Published May 9, 2021. Updated March 7, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Brown Whipsnake (Chironius fuscus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Chironius fuscus

English common names: Brown Whipsnake, Brown Sipo, Olive Whipsnake, Red-fronted Tree Snake.

Spanish common name: Serpiente látigo marrón, serpiente látigo oliva (Ecuador); cazadora, juetiadora, lomo de machete (Colombia); serpiente de olivo, sipo marrón (Peru); cuaima machete, cuaima gallo, machete, verdegallo (Venezuela).

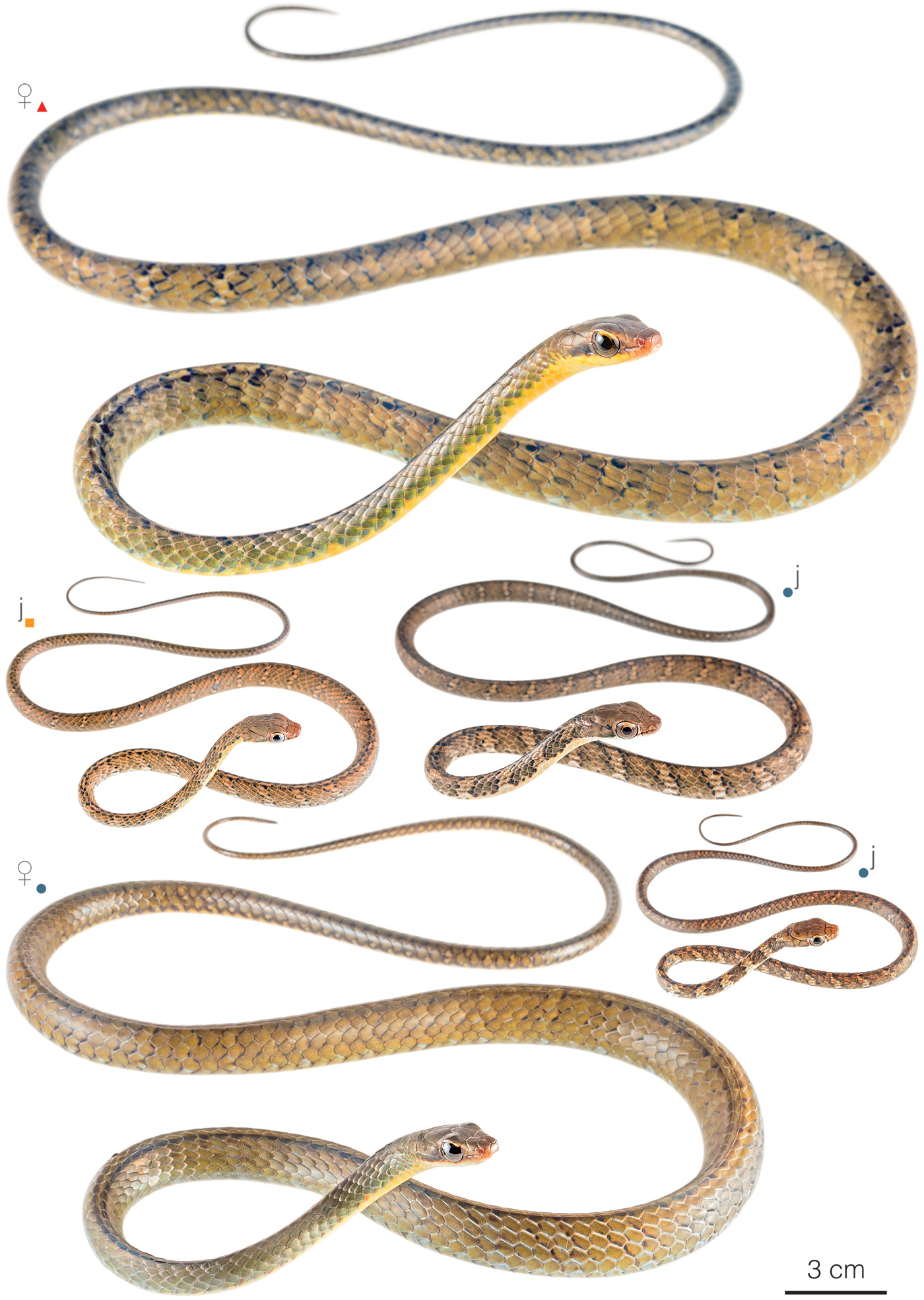

Recognition: ♂♂ 159.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=109.5 cm. ♀♀ 151.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1,2 Chironius fuscus can be identified by having 10 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body, keels on either side of the vertebral line, and a olivaceous or brownish dorsal coloration (Fig. 1).1–4 The keels may be darkened, giving the appearance of two dark stripes.1 The venter is cream or yellowish, becoming darker towards the tail.1,4 Juveniles are olive to brown with light transverse bands, which tend to disappear when the animal reaches a body length of 35–40 cm.1,3 This species differs from C. exoletus and C. multiventris by having 10 rows of dorsal scales at mid-body.1 From the adults of C. scurrula, it differs by having a brown, instead of red or black dorsum.1,5 From C. leucometapus, it differs by having a brown, instead of green, dorsum and by having a postocular stripe.6

Figure 1: Individuals of Chironius fuscus from Ecuador: Yasuní Scientific Station, Orellana province (); Huella Verde Lodge, Pastaza province (); Nangaritza, Zamora Chinchipe province (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Chironius fuscus is a common diurnal and semi-arboreal snake that inhabits old-growth to heavily disturbed evergreen forests, which can be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.3,5,7 The species also occurs in human-modified environments such as grasslands and plantations.8,9 Brown Whipsnakes are almost exclusively active during warm days, but there are records of individuals