Hawksbill |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Cheloniidae | Eretmochelys imbricata

English common names: Hawksbill, Hawksbill Sea Turtle.

Spanish common name: Carey, tortuga carey.

Recognition: ♂♂ 85 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 114 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace.. Members of Eretmochelys imbricata can be separated from other sea turtles by having four pairs of costal shields, two pairs of prefrontals, and overlapping carapace shields. They can also be recognized by their elongated head that ends in a sharp, curvy beak, and their serrated carapace margins, which resemble a saw. Adult males and females are similar in size, but males have a long thick tail and a slightly concave plastron (the ventral part of the shell).

Picture: Adult female. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Post-hatchling. Parque Nacional Machalilla. Manabí, Ecuador. | |

| |

Natural history: Uncommon. After hatching on tropical beaches, hatchlings of Eretmochelys imbricata frantically swim for 1–3 days in an offshore direction until they reach open ocean "nursery" habitats1,2 where they spend 7–10 years2 drifting in masses of floating seaweed along with surface currents. Some hatchlings remain on coastal pelagic waters or reefs close to their natal beaches.1 During this early stage, Hawksbills are diurnal predators of fish and their eggs, tunicates, crabs, barnacles, beetles, algae, and woody plant remains.1,3 At night, they spend most of their time floating at the surface.4 Hawksbill Sea Turtle hatchlings worldwide are preyed upon by a variety of animals, including skunks, raccoons, sea birds, kites, owls, crows, sharks, fish, and crabs.5–7

Special thanks to Jeanne O'Connell and Tudor Selescu, our two official protectors of the Hawksbill Sea Turtle, for symbolically adopting this species and helping bring the Reptiles of Galápagos project to life.

When they reach a carapace length of 13–35 cm,3,4 Hawksbill Sea Turtles establish their home ranges in insular coral reefs, but also on rocky outcrops, banks, lagoons, and mangrove estuaries adjacent to their nesting areas.8,9 From this age onwards, the young Eretmochelys imbricata become diurnal carnivorous bottom feeders,3 actively foraging among coral crevices in search for sea sponges (which account for 90–95% of their diet),3 but also echinoderms (sea cucumbers and sea urchins), bryozoans, cnidarians (hydrozoans, hard coral, zoanthids, anemones, corallimorphs, jellyfish, and comb jellies), mollusks (squid, snails, nudibranchs, bivalves, and tusk shells), arthropods (crabs, lobsters, barnacles, and copepods), tunicates, fish, algae, sea grass, mangrove fruits and seeds, bark, and wood.3,4,7,8,10 Presumably as a result of this diet, individuals of E. imbricata are biofluorescent, although part of the fluorescence is likely emitted by algae living on the turtles.11

Hawksbill Sea Turtles spend up to 92% of the day12 conducting shallow (2–20 m deep) dives,12,13 although they can dive down to 200 m in depth14 and for up to 140 minutes.15 Occasionally, adults bask on shore during daytime.16 At night, they may also be active,2 but are generally sleeping under or wedged into coral or rock ledges8 in shallow (7–18 deep) water,12 surfacing for air every 35–45 minutes.17 Adults of Eretmochelys imbricata tend to be permanent residents of 75–1,070 km2 foraging home ranges14 in coastal waters within 1 km from shore.1 However, some individuals migrate. They travel (probably using geomagnetic cues)18 across open ocean to distant (up to 4,669 km away)19 rookeries, foraging grounds, or nesting beaches.

