Published March 20, 2018. Updated January 5, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Southern Turniptail Gecko (Thecadactylus solimoensis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Phyllodactylidae | Thecadactylus solimoensis

English common name: Southern Turniptail Gecko.

Spanish common names: Geco colabarril del sur, salamanquesa gigante oriental.

Recognition: ♂♂ 21.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=10.8 cm. ♀♀ 21.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=11.2 cm..1,2 Thecadactylus solimoensis is the largest and most robust gecko in Ecuador. In the Amazonian provinces, it is the only one having webbed digits. These characteristics, coupled with the absence of movable eyelids, the presence of a vertically elliptical pupil, and the small granular dorsal scales (Fig. 1), will readily differentiate this species from any other Amazonian lizard in Ecuador.1–3 The introduced gekkonids Hemidactylus frenatus and Hemidactylus mabouia are smaller in body size and have unwebbed fingers.

Figure 1: Individuals of Thecadactylus solimoensis: Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve, Napo province, Ecuador (); Palmarí Reserve, Amazonas state, Brazil (); Tamandúa Reserve, Pastaza province, Ecuador (); Huella Verde Lodge, Pastaza province, Ecuador (). sa=subadult, j=juvenile.

Natural history: Thecadactylus solimoensis is a nocturnal gecko that inhabits pristine to moderately disturbed rainforest, which may be terra-firme or seasonally flooded.1–3 The species is also present in plantations and human settlements.1–5 At night, Southern Turniptails are active on logs, banana plants, or on tree trunks up to 36 m above the ground.1–7 In human settlements, they colonize walls and rooftops usually close to electric lights.6 By day, these geckos remain hidden in crevices, arboreal bromeliads, and under bark.5,8 Interactions between individuals include producing guttural sounds, tremulous waving of the tail, and headlong fights.9 When disturbed, their usual response is to move to the opposite side of tree trunk or to flee into crevices.5 Other defense mechanisms include parachuting and shedding off the tail.7 The shedding of the tail implies losing a source of energy storage,9 but, when regenerated, the new tail is thicker than the original tail. Thecadactylus solimoensis is an ambush predator5 that feeds on a variety of invertebrates including roaches, grasshoppers, crickets, moths, beetles, ants, spiders, scorpions, and snails.2,5,10,11 There are recorded instances of predation on members of this species, including by bats, snakes (Corallus batesii, Oxybelis fulgidus, and Bothrops bilineatus), and owls.6,12–14 Clutches consist of a single egg2,9 laid under the bark of trees.5

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..15 Thecadactylus solimoensis is listed in this category because the species is widely distributed, survives in human-modified environments, and is considered to be undergoing no obvious population declines nor facing major immediate threats of extinction.

