Published November 21, 2021. Updated December 2, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Hippie Anole (Anolis fraseri)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Anolidae | Anolis fraseri

English common names: Hippie Anole, Fraser’s Anole.

Spanish common names: Anolis hippie, anolis de Fraser.

Recognition: ♂♂ 40.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=10.9 cm. ♀♀ 40.1 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=11.6 cm..1,2 Anoles are easily distinguishable from other lizards by their diurnal habits, extensible dewlap in males, expanded digital pads, and granular scales on the dorsum and belly.3 The Hippie Anole (Anolis fraseri) is the largest anole in its area of distribution.1 It can be distinguished from other species of Anolis with which it co-occurs on the basis of its large size, fleshy crest behind the head, plain saffron dewlap, and unique coloration.1,4 The dorsum is greenish yellow with irregular darker bands. Males of A. fraseri differ from females by having a taller crest, larger dewlap, and a more vidid coloration that includes a reddish head.1,4 In Ecuador, A. fraseri is most similar to A. nemonteae, a species having a different dewlap coloration and restricted to southwestern Ecuador.5 Three other Chocoan anoles similar to A. fraseri are A. parilis, A. princeps, and A. purpurescens.5 However, these are all smaller in body size and have a brighter green coloration with little or no black bands and blotches.

Figure 1: Individuals of Anolis fraseri from Finca Elenita, Pichincha province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Anolis fraseri is a locally frequent lizard that is often overlooked due to its arboreal habits.6 The species inhabits old-growth or disturbed rainforests, cloud forests, and semi-open areas such as forest borders, roadside vegetation,7 plantations (particularly of guava and sunflowers), and rural gardens.6,8,9 During the daytime, individuals are usually active on twigs, branches, tree trunks, palm fronds, and leaves, but may as well be seen on rooftops,10 street power lines,11 or at ground level crossing trails and dirt roads.1,6,9 Although Hippie Anoles perch higher than other co-occurring anoles (up to ~13 m above the ground),6,9 and the species is included in the “crown giant” anole guild,8 this lizard is not restricted to the crown of large trees; it can also be found on small trees and shrubs 2–4.5 m above the ground.1,6 Anolis fraseri is a diurnal species, active during sunny periods when the ambient temperature is 18.8–29.8°C.9 At night, individuals sleep on twigs and branches 0.2–5 m above the ground with the head oriented towards the end of the branch.6 This behavior allows them to detect potential predators by sensing the vibration on the branch, to which they respond by jumping and disappearing into the dark.6 The diet of A. fraseri is based primarily on large (6.61 ± 2.67 mm long)9 active canopy insects, larger than those taken by other co-occurring anoles.1,9 Numerically, the most abundant prey items consumed in a sampled Ecuadorian population were insects in the order Hymenoptera (wasps, bees, and ants; 21.43%), followed by hemipterans, spiders, moths, grasshoppers, flies, ants, shed-skin, and seeds.9 Hippie Anoles can change their dorsal coloration when disturbed: going from bright yellowish green to dark brown.1,6 The cryptic coloration and twig-like motion is their primary defense mechanism, but individuals may perform a threat display and even bite when cornered.1,6 Nothing is known about the reproductive habits of this species, but its closest living relative lays clutches of a single egg.5 Males defend territories and court females using visual signals such as head bobs and dewlap displays.6

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Anolis fraseri is proposed to be listed in this category, instead of Least Concern,12,13 because the species is almost certainly much less widely-distributed that previously thought. Instead of being distributed from the northern Andes of Colombia to western Ecuador,4 in this work, the “true” A. fraseri is considered to be restricted to an area smaller than 20,000 km2 in western Ecuador. Moreover, ~55% of this area has already been converted to pastures and agricultural fields and each year it loses an additional 254 km2 of forest cover.14 Although it could qualify for threatened category, the species appears well adapted to human-modified environments. Additionally, nearly half of all localities (26 of 53; Appendix 1) where A. fraseri has been recorded are in privately protected areas, and anecdotal information6 suggests that populations in Pichincha, Cotopaxi, and Santo Domingo provinces are stable.

