Published December 14, 2020. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Viperidae | Bothrocophias campbelli

English common names: Ecuadorian Toadhead, Ecuadorian Toad-headed Pitviper, Campbell’s Toadhead Viper, Campbell’s Lancehead.

Spanish common names: Curruncha, equis pachona, boca de sapo, víbora de Campbell.

Recognition: ♂♂ 98 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 123 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail.. The Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli) can be identified from other snakes in its area of distribution by having a triangular-shaped head, heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils, an upturned snout, and prominent knoblike keels on the dorsal scales.1,2 Adults have a series of faint trapezoidal blotches on a brownish dorsum. In juveniles, the dorsal pattern is more contrasting and the tail is bright reddish brown.1 In Ecuador, the most similar species that may be found living alongside B. campbelli is B. asper, which lacks an upturned snout3 and has comparatively much bigger eyes than B. campbelli.

Figure 1: Individuals of Bothrocophias campbelli from Mindo, Pichincha province (); Milpe Bird Sanctuary, Pichincha province (); Manduriacu Reserve, Imbabura province (); and Buenaventura Reserve, El Oro province (); Ecuador. a=adult, sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: UncommonUnlikely to be seen more than once every few months.. Bothrocophias campbelli is a cryptozoic (preferring moist, shaded microhabitats) snake that inhabits old-growth to moderately disturbed evergreen montane forests, cloud forests, and forest borders, usually in areas having abundant leaf-litter.1 The species prefers forests where the mean annual temperature is between 17.01° C and 22.71° C.4 Throughout the day, Ecuadorian Toadheads typically remain inactive and coiled on the forest floor, usually among herbaceous vegetation, or sheltered below leaf-litter, timber, and logs.1,5 Occasionally, they are active during the daytime, waiting in ambush or moving at ground level.5 At night, most individuals of B. campbelli sit-and-wait on soil or among leaf-litter, but may as well be seen moving on the forest floor.5

Ecuadorian Toad-headed Pivipers are ambush predators, and they usually “bite and hold” their prey.3 Their diet includes rodents,3,6 lizards (such as Alopoglossus viridiceps5 and species of the genus Riama),3 snakes (Urotheca lateristriga7 and unidentified Atractus groundsnakes),8 and caecilians (Caecilia buckleyi).9 Ecuadorian Toadheads rely on their camouflage as a primary defense mechanism. When threatened, some individuals vigorously wiggle their tail against the leaf-litter whereas others just readily bite if attacked or harassed.1,3 Members of this species are preyed upon by the snake Clelia equatoriana.1

Bothrocophias campbelli is a venomous species (LD50The median lethal dose (LD50) is a measure of venom strength. It is the minium dosage of venom that will lead to the deaths of 50% of the tested population. 7.5 mg/kg).10 Based on laboratory tests on mice, the venom of this species has low coagulant and hemorrhagic effects but strong myotoxic activity,10 which causes severe death of tissues and cells, and presumably also death. In the single reported case of human envenomation,3 the victim experienced intense pain and swelling.3

Bothrocophias campbelli is a viviparous species, meaning the females bring forth live young that have developed inside the body of the parent. In Mindo, Ecuador, one female gave birth to 21 young that measured 13.4–16.2 cm in total length.11 Under human care, individuals can live up to ~14 years,3 and probably much longer.

Conservation: Vulnerable Considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the mid-term future..12 Bothrocophias campbelli is listed in this category because its geographic range is greater than 5,000 km2 but smaller than 20,000 km2, even when accounting for lost habitat. Thus, the species does not meet the criteria for qualifying as Endangered. In Ecuador, B. campbelli occurs over an estimated 13,940 km2 area where only ~50% of the habitat is forested.13 The most important threat to the long-term survival of the species is habitat destruction mostly due to large-scale mining (especially in Imbabura province)14 and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Other causes of mortality for individuals of this species are vehicle traffic and direct killing.5

