Published October 18, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Yasuní Floodplain Skink (Varzea yasuniensis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Scincidae | Varzea yasuniensis

English common name: Yasuní Floodplain Skink.

Spanish common name: Lagartija lisa del Yasuní.

Recognition: ♂♂ 20.0 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=7.2 cm..1 The Yasuní Floodplain Skink (Varzea yasuniensis) stands out distinctly from most other lizards found in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. It is characterized by its shiny smooth dorsal scales, which are uniform in size and similar in dimensions to the ventral scales.1 The dorsum is pale brown with a bronze sheen, accompanied by broad black dorsolateral stripes and a few longitudinally aligned dark brown spots usually restricted to the scale tips (Fig. 1). Juveniles of this species have a bluish sheen on the upper side of the tail.2 Unlike other lizards with smooth scales (like Iphisa brunopereira), the dorsal scales of all Ecuadorian skinks are cycloid, overlapping, and arranged in oblique rows.3,4 This species can readily be identified from the other two Ecuadorian skinks (Copeoglossum nigropunctatum and Varzea altamazonica) by having four supraciliary scales, of which the second is elongated.1 This species further differs from Copeoglossum nigropunctatum by having seven supralabials, with the fifth being the largest and located under the eye (eight supralabials, with the sixth being the largest and located under the eye in the other species), and parietals in contact posterior to interparietal (no contact in the other species).1

Figure 1: Adult of Varzea yasuniensis from Yarina Lodge, Orellana province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Varzea yasuniensis is a primarily terrestrial skink that occurs in higher densities in semi-open areas along floodplain forests, which may be old growth or moderately disturbed.1 The species appears to be more common in clearings, tree fall areas, forest edges, and peri-urban areas.1,5 Yasuní Floodplain Skinks are diurnal and terrestrial to fully arboreal. They occupy all strata of the rainforest, from the forest floor to the branches of emergent trees at 40 m above the ground,1,6 as well as man-made structures such as wooded boardwalks and thatched roofs.6 This species is heliophilic, meaning its activity is restricted to periods of direct sunlight.6 Individuals are often seen foraging or basking on logs, tree trunks, branches, and thatched roofs under these conditions. Conversely, during overcast days or at nighttime, they are nowhere to be seen. Amazonian skinks in general are active foragers that feed primarily on insects,7–10 but the diet of V. yasuniensis is not known. When confronted with threats, these cautious reptiles swiftly evade observers by darting into thick vegetation.6 They are also quick to shed their tail as a distraction to predators.6 Amazonian skinks are viviparous,4 but the gestation period and brood sizes of V. yasuniensis are not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances.. Varzea yasuniensis is a recently described species.1 Therefore, its conservation status has not been evaluated by the IUCN Red List. Here, it is provisionally assigned to the LC category because the species has a wide distribution throughout the Ecuadorian Amazon and it is comparatively common and abundant in some areas. Moreover, anecdotal observations6 indicate that this species not only tolerates, but actually benefits from, the conversion of dense-canopy rainforests to semi-open environments. Although the range of V. yasuniensis overlaps in its entirety with the Yasuní National Park, this protected area still faces major threats including oil extraction and road constructions.1

