Published January 14, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Perú Desert-Tegu (Dicrodon guttulatum)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Teiidae | Dicrodon guttulatum

English common name: Perú Desert-Tegu.

Spanish common name: Cañán.

Recognition: ♂♂ 55.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=16.3 cm. ♀♀ 46.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=13.6 cm..1,2 Dicrodon guttulatum differs from other lizards in its area of distribution by having small granular dorsal scales, large squarish ventral scales, and a large entire frontal scale.1,3 In Holcosus and Callopistes, the frontal area is covered by many small scales.1 Dicrodon guttulatum differs from Medopheos edracanthus by having obliquely arranged parietal scales and a different coloration.1,2 Both adults and juveniles of the Perú Desert-Tegu have cream dots on a light brown dorsum. Juveniles and adult females have light dorsolateral lines and a white throat (Fig. 1), whereas adult males boast a bright blue head, cyan ventral surfaces, and a reddish hue on the back.4

Figure 1: Juvenile of Dicrodon guttulatum from La Ceiba Reserve, Loja province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Dicrodon guttulatum is a diurnal and terrestrial lizard adapted to living in deserts, dry shrublands, and dry forests,4 occurring in lower densities in human-modified habitats such as crops and rural gardens.5 The species is gregarious, living in colonies of 10–20 individuals around a system of burrows, which are holes in sandy soil that may be interconnected.4,6 Perú Desert-Tegus prefer open areas with direct access to sunlight,6 being active only during hot, sunny hours.5 They forage frantically, essentially never stopping as they search for food, never too far from vegetation cover.5 As soon as sunlight wanes, they retreat into their burrows.4 Their diet is almost exclusively herbivorous (78–100%) and includes shoots, tender fruits, and seeds of at least eight plant species.4,7,8 Between 12 and 95% of the diet is based on a single plant, Prosopis pallida, a tree and shrub that provides lizards with forage, basking sites, and protection.9 Insects usually represent no more than 16% of the total volume of prey items consumed.6,8 Individuals of D. guttulatum are notably skittish, maintaining a vigilant watch for potential predators. Their primary defense mechanisms are alertness and rapid sprinting, though they may run into their burrows or climb to low vegetation to avoid predators.5,6 There are documented instances of predation on individuals of this species by snakes (Mastigodryas reticulatus6 and Porthidium arcosae10,11) and lizards (Callopistes flavipunctatus).12 Males of D. guttulatum are territorial, chasing away other large breeding males from the colony.6 A gravid female from Perú contained four oviductal eggs,13 but the real clutch size is not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..14 Dicrodon guttulatum is listed in this category primarily on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, high population densities, and presence in protected areas.14 Unfortunately, habitat loss and fragmentation are ongoing across more than a third of the distribution and the species has reportedly declined or been extirpated from some localities.14 Current threats include the widespread cultivation of rice crops, rural-urban development,4,14 vehicular traffic,15 and subsistence hunting.9

