Published October 10, 2019. Updated November 13, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Common House-Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gekkonidae | Hemidactylus frenatus

English common names: Common House-Gecko, Asian House-Gecko.

Spanish common names: Geco común de casa, salamanquesa común.

Recognition: ♂♂ 13.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.5 cm. ♀♀ 12.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.0 cm..1 House geckos (genus Hemidactylus) can be identified from other lizards in Ecuador by their nocturnal habits, spine-like scales on the tail, expanded subdigital lamellae, lack of eyelids, and preference for man-made structures.2,3 Hemidactylus frenatus differs from H. mabouia by having low, rather than large and trihedral, tubercles on the dorsal surface of the body and tail and by lacking tubercles on the side of the head (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Individuals of Hemidactylus frenatus: Parque Nacional Soberanía, Panamá province, Panamá (); Churute, Guayas province, Ecuador (); Puerto Ayora, Galápagos province, Ecuador (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Hemidactylus frenatus is a nocturnal gecko that exhibits peak activity at dusk, dawn, and during warmer months.4–7 It occurs in high densities on walls, ceilings near electric lights,8,12,13 as well as on boulders and trees in human-altered environments12–14 spanning various lowland habitats, from deserts and rainforests to plantations.15–17 In daylight, these geckos remain concealed within crevices, lamps, beneath rocks, rotting logs, or virtually any object hanging vertically.18 Common House-Geckos are opportunistic predators that feed primarily on arthropods lured by artificial light sources,8,13,19 but also on mollusks and smaller geckos, including conspecifics.21–23 When threatened, they swiftly retreat into crevices or beneath surface objects, readily shedding their tails if captured.5,24 Throughout their range, Common House-Geckos fall prey to a variety of predators, including cats, snakes, rats, dogs, spiders, birds, praying mantids, and larger lizards,25,26 while also contending with parasitization by protozoans, mites, and various worms.27–30 Males exhibit social and aggressive behavior, employing calls and tail movements to attract females and establish and maintain territories.5,10,31,32 Females can store sperm for extended periods after mating,33 producing clutches of two water-resistant eggs throughout the year in tropical regions.18,34 These eggs are deposited in communal nesting sites, such as crevices, thatched roofs, or under ground debris, with a typical incubation period of 45 to 90 days.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..12 Hemidactylus frenatus is listed in this category because this species is widely-distributed, thrives in human-modified environments,36 and is expanding into new areas. As an invader, H. frenatus competitively displaces native geckos8,37,38 and other previously introduced species,21,39–41 often leading to their local extirpation.9,26,42 Populations of the Common House-Gecko have exploded following expansion of urban areas,26 and they are likely to keep thriving under current scenarios of global warming.42 They also have spread with the aid of commercial ships and cargo8,26,35 and have become naturalized on numerous islands.26,34 From a human-centered perspective, a positive outcome of the increased population densities of H. frenatus is the reduction in the number of pest insects such as mosquitoes and cockroaches.43

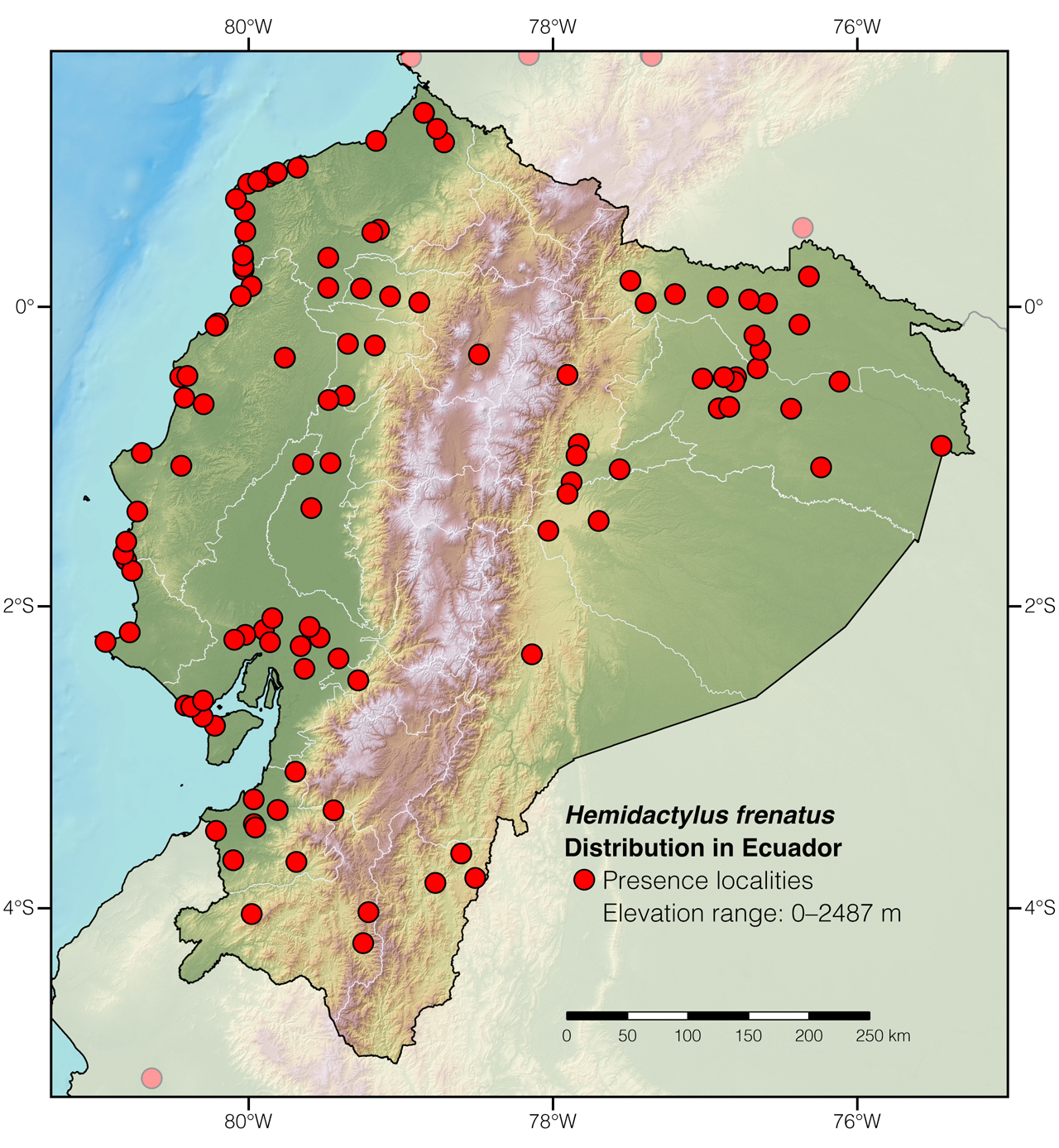

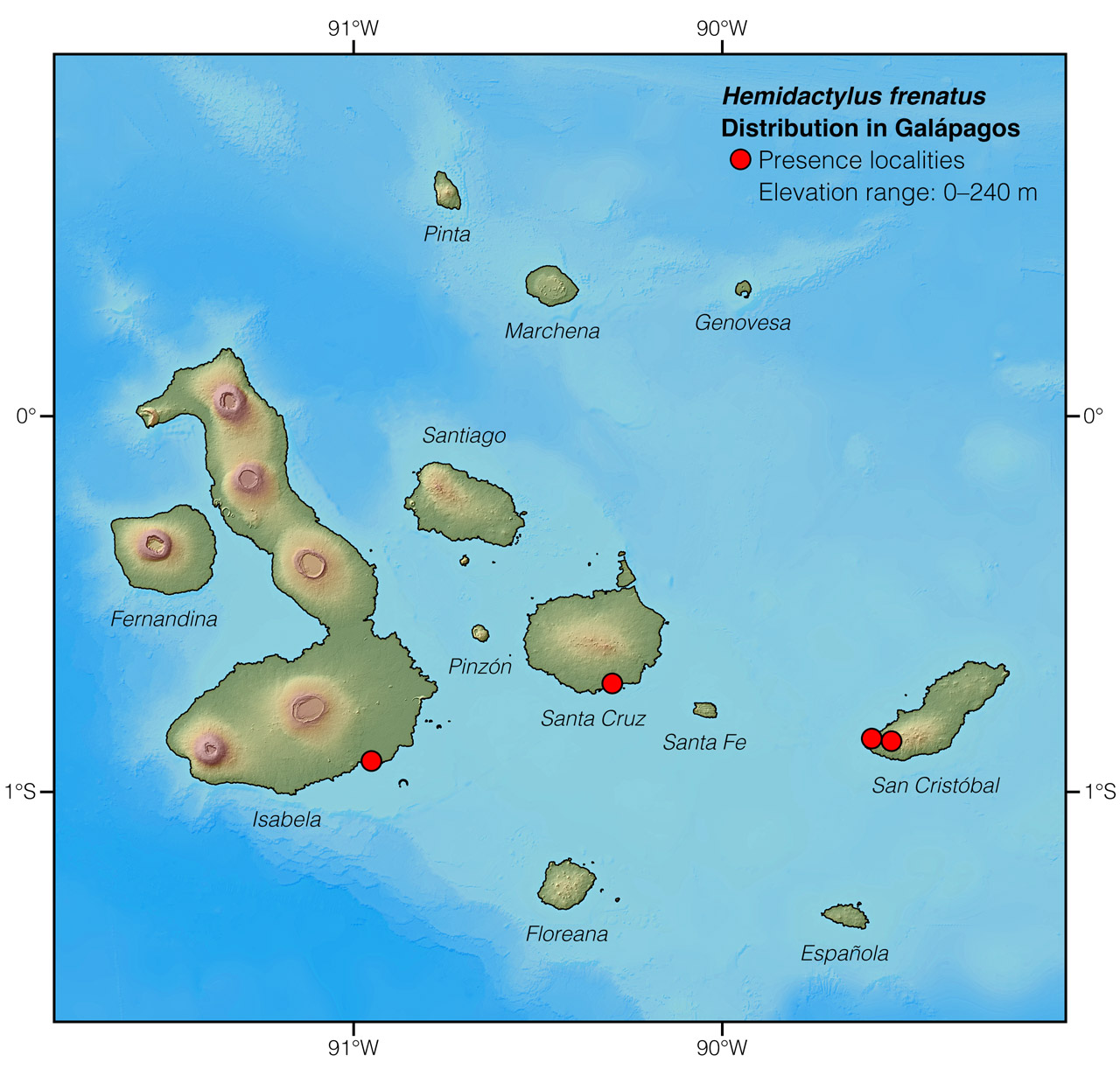

Distribution: Hemidactylus frenatus is native to Southeast Asia,36 but has been introduced to the Americas, Africa, Australia,26 and a number of tropical islands across the globe.12,26 In Ecuador, Common House-Geckos have become naturalized on more than 100 towns and cities (Fig. 2),44 including those in the Galápagos (Fig. 3).45

Figure 2: Distribution of Hemidactylus frenatus in mainland Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Hemidactylus frenatus in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Hemidactylus comes from the Greek words hemisys (=half) and daktylos (=finger).46 It probably refers to the rows of skin folds under these geckos’ digits,18 which are grouped in two halves. The specific epithet frenatus, which comes from the Latin frenum (=bridle) and the suffix -atus (=provided with),46 refers to the color pattern of the face.47

See it in the wild: Common House-Geckos can be seen year-round in and around buildings throughout their localities of occurrence in Ecuador. They have, for example, colonized the buildings of Yasuní Scientific Station. The best time to look for this species is just after sunset.

Special thanks to Laetitia Buscaylet for symbolically adopting the Common House-Gecko and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewers: Kenneth PetrencAffiliation: University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA. and Caty Frenkel

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2023) Common House-Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/YIZG6866

Literature cited:

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- von May R, Venegas PJ, Chávez G, Costa GC (2021) Range expansion of the invasive Tropical House Gecko, Hemidactylus mabouia (Squamata: Gekkonidae), in South America. Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 15: 323–334.

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Malkmus R, Manthey U, Vogel G, Hoffmann P, Kosuch J (2002) Amphibians and reptiles of Mount Kinabalu (North Borneo). Gantner Verlag, Ruggell, 424 pp.

- Frenkel C (2006) Hemidactylus frenatus (Squamata: Gekkonidae): call frequency, movement and condition of tail in Costa Rica. Revista de Biología Tropical 54: 1125–1130.

- Bustard HR (1970) Activity cycle of the tropical house gecko Hemidactylus frenatus. Copeia 1970: 173–176. DOI: 10.2307/1441987

- Synder GK, Weathers WW (1976) Physiological responses to temperature in the tropical lizard, Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria: Gekkonidae). Herpetologica 32: 252–257.

- Case TJ, Bolger DT, Petren K (1994) Invasions and competitive displacement among house geckos in the Tropical Pacific. Ecology 75: 464–477. DOI: 10.2307/1939550

- Cole NC, Jones CG, Harris S (2005) The need for enemy-free space: the impact of an invasive gecko on island endemics. Biological Conservation 125: 467–474. DOI: 10.1016/j.biocon.2005.04.017

- Marcellini DL (1970) Ethoecology of Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria, Gekkonidae) with emphasis on acoustic behavior. PhD thesis, Oklahoma, United States, University of Oklahoma.

- Werner YL (1990) Do gravid females of oviparous gekkonid lizards maintain elevated body temperatures? Hemidactylus frenatus and Lepidodactylus lugubris on Oahu. Amphibia-Reptilia 11: 200–204.

- Wogan G, Sumontha M, Phimmachak S, Lwin K, Neang T, Stuart BL, Thaksintham W, Caicedo JR, Rivas G, Tjaturadi B, Iskandar D (2021) Hemidactylus frenatus. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T99156022A1434103.en

- Petren K, Case TJ (1998) Habitat structure determines competition intensity and invasion success in gecko lizards. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 95: 11739–11744. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11739

- Keim LD (2002) Spatial distribution of the introduced Asian House Gecko across suburban/forest edges. PhD thesis, Brisbane, Australia, University of Queensland.

- Dutton R (1980) The herpetology of the Chagos archipelago. British Journal of Herpetology 6: 133–134.

- Henkel FW, Schmidt W (1995) Geckoes. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, 237 pp.

- Spawls S, Howell KM, Drewes RC, Ashe J (2001) A field guide to the reptiles of East Africa. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 544 pp.

- Grismer LL (2002) Amphibians and reptiles of Baja California. University of California Press, London, 96 pp.

- Tyler MJ (1961) On the diet and feeding habits of Hemidactylus frenatus (Duméril and Bibron) (Reptilia: Gekkonidae) at Rangoon, Burma. Transactions of The Royal Society of South Australia 84: 45–49.

- Díaz-Pérez J, Sampedro-Marín A, Ramírez-Pinilla M (2017) Actividad reproductiva y dieta de Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria: Gekkonidae) en el norte de Colombia. Papéis Avulsos De Zoologia 57: 459–472. DOI: 10.11606/0031-1049.2017.57.36

- Bolger DT, Case TJ (1992) Intra and interspecific interference behaviour among sexual and asexual geckos. Animal Behavior 44: 21–30. DOI: 10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80750-X

- McCoid MJ, Hensley RA (1993) Shifts in activity patterns in lizards. Herpetological Review 24: 87–88.

- Díaz JA, Dávila JA, Álvarez DM, Sampedro AC (2012) Dieta de Hemidactylus frenatus (Sauria: Gekkonidae) en un área urbana de la región Caribe colombiana. Acta Zoológica Mexicana 28: 613-616.

- Valencia JH, Garzón K (2011) Guía de anfibios y reptiles en ambientes cercanos a las estaciones del OCP. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 268 pp.

- Barquero MD, Hilje B (2005) House Wren preys on introduced gecko in Costa Rica. The Wilson Bulletin 117: 204–205. DOI: 10.1676/04-084

- Csurhes S, Markula A (2009) Pest animal risk assessment of the Asian House Gecko. Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries, Queensland, 20 pp.