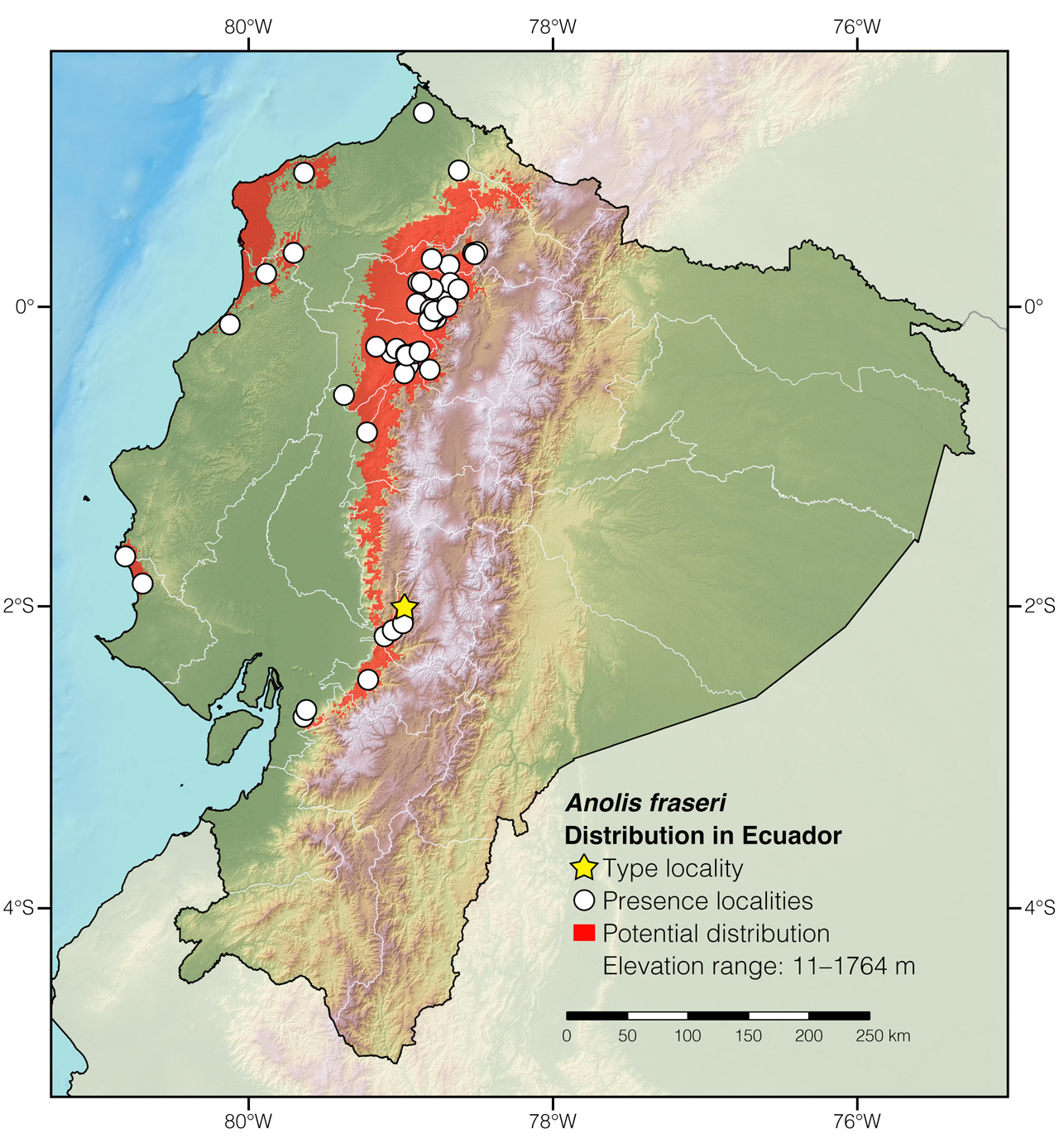

Distribution: Anolis fraseri is endemic to an estimated 17,759 km2 area on the Chocoan lowlands and adjacent Andean foothills of western Ecuador. The species has been recorded at elevations between 11 and 1764 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Anolis fraseri in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Pallatanga. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Anolis is thought to have originated from Cariban languages, specifically from the word anoli, which is the name Arawak peoples may have used to refer to this group of lizards.15 The specific epithet fraseri honors Louis Fraser, a British zoologist and naturalist who collected the specimen on which the original description of the species was based.

