Published May 12, 2018. Updated March 30, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Bob Ridgely’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas bobridgelyi)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Dipsas bobridgelyi

English common name: Bob Ridgely’s Snail-eating Snake.

Spanish common name: Caracolera de Bob Ridgely.

Recognition: ♂♂ 67.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=47.8 cm. ♀♀ 56.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=40.4 cm..1 In its area of distribution, Dipsas bobridgelyi is the only snake having a combination of large bulging eyes and a pattern of 29–35 broad black body rings separated from each other by narrow brown-stippled pale interspaces (Fig. 1).1 The head is prominent and boasts a characteristic pattern of scattered whitish, black, and rusty speckling. This species can easily be differentiated from Oxyrhopus petolarius by having a white-speckled, instead of completely black, snout. From D. gracilis, it differs by having a different interspace color pattern. In D. bobridgelyi, the pale interspaces are white with contrasting reddish-tan pigment in the center. In D. gracilis, they are completely light brown or light reddish white, gradually becoming reddish brown towards the center.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Dipsas bobridgelyi from Buenaventura Biological Reserve, El Oro province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Dipsas bobridgelyi is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed seasonally dry forests and foothill rainforests.1 These snakes appear to be more active during rainy or drizzly nights after a warm day.2 Their movements through the foliage are slow, graceful, and generally occur on the lower (1–2.5 m above the ground) forest stratum.1 The diet in this species consists of snails and probably also on slugs, which are presumably immobilized by the use of toxins secreted by the mucous cells of the infralabial glands.3 Nevertheless, all snakes in the genus Dipsas are considered harmless to humans. They never attempt to bite, resorting instead to coiling into a defensive ball posture and producing a musky and distasteful odor when threatened.2,4

Conservation: Endangered Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the near future.. Since it has only been recently described,1 Dipsas bobridgelyi has not been formally evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Here, it is provisionally assigned to the EN category following IUCN criteria5 because the species is restricted to only five patches of forest lacking connectivity between them and its habitat is severely fragmented and declining in extent and quality due to deforestation. It is estimated that, in total, there are no more than ~1,265 km2 of suitable habitat remaining for D. bobridgelyi. Furthermore, only two of the localities (Buenaventura Reserve in Ecuador and Reserva Nacional de Tumbes in Peru) where the species occurs are currently protected.1

