Green Sea Turtle |

Reptiles of Ecuador | Testudines | Cheloniidae | Chelonia mydas

English common names: Green Sea Turtle, Pacific Green Turtle, Black Turtle.

Spanish common name: Tortuga verde, tortuga prieta, tortuga negra.

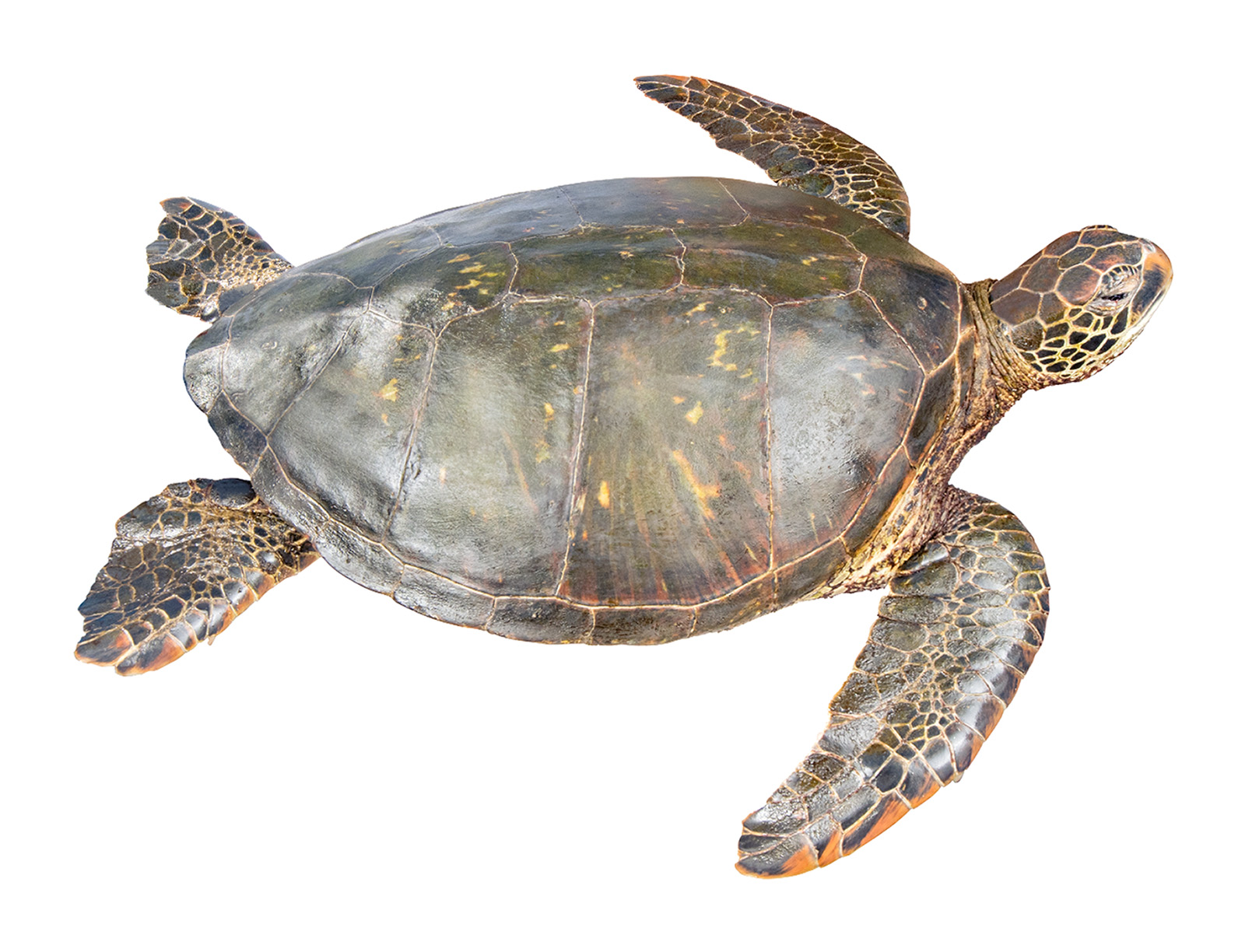

Recognition: ♂♂ 104.1 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace. ♀♀ 153 cmThis is a measurement of the straight length of the carapace.. The Green Sea Turtle (Chelonia mydas) may be distinguished from other sea turtles by having four pairs of costal shields, one pair of prefrontal scales, and non-overlapping carapace shields. Males are distinguished from females by having longer, thicker tails. In the Galápagos Archipelago, two genetically distinct morphs of Chelonia mydas coexist: the black morph and the yellow morph. Black Turtles are dark olive green in coloration and are larger than Yellow Turtles, which are light orangish brown in coloration.