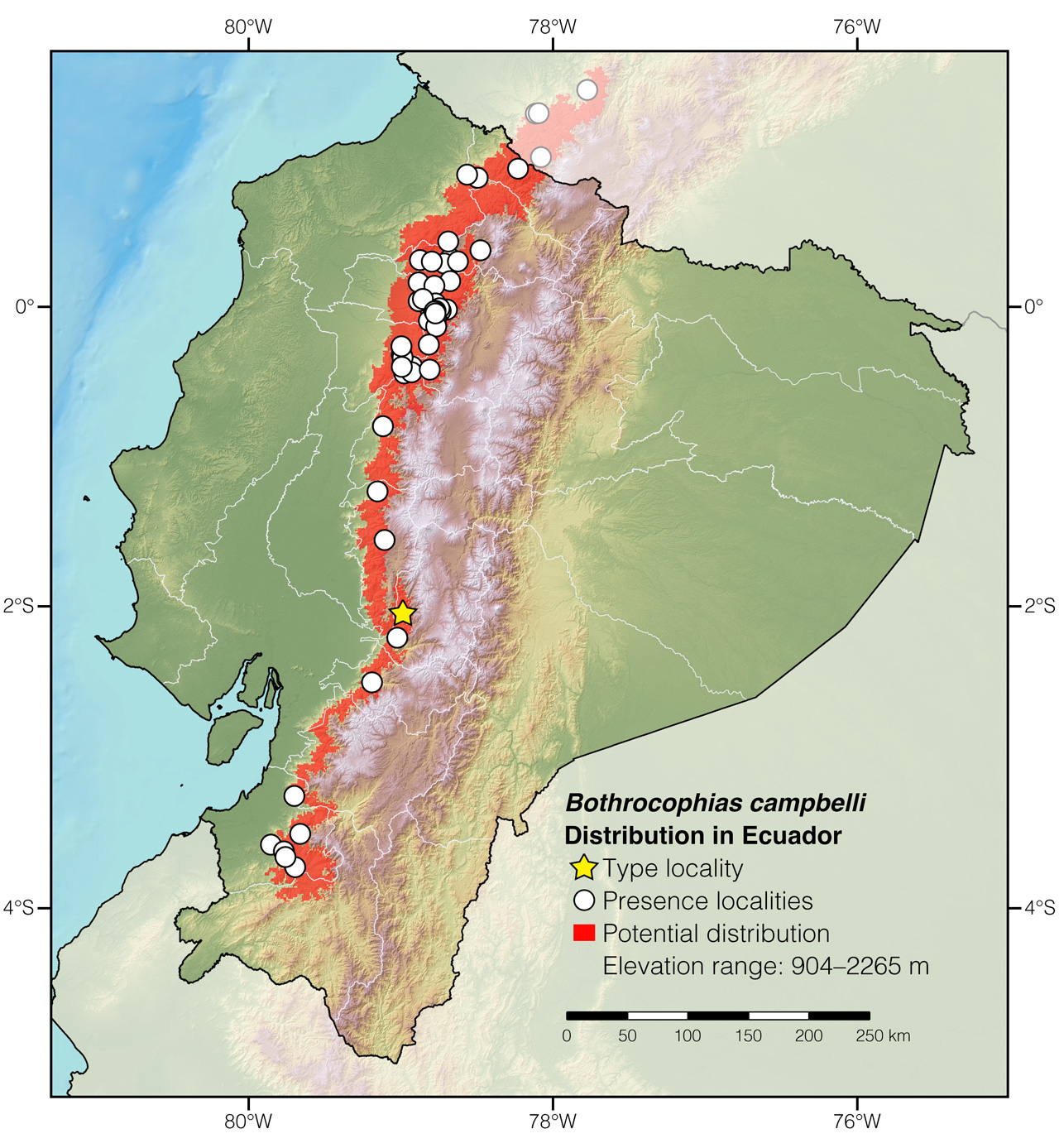

Distribution: Bothrocophias campbelli is native to the Pacific slopes of the Andes in Colombia and Ecuador. In Ecuador, the species occurs over an estimated 13,940 km2 area at elevations between 725 and 2265 m (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Bothrocophias campbelli in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Bothrocophias, which is derived from the Greek words bothros (meaning “pit”) and kophias (meaning “snake”), refers to the heat-sensing pits between the eyes and nostrils.2 The specific epithet campbelli honors Jonathan Campbell, one of the world’s most widely acclaimed herpetologists.1

See it in the wild: Ecuadorian Toad-headed Pitvipers can be located with ~1–3% certainty in forested areas throughout the species’ area of distribution. Some of the best localities to find vipers of this species in Ecuador are: Séptimo Paraíso Lodge, Hacienda San Vicente, Buenaventura Biological Reserve, and Manduriacu Reserve. The vipers may be located by walking along forest trails during the first few hours after sunset, especially after a warm day.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Leodán Aguilar for finding two of the individuals of Bothrocophias campbelli photographed in this account.

