Published October 31, 2021. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Black-necked Coralsnake (Micrurus obscurus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Elapidae | Micrurus | Micrurus obscurus

English common names: Black-necked Coralsnake, Amazon Coralsnake, Amazonian Coralsnake.

Spanish common names: Coral cuello negro, coral amazónica cuello negro.

Recognition: ♂♂ 139.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 155.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=148 cm..1,2 In Ecuador, the majority of true coral snakes (genus Micrurus) can be distinguished from most, but not all, false coralsnakes by having brightly colored rings that encircle the body (rings evident on the belly), small eyes that are about the same size as the post-ocular scales, and no loreal scale.1,3 In the Amazon rainforest of Ecuador, the Black-necked Coralsnake (M. obscurus) is one of four species in the genus having black rings arranged in triads, rather than in monads.1 The other three snakes are M. helleri, M. ortoni, and M. surinamensis. Micrurus obscurus differs from all of them by having a cream snout with blackish blotches on each scale and by having cream-colored rings as wide (5–6 scales wide) as the adjacent black rings, instead of much narrower.4–6 The presence of complete black triads separates this species from the Aesculapian False-Coralsnake (Erythrolamprus aesculapii), a species that, in Ecuador, has black rings arranged in dyads.7

Figure 1: Adult female individual of Micrurus obscurus from Narupayacu, Napo province, Ecuador.

Natural history: UncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months.. Micrurus obscurus is a terrestrial to semi-fossorial (living underground and at ground level) snake that inhabits pristine to heavily disturbed rainforests, which may be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.1,2,8 This species also occurs in agricultural areas, clearings, rural gardens, and houses near forest borders.1,9,10 Individuals have been seen active on soil, leaf-litter, or crossing forest trails or roads during the day or at night.1,4,9,11 They also have been found hidden under logs or in nests of leaf-cutter ants.3,8 These snakes actively forage in search of prey, which includes snakes (Atractus collaris,8 Erythrolamprus chrisostomus,8 E. pygmaeus,8 E. reginae,5 Leptodeira annulata,1 Micrurus anellatus,5 Amerotyphlops reticulatus,1 Bothrops atrox,3 as well as unidentified species in the genera Atractus1 and Dipsas5), amphisbaenians (Amphisbaena bassleri),12 lizards (Arthrosaura reticulata,1 Kentropyx pelviceps8), and caecilians.5,13

Black-necked Coralsnakes rely on their warning coloration as a primary defense mechanism. Individuals are usually calm and try to flee when threatened. If disturbed, they engage in complex and seemingly erratic behavior: they hide the head beneath body coils, crawl spasmodically forward and then backward, flatten their body dorso-ventrally, and display their bright tails as a decoy.1,9 They are also capable of striking if provoked. There are records of centipedes preying upon individuals of Micrurus obscurus.14 Black-necked Coralsnakes are proteroglyphous (having fixed enlarged teeth towards the front of the maxilla) and venomous. The venom is less lethal (LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 0.8–4.25 mg/kg)12,15 than that of other Amazonian coralsnakes and the yield per bite is low (10–30.5 mg or 0.01–0.03 cc).12 The venom is mostly neurotoxic, but also has hemorrhagic, proteolytic, and myotoxic (muscle breaking) activities.16,17 In humans, it causes persistent excruciating pain,18 but no fatalities have been reported. In Ecuador, a female laid a clutch of seven eggs.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..19 Micrurus obscurus is included in this category because the species is widely distributed, occurs in major protected areas, has presumed stable populations, and is currently facing no major widespread extinction threats.19 The most important threat to the long-term survival of some populations is habitat destruction mostly due to mining, oil extraction, and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Individuals of M. obscurus also suffer from traffic mortality and direct killing at the hands of local people.2,9

