Published June 20, 2020. Updated February 26, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Greater Ground Snake (Atractus major)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Atractus major

English common names: Greater Ground Snake, Big Ground Snake.

Spanish common name: Tierrera grande, culebra tierrera mayor.

Recognition: ♂♂ 53.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=51.2 cm. ♀♀ 98.6 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=85.2 cm..1,2 Atractus major can be recognized by its large size, small eyes, and dorsal pattern consisting of 21–52 pale-edged dark blotches or bands on a pale brown background color (Fig. 1).1–4 Most individuals have a short dark stripe on the neck.4,5 In Ecuadorian Amazonia, the most similar species are A. pachacamac and A. arangoi, both of which lack a dark mid-dorsal stripe on the neck.4 Atractus atlas occurs at higher elevation than A. major and also lacks a dark mid-dorsal stripe on the neck.6

Figure 1: Individuals of Atractus major: Huella Verde lodge, Pastaza province, Ecuador (); Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, Napo province, Ecuador (); Palmarí, Amazonas state, Brazil (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Atractus major is a semi-fossorial snake that inhabits primary and secondary rainforests,7 forest clearings,3 crops,8 and rural areas.9 Greater Ground Snakes are primarily nocturnal,5,7–11 although diurnal activity has also been recorded.5,12,13 They may be observed active on the ground, in leaf-litter,3 concealed beneath rocks, logs,3,7,10 and even climbing on low vegetation.7,8 Atractus major feeds primarily on giant earthworms3,6,7,13 and occasionally on insects,7,14 which are actively searched for and then captured and swallowed whole.5 Defensive behaviors include flattening the body, hiding the head under body coils,7 and poking with the tail.10 The only known predators of this species are coralsnakes (Micrurus surinamensis and Micrurus obscurus).10,15 In some parts of the Amazon, hatching in A. major coincides with periods of low rainfall.7 Females containing 3–12 eggs have been found,16 but the real clutch size is unknown.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..17 Atractus major is listed in this category because the species has a large distribution, uses a wide range of habitat types, occurs in protected areas, and lacks major immediate extinction threats.17 The impact of human activities on Ecuadorian populations of A. major is not clear, however, there are records of traffic mortality.18

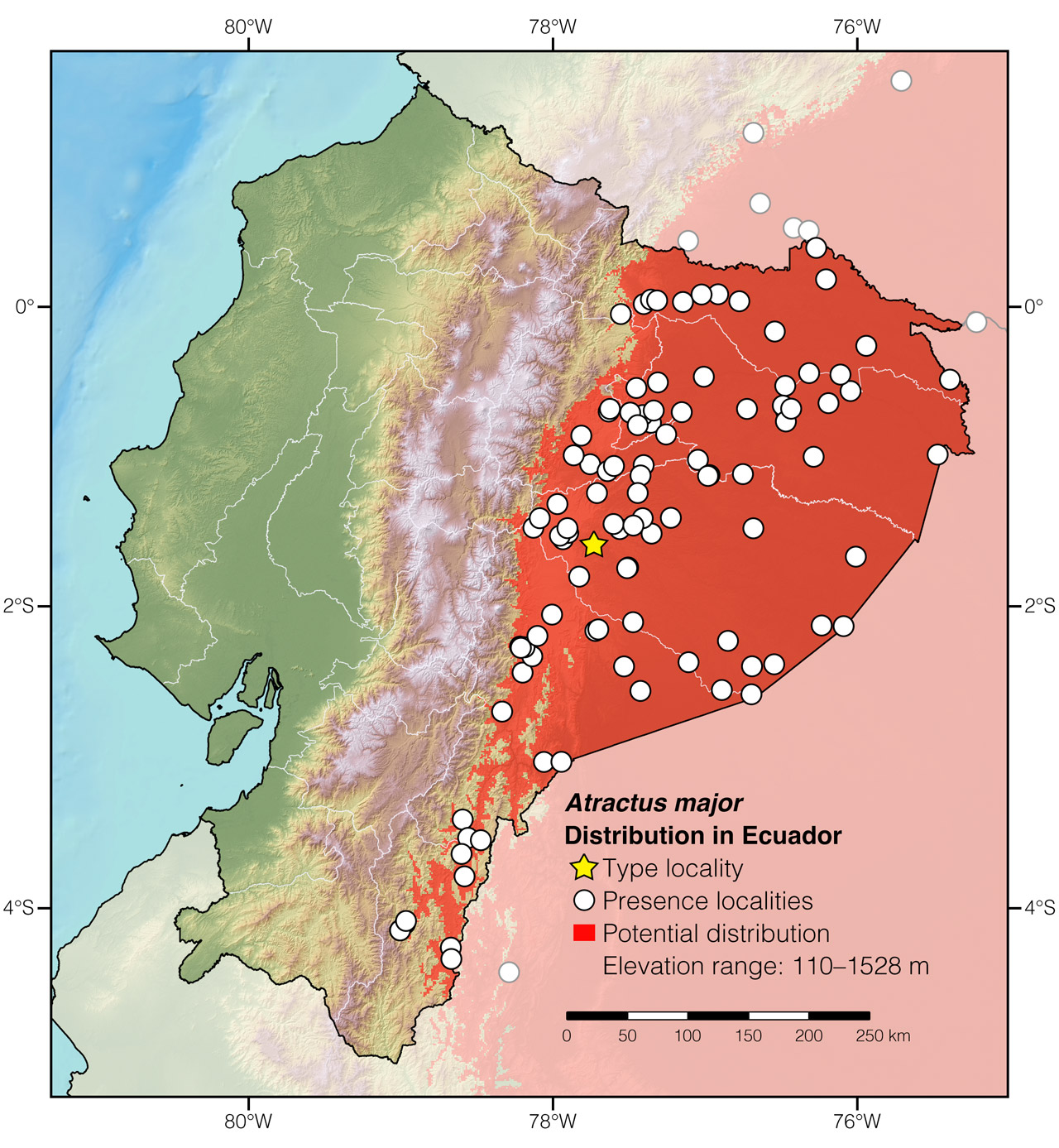

Distribution: Atractus major is native to an area of approximately 403,448 km2 throughout the Amazon basin and adjacent foothills of the Andes in Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Peru, and Venezuela.19

Figure 2: Distribution of Atractus major in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Canelos, Pastaza province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Atractus, which is a latinization of the Greek word άτρακτος (=spindle),20–22 probably refers to the fact that snakes of this genus have a uniform width throughout the body and a narrow tail, resembling an antique spindle used to spin fibers. The specific epithet major is a Latin word meaning “greater.” It probably refers to the comparatively large body size of this species.

See it in the wild: Atractus major is found at a rate of about once every few weeks throughout the Amazon of Ecuador. Some of the best localities to find snakes of this species are: Yasuní Scientific Station, Tiputini Biodiversity Station, Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, and Tamandúa Ecological Reserve. The snakes are most easily located by scanning the forest floor and leaf-litter along trails at night.

Authors: Duvan ZambranoaAffiliation: Universidad del Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,cAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador., Frank Pichardo,cAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di DoménicoeAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Zambrano D, Arteaga A (2024) Greater Ground Snake (Atractus major). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/XPYM6795

Literature cited:

- Boulenger G (1894) Catalogue of the snakes in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 382 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.8316

- Savage JM (1960) A revision of the Ecuadorian snakes of the colubrid genus Atractus. Miscellaneous Publications, Museum of Zoology, University of Michigan 112: 1–86.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Schargel WE, Lamar WW, Passos P, Valencia JH, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Campbell JA (2013) A new giant Atractus (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) from Ecuador, with notes on some other large Amazonian congeners. Zootaxa 3721: 455–474. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3721.5.2

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Passos P, Scanferla A, Melo-Sampaio PR, Brito J, Almendariz A (2018) A giant on the ground: another large-bodied Atractus (Serpentes: Dipsadinae) from Ecuadorian Andes, with comments on the dietary specializations of the goo-eaters snakes. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências 91: e20170976. DOI: 10.1590/0001-3765201820170976

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1998) Natural history of snakes in forests of the Manaus region, Central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History 6: 78–150.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Silva Haad JJ (2004) Las serpientes del género Atractus Wagler, 1828 (Colubridae, Xenodontinae) en la Amazonía colombiana. Revista de la Academia Colombiana de Ciencias Exactas, Físicas y Naturales 28: 1–446.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Natera-Mumaw M, Esqueda-González LF, Castelaín-Fernández M (2015) Atlas serpientes de Venezuela. Dimacofi Negocios Avanzados S.A., Santiago de Chile, 456 pp.

- Duellman WE, Salas AW (1991) Annotated checklist of the amphibians and reptiles of Cuzco Amazónico, Peru. Occasional Papers of the Museum of Natural History, the University of Kansas 143: 1–13.

- dos Santos-Costa MC, Maschio GF, Prudente AL (2015) Natural history of snakes from Floresta Nacional de Caxiuanã, eastern Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetology Notes 8: 69–98.

- Martins M, Oliveira ME (1993) The snakes of the genus Atractus Wagler (Reptilia: Squamata: Colubridae) from the Manaus region, central Amazonia, Brazil. Zoologische Mededelingen 67: 21–40.

- Field notes of Marcos Scarello.

- Esqueda LF, La Marca E (2005) Revisión taxonómica y biogeográfica (con descripción de 5 nuevas especies) del genero Atractus (Colubridae: Dipsadinae) en los Andes de Venezuela. Herpetotropicos 2: 1–32.

- Nogueira C, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Catenazzi A, Gonzales L, Schargel W, Rivas G (2016) Atractus major. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org

- Filius J, van der Hoek Y, Jarrín‐V P, van Hooft P (2020) Wildlife roadkill patterns in a fragmented landscape of the Western Amazon. Ecology and Evolution 10: 6623–6635. 10.1002/ece3.6394

- Nogueira CC, Argôlo AJS, Arzamendia V, Azevedo JA, Barbo FE, Bérnils RS, Bolochio BE, Borges-Martins M, Brasil-Godinho M, Braz H, Buononato MA, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Colli GR, Costa HC, Franco FL, Giraudo A, Gonzalez RC, Guedes T, Hoogmoed MS, Marques OAV, Montingelli GG, Passos P, Prudente ALC, Rivas GA, Sanchez PM, Serrano FC, Silva NJ, Strüssmann C, Vieira-Alencar JPS, Zaher H, Sawaya RJ, Martins M (2019) Atlas of Brazilian snakes: verified point-locality maps to mitigate the Wallacean shortfall in a megadiverse snake fauna. South American Journal of Herpetology 14: 1–274. DOI: 10.2994/SAJH-D-19-00120.1

- Woodward SP, Tate R (1830) A manual of the Mollusca: being a treatise on recent and fossil shells. C. Lockwood and Company, London, 750 pp.

- Beekes R (2010) Etymological dictionary of Greek. Brill, Boston, 1808 pp.

- Duponchel P, Chevrolat L (1849) Atractus. In: d’Orbigny CD (Ed) Dictionnaire universel d’histoire naturelle. MM. Renard, Martinet et Cie., Paris, 312.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Atractus major in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Estación de Campo Macagual | Calderón et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mansoyá | Geopark Colombia 2022 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Mocoa | Passos & Fernandes 2008 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Puerto Caicedo | Passos & Fernandes 2008 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Putumayo | Grant et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda Islas de Cartagena | Borja-Acosta & Galeano 2024 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Bosque Protector Abanico | Lozano & Medranda 2008 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Centro Shuar Kiim | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Chiguaza | USNM 232690; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Finca El Piura | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Gualaquiza | Savage 1960 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Passos & Fernandes 2008 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas–Riobamba road | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Méndez, environs of | USNM 232692; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Paantim | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Abanico | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Santiago | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | San Pedro de Chumpias | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Photo by Axel Marchelie |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Turula | AMNH 35966; examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Villa Ashuara | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Alto Sindi | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Comunidad Gareno | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huataraco | USNM 232653; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Lago Agrio | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco, 3 km S of | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Cotopino | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Pucuno | USNM 232650; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Suno | USNM 232658; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Shushufindi, Río Aguarico | USNM 232660; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sinchi Sacha | Photo by Ernesto Arbeláez |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena, av. Muyuna | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Whitworth & Beirne 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Zoo el Arca | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Boca del Río Coca | Passos et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Kupi, 5 km NE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | USNM 232656; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nenkepare | Photo by Etienne Littlefair |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | NPF, 5 km N of | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tambococha | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiguino | Passos et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Vía Pompeya Sur–Iro | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarentaro | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuni Scientific Station | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yuturi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | 5 km S de Campo Yuralpa, Plataforma Waponi | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Curaray | USNM 232671; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | USNM 232670; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arutam Field Station | SMF; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Betwen Puyo and Macas | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Bobonaza | USNM 232680; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campo K10 | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos* | Boulenger 1894 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Charapacocha | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chichirota | USNM 232674; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Copataza | USNM 232666; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Curaray | Passos & Fernandes 2008 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Guache | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Hacienda San Francisco | Savage 1961 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Huella Verde Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Lorocachi | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Manderoyacu | Passos et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | USNM 232672; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | USNM 232667; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Sarayakillo | Arteaga et al. 2022 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Talin | USNM 232675; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Tigre | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | USNM 232676; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Savage 1960 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay In Situ | Bentley et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tamandúa Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tarangaro | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | UNOCAL Base Camp | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano B | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Bocana Río Cuyabeno | Passos et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Duvuno | Passos et al. 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | MHNG 2250.033; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Gonzalo Pizarro | Photo by John Castillo |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui | MCZ 166523; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lumbaqui, parroquia urbana | Dueñas and Báez 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Pañachoca | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río San Miguel | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Elena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Territorio Cofán Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alto Machinaza | Almendáriz et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Bombuscaro | Mejía Guerrero 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Cabañas Yakuam | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Copalinga Lodge | Photo by Aaron Hulsey |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Pangui | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Parque Nacional Podocarpus | Darwin Núñez |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Reserva Natural Maycu | Arteaga et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Valle del Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Schargel et al. 2013 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Paagat | USNM 316576; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Campo Santa Clara | USNM 127120; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Centro Unión | Dixon & Soini 1986 |

| Perú | Loreto | Mishana | Passos et al. 2012 |

| Perú | Loreto | Zona Reservada Güeppi | iNaturalist; photo examined |