Published May 12, 2018. Updated April 11, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Temporal Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas temporalis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Dipsas temporalis

English common name: Temporal Snail-eating Snake.

Spanish common name: Caracolera temporal.

Recognition: ♂♂ 69.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=44.7 cm. ♀♀ 64.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=41.6 cm..1,2 Dipsas temporalis can be identified by having a pointed head and a light brown dorsum with 26–39 white-edged dark brown blotches (Fig. 1).1,3 The dorsal aspect of the head is uniformly dark reddish-brown, becoming dingy white towards labials.1,3 This species differs from D. gracilis by having dark brown elliptical blotches (instead of complete black bands) on the posterior half of the body.1,3,4

Figure 1: Individuals of Dipsas temporalis from Durango, Esmeraldas province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Dipsas temporalis is a nocturnal snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed lowland rainforests, occurring in lower densities, or not at all, in forest-edge situations.5 Temporal Snail-Eaters are active at night, especially if it is raining or drizzling.4,5 Their movements through the foliage are slow, graceful, and generally occur during the first hours of the night on the lower (0.3–4.5 m above the ground) forest stratum.4,5 During the daytime, they sleep in leaf-litter or coiled inside bromeliads 1.2–3 m above the ground.4,5 Nothing is known about the diet in this species, but snakes of the genus Dipsas in general feed almost exclusively on snails and slugs. Although some snail-eaters produce saliva that is toxic to mollusks,6 these snakes are considered harmless to humans. They never attempt to bite, resorting instead to musking and flattening the body while expanding the head to simulate a triangular shape.4,7

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..8 Dipsas temporalis is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, especially in areas that have not been heavily affected by deforestation, like the Colombian Pacific coast, and it is unlikely to be declining fast enough to qualify for a more threatened category.8 The most important threat for the long-term survival of this strictly forest-dwelling snake is the loss of habitat due to large-scale deforestation.8

