Published May 3, 2024. Updated October 25, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Hammer Watersnake (Hydrops martii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Hydrops martii

English common names: Hammer Watersnake, Coral Mud Snake.

Spanish common name: Culebra acuática martillo.

Recognition: ♂♂ 54.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=42.2 cm. ♀♀ 121.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=103.5 cm..1,2 Hydrops martii can be identified by having dorsally oriented eyes and nostrils, round pupils, a single internasal scale, no loreal scale, and smooth dorsal scales arranged in 17 rows at mid-body. The dorsal coloration itself is enough to identify this species from all other Amazonian snakes. It consists of 36–63 black transverse bands with white spots on the edges, separated from each other by olive interspaces enclosing brick red bands (Fig. 1).3 The head is grayish or beige and the snout is black with an irregular white band across the nostrils.3 The belly is yellowish white with full black bands or with the bands interspersed in a checkered pattern. This species differs from H. triangularis by lacking a complete pale ring around the neck as well as by having dorsal scales arranged in 17, instead of 15, rows at mid-body.3–5 From snakes of the genus Helicops, it differs by having smooth, instead of keeled, dorsal scales. From Micrurus surinamensis, it differs by having black rings not arranged in triads.4

Figure 1: Individuals of Hydrops martii from Tucan Lodge, Cuyabeno Reserve, Sucumbíos province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Hydrops martii is an aquatic snake that inhabits rivers, streams, wetlands, and lagoons in lowland rainforests with various degrees of human intervention.3,6 Hammer Watersnakes can be seen foraging during the day between 4 and 9 pm or at night and typically in water or on mud along the bank.3,6,7 When not active, individuals hide in small areas of built up leaf litter under the water.7 Their diet consists of fish of the orders Gymnotiformes, Siluriformes, and Synbranchiformes.6–11 There are recorded instances of piranhas (Serrasalmus rhombeus) and anacondas (Eunectes murinus) preying upon individuals of this species.7,12 When captured, the Hammer Watersnake thrashes the body, bites, produces cloacal discharges, and can regurgitate prey.6 The clutch size in this species consists of 7–23 eggs laid during the local low-water season.10,11,13

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..14 Hydrops martii is listed in this category primarily because the species has a wide distribution spanning many protected areas. Although there is no information on the population trend of the Hammer Watersnake, its numbers are expected to be declining alongside the decrease in water quality throughout the Amazonian river systems.

