Published May 12, 2018. Updated April 13, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Welborn’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas welborni)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Dipsas welborni

English common name: Welborn’s Snail-eating Snake.

Spanish common name: Caracolera de David Welborn.

Recognition: ♂♂ 73.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=54.2 cm. ♀♀ 87.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=59.5 cm..1 Dipsas welborni is the only snake in its area of distribution having the following combination of characters: dorsal scales arranged in 13 rows at mid-body, vertebral scale row distinctively wider than adjacent rows, light brown (yellow in juveniles) dorsum with black to dark-brown blotches, and head strongly vermiculated with light yellowish pigment (Fig. 1).1 This species differs from D. indica by having a pointed, instead of blunt, snout and a brown, instead of gray, dorsum.2 From D. vermiculata, it differs by having two prefrontal scales (instead of a single one).1

Figure 1: Adult female of Dipsas welborni from Vía a Nuevo Paraíso, Zamora Chinchipe province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Dipsas welborni is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed rainforests and cloud forests, occurring in lower densities, or not at all, in forest-edge situations.1 Welborn’s Snail-eating Snakes are active at night, especially if it is raining or drizzling.1,3 Their movements through the foliage are slow, graceful, and generally occur during the first hours of the night on vegetation 0.2–3.5 m above the ground.1,3 Nothing is known about the diet in this species, but snakes of the genus Dipsas in general feed almost exclusively on snails and slugs. Although some snail-eaters produce saliva that is toxic to mollusks,4 these snakes are considered harmless to humans. They never attempt to bite, resorting instead to musking and flattening the body while expanding the head to simulate a triangular shape.3,5

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..1 Dipsas welborni is listed in this category because the species is distributed over a region of the Amazonian slopes of the Andes that holds large areas of continuous unspoiled forest. In Ecuador, approximately 76% of the species’ forest habitat is still standing. Unfortunately, vast areas of the Cordillera del Cóndor, notably on the northern part of the species’ range, are being cleared to make room for large-scale open-pit mining operations.1 However, since D. welborni occurs over an area greater than 20,000 km2, the species does not meet the criteria for a threatened category.

