Published July 21, 2023. Updated February 8, 2024. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Desert Sticklizard (Macropholidus ruthveni)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gymnophthalmidae | Macropholidus ruthveni

English common names: Desert Sticklizard, Ruthven’s Sticklizard.

Spanish common names: Cuilanpalo de desierto, cuilán de Ruthven.

Recognition: ♂♂ 11.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=3.6 cm. ♀♀ 14.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.6 cm..1 Species of the genus Macropholidus can be identified from other small brownish diurnal lizards by their elongate body with well-developed limbs and by having strongly overlapping sub-rhomboid scales on the sides of the body.1,2 Macropholidus differs from its sister genus Pholidobolus by the presence of a transparent palpebral disc in the lower eyelid.3 Macropholidus ruthveni can be differentiated from its congeners by having smooth (rather than striated or weakly keeled) dorsals and a paired series of enlarged dorsal scale rows along the entire back (restricted to the nape in M. montanuccii and not paired in M. annectens).1,4 The males have ocelli on the shoulders and a reddish coloration along the flanks at the level of the extremities and on the sides of the tail (Fig. 1); females have dull ocelli and do not have a reddish coloration pattern.4

Figure 1: Individuals of Macropholidus ruthveni from La Ceiba Reserve, Loja province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Macropholidus ruthveni is a rarely seen diurnal lizard that occurs in seasonally dry foothill forests as well as in human-modified environments such as along roads, in plantations,1,5 and around golf courses.6 Desert Sticklizards are active especially during sunny hours,7 moving on the ground mainly through leaf-litter.1,8 They occur along watercourses such as streams as well as on moss up to 1.5 m above the ground.1,8 Inactive individuals have been found mostly under rocks and logs or in leaf-litter.1,8 The diet in this species includes invertebrates such as beetles and moths.6 There are records of snakes (Coniophanes longinquus1 and Pseudalsophis elegans6 preying upon individuals of this species. When threatened, Desert Sticklizards usually hide among vegetation, brushy hillsides, under rocks, or beneath tree bark.1,9 If handled they may shed the tail or bite.8 Females deposit clutches of 1–2 eggs1,6 in crevices or under rock piles, either individually or in communal nesting sites.1,6

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..5 Macropholidus ruthveni is listed in this category because the species is common in some localities, it tolerates disturbed environments, and its populations are not expected to decline in the near future.5 Although deforestation due to agricultural expansion is frequent in its area of distribution, this is not considered a major threat to the species.5 Macropholidus ruthveni is found in several protected areas (La Ceiba Nature Reserve, Laquipampa Wildlife Refuge, Cerros de Amotape National Park, and Udima Reserved Zone)5 and is believed to have been introduced in Lima department.6 Thus, the range of this lizard might actually be increasing.