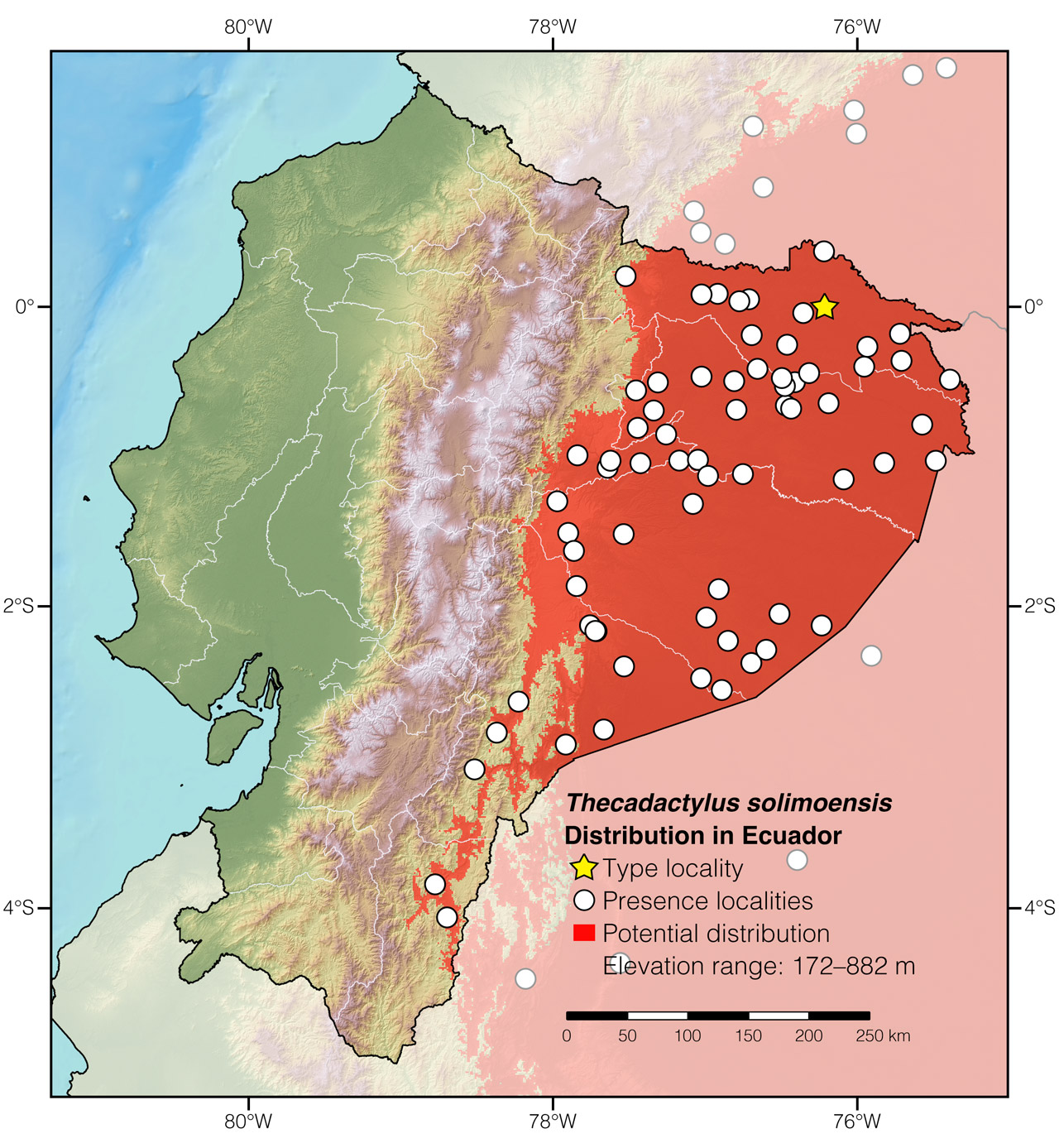

Distribution: Thecadactylus solimoensis is native to the western Amazon basin of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Thecadactylus solimoensis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: Cuyabeno, Sucumbíos province. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Thecadactylus comes from the Greek words theke (=envelope) and daktylos (=finger),16 and refers to the skin-covered claws. The specific epithet solimoensis refers to the Solimões River, which drains much of the area in which the species occurs.3

See it in the wild: In Ecuador, Thecadactylus solimoensis is considered a locally abudant species throughout the Amazonian lowlands of Ecuador. For example, these geckos are guaranteed sightings on buildings and other man-made structures at Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve and Tiputini Biodiversity Station.

Special thanks to Billy Sveen for symbolically adopting the Southern Turniptail Gecko and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Gabriela AguiarbIndependent researcher, Quito, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,cAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Sebastián Di Doménico,eAffiliation: Keeping Nature, Bogotá, Colombia. and Amanda QuezadacAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Aguiar G (2024) Southern Turniptail Gecko (Thecadactylus solimoensis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/MQIM3901

Literature cited:

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Miscellaneous Publications of the Museum of Natural History University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco Amazónico: The lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Comstock Publishing Associates, London, 433 pp.

- Bergmann PJ, Russell AP (2007) Systematics and biogeography of the widespread Neotropical gekkonid genus Thecadactylus (Squamata), with the description of a new cryptic species. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149: 339–370. DOI: 10.1111/j.1096-3642.2007.00251.x

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Vitt LJ and De La Torre S (1996) A research guide to the lizards of Cuyabeno. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, Quito, 165 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Pianka ER, Vitt LJ (2003) Lizards: Windows to the evolution of diversity. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles, 333 pp.

- McCracken SF, Forstner MRJ (2014) Herpetofaunal community of a high canopy tank bromeliad (Aechmea zebrina) in the Yasuní Biosphere Reserve of Amazonian Ecuador, with comments on the use of “arboreal” in the herpetological literature. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 8: 65–75.

- Vitt LJ, Zani PA (1997) Ecology of the nocturnal lizard Thecadactylus rapicauda (Sauria: Gekkonidae) in the Amazon region. Herpetologica 53: 165–179.