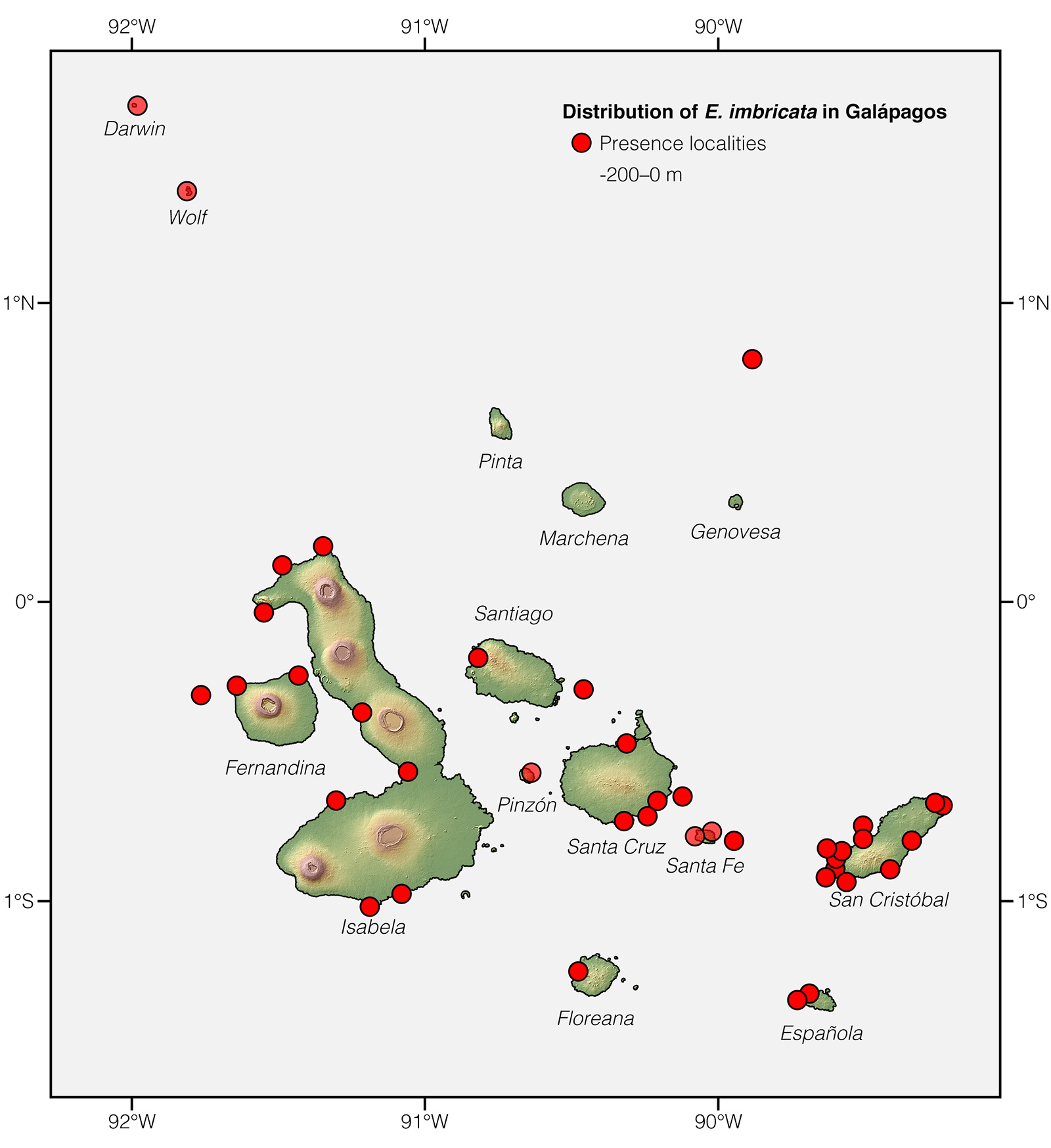

In the Galápagos Archipelago, some Hawksbill Sea Turtles reside and breed in the islands, but others migrate to nesting grounds in Central and South America.20,21 On the coast of mainland Ecuador, some breed and feed locally,9,22,23 but others also travel to Galápagos and presumably elsewhere along the eastern Pacific.21

Hawksbills become sexually mature at an age of 31–38 years.6 From this age onwards, they gather in polyandrous (a female copulates with more than one male)8 breeding rookeries in shallow waters not necessarily close to the nesting beaches.6 Here, copulation takes place on the water surface and may last for 1–3 hours.24 Hybridization between individuals of E. imbricata and other sea turtle species such as Caretta caretta,25 Chelonia mydas,26 and Lepidochelys olivacea,27 occurs. Female Hawksbill Sea Turtles are capable of storing sperm throughout the breeding season,28 and in some populations 6–100% of the resulting clutches are sired by multiple males.28–30

Hawksbill Sea Turtles nest every 2–9 years6 on roughly (less than 3.2 km apart)4 the same beaches (which may also be the same on which they themselves hatched),30 but may sometimes select different beaches up to 38 km apart.2 In Ecuador, females nest between November and April.31,32 During a single season, females of Eretmochelys imbricata may lay 1–7 clutches6 at intervals of 8–30 days.4,6 They produce 21–257 eggs per clutch6,33 and lay them on small isolated beaches8 in 17–72 cm deep nests,6 usually in the sand under vegetation34 at night.8 During nesting emergences, which last 1–2.5 hours,8 the females are very shy, and can easily be scared back into the sea.35 Nesting is mostly solitary,8 with usually no more than 94 females nesting in a single beach per season.36