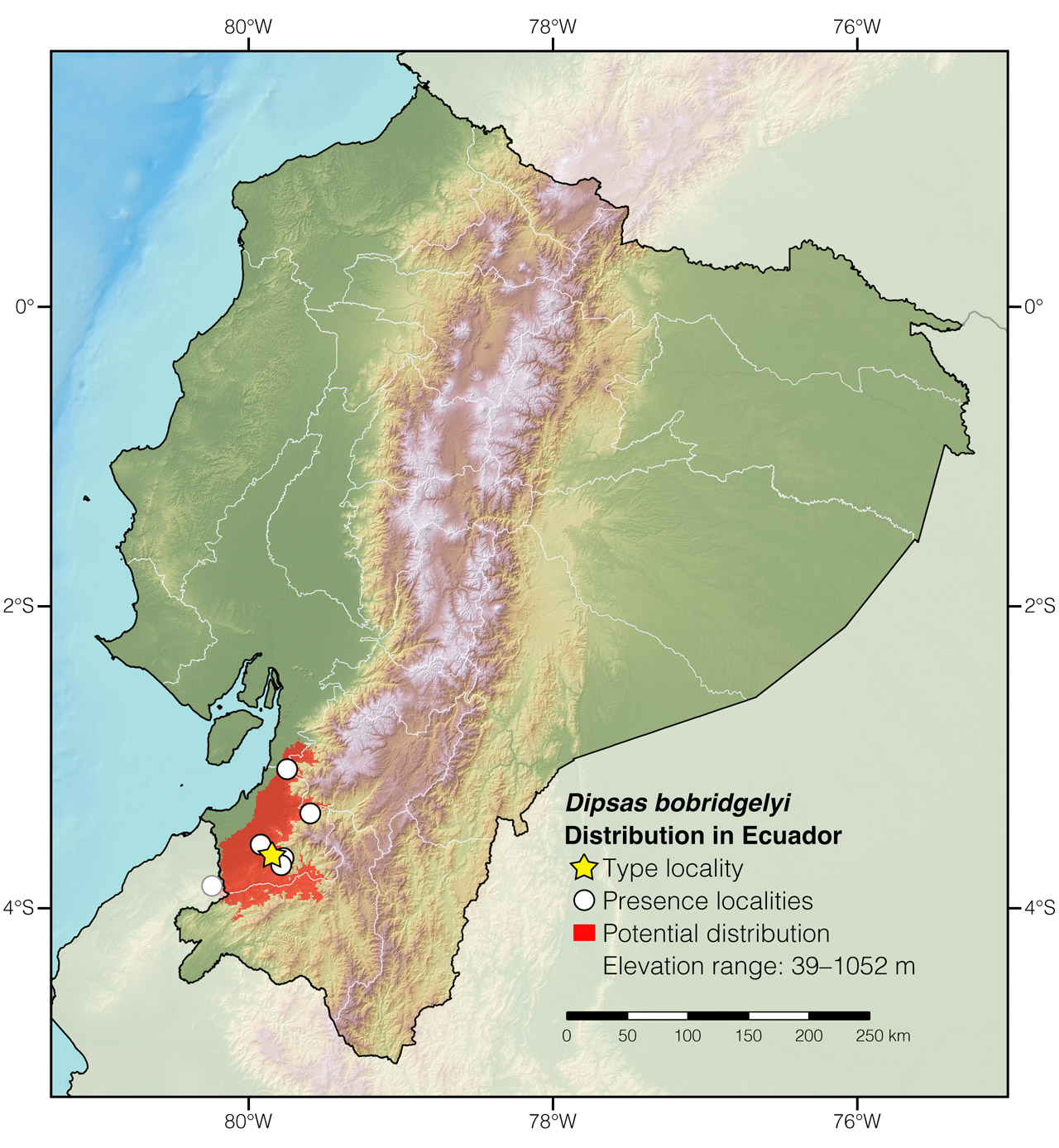

Distribution: Dipsas bobridgelyi is restricted to an area of approximately 5,321 km2 along the Chocoan-Tumbesian transition area of southwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2) and extreme northwestern Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Dipsas bobridgelyi in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Buenaventura Reserve, El Oro province, Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Dipsas comes from the Greek dipsa (=thirst) and probably refers to the fact that the bite of these snakes was believed to cause intense thirst.6 The specific epithet bobridgelyi honors Dr. Robert “Bob” S. Ridgely, a leading ornithologist and distinguished conservationist who has dedicated almost 50 years of his life to the study and conservation of birds and biodiversity across Latin America.1

See it in the wild: Bob Ridgely’s Snail-eating Snakes can be seen at a rate of about once every few nights, especially during the rainy season in western Ecuador (Dec–May). The only known location where this species can be seen reliably is Buenaventura Biological Reserve.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Bob Ridgely’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas bobridgelyi). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZFWJ6278

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Salazar-Valenzuela D, Mebert K, Peñafiel N, Aguiar G, Sánchez-Nivicela JC, Pyron RA, Colston TJ, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Venegas PJ, Guayasamin JM, Torres-Carvajal O (2018) Systematics of South American snail-eating snakes (Serpentes, Dipsadini), with the description of five new species from Ecuador and Peru. ZooKeys 766: 79–147. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.766.24523

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- De Oliveira L, Jared C, da Costa Prudente AL, Zaher H, Antoniazzi MM (2008) Oral glands in dipsadine “goo-eater” snakes: morphology and histochemistry of the infralabial glands in Atractus reticulatus, Dipsas indica, and Sibynomorphus mikanii. Toxicon 51: 898–913. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.12.021

- Cadle JE, Myers CW (2003) Systematics of snakes referred to Dipsas variegata in Panama and Western South America, with revalidation of two species and notes on defensive behaviors in the Dipsadini (Colubridae). American Museum Novitates 3409: 1–47.

- IUCN (2012) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. Second edition. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 32 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dipsas bobridgelyi in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Ponce Enríquez | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Buenaventura Biological Reserve* | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Ñalacapac | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Remolino | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Vía a Chilla | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Tumbes | Quebrada Los Naranjos | Cadle 2005 |