- Jordán JC, Suárez JS, Sánchez L (2011) Notas sobre la ecología de Thecadactylus solimoensis (Squamata, Phyllodactylidae) de la Amazonía peruana. Revista Peruana de Biología 18: 257–260.

- Martins M (1991) The lizards of Balbina, Central Amazonia, Brazil: a qualitative analysis of resource utilization. Studies on Neotropical Fauna and Environment 26: 179–190.

- Meede U (1984) Herpetologische studien uber Echsen (Sauria) in einem begrenzten gebiet des Tropischen Regenwaldes in Peru: morphologische kriterien, autokologie und zoogeographie. Arten-liste der Reptilien im untersuchungsgebiet. PhD thesis, Hamburg, Germany: Universitat Hamburg.

- Venegas PJ, Chávez-Arribasplata JC, Almora E, Grilli P, Duran V (2019) New observations on diet of the South American two-striped forest-pitviper Bothrops bilineatus smaragdinus (Hoge, 1966). Arten-liste der Reptilien im untersuchungsgebiet. PhD thesis, Hamburg, Germany: Universitat Hamburg.

- Daza JD, Price LB, Schalk CM, Bauer AM, Borman AR, Peterhans JK (2017) Predation on Southern Turnip-tailed geckos (Thecadactylus solimoensis) by a Spectacled Owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata). Cuadernos de Herpetología 31: 37–39.

- Avila-Pires TCS, Caicedo J, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Gutiérrez-Cárdenas P, Perez P, Rivas G (2019) Thecadactylus solimoensis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T190507A44957121.en

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Thecadactylus solimoensis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Escombrera de Florencia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Reserva Doña Blanca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Reserva Natural El Arrullo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda La Gallineta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Centro Experimental Amazónico | Betancourth-Cundar & Gutiérrez-Zamora 2010 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Río Guamués | KU 140391; VertNet |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda La Jolla | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda La Unión | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Vereda Pueblo Viejo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cusuime | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Estación Biológica Wisui | Chaparro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Logroño | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Metsankim | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Pankints | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Torres-Carvajal 2018 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Rancho Quemado | MZUA.Re.0202; examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | USNM 204295; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Napo | Gareno | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Napo | Suchipakari | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | Photo by Tristan Schramen |

| Ecuador | Napo | Yachana Reserve | Whitworth & Beirne 2011 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Aeropuerto de Tiputini | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Coca | MHNG 2226.033; collection database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Concepción | USNM 204290; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Loreto | USNM 204287; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nenkepare | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Onkone Gare | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Torres-Carvajal 2018 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | García et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Nashiño | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Torres-Carvajal 2018 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Yasuní, near Lake Jatuncocha | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Maynard et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Shiripuno Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Taracoa | Ávila Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | Cisneros-Heredia 2003 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Achuar Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Bobonaza | USNM 204284; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Chichirota | USNM 204281; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Conambo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Finca Heimatlos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Geyepare | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Juyuintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kapawi Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kukunk | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Kurintza | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Misión | Almendáriz 1987 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Montalvo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Bufeo | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Shionayacu | USNM 204285; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tamandúa | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | UNOCAL Base Camp | USNM 321058; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Dureno | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación PUCE en Cuyabeno* | Bergmann & Russell 2007 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Güeppicillo | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Selva Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | UIMNH 54545; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Margin of Zábalo river | Daza et al. 2017 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Napo Wildlife Center | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Playas del Cuyabeno | UIMNH 91671; collection database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puente sobre el Río Cuyabeno | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sábalo Village | Reptiles of Ecuador book |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sacha Lodge | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pablo de Kantesiya | Avila-Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pedro de los Cofanes | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sani Lodge | Thomas et al. 2020 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Duellman 1978 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Elena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi | Photo by Fausto Cornejo |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Territorio Cofán Dureno | Yánez-Muñoz & Chimbo 2007 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Guayzimi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza | Pazmiño-Otamendi & Torres-Carvajal 2018 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Aguaruna Village | MVZ 163043; VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Caterpiza | MVZ 174998, VertNet |

| Perú | Amazonas | Puerto Galilea | USNM 568704; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | Cerro de Kampankis | Catenazzi & Venegas 2016 |

| Perú | Loreto | Loboyacu | Jordán et al. 2011 |

| Perú | Loreto | Moropon | TCWC 41199; VertNet |

| Perú | Loreto | San Jacinto | KU 222144; VertNet |

| Perú | San Martín | Bellavista | MCZ 17695; VertNet |