo by Juan Carlos Sánchez |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Visquije | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Ancón | IDIGBIO 1931.10.21.11 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Anconcito | IDIGBIO 1931.10.21.9 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Represa Velasco Ibarra | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Santa Elena | This work |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Santa Elena, 50 km N of | IDIGBIO 116502 |