The incubation period for Hawksbill eggs is 43–91 days,8 and an average of 37–100% of the eggs hatch.6 Temperature determines the sex of the offspring,37 and the proportion of female hatchlings increases with the incubation temperature.2 In nesting grounds throughout the world, eggs of Eretmochelys imbricata are preyed upon mostly by mammals (including pigs, foxes, dogs, skunks, mongooses, raccoons, coatis, genets, and rats), but also by monitor lizards, crabs, ants, and fly larvae.2,7,8 They are also occasionally lost to storms, high tides, sand displacement, and disturbance by other nesting turtles, in addition to being widely used for human consumption.6,8,38 The eggs hatch synchronously and usually at night or late in the afternoon,8 but some hatchlings are unable to dig their way out of the nest, and perish.8 During nocturnal emergence, the presence of artificial lighting affects the orientation of hatchlings,8 which may result in mortality caused by traffic. During diurnal emergence, desiccation causes hatchling mortality.8 From the surviving stock, it is estimated that less than 0.1% reach maturity.39

In addition to predation by sharks,40 large fish,41 crocodiles,42 and jaguars,43 causes of mortality for adult Hawksbills include hurricanes,24 ingestion of plastic,44 collision with boats,24 interactions with fishing gear,8 direct harvesting for meat consumption (although their meat may cause food poisoning),8 and oil spills.45 Individuals of Eretmochelys imbricata are parasitized by a variety of worms,46 leeches,47 and colonized by crustaceans (including amphipods, crabs, and barnacles), polychaetes, nudibranchs, ascideans, ophiuroids, blue-green bacteria, and algae.6,8 The maximum estimated lifespan of members of E. imbricata is 55 years.2

Conservation: Critically Endangered.48 Eretmochelys imbricata is listed in this category because its populations have declined 84–87% over the past three generations as a result of over-exploitation of adults to provide for the "tortoise shell" industry, direct harvesting of eggs and adults for meat, incidental mortality due to interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.48 Another threat faced by E. imbricata is climate change. Since temperature during incubation determines the sex of the offspring,37 the increase of the average global temperature may result in the complete feminization of some populations.49 Similarly, deforestation in nesting areas also produces a temperature increase that results in a sex ration distortion, where the proportion of females is much higher than males.50 Under some scenarios of global sea level rise, up to 50–51% of nesting beach area for E. imbricata may be lost by 2100.51,52