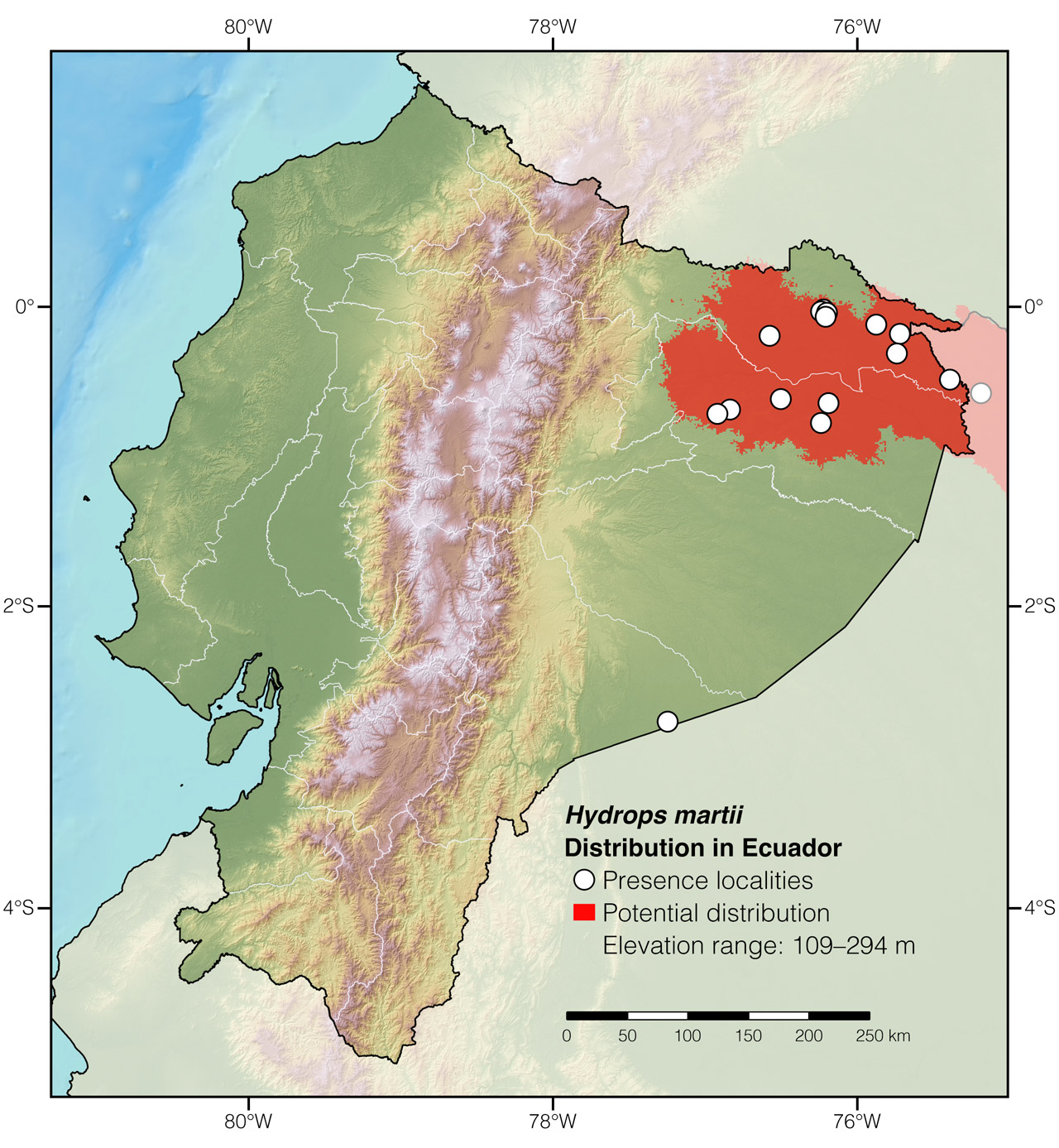

Distribution: Hydrops martii is widely distributed throughout the Amazon lowlands of Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Guyana, Perú, and Venezuela.11

Figure 2: Distribution of Hydrops martii in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Hydrops comes from the Greek words hydor (=water) and ops (=eye),15 and refers to the dorsally positioned eyes adapted to the aquatic lifestyle. The specific epithet martii honors Carl Friedrich Phillip von Martius, a German botanist, who together with Johann Baptist von Spix, collected the holotype of this species in the Bavarian Expedition to Brazil.16

See it in the wild: Hydrops martii can be located at a rate of about once every few months in forested areas throughout the species’ area of distribution in Ecuador, especially along the slow-moving blackwater rivers of Cuyabeno Reserve. These snakes are most easily detected by scanning the shallow water along large rivers and lagoons at night.

Special thanks to Jill Hanna for symbolically adopting the Hammer Watersnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Harry Turner for finding the specimens of Hydrops martii photographed in this account.

Authors: Juan Acosta-Ortiz,aAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia. Alejandro González-Rojas,aAffiliation: Universidad de los Llanos. Villavicencio, Colombia. Andrés F. Aponte-Gutiérrez,bAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.,cAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagadAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Acosta-Ortiz J, González-Rojas A, Aponte-Gutiérrez A, Arteaga A (2024) Hammer Watersnake (Hydrops martii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/HKMJ3944

Literature cited:

- Hoogmoed M, Gruber U (1983) Spix and Wagler type specimens of reptiles and amphibians in the Natural History Musea in Munich (Germany) and Leiden (The Netherlands). Spixiana 9: 319–415.

- Albuquerque NF (2000) The status of Hydrops martii (Wagler 1824) (Serpentes: Colubridae). Boletim Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi 16: 153–162.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- de Fraga R, Lima AP, da Costa Prudente AL, Magnusson WE (2013) Guia de cobras da região de Manaus - Amazônia Central. Editopa Inpa, Manaus, 303 pp.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Harry Turner, pers. comm.

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, da Costa Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Cunha OR, do Nascimento FP (1994) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 9: 1–191.

- Albuquerque N, Camargo M (2004) Hábitos alimentares e comentários sobre a predação e reprodução das espécies do gênero Hydrops Wagler, 1830 (Serpentes: Colubridae). Comunicações do Museu de Ciências e Tecnologia da PUCRS, Série-Zoologia 17: 21–32.

- Scartozzoni R (2009) Estratégias reprodutivas e ecologia alimentar de serpentes aquáticas da tribo Hydropsini (Dipsadidae, Xenodontinae). PhD thesis, Universidad de São Paulo, 160 pp.

- Tavares-Pinheiro R, Esteves-Silva PH, Brito Oliveira MS, de Figueiredo VAMB, Tavares-Dias M, Costa-Campos CE (2020) Predation on the Amazon Water Snake Hydrops martii (Squamata: Dipsadidae) by the Redeye Piranha Serrasalmus rhombeus (Serrasalmidae). Herpetology Notes 13: 553–554.

- Braz H, Scartozzoni R, Almeida-Santos SM (2016) Reproductive modes of the South American water snakes : a study system for the evolution of viviparity in squamate reptiles. Zoologischer Anzeiger 263: 33–44. DOI: 10.1016/j.jcz.2016.04.003

- Ortega A, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Calderón M, Nogueira CC, Gagliardi G, Schargel W, Rivas G (2019) Hydrops martii. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T176818A44950341.en

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011) The eponym dictionary of reptiles. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 296 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Hydrops martii in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Amazonas | La Pedrera | MZB 2003-1979 |

| Colombia | Amazonas | Leticia, 15 km N of | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mashumarentsa | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Guiyero | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pindo | Photo by Ernesto Arbeláez |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Auca | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Zaparo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Campamento Güeppi | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Zábalo, 6 km NW of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Cuyabeno, Río Güeppi | Cisneros-Heredia 2005 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Laguna Grande | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Otorongo Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Plataforma Espejo 1 | Consultora Cinge 2012 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente Cuyabeno, 11 km E of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tapir lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tucan Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Perú | Loreto | Centro Union | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Challavitas | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Iquitos | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Mazán | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Nanay | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Pebas | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Redondococha | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Cuchabatay | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Itaya | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Ucayali | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Loreto | Yanashi | Nogueira et al. 2019 |