Cloudy Snail-Eater |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Sibon | Sibon nebulatus

English common names: Cloudy Snail-Eater, Cloudy Snail-Sucker.

Spanish common names: Caracolera nublada, caracolera nebulosa.

Recognition: ♂♂ 83 cm ♀♀ 101.3 cm. In northwestern Ecuador, The Cloudy Snail-Eater (Sibon nebulatus) is the only snake having the head much wider than the neck, bulging eyes, and a dorsal color pattern consisting of black to dark-brown blotches or bands on a gray to grayish brown background (interblotch) color. The Ringed Snail-Eater (S. annulatus) has a similar body form, but it has an olive to green dorsum with reddish rings. In cloud forests of northwestern Ecuador, S. nebulatus is often confused with the Elegant Snail-Eater (Dipsas elegans), but this other snake has a pattern of vertical bars between which there is a more or less distinct narrow pale bar.

Picture: Adult from FCAT Reserve, Esmeraldas, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult from Masphi Lodge, Pichincha, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Common. Sibon nebulatus is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen lowland and foothill forests, rural gardens, and plantations, usually close to bodies of water.1–3 Cloudy Snail-Eaters are active at night, especially if it is raining or drizzling.1 They move actively but slowly at ground level or on vegetation up to 3 m above the ground.1,4 During the daytime, they sleep coiled inside bromeliads, in the axils of palm fronds, or under rotting trunks, piled logs, and surface debris.1,4,5 Cloudy Snail-Eaters feed mostly on slugs and snails,1,6 which they follow visually or by tracking their scent trail,7 but may also opportunistically consume frog eggs and earthworms.8,9 The snakes extract the snails from their shells by using a “snag and drag” behavior. They bite the snail, drag it until the shell is wedged against the substrate, and pull until the snail is extracted.7 Individuals of S. nebulatus are harmless to humans; they are extremely docile and never attempt to bite.1 If threatened, individuals may flatten their body, expand their head to simulate a triangular shape, and produce a musky and distasteful odor.10 Aggregations of seven females of S. nebulatus in the same tree, presumably related to feeding, have been reported.11 Sibon nebulatus breeds throughout the year.4 Females lay clutches of 3–9 eggs.4,11 These take 67–68 days to hatch.12

Conservation: Least Concern.13 Sibon nebulatus is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, frequently encountered in some parts of its range, and is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.13 In a rainforest locality in Panamá, the occurrence rates of S. nebulatus have remained constant in the period from 1997 to 2012.14 Despite being listed as Least Concern, the species faces the threat of habitat loss and traffic mortality.1,15

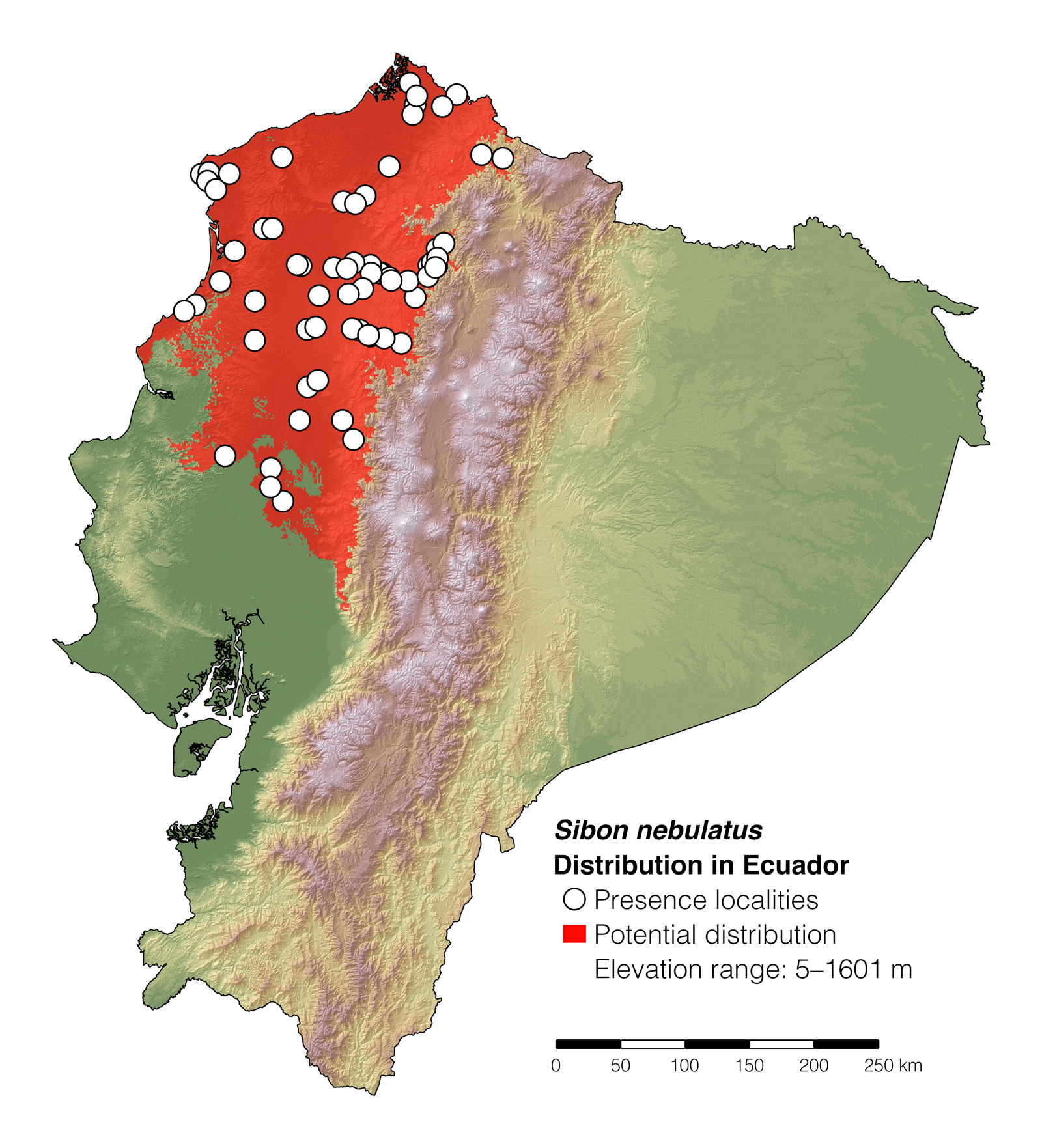

Distribution: Sibon nebulatus occurs throughout the Mesoamerican lowlands and adjacent mountain foothills from southern México to western Panamá, as well as along the Chocó and Río Magdalena valley regions from eastern Panamá, through Colombia, to northwestern Ecuador. The species also occurs in northern South America along the Llanos, Andean foothills, coastal cordilleras, and Guiana Shield in Colombia, Guyana, French Guiana, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, and Venezuela.

Etymology: The generic name Sibon is probably derived from the Latin word sibonis (a kind of “hunting spear”).16 It may refer to the shape of the head in this group of snakes. The specific epithet nebulatus comes from the Latin word nebula (meaning “mist”) and the suffix -atus (meaning “provided with”).17 It most likely refers to the distinctive “cloudy” color pattern of this snake species.

See it in the wild: Cloudy Snail-Eaters can be seen with ~10–40% certainty at night, especially during the rainy season in western Ecuador (December to May), in forested areas throughout the specie's area of distribution. Some of the best localities to find Cloudy Snail-Eaters in Ecuador are: Bilsa Biological Reserve, El Jardín de los Sueños, and Mashpi Rainforest Reserve.

Special thanks to Johannes Penner for symbolically adopting the Cloudy Snail-Eater and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Frank PichardoaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Sibon nebulatus. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Lewis TR, Griffin RK, Grant PBC, Figueroa A, Ray JM, Graham KE, David G (2013) Morphology and ecology of Sibon snakes (Squamata: Dipsadidae) from two Neotropical forests in Mesoamerica. Phyllomedusa 12: 47–55.

- Lynch JD (2015) The role of plantations of the African palm (Elaeis guineensis Jacq.) in the conservation of snakes in Colombia. Caldasia 37: 169–182.

- Heimes P (2016) Snakes of Mexico. Chimaira, Frankfurt, 572 pp.

- Galvis-Peñuela PA, Mejía-Tobón A, Rueda-Almonacid JV (2011) Fauna silvestre de la Reserva Forestal Protectora Montes de Oca, La Guajira, Colombia. Corpoguajira, Bogotá, 822 pp.

- Ray JM, Montgomery CE, Mahon HK, Savitzky AH, Lips KR (2012) Goo-eaters: diets of the Neotropical snakes Dipsas and Sibon in Central Panama. Copeia 2012: 197–202.

- Sheehy C (2012) Phylogenetic relationships and feeding behavior of Neotropical snail-eating snakes (Dipsadinae, Dipsadini). PhD Thesis, UT Arlington.

- Ryan MJ, Lips KR (2004) Sibon argus (NCN) diet. Herpetological Review 35: 278.

- Field notes of Jorge Zuñiga.

- Cadle JE, Myers CW (2003) Systematics of snakes referred to Dipsas variegata in Panama and Western South America, with revalidation of two species and notes on defensive behaviors in the Dipsadini (Colubridae). American Museum Novitates 3409: 1–47.

- Campbell JA (1998) Amphibians and reptiles of northern Guatemala, the Yucatán, and Belize. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 380 pp.

- Solórzano A (2004) Serpientes de Costa Rica. Distribución, taxonomía e historia natural. Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, 792 pp.

- Flores-Villela O, Porras LW, Solórzano A, Sunyer J, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Rivas G, Renjifo J, Caicedo J, Nogueira C, Murphy J (2019) Sibon nebulatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Zipkin EF, DiRenzo GD, Ray JM, Rossman S, Lips KR (2020) Tropical snake diversity collapses after widespread amphibian loss. Science 367: 814–816.

- Vargas-Salinas F, Delgado-Ospina I, López-Aranda F (2011) Mortalidad por atropello vehicular y distribución de anfibios y reptiles en un bosque subandino en el occidente de Colombia. Caldasia 33: 121–138.

- Lee JC (1996) The amphibians and reptiles of the Yucatán Peninsula. Comstock Publishing Associates, Ithaca, 500 pp.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.