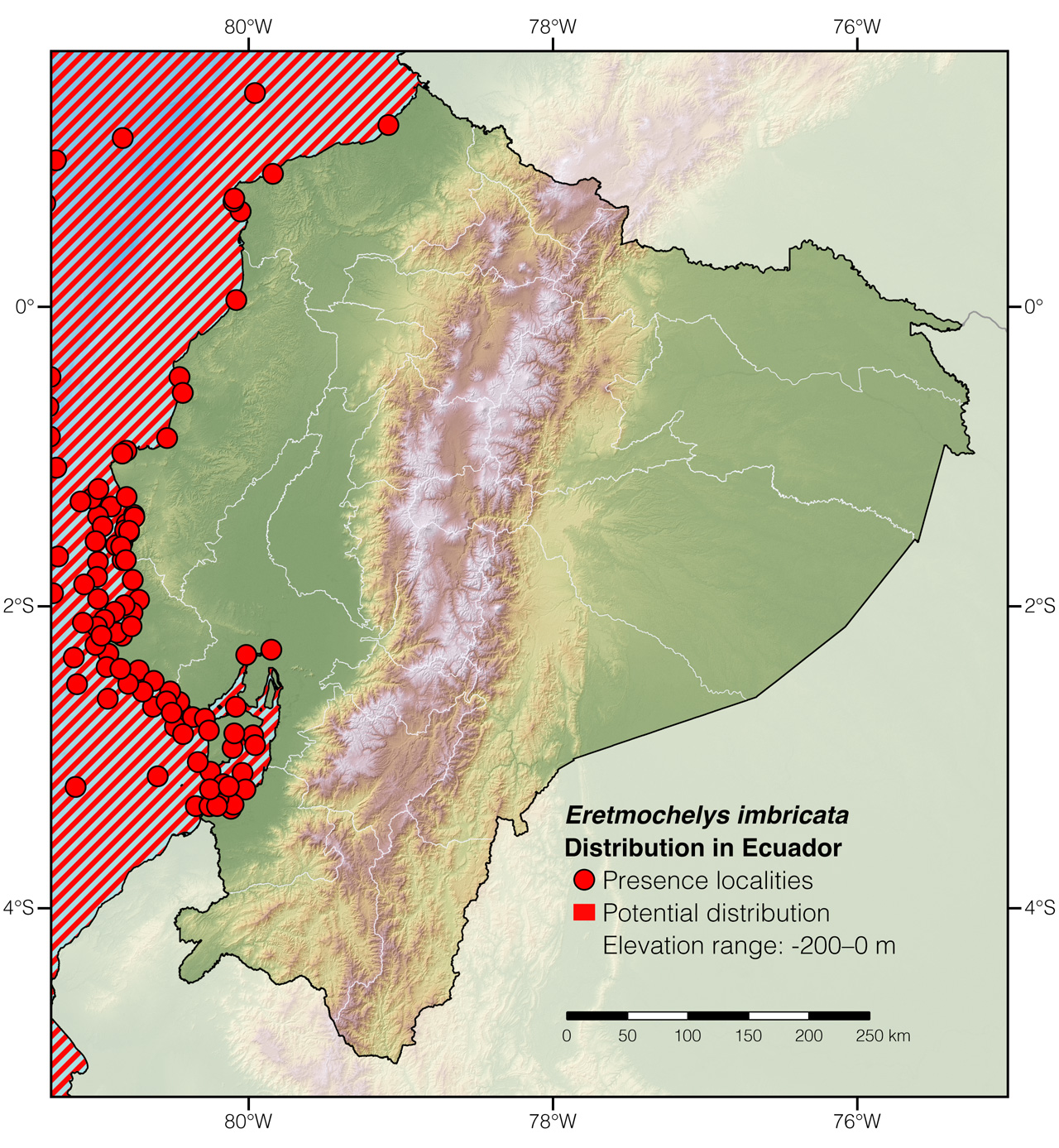

Distribution: The entire tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans.

Etymology: The generic name Eretmochelys, which comes from the Greek words eretmon (meaning “oar”) and chelys (meaning “turtle”),53 is probably a reference to the paddle-shaped limbs. The specific epithet imbricata, which comes from the Latin word imbricatus (meaning “overlapping”),53 refers to the overlapping carapace shields.

See it in the wild: Individuals of Eretmochelys imbricata can be seen year-round with ~10% certainty in shallow waters throughout Galápagos, especially near Puerto Baquerizo Moreno. Swimming Hawksbills can occasionally be observed from boats going to and from tourism sites, but they are easier to spot while snorkeling or diving in coral reefs. Along the coast of mainland Ecuador, E. imbricata is harder to see. Although the species nests roughly on the same beaches during the same months, witnessing such events is rare. Swimming Hawksbills can occasionally be observed while navigating on motorized boats off the coast of Machalilla National Park.

FAQ

Do Hawksbill Turtles live in groups? They do not. They are solitary. Even during an entire nesting season (which lasts several months), usually no more than 94 females may arrive to nest at the same beach.36

How big are Hawksbill Turtles? Hawksbill Turtles can grow up to 114 cm in straight carapace length (slightly over a meter or ~3.74 feet).

How long can a Hawksbill Turtle stay underwater? The maximum recorded duration of a Hawksbill's voluntary dive is 140 minutes (slightly over two hours).15

What does the Hawksbill Turtle do? Adult Hawksbill Sea Turtles spend up to 92% of the day12 diving less than 20 m from the surface,12,13 mostly in search for food. At night, they may also be active,2 but are generally sleeping under or wedged into coral or rock ledges.8

What does the Hawksbill Turtle eat? Adult Hawksbill Sea Turtles feed mostly on sea sponges (which account for 90–95% of their diet),3 but also on a variety of other bottom dwelling animals (like sea urchins, crabs, and squid) and even plant material.3,4,7,8,10

What is tortoise shell? Tortoise shell or turtle shell is an ornamental material used to make jewelry and souvenirs, particularly hair combs and frames for eyeglasses. It is produced from the shell of some turtle species, most notably the Hawksbill. The commercial exploitation of this material was the main driver behind the worldwide catastrophic decline of Hawksbill Turtle populations.