See it in the wild: Due to their arboreal habits, Hippie Anoles are usually overlooked by most visitors to the forests of western Ecuador. However, these anoles are common in some areas and easy to locate in a specific patch of trees where individuals have been spotted previously. The area with the greatest number of observations is Mindo, a valley and town in Pichincha province. In Mindo, Hippie Anoles are most often seen in rural gardens surrounded by lush vegetation and, especially, on guava trees and living fences near forest borders. The lizards are more easily located at night, as they will be roosting on small twigs where their bright whitish bellies stand out when lit with a flashlight.

Special thanks to Randal and Kalyn for symbolically adopting the Hippie Anole and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2023) Hippie Anole (Anolis fraseri). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/UMFF2758

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Williams EE, Rand H, Rand AS, O’Hara RJ (1995) A computer approach to the comparision and identification of species in difficult taxonomic groups. Breviora 502: 1–47.

- Peters JA, Donoso-Barros R (1970) Catalogue of the Neotropical Squamata: part II, lizards and amphisbaenians. Bulletin of the United States National Museum, Washington, D.C., 293 pp.

- Williams EE (1966) South American anoles: Anolis biporcatus and Anolis fraseri (Sauria, Iguanidae) compared. Breviora 239: 1–14.

- Ayala-Varela F, Valverde S, Poe S, Narváez AE, Yánez- Muñoz MH, Torres-Carvajal O (2021) A new giant anole (Squamata: Iguanidae: Dactyloinae) from southwestern Ecuador. Zootaxa 4991: 295–317. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4991.2.4

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Poe S, Ayala F, Latella IM, Kennedy TL, Christensen JA, Gray LN, Blea NJ, Armijo BM, Schaad EW (2012) Morphology, phylogeny, and behavior of Anolis proboscis. Breviora 530: 1–11.

- Miyata KI (2013) Studies on the ecology and population biology of little known Ecuadorian anoles. Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoology 161: 45–78.

- Boada Viteri EA (2015) Ecología de una comunidad de lagartijas del género Anolis (Iguanidae: Dactyloinae) de un bosque pie-montano del Ecuador occidental. BSc thesis, Quito, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 111 pp.

- Photo by Eric DeFonso.

- Photo by Ulises Balza.

- Castañeda MR, Castro F, Mayer GC (2020) Anolis fraseri. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T178282A18969846.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Allsopp R (1996) Dictionary of Caribbean English Usage. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 776 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Anolis fraseri in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Cañar | Hidroeléctrica Ocaña | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Hostería SantVal | This work |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | La Victoria | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Pallatanga* | Günther 1859 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Bosque Privado El Jardín de los Sueños | Photo by Christophe Pellet |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Damas | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Recinto Galápagos | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bilsa Biological Reserve | Ortega-Andrade et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Integral Otokiki | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Mateo | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Miguel de los Bancos | Photo by Andrés Portilla |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Bucay | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro de Hayas | This work |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Naranjal | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Apuela | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Cabañas Eco Junín | This work |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Cabañas Intag Colibrí | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Plaza Gutiérrez | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Reserva Los Cedros | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Centro Científico Río Palenque | Miyata 1976 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Hacienda Siberia | Hamilton et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama Coaque Reserve | Photo by Ryan Lynch |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Reserva Ayampe | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Dos Ríos, 4 km NE of | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Finca Elenita | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hacienda San Vicente | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Maquipucuna Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Garden Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo–El Cinto road | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo, 5 km E of | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegal | Williams 1966 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegalito, 2.5 km S of | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Near Finca Ecológica Orongo | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Quinta Santa Teresa de Pacto | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Las Tangaras | Photo by Marc Kramer |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Mashpi Amagusa | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Río Cinto | Photo by Lisa Brunetti |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | San Tadeo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Séptimo Paraíso Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi | Velasco & Hurtado-Gómez 2014 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandayapa Bird Lodge | Photo by Sam Woods |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Comuna Loma Alta | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Hacienda Tinalandia | Poe 2004 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | La Florida | MNHG 2463.043 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | La Unión del Toachi | Ayala-Varela et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Otongachi Reserve | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Río Faisanes | MHNG 2285.036 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Santo Domingo | Arteaga et al. 2013 |