foraging at night near ponds.10 Most of their active time is spent foraging at ground level or moving on vegetation 0.4–2 m above the ground.2,10,11 They can also be seen crossing roads and trails, resting/basking on trees or at ground level, and swimming across bodies of water, including major Amazonian rivers.5,9,12 Around 6:00–7:00 pm, these snakes begin to look for a perch to sleep,13 such as branches, leaves, and ferns near bodies of water at 0.2–5 m above the ground.3,9,11 An individual can use the same roosting place repeatedly.10 If disturbed during their sleep, Brown Whipsnakes will usually drop to the ground, quickly ascending to the nearest vegetation.3

Brown Whipsnakes are active hunters having an aglyphous dentition, meaning their teeth lack specialized grooves to deliver venom.1,2 Therefore, they ingest prey quickly to avoid them from escaping.1,2 Their diet consists mainly of anurans (including Boana boans,14 Leptodactylus petersii, L. mystaceus, Osteocephalus taurinus,9 and Trachycephalus macrotis),15 but also includes salamanders,15 lizards (anoles,16 whiptails,17 and geckos such as Gonatodes humeralis),15 birds, and mice.16 There are records of Laughing Falcons (Herpetotheres cachinnans) preying upon individuals of this species.12 The main defense mechanism of Brown Whipsnakes is to flee quickly, although they can also inflate the neck and open the mouth aggressively to appear bigger and intimidating; if this does not work, they can also strike.5,16 Males attain sexual maturity when they reach ~53 cm in total length; females at ~57.6 cm.18 The breeding season in this species seems to be continuous, since females having oviductal eggs (between 3 and 8) have been recorded throughout the year.17,18

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..19–21 Chironius fuscus is included in this category given the species’ wide distribution, occurrence in protected areas (including all major national parks in Amazonian Ecuador), and presumed stable populations.19 However, the abundance of this species is thought to be diminishing in areas affected by deforestation19 and vehicular traffic.22,23