What would happen if the Hawksbill Turtle went extinct? If Hawksbill Sea Turtles went extinct, the populations of the organims they feed on, such as sponges and sea urchins, would likely explode, causing large-scale erosion54,55 and even the collapse of marine ecosystems such as coral reefs.

Where do Hawksbill Sea Turtles live? Hawksbill Sea Turtles occur throughout the entire tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. The adults prefer insular coral reefs, rocky outcrops, banks, lagoons, and mangrove estuaries.8,9

Why are Hawksbill Turtles going extinct? Hawksbill Sea Turtles are considered to be facing imminent risk of extinction beacause their populations have declined 84–87% over the past three generations as a result of over-exploitation, incidental mortality due to interactions fisheries, and degradation of marine and nesting habitats.48

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Juan José Alava.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin Jm (2020) Eretmochelys imbricata. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Van Houtan KS, Francke DL, Alessi S, Jones TT, Martin SL, Kurpita L, King CS, Baird RW (2016) The developmental biogeography of hawksbill sea turtles in the North Pacific. Ecology and Evolution 6: 2378–2389.

- NOAA (2013) Hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, 87 pp.

- Bjorndal KA (1997) Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles. In: Musick JA, Lutz PL (Eds) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 199–231.

- Carr A, Hirth H, Ogren L (1966) The ecology and migration of sea turtles, 6. The hawksbill turtle in the Caribbean Sea. American Museum Novitates 2248: 1–29.

- Al Kiyumi AA, Al Saady SM, Mendonca VM, Grobler H, Erzini K (2005) Natural predation on eggs and hatchlings of hawksbill turtles Eretmochelys imbricata on Al Dimaniyat Islands, Gulf of Oman. Proceedings of the 21st International Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation 528: 90–91.

- Limpus CJ, Miller JD (2008) Final report for Australian hawksbill turtle population dynamics project. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, 130 pp.

- Márquez R (1990) Sea turtles of the world. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 81 pp.

- Witzell W (1983) Synopsis of biological data on the hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) (Linnaeus, 1766). FAO Fisheries Synopsis Number 137: 1–78.

- Gaos AR, Lewison RL, Yañez IL, Wallace BP, Liles MJ, Nichols WJ, Baquero A, Hasbún CR, Vásquez M, Urteaga J, Seminoff JA (2012) Shifting the life-history paradigm: discovery of novel habitat use by hawksbill turtles. Biology Letters 8: 54–56.

- Bell I (2012) Algivory in hawksbill turtles: Eretmochelys imbricata food selection within a foraging area on the Northern Great Barrier Reef. Marine Ecology 34: 43–55.

- Gruber DF, Sparks JS (2015) First observation of fluorescence in marine turtles. American Museum Novitates 3845: 1–8.

- van Dam RP, Diez CE (1996) Diving behavior of immature hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata) in a Caribbean cliff-wall habitat. Marine Biology 127: 171–178.

- Blumenthal JM, Austin TJ, Bothwell JB, Broderick AC, Ebanks-Petrie G, Olynik JR, Orr MF, Solomon JL, Witt MJ, Godley BJ (2008) Diving behavior and movements of juvenile hawksbill turtles Eretmochelys imbricata on a Caribbean coral reef. Coral Reefs 28: 55–65.

- Nivière M, Chambault P, Pérez T, Etienne D, Bonola M, Martin J, Barnérias C, Védie F, Mailles J, Dumont-Dayot E, Gresser J, Hiélard G, Régis S, Lecerf N, Thieulle L, Duru M, Lefebvre F, Milet G, Guillemot D, Bildan D, de Montgolfier B, Benhalilou A, Murgale C, Maillet T, Queneherve P, Woignier T, Safi M, Le Maho Y, Petit O, Chevallier D (2018) Identification of marine key areas across the Caribbean to ensure the conservation of the critically endangered hawksbill turtle. Biological Conservation 223: 170–180.

- Meylan A (1988) Spongivory in hawksbill turtles: a diet of glass. Science 239: 393–395.