Special thanks to Wolfgang Wüster for symbolically adopting the Ecuadorian Toadhead and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Editor: Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Laboratorio de Biología Evolutiva, Universidad San Francisco de Quito (USFQ), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: Galapagos Science Center, Galápagos, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Centro de Investigación de la Biodiversidad y Cambio Climático, Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Jorge ValenciaeAffiliation: Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés (FHGO), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di DoménicogAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2020) Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZBMA5522

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Vaca-Guerrero JE (2012) Biogeografía del género Bothrocophias (Serpentes: Viperidae: Crotalinae), mediante modelamientos de nicho ecológico. BSc Thesis, Universidad Central del Ecuador, 116 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Freire A, Kuch U (2000) Bothrops campbelli (Campbell’s Lancehead). Diet and reproduction. Herpetological Review 31: 45.

- Rojas-Rivera A, Castillo K, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas PDA (2013) Bothrocophias campbelli (Campbell’s Toad-headed Pit-viper, Víbora Boca de Sapo de Campbell). Diet/ophiophagy. Herpetological Review 44: 518.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Borja MO, Proaño D, Touzet JM (2006) Distribution and natural history of the Ecuadorian toad-headed pitvipers of the genus Bothrocophias. Herpetozoa 19: 17–26.

- Zuffi MAL (2004) Bothrops campbelli (Campbell’s Lancehead). Diet. Herpetological Review 35: 57–58.

- Salazar-Valenzuela D, Mora-Obando D, Fernández ML, Loaiza-Lange A, Gibbs HL, Lomonte B (2014) Proteomic and toxicological profiling of the venom of Bothrocophias campbelli, a pitviper species from Ecuador and Colombia. Toxicon 90: 15–25. DOI: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2014.07.012

- Valencia JH, Garzón K, Betancourt-Yépez R (2008) Notes on the reproduction of the Ecuadorian toad-headed pitviper Bothrocophias campbelli (Freire-Lascano 1991). Herpetozoa 21: 95–96.

- Caicedo JR, Calderón M, Ines Hladki A, Mendoza-Quijano F, Ramírez Pinilla M, Renjifo J, Urbina N (2019) Bothrocophias campbelli. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T15203980A15203988.en

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Jorge Valencia, pers. comm.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Bothrocophias campbelli in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Reserva Natural Río Ñambí 1 | Castro et al. 2005 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Reserva Natural Río Ñambí 2 | Rojas-Rivera et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Cañar | Hidroeléctrica Ocaña | MZUA.RE.0135 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Guagual | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Chimborazo | Sacramento | Freire-Lascano 1991 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Galápagos | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Guasaganda | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Juntas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Las Pampas | Schätti & Kramer 1993 |

| Ecuador | Cotopaxi | Palo Quemado | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | El Progreso | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | La Chonta | Gutberlet & Campbell 2001 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Lote Guzmán | This work |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Reserva Buenaventura | This work |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | El Cristal | Pablo Loaiza, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Río Negro Chico | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Chalguayacu, north of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Chontal Alto | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Intag | Orcés 1948 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Reserva Manduriacu | This work |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Río Los Cedros | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Santa Rosa de Intag | Nelson Ruiz |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Alluriquín | Jorge Valencia, pers. comm. |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bellavista Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Birdwatcher’s House | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Pachijal | Photo by Fernanda Patiño |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cascadas de Mindo | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Finca Elenita | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Gavilán Orongo | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Las Tolas | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mashpi Reserve | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Milpe Bird Sanctuary | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Garden Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Mindo Lindo Lodge | Video by Heike Brieschke |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Pacto | Gutberlet & Campbell 2001 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Primero de Mayo, north of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Las Gralarias | Photo by Tim Krynak |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Las Tangaras | Photo by Peter Detwiler |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Un Poco de Chocó | Nicole Buttner |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Río Cinto | Photo by Lisa Brunetti |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Sachatamia Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Saragoza–Río Cinto | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Séptimo Paraíso Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Tandapi | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Yellow House Lodge | This work |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Alluriquín, above | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2006 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | La Florida, above | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Reserva Guajalito (Jocotoco) | MECN 7677 |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Río Lelia | iNaturalist |