Picture: Adult female, yellow morph. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Subadult female, yellow morph. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female. Parque Nacional Machalilla. Manabí, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult female, black morph. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male, black morph. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

Picture: Adult male, black morph. San Cristóbal Island. Galápagos, Ecuador. | |

| |

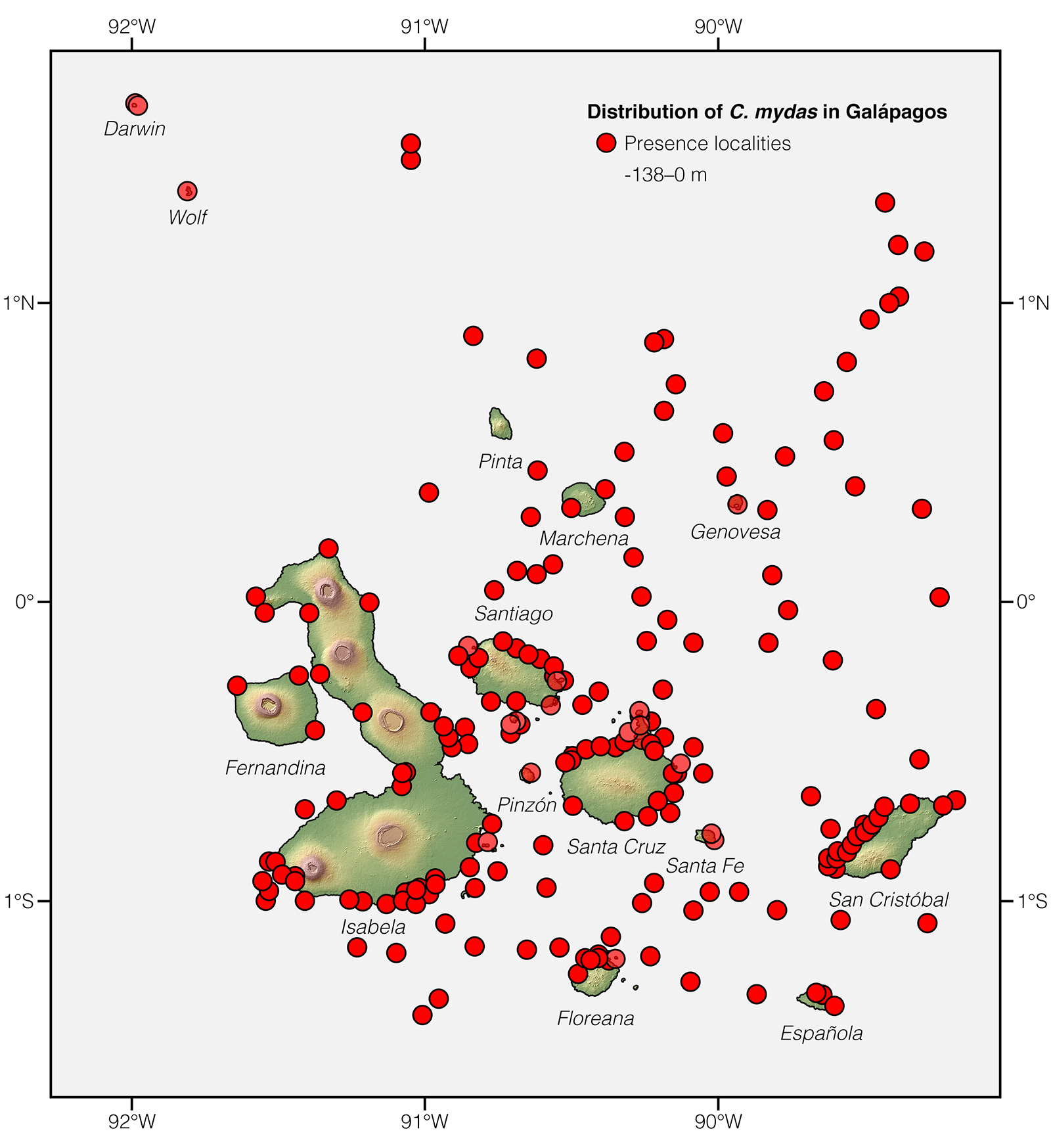

Natural history: Extremely common. Chelonia mydas is the most common sea turtle in Galápagos1 and the second most common along the coast of mainland Ecuador.2 In Galápagos, turtles of the black morph are generally more abundant than those of the yellow morph. After hatching on tropical beaches, hatchlings of the Green Sea Turtle frantically swim for 1–3 days in an offshore direction until they reach open ocean "nursery" habitats where they spend 3–10 years3 actively swimming and drifting day and night along with surface currents.4 During this early stage, they are mainly carnivorous,5 feeding on comb jellies, pelagic tunicates, worms, mollusks, crustaceans, and insects, but also on seagrasses and algae.6,7

Green Sea Turtle hatchlings worldwide are preyed upon by a variety of mammals (including pigs, foxes, cats, mongooses, coatis, and rats), birds (such as sea birds, vultures, and crows), snakes, sharks, fish, and crabs.1,8 When they reach 20–35 cm in length, they establish their home ranges in shallower waters near the coast,5 where they become largely herbivorous,5 spending most of the day around areas of good pasturage, grazing on a variety of seagrass and algae species7 as well as on leaves, tree bark, saltgrass, and animal matter such as tube worms, crustaceans, bryozoans, fish and their eggs, tunicates, jellyfish, echinoderms, mollusks, and sea sponges.8–11