- Limpus CJ, Miller JD (2008) Final report for Australian hawksbill turtle population dynamics project. Environmental Protection Agency, Brisbane, 130 pp.

- Parrish F (1958) Miscellaneous observations on the behavior of captive sea turtles, Bulletin of Marine Science of the Gulf and Caribbean 8: 348–355.

- Luschi P, Benhamou S, Girard C, Ciccione S, Roos D, Sudre J, Benvenuti S (2007) Marine turtles use geomagnetic cues during open-sea homing. Current Biology 17: 126–133.

- Bellini C, Sanches TM, Formia A (2000) Hawksbill tagged in Brazil captured in Gabon, Africa. Marine Turtle Newsletter 87: 11–12.

- CIT (2006) Informe Anual 2006. Convención Interamericana para la Protección y Conservación de las Tortugas Marinas, Puerto Ayora, 22 pp.

- Gaos AR, Lewison RL, Jensen MP, Liles MJ, Henriquez A, Chavarria S, Pacheco CM, Valle M, Melero D, Gadea V, Altamirano E, Torres P, Vallejo F, Miranda C, LeMarie C, Lucero J, Oceguera K, Chácon D, Fonseca L, Abrego M, Seminoff JA, Flores EE, Llamas I, Donadi R, Peña B, Muñoz JP, Ruales DA, Chaves JA, Otterstrom S, Zavala A, Hart CE, Brittain R, Alfaro-Shigueto J, Mangel J, Yañez IL, Dutton PH (2017) Natal foraging philopatry in eastern Pacific hawksbill turtles. Royal Society Open Science 4: 170153.

- Baquero A, Peña M, Muñoz P, Alvarez V (2008) Sea turtles nesting in Machalilla National Park beaches in 2008: a new nesting ground for Hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Eastern Pacific. Proceedings of the II South Eastern Pacific Sea Turtle Symposium 2: 21–25.

- Alava JJ, Barragán MJ (2017) The missing hawksbills (Eretmochelys imbricata) from the Guayaquil Gulf, Ecuador: Novel occurrence and conservation implications. The Journal of Marine Animals & Their Ecology 9: 6–12.

- Blumenthal JM, Austin TJ, Bell CDL, Bothwell JB, Broderick AC, Ebanks-Petrie G, Gibb GA, Luke KE, Olynik JR, Orr MF, Solomon JL, Godley BJ (2009) Ecology of hawksbill turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata on a western Caribbean foraging ground. Chelonian Conservation and Biology 8: 1–10.

- Karl SA, Bowen BW, Avise JC (1995) Hybridization among the ancient mariners: characterization of marine turtle hybrids with molecular genetic assays. Journal of Heredity 86: 262–268.

- Kelez S, Velez-Zuazo X, Pacheco AS (2016) First record of hybridization between green Chelonia mydas and hawksbill Eretmochelys imbricata sea turtles in the Southeast Pacific. PeerJ 4: e1712.

- Lara-Ruiz P, Lopez GG, Santos FR, Soares LS (2006) Extensive hybridization in hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) nesting in Brazil revealed by mtDNA analyses. Conservation Genetics 7: 773–781.

- Phillips KP, Jorgensen TH, Jolliffe KG, Jolliffe SM, Henwood J, Richardson DS (2013) Reconstructing paternal genotypes to infer patterns of sperm storage and sexual selection in the hawksbill turtle. Molecular Ecology 22: 2301–2312.

- González-Garza BI, Stow A, Sánchez-Teyer LF, Zapata-Pérez O (2015) Genetic variation, multiple paternity, and measures of reproductive success in the critically endangered hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata). Ecology and Evolution 5: 5758–5769.

- Bowen BW, Karl SA (2007) Population genetics and phylogeography of sea turtles. Molecular Ecology 16: 4886–4907.

- Peña-Mosquera MP, Baquero-Gallegos AB, Muñoz-Pérez JM, Puebla-Jiménez F, Alvarez V, Chalen-Noroña X (2009) El Parque Nacional Machalilla: zona crítica de anidación para la tortuga carey (Eretmochelys imbricata) y verde (Chelonia mydas) en el Ecuador y el Pacífico Oriental. Temporadas 2007–2009. Fundación Equilibrio Azul, Quito, 7 pp.

- Green D, Ortiz-Crespo F (1981) The status of sea turtle populations in the central eastern Pacific. In: Bjorndal K (Ed) Biology and conservation of sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. and London, 221–233.