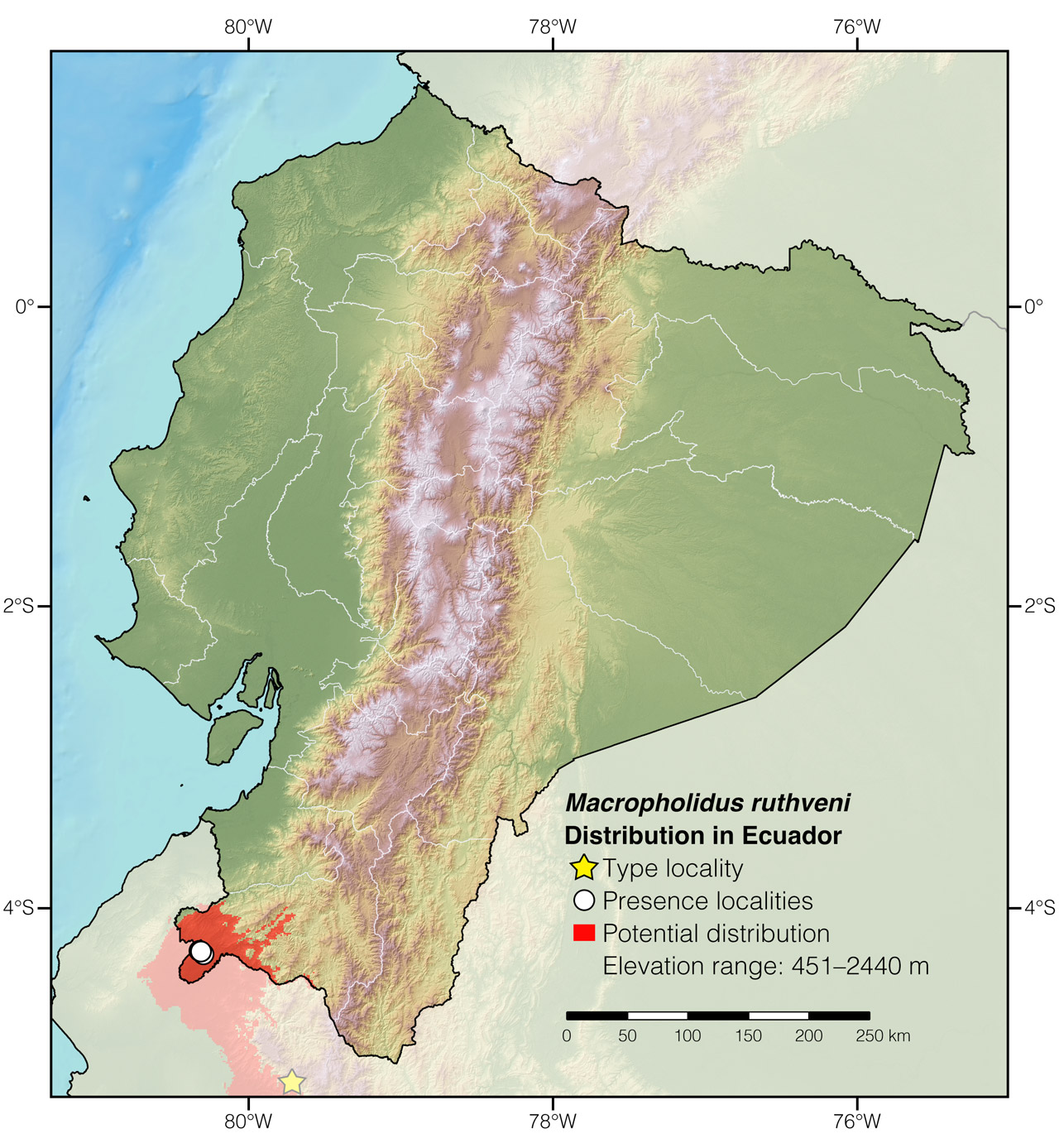

Distribution: Macropholidus ruthveni is distributed in the Tumbesian lowlands and adjacent Andean slopes of southern Ecuador (Loja province) and northwestern Perú (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Macropholidus ruthveni in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Cocumayo, Piura department. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Macropholidus comes from the Greek words makros (=long) and pholidos (=scale),10 and refers to the large scales around the body of these lizards.2 The specific epithet ruthveni honors Alexander Grant Ruthven (1882–1971), former president of the University of Michigan, in recognition of his many contribution to the herpetology of the Americas.2

See it in the wild: Desert Sticklizards are extremely difficult to observe in Ecuador. So far, they have only been recorded in La Ceiba Reserve and their populations there seem to be low. These shy reptiles can be located by scanning sunlit substrates along forest trails during the morning or by searching under rocks and logs at night.

Authors: Amanda QuezadaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jeffrey D CampercAffiliation: Department of Biology, Francis Marion University, Florence, USA.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Quezada A, Arteaga A (2024) Desert Sticklizard (Macropholidus ruthveni). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/RMSA2982

Literature cited:

- Cadle JE, Chuna P (1995) A new lizard of the genus Macropholidus (Teiidae) from a relictual humid forest of northwestern Peru, and notes on Macropholidus ruthveni Noble. Breviora 501: 1–39.

- Noble GK (1920) Some new lizards from northwestern Peru. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 29: 133–139. DOI: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1920.tb55353.x

- Torres-Carvajal O, Venegas P, Lobos SE, Mafla-Endara P, Sales Nunes PM (2014) A new species of Pholidobolus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae) from the Andes of southern Ecuador. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 8: 76–88.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Venegas PJ, Nunes PMS (2020) Description and phylogeny of a new species of Andean lizard (Gymnophthalmidae: Cercosaurinae) from the Huancabamba depression. South American Journal of Herpetology 18: 13–23. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-18-00069.1

- Aguilar C, Lehr E, Venegas P, Suárez J, Lundberg M (2017) Macropholidus ruthveni. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T178410A48282100.en

- Guzmán R (2010) Secretos de los reptiles. Universidad Ricardo Palma, Lima, 137 pp.

- Venegas P (2005) Herpetofauna del bosque seco ecuatorial de Perú: taxonomía, ecología y biogeografía. Zonas Áridas 9: 9–24. DOI: 10.21704/ZA.V9I1.565

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Pittman RAG (2020) Situación actual de Macropholidus ruthveni Noble 1821 en la provincia de Lima. Sagasteguiana 8: 69–70.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Macropholidus ruthveni in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Loja | Cabeza de Toro | MZUA.Re.0363; examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Quebrada seca | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Loja | Reserva La Ceiba | Torres -Carvajal et al. 2015 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Bosque Cachil | Guzmán 2010 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Río Zaña | Cadle & Chuna 1995 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Sangal | Cadle & Chuna 1995 |

| Perú | Chiclayo | Chongoyape | Cadle & Chuna 1995 |

| Perú | La Libertad | Monte Seco | Cadle & Chuna 1995 |

| Perú | Lambayeque | Lambayeque | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Lambayeque | Pomalca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Lima | Chaclacayo | Cadle & Chuna 1995 |

| Perú | Piura | Cocumayo* | Noble 1921 |