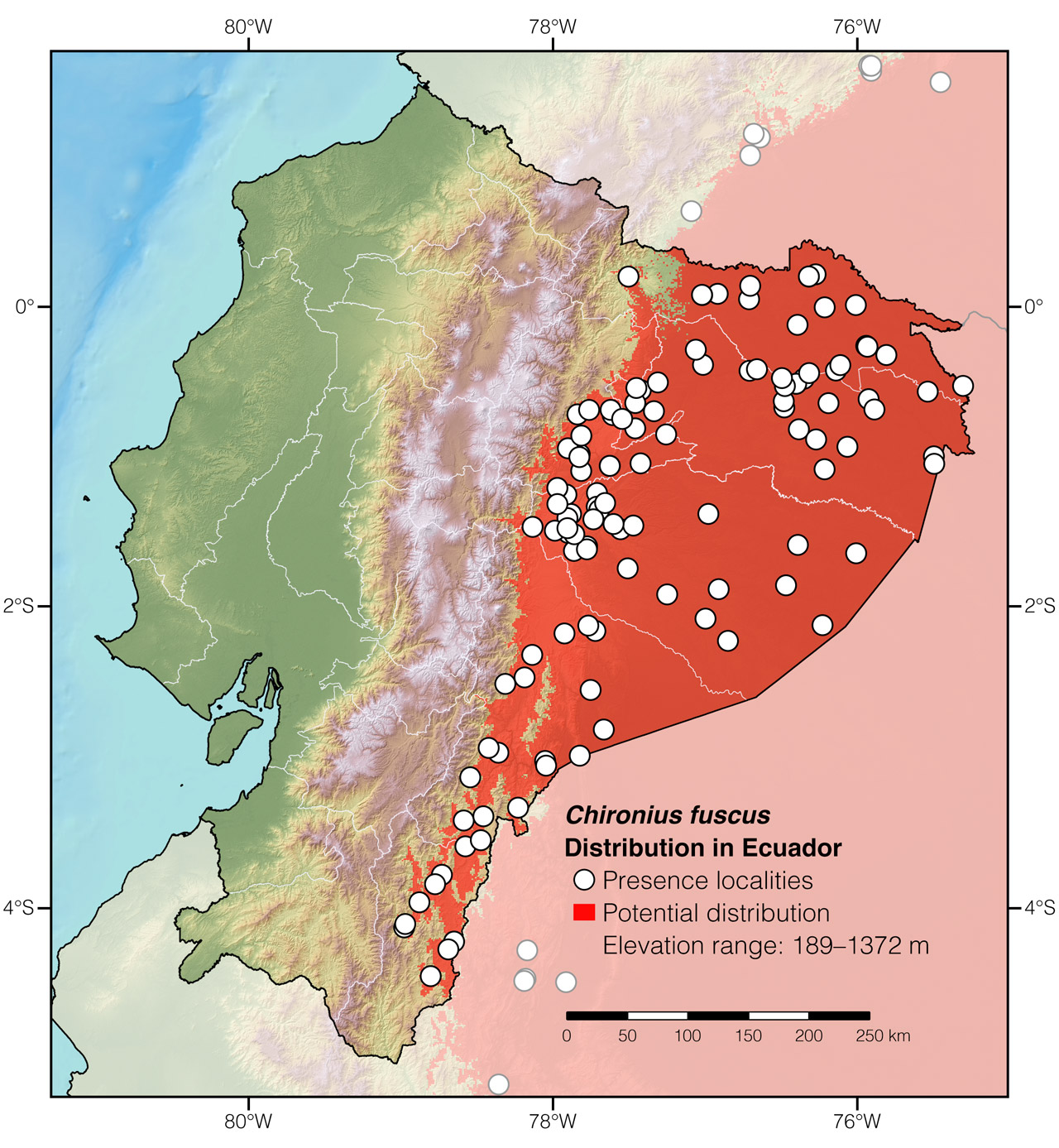

Distribution: Chironius fuscus is widely distributed throughout the Amazon in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), French Guiana, Guyana, Peru, Suriname and Venezuela, as well as in the Atlantic Forest biome of Brazil. The species has an estimated total range size of 2,139,501 km2.24

Figure 2: Distribution of Chironius fuscus in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Chironius was coined by Leopold Fitzinger in 1826, but likely originated in 1790 with Blasius Merrem, who used the common name “Chiron’s Natter” for Linnaeus’ Coluber carinatus.25 In Greek mythology, Chiron was a centaur reputed for his healing abilities. Likewise, in ancient Greek civilization, sick people hoping for a cure flocked to temples where sacred snakes were carefully tended and presented to the sufferers. Therefore, Chironius likely refers to the healing power of snakes, a belief that lies at the foundation of medicine and crosses many cultures worldwide.26,27 The specific epithet fuscus is a Latin word meaning “dark” or “swarthy.”28 It refers to the dark coloration of the body and the postocular dark stripe present in some individuals.