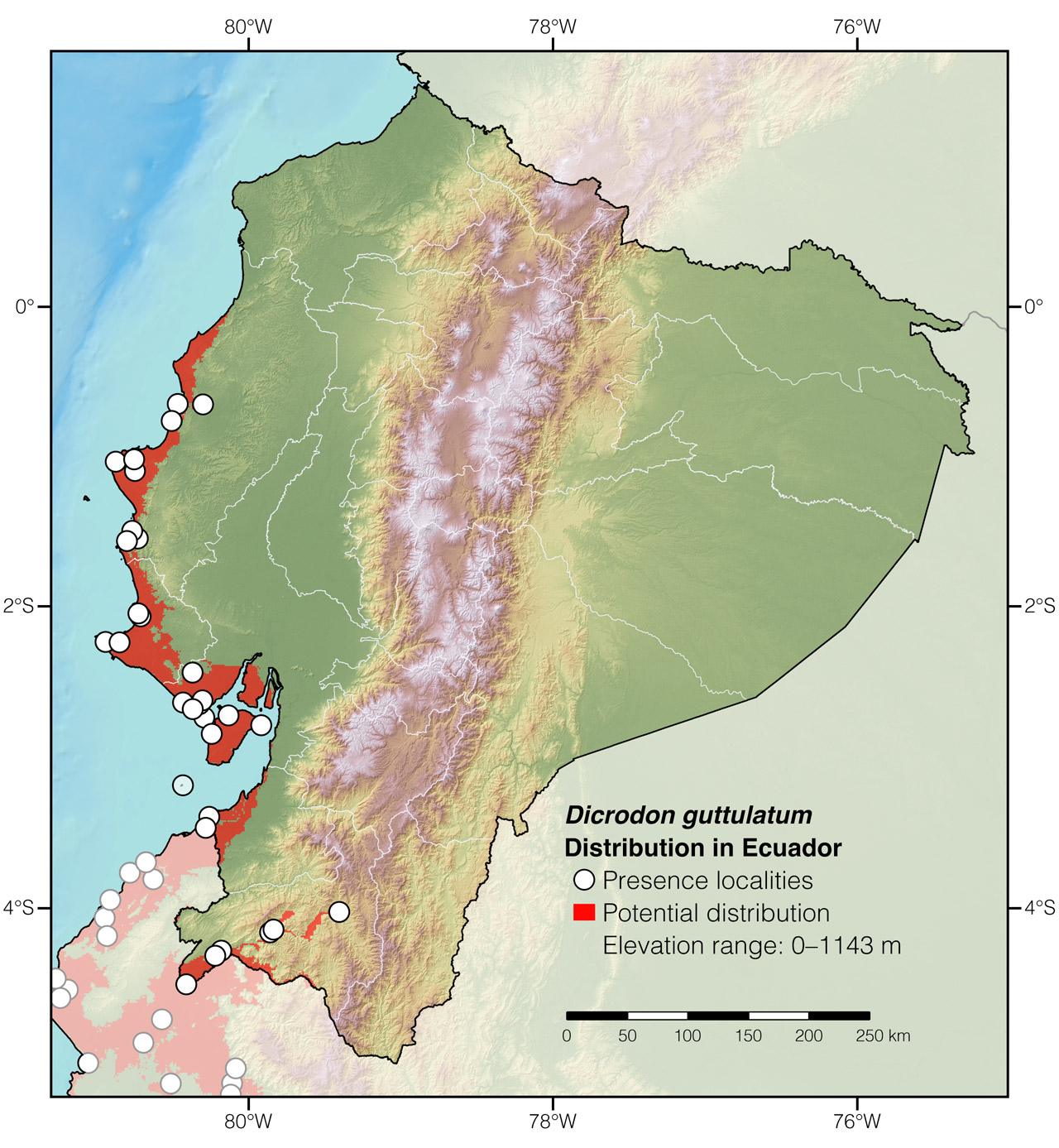

Distribution: Dicrodon guttulatum is native to the Tumbesian lowlands of western Ecuador (Fig. 2) and northwestern Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Dicrodon guttulatum in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Dicrodon is derived from the Greek dikros (=forked) and odontos (=teeth).16 The name refers to the bifid posterior teeth.1 The specific epithet guttulatum comes from the Latin guttula (=droplet) and the suffix -atum (=provided with).16 This refers to the dorsal coloration, which is “dotted with white droplets.”17

See it in the wild: Perú Desert-Tegus are virtually guaranteed sightings within their distribution range in Ecuador, especially in Machalilla National Park and La Ceiba Reserve. These are extremely jittery reptiles best captured using pitfall traps with drift fences.2

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Perú Desert-Tegu (Dicrodon guttulatum). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/JCUZ5011

Literature cited:

- Harvey MB, Ugueto GN, Gutberlet Jr RL (2012) Review of teiid morphology with a revised taxonomy and phylogeny of the Teiidae (Lepidosauria: Squamata). Zootaxa 3459: 1–156. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3459.1.1

- Gutiérrez de la Cruz GL (2018) Situación taxonómica de Dicrodon guttulatum Duméril & Bibron, 1839 y Dicrodon holmbergi Schmidt, 1957 (Sauria: Teiidae): estudio morfológico, morfométrico y hemipeniano. BSc thesis, Lima, Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, 93 pp.

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- García-Bravo A, Guzman BK, Mendoza JE, Torres Guzmán C, Oliva M, Barboza E, Quiñones Rámirez J, Zabarburu-Veneros JL, Venegas PJ (2022) Updating the distribution of Dicrodon guttulatum Duméril & Bibron, 1839 (Reptilia, Teiidae) with a disjunct population in the eastern slope of the Peruvian Andes. Check List 18: 483–491. DOI: 10.15560/18.3.483

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Brennan R (2010) Un estudio ecológico de las lagartijas del valle seco de Buenavista y de los valles húmedos de La Josefina y Salango. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection, Vermont, 828 pp.