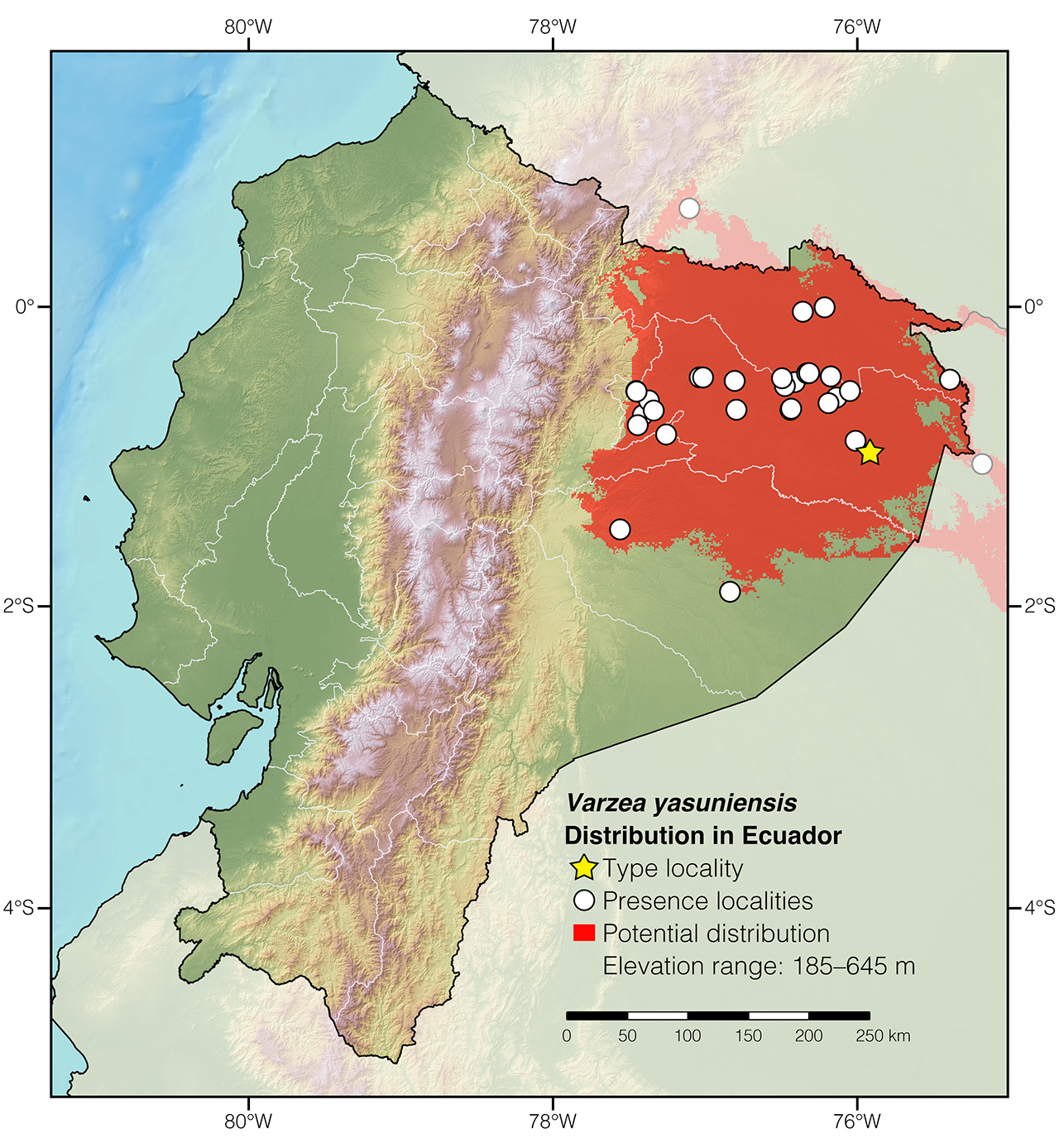

Distribution: Varzea yasuniensis is native to the northern Ecuadorian Amazon lowlands where it occurs primarily below 500 m in elevation along the floodplains of large rivers, including the Napo, Aguarico, Tiputini, and Bobonaza. The presence of this species is predicted in Colombia and Perú, where there are two unconfirmed records that may belong to V. yasuniensis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Distribution of Varzea yasuniensis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Río Rumiyacu, Orellana province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Varzea is a pre-Roman Portugese word, Iberian in origin, that means “flooded river bank.” It refers to the apparent preferred habitat of the included species.3 The specific epithet yasuniensis refers to the Yasuní National Park, where V. yasuniensis was discovered.1 With 9,820 km2, Yasuní is the largest protected area in continental Ecuador and one of the most biodiverse places on Earth.11 In 1989 Yasuní was declared a UNESCO Biosphere Reserve.1

See it in the wild: Yasuní Floodplain Skinks can be observed sporadically along semi-open areas throughout their range in Ecuador, particularly along the Río Napo. The species is considered locally common at Yarina Lodge and Yasuní Scientific Station. Individuals can be seen more easily during sunny days by scanning logs and tree trunks along forest borders and clearings.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Sebastián Di DoménicobAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Yasuní Floodplain Skink (Varzea yasuniensis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/XEKG5720

Literature cited:

- Torres-Carvajal T, Sandoval C, Paucar DA (2024) The skinks (Squamata: Scincidae) of Ecuador, with description of a new Amazonian species. Vertebrate Zoology 74: 551–564. DOI: 10.3897/vz.74.e130147

- Paucar DA (2024) Mabuya yasuniensis. In: Torres-Carvajal O, Pazmiño-Otamendi G, Ayala-Varela F, Salazar-Valenzuela D (Eds) Reptiles del Ecuador Versión 2022.0 Museo de Zoología, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador. Available from: https://bioweb.bio

- Hedges SB, Conn CE (2012) A new skink fauna from Caribbean islands (Squamata, Mabuyidae, Mabuyinae). Zootaxa 3288: 1–244. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3288.1.1

- Miralles A, Barrio-Amoros CL, Rivas GA, Chaparro-Auza JC (2006) Speciation in the “Varzea” flooded forest: a new Mabuya (Squamata, Scincidae) from western Amazonia. Zootaxa 1188: 1–22. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.1188.1.1

- María José Quiroz, field observation.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Vitt LJ, Blackburn DG (1991) Ecology and life history of the viviparous lizard Mabuya bistriata (Scincidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. Copeia 1991: 916–927. DOI: 10.2307/1446087

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Bass MS, Finer M, Jenkins CN, Kreft H, Cisneros-Heredia DF, McCracken SF, Pitman NCA, English PH, Swing K, Villa G, Di Fiore A, Voigt CC, Kunz TH (2010) Global conservation significance of Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park. PLoS ONE 5: e8767. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008767

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Varzea yasuniensis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Reserva La Isla Escondida | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Cotopino | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | San Jose Viejo de Sumaco | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Beirne et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Oasis | Paucar 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Comunidad Oasis | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Parcela 50 ha | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pozo Edén | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | PUCE scientific station | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Puerto Yuturi | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Reserva Río Bigal | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Pucuno | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Rumiyacu | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yanayacu | Paucar 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Rumiyacu River mouth, 6 km S of* | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Taracoa | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campo K10 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Jatun Yaku | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE en Cuyabeno | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente Río Cuyabeno | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Thomas et al. 2020 |

| Perú | Loreto | Cabo Pantoja | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |