Published November 11, 2021. Updated December 12, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Green-headed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus viridiceps)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Alopoglossidae | Alopoglossus viridiceps

English common name: Green-headed Shade-Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija sombría cabeciverde, lagartija de sombra de cabeza verde.

Recognition: ♂♂ 17.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.4 cm. ♀♀ 15.8 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=5.7 cm..1 The Green-headed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus viridiceps) is a small, brownish lizard with a light mid-dorsal stripe, and a bright green head coloration.1 This species can be distinguished from other lizards in western Ecuador by having strongly keeled and overlapping scales on both the dorsum and flanks2 and by lacking occipital and postparietal scales. Alopoglossus viridiceps could be confused with A. harrisi, from which it differs by having a green head, 29–32 dorsal scales in a transverse row at mid-body (instead of 16–24), and by presenting a clear line that goes from the corner of the mouth to the shoulder.1 However, these two species are not known to co-occur. In the cloud forests of northwestern Ecuador, A. viridiceps occurs alongside Pholidobolus vertebralis, a lizard with a similar coloration that differs by having the scales on the flanks rounded and finely wrinkled.3

Figure 1: Individuals of Alopoglossus viridiceps from Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve, Imbabura province, Ecuador. sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Alopoglossus viridiceps is a locally frequent lizard species that occurs in areas of old growth to moderately disturbed evergreen montane forest and cloud forest,4 especially in clearings where the sunlight reaches the ground.3,5 The species is also found in disturbed areas such as along roads and sugarcane plantations.6 Green-headed Shade-Lizards are diurnal and they are most active between 9:30 am and 11:30 am during sunny days.1 Individuals forage among leaf-litter, soil, or on low herbaceous vegetation.5,6 When not active, they hide under rocks and logs.6 In the presence of a disturbance, individuals usually quickly retreat under leaf-litter; if captured, they may shed the tail or bite.6 There is an unpublished observation of an Ecuadorian Toadhead (Bothrocophias campbelli) preying upon an individual of this species.6 Nothing is known about the reproductive habits of this lizard, although other Alopoglossus lay two eggs per clutch.7

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations.. Alopoglossus viridiceps is proposed to be included in this category following IUCN criteria8 because although the species’ extent of occurrence is estimated to be less than 2,000 km2, the majority (~68%) of this area still holds native forest. Also, nearly half (Appendix 1) of the localities where A. viridiceps occurs are privately protected. Thus, the species is here considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats. However, some populations are likely to be declining due to deforestation by logging and large-scale mining,9 especially in the provinces Esmeraldas and Imbabura, where the species has only been recorded in four localities.

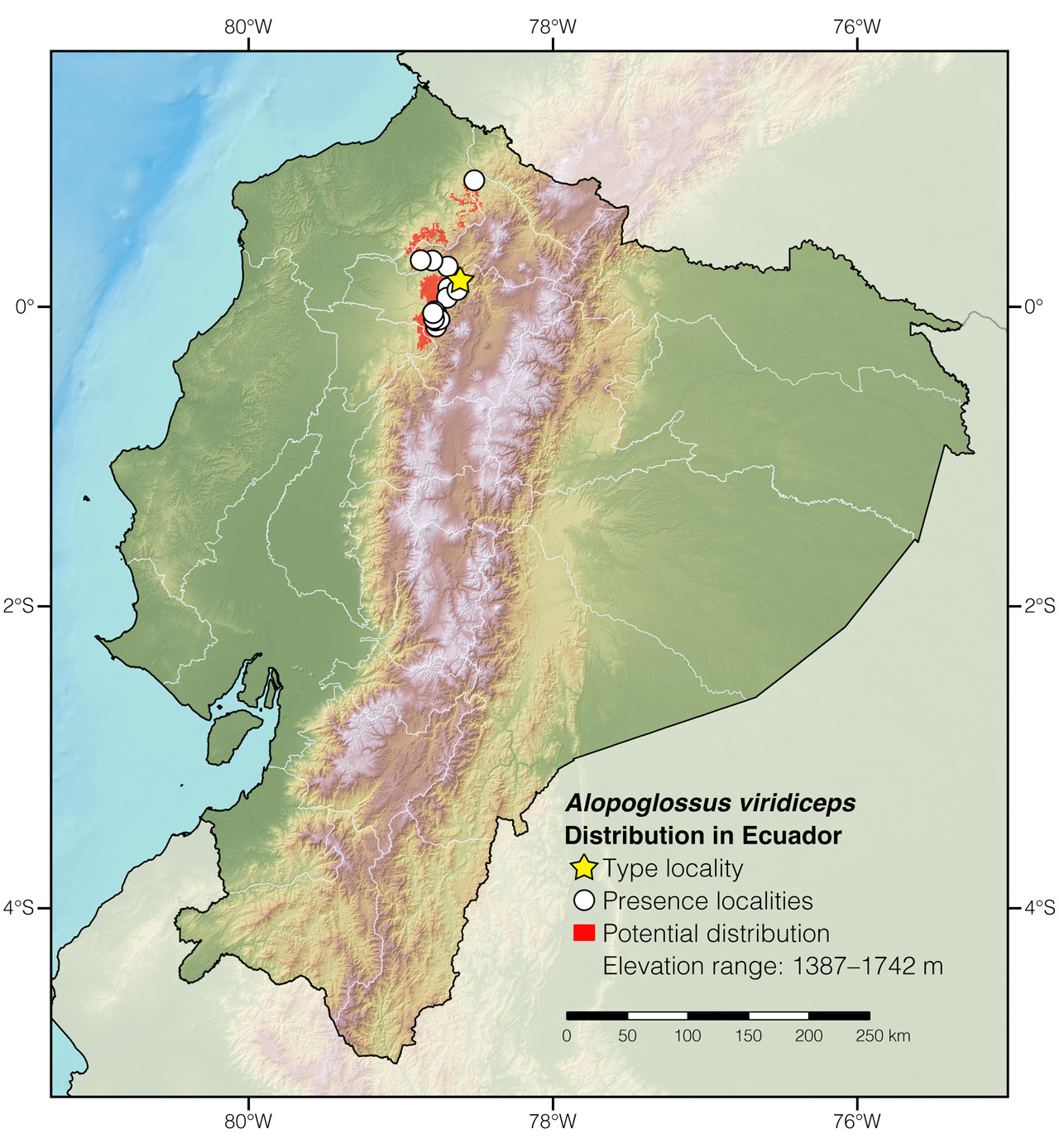

Distribution: Alopoglossus viridiceps is endemic to an area of approximately 1,694 km2 along the Pacific slopes of the Andes in northwestern Ecuador (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Alopoglossus viridiceps in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Alopoglossus, which is derived from the Greek words alopekia (=bare) and glossa (=tongue),10 refers to the tongue of lizards of this genus, which lacks scale-like papillae.11,12 The specific epithet viridiceps, which comes from the Latin word viridis (=green) and ceps (=head), refers to the dorsal coloration of the head in this species.1

See it in the wild: Green-headed Shade-Lizards can be seen with relative ease in Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve and Séptimo Paraíso Lodge. These lizards can be spotted as they forage in leaf-litter during sunny mornings along forest trails. They may also be found at night by removing leaf-litter or by searching under rocks and logs.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks to Lina Parra for helping compile some of the information used in this account.

Special thanks to Sabrina Stuster-Jansen for symbolically adopting the Green-headed Shade-Lizard and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Vieira J, Arteaga A (2021) Green-headed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus viridiceps). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/NFNC9760

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal O, Lobos SE (2014) A new species of Alopoglossus lizard (Squamata, Gymnophthalmidae) from the tropical Andes, with a molecular phylogeny of the genus. ZooKeys 410: 105–120. DOI: 10.3897/zookeys.410.7401

- Köhler G, Hans-Helmut D, Veselý M (2012) A contribution to the knowledge of the lizard genus Alopoglossus (Squamata: Gymnophthalmidae). Herpetological Monographs 26: 173–188. DOI: 10.1655/HERPMONOGRAPHS-D-10-00011.1

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Arteaga A, Pyron RA, Peñafiel N, Romero-Barreto P, Culebras J, Bustamante L, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Guayasamin JM (2016) Comparative phylogeography reveals cryptic diversity and repeated patterns of cladogenesis for amphibians and reptiles in northwestern Ecuador. PLoS ONE 11: e0151746. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151746

- Savit AZ (2006) Reptiles of the Santa Lucía Cloud Forest, Ecuador. Iguana 13: 94–103.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Vitt LJ, De la Torre S (1996) A research guide to the lizards of Cuyabeno. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, 165 pp.

- IUCN (2001) IUCN Red List categories and criteria: Version 3.1. IUCN Species Survival Commission, Gland and Cambridge, 30 pp.

- Guayasamin JM, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Vieira J, Kohn S, Gavilanes G, Lynch RL, Hamilton PS, Maynard RJ (2019) A new glassfrog (Centrolenidae) from the Chocó-Andean Río Manduriacu Reserve, Ecuador, endangered by mining. PeerJ 7: e6400. DOI: 10.7717/peerj.6400

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Harris DM (1994) Review of the teiid lizard genus Ptychoglossus. Herpetological Monographs 8: 226–275. DOI: 10.2307/1467082

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Alopoglossus viridiceps in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | El Cristal | Crump & Lynch 1995 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Charguayacu Alto | Köhler 2012 |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Reserva Los Cedros | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Reserva Río Manduriacu | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Cascadas de Mindo | Photo by Peter Muddle |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hacienda San Vicente | Torres-Carvajal & Lobos 2014 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegal | USNM 196086 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Nanegalito | USNM 163447 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Santa Lucía Cloud Forest Reserve* | Torres-Carvajal & Lobos 2014 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Saragoza–Río Cinto | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Séptimo Paraíso Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Bosque Protector Mindo-Nambillo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Reserva Río Bravo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Río Nambillo | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Vía a Mindo | iNaturalist |