- Varela RG, Zamora G, Harrison E (2015) Report on the 2014 green turtle program at Tortuguero, Costa Rica. Sea Turtle Conservancy, Gainesville, 54 pp.

- Horrocks JA, Scott NM (1991) Nest site location and nest success in the hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata in Barbados, West Indies. Marine Ecology Progress Series 69: 1–8.

- Hitchins PM, Bourquin O, Hitchins S (2006) Distances covered and times taken for nesting of hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata), Cousine Island, Seychelles. Phelsuma 13: 93–101.

- Beggs JB, Horrocks JA, Krueger BH (2007) Increase in hawksbill sea turtle Eretmochelys imbricata nesting in Barbados, West Indies. Endangered Species Research 3: 159–168.

- Mrosovsky N (1994) Sex ratios of sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270: 16–27.

- Vaughan P (1981) Marine turtles: a review of their status and management in the Salomon Islands. Ministry of Natural Resources, Honiara, 70 pp.

- Boulon RH (1994) Growth rates of wild juvenile hawksbill turtles, Eretmochelys imbricata, in St. Thomas, United States Virgin Islands. Copeia 1994: 811–814.

- Witzell WN (1987) Selective predation on large Cheloniid sea turtles by tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier). Japanese Journal of Herpetology 12: 22–29.

- Randall J (1967) Food habits of reef fishes of the West Indies. Studies in Tropical Oceanography Miami 5: 665–847.

- Pritchard P (1977) Marine turtles of Micronesia. Chelonia Press, San Francisco, 83 pp.

- Arroyo-Arce S, Salom-Pérez R (2015) Impact of jaguar Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) predation on marine turtle populations in Tortuguero, Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical 63: 815–825.

- De Carvalho RH, Lacerda PD, da Silva Mendes S, Barbosa BC, Paschoalini M, Prezoto F, de Sousa BM (2015) Marine debris ingestion by sea turtles (Testudines) on the Brazilian coast: an underestimated threat? Marine Pollution Bulletin 101: 746–749.

- Ylitalo GM, Collier TK, Anulacion BF, Juaire K, Boyer RH, da Silva DAM, Keene JL, Stacy BA (2017) Determining oil and dispersant exposure in sea turtles from the northern Gulf of Mexico resulting from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Endangered Species Research 33: 9–24.

- Werneck MR, Lima EH, Pires T, Silva RJ (2015) Helminth parasites of the juvenile hawksbill turtle Eretmochelys imbricata (Testudines: Cheloniidae) in Brazil. Journal of Parasitology 101: 500–503.

- Göpper BM, Voogt NM, Ganswindt A (2018) First record of the marine turtle leech (Ozobranchus margoi) on hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the inner granitic Seychelles. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research 85: 1–3.

- Mortimer JA, Donnelly M (2008) Eretmochelys imbricata. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Dei Marcovaldi MAG, Santos AJB, Santos AS, Soares LS, Lopez GG, Godfrey MH, López-Mendilaharsu M, Fuentes MMPB (2014) Spatio-temporal variation in the incubation duration and sex ratio of hawksbill hatchlings: Implication for future management. Journal of Thermal Biology 44: 70–77.

- Kamel SJ, Mrosovsky N (2006) Deforestation: risk of sex ratio distortion in hawksbill sea turtles. Ecological Applications 16: 923–931.

- Fish MR, Cote IM, Horrocks JA, Mulligan B, Watkinson AR, Jones AP (2008) Construction setback regulations and sea level rise: mitigating sea turtle nesting beach loss. Ocean and Coastal Management 51: 330–341.

- Fish MR, Cote IM, Gill JA, Jones AP, Renshoff S, Watkinson AR (2005) Predicting the impact of sea-level rise on Caribbean sea turtle nesting habitat. Conservation Biology 19: 482–491.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- De Bakker DM, Webb AE, van den Bogaart LA, van Heuven SMAC, Meesters EH, van Duyl FC (2018) Quantification of chemical and mechanical bioerosion rates of six Caribbean excavating sponge species found on the coral reefs of Curaçao. PLOS ONE 13: e0197824.

- Ling S (2009) Climate change and a range‐extending sea urchin: catastrophic‐shifts and resilience in a temperate reef ecosystem. PhD thesis, Australia, University of Tasmania.