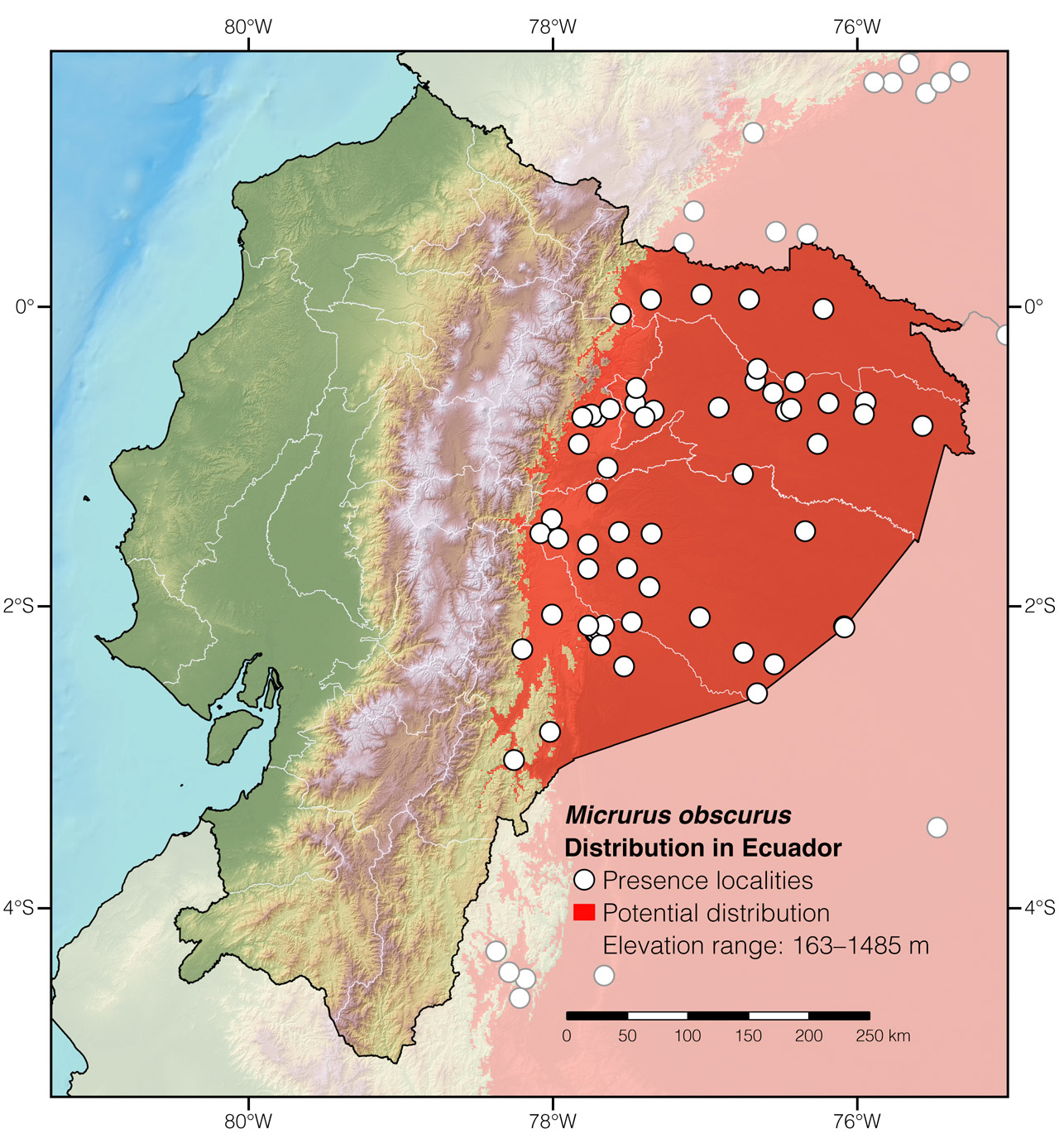

Distribution: Micrurus obscurus is native to the western Amazon basin and the adjacent foothills of the Andes in Brazil, Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.6 In Ecuador, the species has been recorded at elevations between 163 and 1485 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Micrurus obscurus in Ecuador. The type locality is Iquitos, Peru. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Micrurus, which is derived from the Greek words mikros (meaning “small”) and oura (meaning “tail”), refers to the short tail in members of this genus.3 The species epithet obscurus is a Latin word meaning “dark” or “obscured.” It probably refers to the dark pigment on the head scales of this snake species.5

See it in the wild: Black-necked Coralsnakes are usually found no more than once every few weeks at any given locality. In Ecuador, the areas having the greatest number of recent observations are Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary and the immediate environs of the town of Puyo. It appears that the best way to find Black-necked Coralsnakes is to walk along forest trails right after sunset, especially after a warm and rainy day.

Acknowledgments: This account was published with the support of Secretaría Nacional de Educación Superior Ciencia y Tecnología (programa INEDITA; project: Respuestas a la crisis de biodiversidad: la descripción de especies como herramienta de conservación; No 00110378), Programa de las Naciones Unidas (PNUD), and Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ).

Author and photographer: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2021) Black-necked Coralsnake (Micrurus obscurus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ESLN1031

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Melo-Sampaio PR, Lima Maciel JM, Braga de Oliveira CM, Da Silva Moura R, Bezerra de Lima LC (2013) Micrurus obscurus (Black-necked Amazonian Coralsnake): maximum size. Herpetological Review 44: 155.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Roze JA (1996) Coral snakes of the Americas: biology, indentification, and venoms. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, 328 pp.

- Nascimento LRS, Silva Jr NJ, Feitosa DT, Prudente ALC (2019) Taxonomy of the Micrurus spixii species complex (Serpentes, Elapidae). Zootaxa 4668: 370–392. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4668.3.4

- Curcio FF, Scali S, Rodrigues MT (2015) Taxonomic status of Erythrolamprus bizona Jan (1863 (Serpentes, Xenodontinae): assembling a puzzle with many missing pieces. Herpetological Monographs 29: 40–64. DOI: 10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-15-00002

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photo by Robinson Gutiérrez.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Silva Haad JJ (1994) Los Micrurus de la Amazonia Colombiana. Biología y toxicología experimental de sus venenos. Colombia Amazónica 7: 1–76.

- Greene HW (1976) Scale overlap as a directional sign stimulus for prey ingestion by ophiophagous snakes. Zeitschrift fur Tierpsychologie 41: 113–120. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1976.tb00473.x

- von May R, Biggi E, Cárdenas H, Diaz I, Alarcón C, Herrera V, Santa-Cruz R, Tomasinelli F, Westeen EP, Sánchez-Paredes CM, Larson JG, Title PO, Grundler MR, Grundler MC, Davis Rabosky AR, Rabosky DL (2019) Ecological interactions between arthropods and small vertebrates in a lowland Amazon rainforest. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 13: 65–77.

- da Silva Jr NJ, Aird SD (2001) Prey specificity, comparative lethality and compositional differences of coral snake venoms. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part C 128: 425–456. DOI: 10.1016/s1532-0456(00)00215-5

- Remuzgo C, Álvarez MP, Rodríguez E, Lazo F, Yarlequé A (2002) Micrurus spixi (Peruvian Coral Snake), venom, preliminary biochemical and enzymatic characterization. Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins 8: 161–167. DOI: 10.1590/S0104-79302002000100012

- Gutiérrez JM, Rojas G, da Silva Jr NJ, Núñez J (1992) Experimental myonecrosis induced by the venoms of South American Micrurus (coral snakes). Toxicon 30: 1299–1302. DOI: 10.1016/0041-0101(92)90446-c

- Warrell DA (2004) Snakebites in Central and South America: epidemiology, clinical features, and clinical management. In: Campbell JA, Lamar WW (Eds) The Venomous reptiles of the Western Hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 709–761.

- Hladki AI, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N, Gonzales L, Gagliardi G, Valencia J, Schargel W, Rivas G (2019) Micrurus obscurus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T44581983A44581992.en

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Micrurus obscurus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | El Paraíso | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | El Paujil | iNaturalist |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Granja Los Balcanes | Ayerbe et al. 2007 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Morelia | Photo by Yosthin Xelaya |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Reserva Natural y Ecoturistica Las Dalias | UAM-R-0407 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Río Pescado | ICN 051442 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Centro Experimental Amazónico | Betancourth-Cundar & Gutiérrez-Zamora 2010 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mocoa | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Asís | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Boy | Schmidt 1955 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Caucayá | ICN 051463 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | Schmidt 1953 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Santa Rosa de los Cofanes | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Amazonas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Boca del Río Zamora | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chiguaza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Napimias | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Normandía | AMNH |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Paantim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Samikim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tumpaim | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Wisui | Chaparro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | La Delicia | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Narupayacu | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pachakutik | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Y de Narupa | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Ávila Viejo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Chiru Isla, 4 km S of | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dayuma | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Hacienda Primavera | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | USNM 232483 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo NPF | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | Photo by Thierry García |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Huataraco | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Tiputini | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur-Iro, km 22 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur-Iro, km 96 | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Andoas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | USNM 232493 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cobaya Cocha | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Copataza (Achuar) | Peñafiel 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo, 10 km N of | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Copataza | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pindo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Pingullo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Tigre | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shiripuno Lodge | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tambo Unión | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano | USNM 232492 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yáñez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | MHNG 2399.001 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | UIMNH 54670 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Reserva de Producción Faunística Cuyabeno | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Galilea | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Paagat | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Cenepa | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Shaim | Nascimento et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Teniente Pinglo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pavayacu | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |