Published August 22, 2023. Updated October 19, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Upper-Amazon Skink (Varzea altamazonica)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Scincidae | Varzea altamazonica

English common names: Upper-Amazon Skink, South American spotted Skink.

Spanish common name: Lagartija lisa altamazónica.

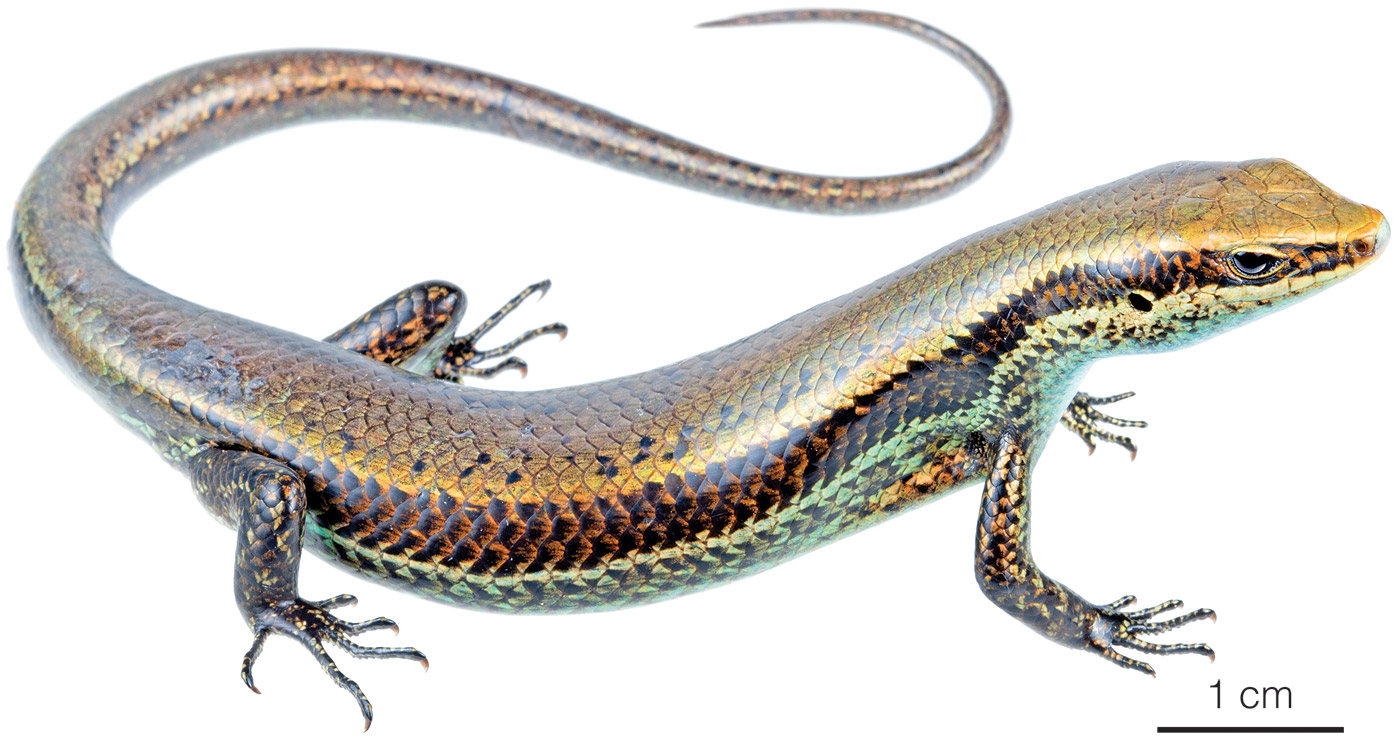

Recognition: ♂♂ 17.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=8.7 cm. ♀♀ 18.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=9.2 cm..1,2 The Upper-Amazon Skink (Varzea altamazonica) stands out distinctly from most other lizards found in the Ecuadorian Amazon rainforest. It is characterized by its shiny smooth dorsal scales, which are uniform in size and similar in dimensions to the ventral scales.3 The dorsum is pale brown with a bronze sheen, accompanied by broad black dorsolateral stripes (Fig. 1).2 Juveniles of this species have a bluish sheen on the upper side of the tail. Unlike other lizards with smooth scales (like Iphisa brunopereira), the dorsal scales of V. altamazonica are cycloid, overlapping, and arranged in oblique rows.3 This species is often confused with the two other skinks that inhabit the Ecuadorian Amazon region. From Copeoglossum nigropunctatum, it differs by having parietal scales in contact behind the interparietal and seven (instead of eight or nine) supralabials, with the fifth (instead of the sixth) being the largest and placed under the eye.1 From V. yasuniensis, it differs by having five subequal (instead of four, of which the second is elongated) supraciliary scales.4 Therefore, close examination is needed to separate the two species.

Figure 1: Adult of Varzea altamazonica from Río Curaray, Pastaza province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Varzea altamazonica is a primarily terrestrial skink that occurs in higher densities in semi-open areas in old growth to moderately disturbed rainforests, which may be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.3,5 The species prefers clearings, tree fall areas, forest edges, and peri-urban areas.2,6 Upper-Amazon Skinks are diurnal and terrestrial to fully arboreal.5,6 They occupy all strata of the rainforest, from the forest floor to the branches of emergent trees at 37 m above the ground.6,7 Moreover, these skinks have been observed to inhabit man-made structures such as fences, walls, and thatched roofs.2,6 This reptile is considered a heliophilic, meaning its activity is restricted to periods of direct sunlight.2,6 Individuals are often seen foraging or basking on logs, tree trunks, large branches overhanging the water, and thatched roofs under these conditions.5,6 Conversely, during overcast days or at nighttime, they are nowhere to be seen, and are presumed to take shelter in crevices or under bark.6 Amazonian skinks in general are active foragers that feed primarily on insects,8–11 but the diet of V. altamazonica is largely unknown. There is only an unpublished photographic record of an individual in Yasuní National Park feeding on an unidentified cricket species. When confronted with threats, these cautious reptiles swiftly evade observers by darting into thick vegetation.6 They are also quick to shed their tail as a distraction to predators.6 Varzea altamazonica is a viviparous species,1 but the gestation period and brood sizes are not known.

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..12 Varzea altamazonica is listed in this category because the species has a wide distribution throughout the western Amazon basin and it is comparatively common and abundant in most areas. Moreover, anecdotal observations in Ecuador6 indicate that this species not only tolerates, but actually benefits from, conversion of dense-canopy rainforests to semi-open environments.

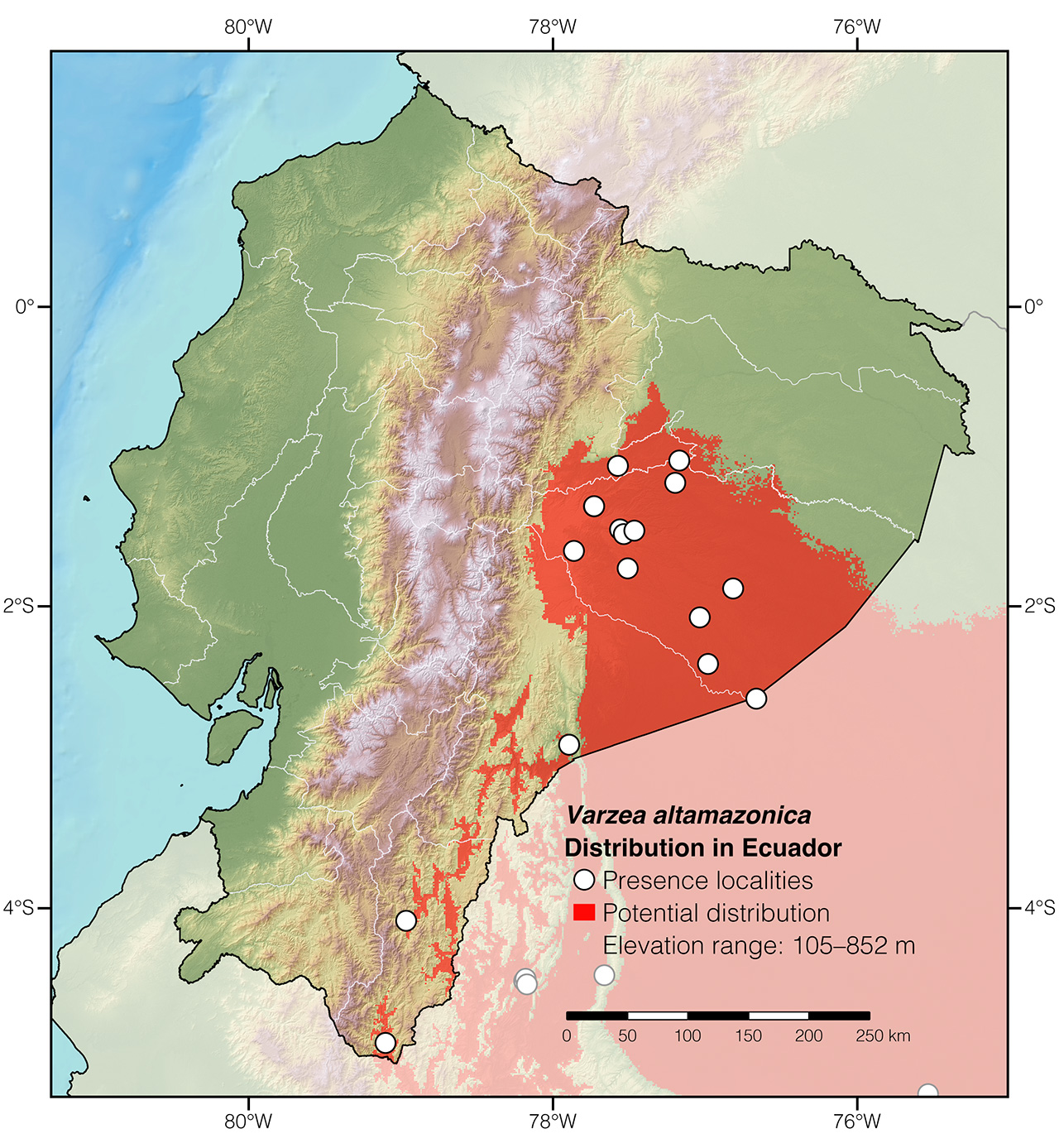

Distribution: Varzea altamazonica is native to the western Amazon basin of Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), Perú and Bolivia.

Figure 2: Distribution of Varzea altamazonica in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The genus name Varzea is a pre-Roman Portugese word, Iberian in origin, that means “flooded river bank.” It refers to the apparent preferred habitat of the included species.3 The specific epithet altamazonica refers to the upper Amazon basin, where the species occurs.1

See it in the wild: Upper-Amazon Skinks can be observed sporadically along semi-open areas throughout their area of distribution in Ecuador, particularly along the Bobonaza and Curaray rivers. The species is locally common at Finca Heimatlos. Individuals can be seen more easily during sunny days by scanning logs and tree trunks along forest borders.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2024) Upper-Amazon Skink (Varzea altamazonica). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/ZVND1454

Literature cited:

- Miralles A, Barrio-Amoros CL, Rivas GA, Chaparro-Auza JC (2006) Speciation in the “Varzea” flooded forest: a new Mabuya (Squamata, Scincidae) from western Amazonia. Zootaxa 1188: 1–22. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.1188.1.1

- Thomas O, Bird D, O’Donovan G (2020) The fish and herpetofauna of the Sani Reserve, Ecuador. Operation Wallacea, Lincolnshire, 262 pp.

- Hedges SB, Conn CE (2012) A new skink fauna from Caribbean islands (Squamata, Mabuyidae, Mabuyinae). Zootaxa 3288: 1–244. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.3288.1.1

- Torres-Carvajal T, Sandoval C, Paucar DA (2024) The skinks (Squamata: Scincidae) of Ecuador, with description of a new Amazonian species. Vertebrate Zoology 74: 551–564. DOI: 10.3897/vz.74.e130147

- Ribeiro-Junior MA, Amaral S (2016) Catalogue of distribution of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) from the Brazilian Amazonia. III. Anguidae, Scincidae, Teiidae. Zootaxa 4205: 401–430. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.4205.5.1

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Photo by Carmelo López.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Vitt LJ, Blackburn DG (1991) Ecology and life history of the viviparous lizard Mabuya bistriata (Scincidae) in the Brazilian Amazon. Copeia 1991: 916–927. DOI: 10.2307/1446087

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Cisneros-Heredia DF, Yánez-Muñoz M, Brito J, Valencia J, Perez P, Avila-Pires TCS, Aparicio J, Moravec J (2021) Varzea altamazonica. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T44579239A44579243.en

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Varzea altamazonica in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Amaru Shuar community | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Ahuano | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Campo K10 | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Kurintza | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Comunidad Paparawua | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Curaray Medio | This work; Fig. 1 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Estación Científica Oglán | Carvajal-Campos & Torres-Carvajal 2018 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Finca Heimatlos | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Oglán Scientific Station | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Capahuari | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Conambo | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sarayacu | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Río Mayo | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2024 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aintami | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Chazuta | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Huampami | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | La Poza | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Puerto Galilea | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | San Antonio, Río Cenepa | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Teniente Pinglo | Miralles et al. 2006 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Gota de Agua | Photo by Claudia Koch |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Loreto | Mouth of Río Tigre | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Loreto | Quache | Miralles et al. 2006 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Samiria | Ribeiro-Junior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | San Martín | Tarapoto, 34 km N of | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Perú | San Martín | Yarina | Miralles et al. 2006 |