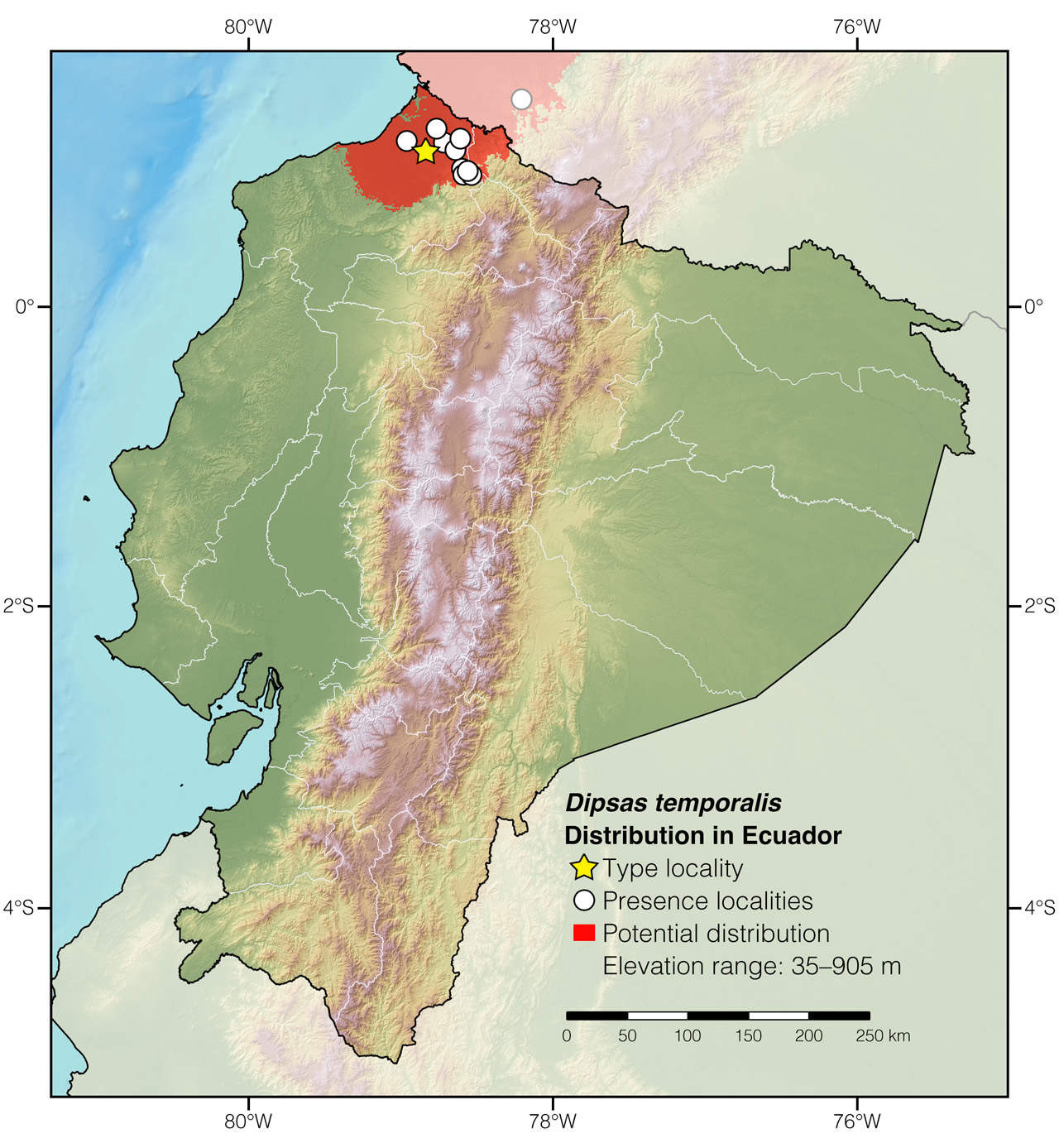

Distribution: Dipsas temporalis is native to the Chocó region, from eastern Panamá, through western Colombia, to extreme northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Dipsas temporalis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Esmeraldas province, Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Dipsas comes from the Greek dipsa (=thirst)9 and probably refers to the fact that the bite of these snakes was believed to cause intense thirst. The specific epithet temporalis calls attention to the unusual fact that, in some individuals, the temporal scale is in contact with the eye.4.

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Temporal Snail-eating Snakes are encountered frequently only in pristine rainforests near the Colombian border, an area currently considered unsafe for travelers. The areas having the greatest number of recent observations are the immediate environs the towns of Durango and Alto Tambo.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Temporal Snail-eating Snake (Dipsas temporalis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/HMBY8129

Literature cited:

- Ray JM, Sánchez-Martínez P, Batista A, Mulcahy DG, Sheehy CM, Smith EN, Pyron RA, Arteaga A (2023) A new species of Dipsas (Serpentes, Dipsadidae) from central Panama. ZooKeys 1145: 131–167. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.1145.96616

- Arteaga A, Batista A (2023) A consolidated phylogeny of snail-eating snakes (Serpentes, Dipsadini), with the description of five new species from Colombia, Ecuador, and Panama. ZooKeys 1143: 1–49. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.1143.93601

- Peters JA (1960) The snakes of the subfamily Dipsadinae. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, Univesity of Michigan 114: 1–224.

- Harvey MB (2008) New and poorly known Dipsas (Serpentes: Colubridae) from Northern South America. Herpetologica 64: 422–451. DOI: 10.1655/07-068R1.1

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- De Oliveira L, Jared C, da Costa Prudente AL, Zaher H, Antoniazzi MM (2008) Oral glands in dipsadine “goo-eater” snakes: morphology and histochemistry of the infralabial glands in Atractus reticulatus, Dipsas indica, and Sibynomorphus mikanii. Toxicon 51: 898–913. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2007.12.021

- Cadle JE, Myers CW (2003) Systematics of snakes referred to Dipsas variegata in Panama and Western South America, with revalidation of two species and notes on defensive behaviors in the Dipsadini (Colubridae). American Museum Novitates 3409: 1–47.

- Ibáñez R, Jaramillo C, Velasco J, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Bolívar W (2015) Dipsas temporalis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T203503A2766570.en

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Dipsas temporalis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Antioquia | Mutatá | Sheehy 2012 |

| Colombia | Antioquia | San Ignacio | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Antioquia | Sector Pantanos | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Cauca | San Cipriano | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Alto del Buey, N slope | Harvey 2008 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Camino de Yupe | Harvey 2008 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Cerro Iró | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Condoto | Harvey 2008 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Las Bocas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Chocó | Pacurita | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Río Bebarama | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Chocó | Río Tamaná | Harvey 2008 |

| Colombia | Chocó | Vereda Salero | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Córdoba | Parque Natural Nacional Paramillo | Pérez-Torres et al. 2016 |

| Colombia | Nariño | El Charco | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Reserva Natural El Pangán | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Risaralda | Alto Amurrapá | Bonilla and Moya 2021 |

| Colombia | Risaralda | Pueblo Rico | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | El Danubio | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | Quebrada la Batea | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | Río Bravo | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Valle del Cauca | Sector La Cueva | Vera-Pérez 2019 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Alto Tambo–Río Negro | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Alto Tambo, 4 km W of | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Borbón | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Durango | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Durango, 4 km N of | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Esmeraldas* | Werner 1909 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Junto al Río Chuchubí | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Lita,16 km W of | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma Lodge | Arteaga et al. 2018 |

| Panama | Comarca Emberá-Wounaan | Serranía de Jingurudo | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Panama | Darién | Cerro Bailarín | Ray et al. 2023 |

| Panama | Darién | Rancho Frío Field Station | Arteaga & Batista 2023 |

| Panama | Darién | Ridge between Río Jaqué and Río Imamadó | Cadle and Myers 2003 |

| Panama | Darién | Serranía de Pirre | Harvey 2008 |