See it in the wild: Brown Whipsnakes are frequently encountered in forested areas throughout their area of distribution in Ecuador. The localities having the greatest number of observations are Yasuní Scientific Station, Maycu Reserve, and Tamandúa Reserve. The snakes are most easily spotted when they are sleeping on vegetation along water bodies at night, or moving on pastures during sunny days.

Special thanks to Mami Okura for symbolically adopting the Brown Whipsnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Juan Acosta-Ortiz,aAffiliation: Semillero de Investigación BioHerp, Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. Juan Bobadilla-Molina,aAffiliation: Semillero de Investigación BioHerp, Universidad de los Llanos, Villavicencio, Colombia. and Andrés F. Aponte-GutiérrezbAffiliation: Grupo de Biodiversidad y Recursos Genéticos, Instituto de Genética, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.,cAffiliation: Fundación Biodiversa Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia.

Editor: Alejandro ArteagadAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Acosta-Ortiz J, Bobadilla-Molina J, Aponte-Gutiérrez A (2024) Brown Whipsnake (Chironius fuscus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/RZHK7496

Literature cited:

- Dixon JR, Wiest Jr JA, Cei JM (1993) Revision of the Neotropical snake genus Chironius Fitzinger (Serpentes, Colubridae). Museo Regionale di Scienze Naturali di Torino, Torino, 280 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- de Fraga R, Lima AP, da Costa Prudente AL, Magnusson WE (2013) Guia de cobras da região de Manaus - Amazônia Central. Editopa Inpa, Manaus, 303 pp.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Koch C, Valencia JH, Venegas PJ, Echevarría LY (2019) Morphology and distribution of the South American snake Chironius leucometapus (Serpentes: Colubridae). Phyllomedusa 18: 241–254. DOI: 10.11606/issn.2316-9079.v18i2p241-254

- Cunha OR, Nascimento FP (1993) Ofídios da Amazônia. As cobras da região leste do Pará. Papéis Avulsos Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 40: 9–87.

- Cortes-Ávila L, Toledo JJ (2013) Estudio de la diversidad de serpientes en áreas de bosque perturbado y pastizal en San Vicente del Caguán (Caquetá), Colombia. Actualidades Biológicas 35: 185–197.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Hartmann PA (2005) História natural e ecologia de duas taxocenoses de serpentes na Mata Atlântica. PhD thesis, Rio Claro, Universidade Estadual Paulista, 117 pp.

- Field notes of Juan Sebastián Bobadilla-Molina.

- Field notes of Andrés Felipe Aponte-Gutiérrez.

- Field notes of Juan Manuel Acosta-Ortiz.

- Arrivillaga C, Levac A (2019) A failed predation attempt on a Rusty Treefrog, Hypsiboas boans (Anura: Hylidae), by an Olive Whipsnake, Chironius fuscus (Squamata: Colubridae), in southeastern Perú. IRCF Reptiles & Amphibians 26: 111–112.

- Roberto IJ, Ramos Souza A (2020) Review of prey items recorded for snakes of the genus Chironius (Squamata, Colubridae), including the first record of Osteocephalus as prey. Herpetology Notes 13: 1–5.

- Beebe W (1946) Field notes on the snakes of Kartabo, British Guiana, and Caripito, Venezuela. Zoologica 31: 11–52.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Nascimento LP, Mendes Siqueira D, dos Santos-Costa MC (2013) Diet, reproduction, and sexual dimorphism in the Vine Snake, Chironius fuscus (Serpentes: Colubridae), from Brazilian Amazonia. South American Journal of Herpetology 8: 168–174. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-13-00017.1

- Caicedo J, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Rivas G, Nogueira C, Gonzales L, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Catenazzi A, Gagliardi G, Hoogmoed M, Schargel W (2019) Chironius fuscus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T44580103A44580112.en

- Carrillo E, Aldás A, Altamirano M, Ayala F, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Endara A, Márquez C, Morales M, Nogales F, Salvador P, Torres ML, Valencia J, Villamarín F, Yánez-Muñoz M, Zárate P (2005) Lista roja de los reptiles del Ecuador. Fundación Novum Millenium, Quito, 46 pp.

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Hartmann PA, Hartmann MT, Martins M (2011) Snake road mortality in a protected area in the Atlantic Forest of southeastern Brazil. South American Journal of Herpetology 36: 35–42.