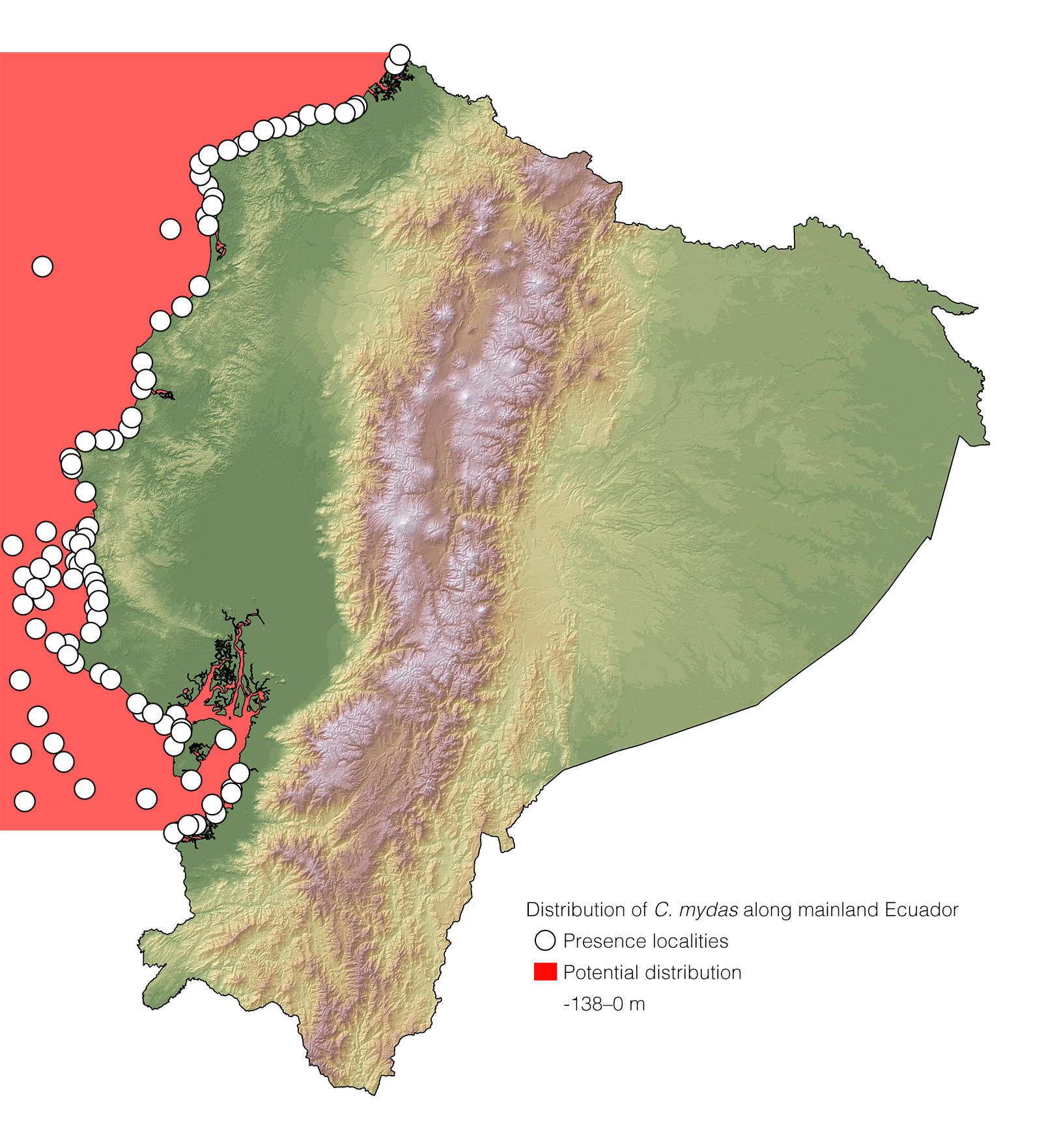

Green Sea Turtles spend most of the day conducting shallow (less than 20 m deep) dives12 and resting on the water surface,13 but they can dive down to 138 m in depth14 and for up to 70 minutes.15 Occasionally, adults bask on shore16 during the daytime if sea surface temperatures fall below 23°C.17 At night, they rest near the surface,13 or on the sea bottom, or among rocks or coral crags18 at a depth of 18–20 m.12 Some adults of Chelonia mydas are permanent residents of coastal waters (usually within 15 km from the nesting beaches), while others are migratory,18 traveling up to 90 km per day,19 and up to a total of 8,283 km to distant foraging grounds.20 Using geomagnetic cues,21 females routinely travel thousands of kilometers to return to nest at or near the same beaches season after season, which may also be the same beaches on which they themselves hatched.22

In the Galápagos Archipelago, some Pacific Green Turtles, also known as Black Turtles, reside permanently around the islands, but others migrate, either into oceanic waters, or into shallow foraging waters near mainland Central and South America.23,24 Most Green Sea Turtles on the coast of mainland Ecuador breed and feed locally,25,26 but some also travel to Galápagos and presumably elsewhere along the eastern Pacific.27,28 Turtles of the yellow morph do not nest in Galápagos; they do so in nesting grounds in the Indo-Pacific.

Green Sea Turtles become sexually mature around 17–19 years old. From this age onwards, they gather in polygamous29 breeding rookeries within ~1 km from the nesting beaches,30 where pairs may copulate for up to 6–24 hours.1 Hybridization between Chelonia mydas and other sea turtle species such as Caretta caretta,31 Eretmochelys imbricata,32 and Lepidochelys olivacea,32 occurs. Females of the Green Sea Turtle are capable of storing sperm throughout the breeding season,29 and the resulting clutches may be sired by multiple males.29 They nest every 2–4 years19 on roughly (0.4–1.2 km apart)8 the same beaches.

In Ecuador, Black Turtles nest throughout the year,1 but most nest from November to May with a peak from February to March.30,33 During a single season, females may lay 1–9 clutches19,34 at intervals of 5–25 days.35 They produce 18–226 eggs8 per clutch and lay them on sandy beaches in 56–77 cm deep nests,18,36 usually at night.18 Nesting emergences last 2–3 hours.8 During these events, female Green Sea Turtles are very shy, and can easily be scared back into the sea.8 Nesting may be solitary (as it is in Ecuador) or in huge aggregations, with up to 11,755 females nesting in the same area during a single night.37 The incubation period is 40–99 days,7 and 1–89.9% of the eggs laid on Ecuadorian beaches hatch.1,30 Temperature determines the sex of the offspring,38 and the proportion of female hatchlings increases with the incubation temperature.39 Nest temperatures >30.3ºC produce females and temperatures <28.5ºC generate males.40

Eggs of Pacific Green Turtles in Galápagos are mostly preyed upon by pigs and beetles.1,41 On mainland Ecuador, they are eaten by dogs and raccoons.42 Worldwide, they are preyed upon by a variety of mammals (including peccaries, pigs, dogs, foxes, jackals, opossums, raccoons, coatis, and rats), birds (including birds of prey, vultures, ibises, and crows) monitor lizards, crabs, beetles, and ants.8,35,43 They are also occasionally lost to flooding44 and disturbance by other nesting turtles, in addition to being widely used for human consumption.45 The eggs of Chelonia mydas hatch synchronously46 and usually at night.1,18 During emergence, the presence of artificial lighting affects the orientation of hatchlings,47 which may result in mortality caused by traffic. It is estimated that only 1–3% of hatchlings survive into adulthood.8

In addition to predation by sharks,48 crocodiles,7 and jaguars,49 causes of mortality for adult Green Sea Turtles include ingestion of plastic,50 collision with boats,51–53 interactions with fishing gear,54,55 direct harvesting for meat consumption (although their meat may cause food poisoning),2,45 oil spills,55 red tides,56 and cyclones.7 Individuals of Chelonia mydas are parasitized by a variety of worms and leeches, and colonized by remoras, barnacles, crabs, amphipods, mussels, isopods, sea snails, hydrozoans, bryozoans, and algae.7,8 The lifespan of individuals of C. mydas in the wild is about 80 years, but, based on growth rates,57 we estimate a maximum lifespan of 118 years.

Conservation: Endangered.58 Chelonia mydas is listed in this category because its populations have declined 48–67% over the past three generations as a result of the direct harvesting of eggs and adults, incidental mortality due to interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, and the degradation of marine and nesting habitats.58 Another threat faced by C. mydas is climate change. Since temperature during incubation determines the sex of the offspring,38 the increase of the average global temperature may result in the complete feminization of some populations.39 Under some scenarios of global sea level rise, up to 60% of clutches on some nesting beaches may be lost to flooding by 2100.59

Distribution: Green Sea Turtles occur throughout the entire tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. The morph known as Black Turtle is restricted to the Pacific Ocean.

Etymology: The generic name Chelonia comes from the Greek word chelone (meaning “turtle”).60 The specific epithet mydas is a reference to the Greek king Midas, who had the ability to turn everything he touched into gold.60

See it in the wild: Individuals of Chelonia mydas can be seen year-round with ~80–100% certainty in shallow waters throughout Galápagos. Swimming Green Sea Turtles can be easily observed from the coast, while snorkeling or diving, or from boats going to and from tourism sites. Along the coast of mainland Ecuador, the Green Sea Turtle is harder to see. Although the species nests roughly on the same beaches during the same months, witnessing such events is rare. However, swimming Chelonia mydas can be seen with ~60–80% certainty in shallow waters off Machalilla National Park, especially in Isla de la Plata.

FAQ

Do sharks eat Green Sea Turtles? Yes.48 Sharks are among the few predators of adult Green Sea Turtles.

Do Green Sea Turtles bite? Yes. Although Green Sea Turtles do not feed on humans, there have been cases of turtles biting swimmers.61 These bites may be painful, but are not life-threatening.

How big do Green Sea Turtles get? Green Sea Turtles can grow up to 1.53 m in straight carapace length.

How fast do Green Sea Turtles swim? Green Sea Turtles can swim at a speed of 3.6 km/h over short distances62 and they can maintain a long-distance cruising speed of up to 65 km/d.63 Michael Phelps' top swimming speed is 9.7 km/h.

How long do Green Sea Turtles live? The average lifespan of Green Sea Turtles in the wild is about 80 years, but, based on growth rates,57 they may live up to 118 years.

What does a Green Sea Turtle eat? Green Sea Turtles are mainly herbivores, feeding mostly on seagrass and algae species, but also on leaves, tree bark, saltgrass, and animal matter.8–11

When and where do Green Sea Turtles sleep? Green Turtles usually sleep at night. They do so near the surface,13 on the sea bottom, or among rocks or coral crags18 at a depth of 18–20 m.12

Where do Green Sea Turtles come from? Green Sea Turtles occur throughout the entire tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific oceans. The morph known as Black Turtle is restricted to the Pacific Ocean. The morph known as Black Turtle is restricted to the Pacific Ocean, whereas the morph known as Yellow Turtle comes from nesting grounds in the Indo-Pacific.

Why are Green Sea Turtles Endangered? Green Sea Turtles are classified as Endangered because their populations have declined 48–67% as a result of the direct harvesting of eggs and adults, incidental mortality due to interactions with artisanal and industrial fisheries, and the degradation of marine and nesting habitats.58

Why are Green Sea Turtles green? The skin and carapace of Green Sea Turtles is not really green, but reddish brown or dark olive. The green color comes from algae living on the turtles. However, Green Sea Turtles are named after their greenish-colored fat, which is believed to be a result of their herbivorous diet.

Special thanks to Jack W. Sites, Jr. for symbolically adopting the Green Sea Turtle and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Graeme Hays and Juan José Alava.

Photographers: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Chelonia mydas. In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com

Literature cited:

- Green D (1983) Galápagos sea turtles. Noticias de Galápagos 38: 22–25.

- Herrera M, Coello D (2010) Tortugas marinas en el Ecuador: playas de anidación, amenazas naturales y antropogénicas. Instituto Nacional de Pesca, Guayaquil, 33 pp.

- Reich KJ, Bjorndal KA, Bolten AB (2007) The 'lost years' of green turtles: using stable isotopes to study cryptic lifestages. Biology Letters 3: 712–714.

- Putman NF, Mansfield KL (2015) Direct evidence of swimming demonstrates active dispersal in the sea turtle "lost years." Current Biology: 25: 1221–1227.

- Bjorndal KA (1997) Foraging ecology and nutrition of sea turtles. In: Musick JA, Lutz PL (Eds) The biology of sea turtles. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 199–231.

- SWOT (2019) Green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas. The State of the World's Sea Turtles. Available from: https://www.seaturtlestatus.org

- Hirth H (1997) Synopsis of the biological data on the green turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus 1758). Biological Report 97: 1–120.

- Hirth H (1971) Synopsis of biological data on the green turtle Chelonia mydas (Linnaeus 1758). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, 128 pp.

- Slevin JR (1935) An account of the reptiles inhabiting the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the New York Zoological Society 38: 3–24.

- Seminoff JA (2000) Biology of the East Pacific green turtle, Chelonia mydas agassizii, at a temperate feeding area in the Gulf of California, Mexico. PhD thesis, Tucson, United States, University of Arizona.

- Carrión-Cortez JA, Zárate P, Seminoff JA (2010) Feeding ecology of the green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) in the Galápagos Islands. Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom 90: 1005–1013.

- Hays GC, Adams CR, Broderick AC, Godley BJ, Lucas DJ, Metcalfe JD, Prior AA (2000) The diving behaviour of green turtles at Ascension island. Animal Behaviour 59: 577–586.

- Blanco GS, Morreale SJ, Seminoff JA, Paladino FV, Piedra R, Spotila JR (2012) Movements and diving behavior of internesting green turtles along Pacific Costa Rica. Integrative Zoology 8: 293–306.

- Rice MR, Balazs GH (2008) Diving behavior of the Hawaiian green turtle (Chelonia mydas) during oceanic migrations. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 356: 121–127.

- Chambault P, Pinaud D, Vantrepotte V, Kelle L, Entraygues M, Guinet C, Berzins R, Bilo K, Gaspar P, de Thoisy B, Le Maho Y, Chevallier D (2015) Dispersal and diving adjustments of the green turtle Chelonia mydas in response to dynamic environmental conditions during post-nesting migration. PLoS ONE 10: e0137340.

- Fritts TH (1981) Marine turtles of the Galápagos Islands and adjacent areas of the Eastern Pacific on the basis of observations made by J. R. Slevin 1905-1906. Journal of Herpetology 15: 293–301.

- Van Houtan KS, Halley JM, Marks W (2015) Terrestrial basking sea turtles are responding to spatio-temporal sea surface temperature patterns. Biology Letters 11: 20140744.

- Carr A, Ogre L (1960) The ecology and migration of sea turtles, 4. The green turtle in the Caribbean Sea. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 121: 1–48.

- Carr A, Carr MH, Meylan AB (1978) The ecology and migrations of sea turtles, 7. The West Caribbean sea turtle colony. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 162: 1–46.

- Robinson DP, Jabado RW, Rohner CA, Pierce SJ, Hyland KP, Baverstock WR (2017) Satellite tagging of rehabilitated green sea turtles Chelonia mydas from the United Arab Emirates, including the longest tracked journey for the species. PLoS ONE 12: e0184286.

- Luschi P, Benhamou S, Girard C, Ciccione S, Roos D, Sudre J, Benvenuti S (2007) Marine turtles use geomagnetic cues during open-sea homing. Current Biology 17: 126–133.

- Hendrickson JR (1958) The green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas (Linn.) in Malaya and Sarawak. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London 130: 455–535.

- Seminoff JA, Zárate P, Coyne M, Foley DG, Parker D, Lyon BN, Dutton PH (2008) Post-nesting migrations of Galápagos green turtles Chelonia mydas in relation to oceanographic conditions: integrating satellite telemetry with remotely sensed ocean data. Endangered Species Research 4: 57–72.

- Muñoz JP (2013) Home ranges and movements of adult male green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) in San Cristóbal Island, Galápagos, Ecuador. MSc thesis, Townsville, Australia, James Cook University.

- Mizobe C, Contreras-López M (2014) Anidación de tortugas marinas en la provincia de Manabí, Ecuador. Revista La Técnica 12: 38–55.

- Chaves JA, Peña M, Valdés-Uribe JA, Muñoz-Pérez JP, Vallejo F, Heidemeyer M, Torres-Carvajal O (2017) Connectivity, population structure, and conservation of Ecuadorian green sea turtles. Endangered Species Research 32: 251–264.

- Green D (1984) Long-distance movements of Galápagos Green Turtles. Journal of Herpetology 18: 121–130.

- Dutton PH, Jensen MP, Frey A, LaCasella E, Balazs GH, Zárate P, Chassin-Noria O, Sarti-Martinez AL, Velez E (2014) Population structure and phylogeography reveal pathways of colonization by a migratory marine reptile (Chelonia mydas) in the central and eastern Pacific. Ecology and Evolution 4: 4317–4331.

- Pearse DE, Avise JC (2001) Turtle mating systems: behavior, sperm storage, and genetic paternity. Journal of Heredity 92: 206–211.

- Zárate P, Dutton P (2002) Tortuga verde. In: Danulat E, Edgar GJ (Eds) Reserva Marina de Galápagos. Línea base de la biodiversidad. Fundación Charles Darwin, Puerto Ayora, 305–323.

- James MC, Martin K, Dutton PH (2004) Hybridization between a green turtle, Chelonia mydas, and loggerhead turtle, Caretta caretta, and the first record of a green turtle in Atlantic Canada. The Canadian Field-Naturalist 118: 579–582.

- Seminoff JA, Karl SA, Schwartz T, Resendiz A (2003) Hybridization of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) in the Pacific Ocean: indication of an absence of gender bias in the directionality of crosses. Bulletin of Marine Science 73: 643–652.

- Green D, Ortiz-Crespo F (1981) Status of sea turtle populations in the Central Eastern Pacific. In: Bjorndal K (Ed) Biology and conservation of sea turtles. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington D.C. and London, 221–233.

- Chen TH, Cheng IJ (1995) Breeding biology of the green turtle, Chelonia mydas, (Reptilia: Cheloniidae) on Wan-An Island, Peng-Hu Archipelago, Taiwan. I. Nesting ecology. Marine Biology 124: 9–15.

- Zárate P, Fernie A, Dutton P (2003) First results of the East Pacific green turtle, Chelonia mydas, nesting population assessment in the Galápagos Islands. Annual Symposium on Sea Turtle Biology and Conservation 22: 70–73.

- Gomuttapong S, Klom-In W, Kitana J, Pariyanonth P, Thirakhupt K, Kitana N (2013) Green turtle, Chelonia mydas, nesting and temperature profile of the nesting beach at Huyong Island, the Similan Islands in Andaman Sea. Natural Resources 4: 357–361.

- Limpus CJ, Miller JD, Parmenter CJ, Limpus DJ (2003) The Green Turtle, Chelonia mydas, population of Raine Island and the northern Great Barrier Reef. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 49: 349–440.

- Mrosovsky N (1994) Sex ratios of sea turtles. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 270: 16–27.

- Jensen MP, Allen CD, Eguchi T, Bell IP, LaCasella EL, Hilton WA, Hof CAM, Dutton PH (2018) Environmental warming and feminization of one of the largest sea turtle populations in the world. Current Biology 28: 154–159.

- Spotila JR, Standora EA, Morreale SJ, Ruiz GJ (1987) Temperature dependent sex determination in the green turtle (Chelonia mydas): effects on the sex ration on a natural nesting beach. Herpetologica 43: 74–81.

- Zárate P, Cahoon SS, Contato MCD, Dutton PH, Seminoff JA (2006) Nesting beach monitoring of green turtles in the Galapagos Islands: a 4-year evaluation. Abstracts of the 26th Sea Turtle Symposium 26: 3–8.

- Alava JJ (2000) Current conservation status of sea turtles in Ecuador. In: Amorocho D, Campo F, Riascos JA, Parra E (Eds) Proceedings of the Workshop about Biology and Conservation of Sea Turtles and III International Seminar of the Colombian Network for the Sea Turtles Conservation. RETOMAR–WIDECAST, Colombia, 51–58.

- Wetterer JK, Wood LD, Johnson C, Krahe H, Fitchett S (2007) Predaceous ants, beach replenishment, and nest placementby sea turtles. Environmental Entomology 36: 1084–1091.

- Anastácio R, Santos C, Lopes C, Moreira H, Souto L, Ferrão J Garnier J, Pereira MJ (2014) Reproductive biology and genetic diversity of the green turtle (Chelonia mydas) in Vamizi island, Mozambique. SpringerPlus 3: 540.

- Groombridge B, Luxmoore R (1989) The green turtle and hawksbill turtle (Reptilia: Cheloniidae) world status, exploitation and trade. CITES, Lausanne, 601 pp.

- Santos RG, Pinheiro HT, Martins AS, Riul P, Bruno SC, Janzen FJ, Ioannou CC (2016) The anti-predator role of within-nest emergence synchrony in sea turtle hatchlings. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 283: 20160697.

- Thums M, Whiting SD, Reisser J, Pendoley KL, Pattiaratchi CB, Proietti M, Hetzel Y, Fisher R, Meekan MG (2016) Artificial light on water attracts turtle hatchlings during their near shore transit. Royal Society Open Science 3: 160142.

- Witzell WN (1987) Selective predation on large Cheloniid sea turtles by tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier). Japanese Journal of Herpetology 12: 22–29.

- Arroyo-Arce S, Salom-Pérez R (2015) Impact of jaguar Panthera onca (Carnivora: Felidae) predation on marine turtle populations in Tortuguero, Caribbean coast of Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical 63: 815–825.

- De Carvalho RH, Lacerda PD, da Silva Mendes S, Barbosa BC, Paschoalini M, Prezoto F, de Sousa BM (2015) Marine debris ingestion by sea turtles (Testudines) on the Brazilian coast: an underestimated threat? Marine Pollution Bulletin 101: 746–749.

- Zárate P (2009) Amenazas para las tortugas marinas que habitan el archipiélago de Galápagos. Fundación Charles Darwin, Puerto Ayora, 50 pp.

- Parra M, Deem SL, Espinoza E (2011) Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) mortality in the Galápagos Islands, Ecuador during the 2009–2010 nesting season. Marine Turtle Newsletter 130: 10–15.

- Denkinger J, Parra M, Muñoz JP, Carrasco C, Murillo JC, Espinosa E, Rubianes F, Koch V (2013) Are boat strikes a threat to sea turtles in the Galápagos Marine Reserve? Ocean & Coastal Management 80: 29–35.

- Yaghmour F, Al Bousi M, Whittington-Jones B, Pereira J, García-Nuñez S, Budd J (2018) Impacts of the traditional baited basket fishing trap “gargoor” on green sea turtles Chelonia mydas (Testudines: Cheloniidae) Linnaeus, 1758 from two case reports in the United Arab Emirates. Marine Pollution Bulletin 135: 521–524.

- Orós J, Torrent A, Calabuig P, Déniz S (2005) Diseases and causes of mortality among sea turtles stranded in the Canary Islands, Spain (1998-2001). Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 63: 13–24.

- Foley AM, Stacy BA, Schueller P, Flewelling LJ, Schroeder B, Minch K, Fauquier DA, Foote JJ, Manire CA, Atwood KE, Granholm AA, Landsberg JH (2019) Assessing Karenia brevis red tide as a mortality factor of sea turtles in Florida, USA. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 132: 109–124.

- Goshe LR (2009) Age at maturation and growth rates of green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) along the southeastern U.S. Atlantic coast estimated using skeletochronology. MSc thesis, Wilmington, United States, University of North Carolina.

- Seminoff JA (2004) Chelonia mydas. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Varela MR, Patrício AR, Anderson K, Broderick AC, DeBell L, Hawkes LA, Tilley D, Snape RTE, Westoby MJ, Godley BJ (2018) Assessing climate change associated sea level rise impacts on sea turtle nesting beaches using drones, photogrammetry and a novel GPS system. Global Change Biology 5: 753–762.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- SESL Australia (2019) Turtle bites woman! Available from: https://sesl.com.au

- Prange HD (1976) Energetics of swimming of a sea turtle. Journal of Experimental Biology 64: 1–12.

- Shultz JP (1975) Sea turtles nesting in Surinam. Zoologische Verhandelingen 143: 1–44.