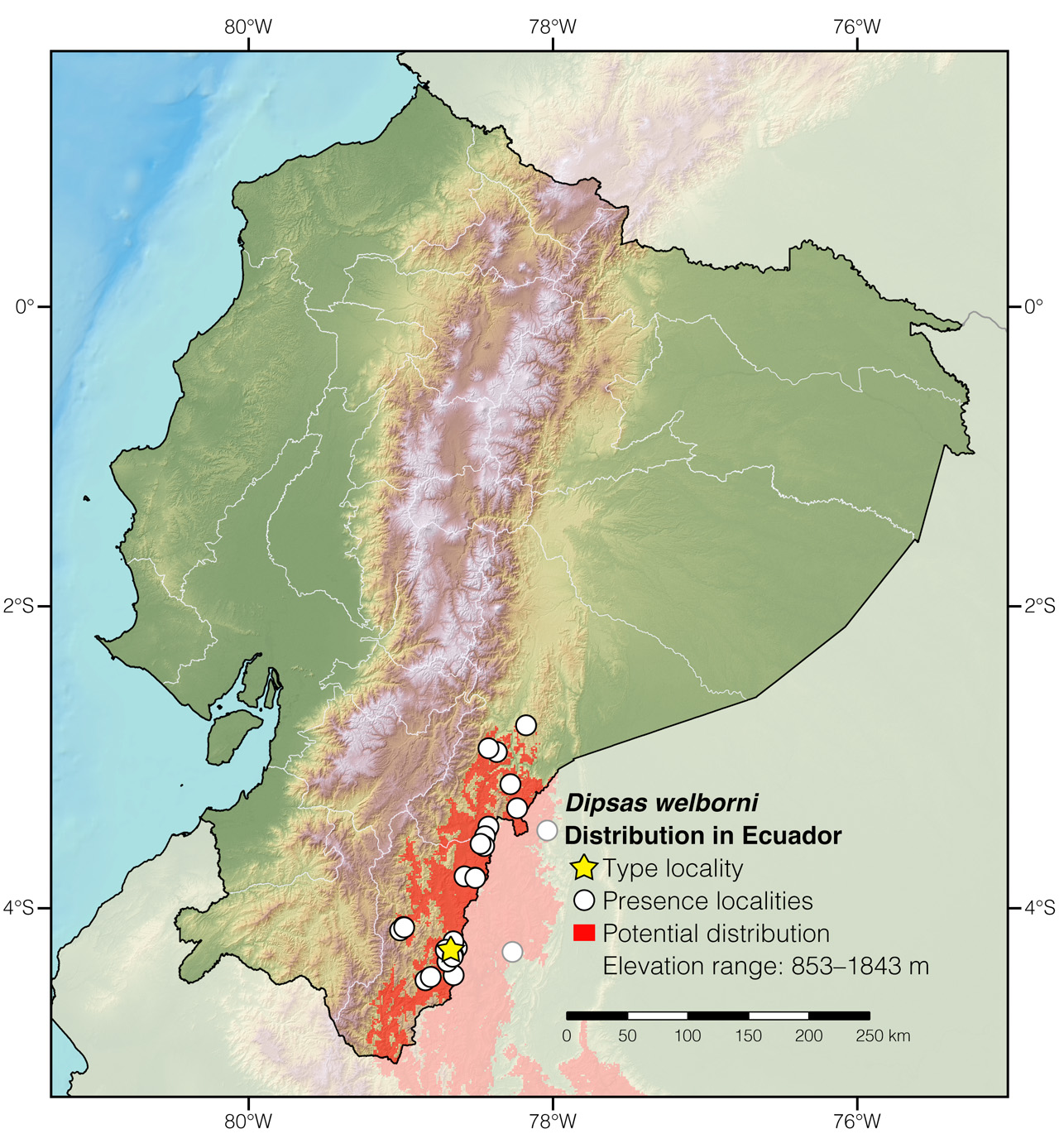

Distribution: Dipsas welborni is native to the Amazonian foothills of the Andes, particularly along the Cordillera del Cóndor, in Ecuador (Fig. 2) and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Dipsas welborni in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Vía Miazi–Nuevo Paraiso, Zamora Chinchipe province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Dipsas comes from the Greek dipsa (=thirst)6 and probably refers to the fact that the bite of these snakes was believed to cause intense thirst. The specific epithet welborni honors David Welborn, a lifelong champion of ecosystem and species conservation who supports and serves on several nonprofit boards dedicated to the environment.1

See it in the wild: Welborn’s Snail-eating Snakes can be seen at a rate of about once every few nights, especially after a rainy day in forested areas throughout the Cordillera del Cóndor. The locality having the greatest number of recent observations of Dipsas welborni is Reserva Natural Maycu, where the snakes are most easily recorded by scanning understory vegetation along forest trails at night.

Author and photographer: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Welborn’s Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas welborni). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ALIS2563

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Batista A (2023) A consolidated phylogeny of snail-eating snakes (Serpentes, Dipsadini), with the description of five new species from Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama. ZooKeys 1143: 1–49. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.1143.93601

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- De Oliveira L, Jared C, da Costa Prudente AL, Zaher H, Antoniazzi MM (2008) Oral glands in dipsadine “goo-eater” snakes: morphology and histochemistry of the infralabial glands in Atractus reticulatus, Dipsas indica, and Sibynomorphus mikanii. Toxicon 51: 898–913. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.12.021

- Cadle JE, Myers CW (2003) Systematics of snakes referred to Dipsas variegata in Panama and Western South America, with revalidation of two species and notes on defensive behaviors in the Dipsadini (Colubridae). American Museum Novitates 3409: 1–47.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dipsas welborni in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cascadas Coloradas | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad Shuar Kukunk | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cordillera de Cutucú | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | El Zarza, zona de amortiguamiento | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Limón, 6.6 km N of | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Reserva Biológica El Quimi | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Valle del Río Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Warintza | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alrededores de Ciudad Perdida | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alto Machinaza | Almendáriz et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Campamento Fruta del Norte | Almendáriz et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Concesión ECSA | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Cordillera del Cóndor | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Maycu Reserve* | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Miazi | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Nangaritza | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Podocarpus | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Quimi | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Sendero Higuerones | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Sendero junto al Río Nangaritza | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Shaime | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tepuy Las Orquídeas | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Vía Miazi–Nuevo Paraiso | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Alto Río Santiago | Vera-Pérez 2020 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami, 1 km W of | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Perú | San Martín | Área de Conservación Regional Cordillera Escalera | Photo by Angel Chujutalli |

| Perú | San Martín | La Banda de Shilcayo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | San Martín | Pampa Hermosa, 10 km W of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | San Martín | Salto de la Bruja | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | San Martín | Tarapoto, 5 km NE of | Photo by Cristian Torica |