- Sosa R, Schalk CM (2016) Seasonal activity and species habitat guilds influence road-kill patterns of neotropical snakes. Tropical Conservation Science 9: 1–12. DOI: 10.1177/1940082916679662

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Merrem B (1790) Beitrage zur Naturgeschichte. Duisburg um Lemgo, Berlin, 141 pp.

- Nayernouri T (2010) Asclepius, caduceus, and simurgh as medical symbols. Archives of Iranian Medicine 13: 61–68.

- Güner E, Şeker KG, Güner Ş (2019) Why is the medical symbol a snake? Istanbul Medical Journal 20: 172–175. DOI: 10.4274/imj.galenos.2018.65902

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Chironius fuscus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Caserío Los Ángeles | Caicedo Portilla 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Finca de Erley Navas | Caicedo Portilla 2023 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Las Dalias Nature and Ecotourism Reserve | Photo by John Himes |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Quebrada Las Verdes | Caicedo Portilla 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Finca Mariposa | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mocoa | Cárdenas Hincapié & Lozano Bernal 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Reserva Amaru | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Guamués | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loreto | San José de Payamino | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad Kiim | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad Shuar Kunkuk | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | El Pescado | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Kushapucus | MZUA.RE.0196; examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Mirador de la Virgen | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Nuevo Israel | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Quebrada Namakunts | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Rio Cusuime | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Napinaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Juan Bosco | MZUA.RE.0241; examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Santa Teresa | USNM 283946; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Sucúa | Fugler & Walls 1978 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Tundayme | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Wisui | Chaparro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ahuano | MCZ 173828; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cotundo, 12 km NW of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno Lodge | Photo by Sandro Aguinda |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | MCZ 173828; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Narupa Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pitalala, meseta | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Misahuallí | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Napo, YasunÍ National Park | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Francisco | Fugler & Walls 1978 |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Juan de Muyuna | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Juan de Piatua | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Vía Guamaní–Hollín | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco, lower trails | Photo by Dr. Dark |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Whitworth & Beirne 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zoo el Arca | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Ávila Viejo | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Chiru Isla | Paulina Romero, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Sinchichikta | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Cotapino | Fugler & Walls 1978 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Laguna Jatuncocha | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Laguna Zancudo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | USNM 287927; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Chonta | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Petrolero Nambi | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní | María Jose Quiroz, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tambococha | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Loreto-Río Hollín | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 40 | Photo by Morley Read |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro, km 90 | Photo by Morley Read |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Wati | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Balsaura | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Río Bobonaza | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento K10 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campamento Villano B | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | Fugler & Walls 1978 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Centro Ecológico Zanja Arajuno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Pablo López de Oglán Alto | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Diez de Agosto | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Heimatlos Lodge | Photo by Ferhat Gundogdu |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Huella Verde Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Lorocachi | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Oglán | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pavacachi | USNM 237010; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pucayacu (Río Pucayacu) | USNM 237005; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | USNM 205035; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bobonaza | Photo by Andreas Kay |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | USNM 237014; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Curaray | USNM 237010; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | USNM 237012; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Oglán | USNM 237007; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Talin | USNM 237009; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sacha Yaku | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | San Juan de Piatúa | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tamandúa Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Aguarico Protective Forest | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Boca del Río Cuyabeno | USNM 237003; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comunidad Siugue | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Yánez & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno, 18 km N of | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Embarcadero La Selva Lodge | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE en Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Amazon Ecolodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | KU 300711; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pacayacu | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañacocha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Playas del Cuyabeno | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Libre | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Putumayo | OMNH 36519.0; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Singüe | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | Photo by Charlie Vogt |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia, 3 km W of | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Zábalo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Bombuscaro | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Ciudad Perdida | Darwin Núñez, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Copalinga | Reeves et al. (unpublished) |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Cumbaratza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Maycu Nature Reserve | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Zamora | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Tepuy Las Orquídeas | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Valle del Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aguaruna village | MVZ 163254; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Cabeceras del Río Cenepa | MVZ 163253; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Chiriaco | Dixon et al. 1993 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Comunidad Nativa Copallin | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Perú | Amazonas | El Cenepa | USNM 316584; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Río Santiago | USNM 566712; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Vicinity of La Poza | MVZ 175312; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Aguas Negras | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |