Bev Ridgely's Snail-Eater |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Sibon | Sibon bevridgelyi

English common names: Bev Ridgely's Snail-Eater.

Spanish common names: Caracolera de Bev Ridgely.

Recognition: ♂♂ 84 cm ♀♀ 78.6 cm. In its area of distribution, The Bev Ridgely's Snail-Eater (Sibon bevridgelyi) is the only snake having the head much wider than the neck, bulging eyes, and a color pattern consisting of black-stippled irregular rusty to reddish brown blotches separated from each other by light pale yellow interspaces. The Cloudy Snail-Eater (S. nebulatus) has a similar body form, but the dorsum of this other speces is a combination of mainly black to dark-brown blotches or bands on a gray to grayish brown background (interblotch) color. The Mountain Snail-Eater (D. oreas) also occurs in alongside S. bevridgelyi in some localities, but it has a pattern of clearly defined (not irregular) elliptical dorsolateral blotches.

Picture: Adult from Cerro de Hayas, Guayas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Río Bucay, Bolívar, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male from Buenaventura Reserve, El Oro, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male from Palmales Nuevo, El Oro, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Locally frequent. Sibon bevridgelyi is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed deciduous forests, evergreen forests, shrublands, pastures, and cacao plantations, usually close to streams.1,2 Bev Ridgely's Snail-Eaters are active at night (20:56–03:56), especially if it is raining or drizzling.1 They move actively but slowly on vegetation 0.3–5 m above the ground.1 During the daytime, individuals sleep coiled under tree bark or in the center of palm trees up to 2 m above the ground.1 Their diet includes slugs and snails.1 Individuals of S. bevridgelyi are harmless to humans; they are extremely docile and never attempt to bite.2 If threatened, the snakes may produce a musky and distasteful odor.2

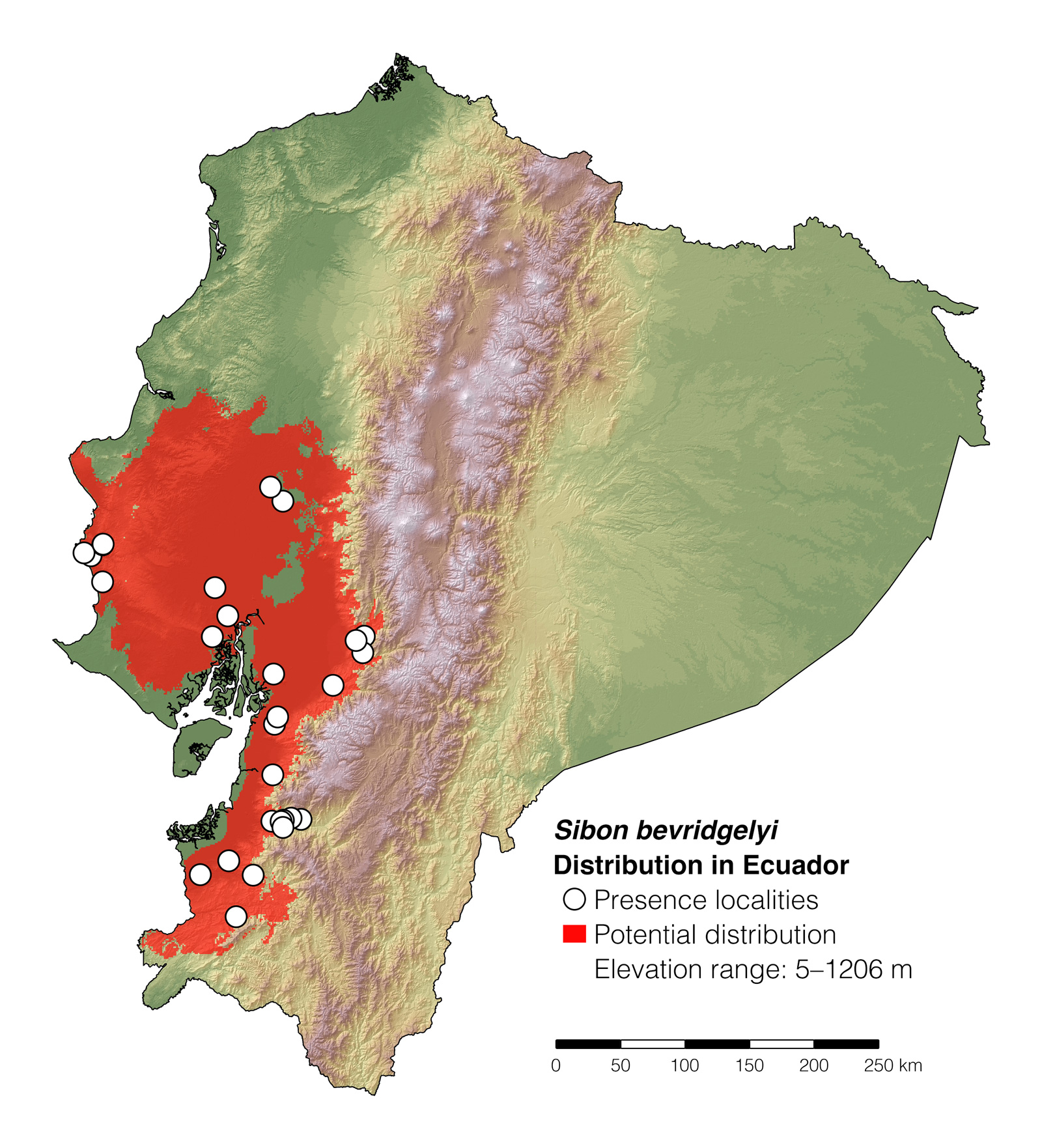

Conservation: Vulnerable.1 Sibon bevridgelyi is listed in this category following IUCN criteria3 because the species’ area of occupancy is estimated to be less than 20,000 km2 and is habitat is severely fragmented and declining in extent and quality due to deforestation.1 We estimate that only 26.2% (10,917 km2) of the potential distribution of S. bevridgelyi in Ecuador holds habitat where the species might persist. Furthermore, only three of the localities (Machalilla National Park, Buenaventura Reserve, and Ayampe Reserve) where S. bevridgelyi occurs are currently protected.1

Distribution: Sibon bevridgelyi is native to the Tumbesian lowlands and adjacent Andean foothills of southwestern Ecuador and northwestern Perú.

Etymology: The generic name Sibon is probably derived from the Latin word sibonis (a kind of “hunting spear”).4 It may refer to the shape of the head in this group of snakes. The specific epithet bevridgelyi honors the late Prof. Beverly S. Ridgely, life-long birder and conservationist, and father of Robert S. Ridgely, well known in Ecuadorian ornithological circles and co-author of The Birds of Ecuador. Though he never got to visit Buenaventura, from afar Bev continued to delight in the conservation successes of Fundación Jocotoco, which now owns and manages one of the few protected areas where the Vulnerable S. bevridgelyi is known to occur.1

See it in the wild: Bev Ridgely's Snail-Eaters can be seen with ~10–30% certainty at night, especially after a rainy day, in Buenaventura Reserve. The best way to detect the snakes is by scanning low vegetation along trails.

FAQ

Are snail-eating snakes venomous? No, but some species have glands in the lower jaw which produce a mucous secretion that presumably causes paralysis and death of the mollusks they consume. This secretion also facilitates prey lubrication during ingestion.5

Do snails attract snakes? Yes. Snail-eating snakes follow snails visually or by tracking their scent trail.6

Do snail-eating snakes eat the shell of the snails? They don't. These snakes use specialized muscular contractions of their wedge-like head to extract snails from their shells.6

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Frank PichardoaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Sibon bevridgelyi. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Salazar-Valenzuela D, Mebert K, Peñafiel N, Aguiar G, Sánchez-Nivicela JC, Pyron RA, Colston TJ, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Venegas PJ, Guayasamin JM, Torres-Carvajal O (2018) Systematics of South American snail-eating snakes (Serpentes, Dipsadini), with the description of five new species from Ecuador and Peru. ZooKeys 766: 79–147.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- Lee JC (1996) The amphibians and reptiles of the Yucatán Peninsula. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca, 500 pp.

- De Oliveira L, Jared C, da Costa Prudente AL, Zaher H, Antoniazzi MM (2008) Oral glands in dipsadine “goo-eater” snakes: morphology and histochemistry of the infralabial glands in Atractus reticulatus, Dipsas indica, and Sibynomorphus mikanii. Toxicon 51: 898–913.

- Sheehy C (2012) Phylogenetic relationships and feeding behavior of Neotropical snail-eating snakes (Dipsadinae, Dipsadini). PhD Thesis, UT Arlington.