- Pollack Velásquez L, Zelada Estraver W, Tirado Pinedo A, Pollack Chinchay L (2007) Hábitos alimentarios de Dicrodon guttulatum “cañán” (Squamata: Teiidae) en Garrapón, Paiján Eating. Arnaldoa 14: 283–291.

- van Leeuwen J, Catenazzi A, Holmgren M (2011) Spatial, ontogenetic, and sexual effects on the diet of a teiid lizard in arid South America. Journal of Herpetology 45: 472–477. DOI: 10.1670/10-154.1

- Holmberg AR (1957) Lizard hunts on the north coast of Peru. Fieldiana Anthropology 36: 203–220.

- Acosta-Vásconez N, Carrera M, Peñaherrera E, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2018) Predation on the teiid lizard Dicrodon guttulatum Duméril and Bibron, 1839 by the pitviper Porthidium arcosae Schätti and Kramer, 1993. Herpetology Notes 11: 391–393.

- Valencia JH, Vaca-Guerrero GV, Garzón K (2011) Natural history, potential distribution and conservation status of the Manabi Hognose Pitviper Porthidium arcosae (Schätti & Kramer, 1993), in Ecuador. Herpetozoa 23: 31–43.

- Crespo S, Koch C (2015) Notes on natural history and distribution of Callopistes flavipunctatus (Squamata: Teiidae) in northwestern Peru. Salamandra 51: 57–60.

- Goldberg SR (2008) Notes on reproduction of Dicrodon guttulatum, D. heterolepis and D. holmbergi (Squamata: Teiidae) from Peru. Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society 44: 103–106.

- Perez J, Yánez-Muñoz M, Venegas P, Cisneros-Heredia DF (2017) Dicrodon guttulatum. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T48444161A48444171.en

- Hurtado Ordinola LJ (2021) Especies de fauna silvestre muertas por atropellamiento en la carretera Sullana–Lancones, Piura, Perú. BSc thesis, Piura, Universidad Nacional de Piura, 112 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron G (1839) Erpétologie générale ou Histoire Naturelle complète des Reptiles. Librairie Encyclopédique de Roret, Paris, 871 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dicrodon guttulatum in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Isla San Gregorio | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Between El Prado and Buenos Aires | MCZ 83129; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Data de Posorja | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Limbo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Morro | MCZ 83137; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Progreso | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Puná, Subida Alta | Navarrete 2011 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Santa Clara | Garzón-Santomaro et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Playa el Pelado | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Puerto del Morro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Villamil | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Catamayo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | El Empalme | USNM 164222; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Loja | Fertiles del Sur | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | La Ceiba | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Loja | Lucarqui | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Agua Blanca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Liguiqui | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Machalilla | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Puerto López | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Punta Gorda | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Manta | Photo by Juan Carlos Sánchez |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Salinas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | San Clemente | USNM 201528; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Manabí | San Juan de Manta | Acosta-Vásconez et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Colonche, 6 km SW of | USNM 164242; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Palmar | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Salinas | UIMNH 54554; collection database |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Santa Elena | AMNH 21840; VertNet |

| Perú | Piura | Batanes | Crespo & Koch 2015 |

| Perú | Piura | Cabo Blanco | García-Bravo et al. 2022 |

| Perú | Piura | Caserío el Progreso | García-Bravo et al. 2022 |

| Perú | Piura | Celeste | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Colán | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Lobitos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Palo Blanco | Vásquez Calle 2018 |

| Perú | Piura | Santa Rosa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Sullana, 2 km NE of | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Sullana, 28 km NE of | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Sullana, 64 km NE of | Hurtado Ordinola 2021 |

| Perú | Piura | Talara | FMNH 53856; VertNet |

| Perú | Tumbes | Carretera Mancora-Puntasal | García-Bravo et al. 2022 |

| Perú | Tumbes | Contralmirante Villar | García-Bravo et al. 2022 |

| Perú | Tumbes | El Bendito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | El Rincón | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | Peaje de Canoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | Pedregal, 7 km E of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | Zorritos | García-Bravo et al. 2022 |