- Domrow R (1992) Acari Prostigmata (excluding Trombiculidae) parasitic on Australian vertebrates: an annotated checklist, keys and bibliography. Invertebrate Taxonomy 4: 1283–1376. DOI: 10.1071/IT9901283

- Domrow R (1992) Acari Astigmata (excluding feather mites) parasitic on Australian vertebrates: an annotated checklist, keys and bibliography. Invertebrate Taxonomy 6: 1459–1606. DOI: 10.1071/IT9921459

- Jaing MH, Lin JY (1980) A study of the nematodes in the lizards, Japalura swinhonis formosensis and Hemidactylus frenatus. Biological bulletin, Department of Biology, College of Science, Tunghai University 53: 1–30.

- Barton DP (2007) Pentastomid parasites of the introduced Asian House Gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus (Gekkonidae), in Australia. Comparative Parasitology 74: 254–259. DOI: 10.1654/4209.1

- Marcelini DL (1974) Acoustic behavior of the gekkonid lizard, Hemidactylus frenatus. Herpetologica 30: 44–52.

- Frankenberg E, Marcellini DL (1990) Comparative analysis of the male multiple click calls of colonizing house geckos Hemidactylus turcicus from the southern U.S.A and Israel and Hemidactylus frenatus. Israel Journal of Zoology 37: 107–118. DOI: 10.1080/00212210.1990.10688646

- Murphy-Walker S, Haley SR (1995) Functional sperm storage duration in female Hemidactylus frenatus (Family Gekkonidae). Herpetologica 52: 365–373.

- Ota H (1994) Female reproductive cycles in the northernmost populations of the two gekkonid lizards, Hemidactylus frenatus and Lepidodactylus lugubris. Ecological Research 9: 121–130. DOI: 10.1007/BF02347487

- Hunsaker D (1966) Notes on the population expansion of the House Gecko, Hemidactylus frenatus. Philippine Journal of Science 95: 121–122.

- Lunney D, Peggy E, Hutchins P, Burgin S (2007) Pest or guest: The zoology of overabundance. Royal Zoological Society of New South Wales, Sydney, 270 pp.

- Perry G, Rodda GH, Fritts TH, Sharp TR (1998) The lizard fauna of Guam’s fringing islets: island biogeography, phylogenetic history, and conservation implications. Global Ecology and Biogeography 7: 353–365. DOI: 10.2307/2997683

- Greer AE (1989) The biology and evolution of Australian lizards. Surrey Beatty, Chipping Norton, 264 pp.

- Kraus F (2009) Alien reptiles and amphibians: a scientific compendium and analysis. Springer, New York, 563 pp.

- Brown S, Lebrun R, Yamasaki J, Ishii-Thoene D (2002) Indirect competition between a resident unisexual and an invading bisexual gecko. Behavior 139: 1161–1173.

- Petren K, Case TJ (1996) An experimental demonstration of exploitation competition in an ongoing invasion. Ecology 77: 118–132. DOI: 10.2307/2265661

- Rödder D, Solé M, Böhme W (2008) Predicting the potential distributions of two alien invasive house geckos (Gekkonidae: Hemidactylus frenatus, Hemidactylus mabouia). North-Western Journal of Zoology 4: 236–246.

- Canyon DV, Hii JLK (1997) The gecko: an environmentally friendly biological agent for mosquito control. Medical and Veterinary Entomology 11: 319–323.

- Jadin R, Altamirano MA, Yánez-Muñoz MH, Smith E (2009) First record of the common house gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus) in Ecuador. Applied Herpetology 6: 193–195. DOI: 10.15560/7.4.470

- Torres-Carvajal O, Tapia W (2011) First record of the common house gecko Hemidactylus frenatus Schlegel, 1836 and distribution extension of Phyllodactylus reissii Peters, 1862 in the Galápagos. Check List 7: 470–472. DOI: 10.15560/7.4.470

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron B (1836) Erpétologie générale, ou, Histoire naturelle complète des reptiles. Encyclopédique Roret, Paris, 430 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Hemidactylus frenatus in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Nariño | Barbacoas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Nariño | Corregimiento Remolino | Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala 2011 |

| Colombia | Nariño | El Remolino | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Nariño | Milagros | UPTC 2019 |

| Colombia | Nariño | Tumaco | Caicedo-Portilla & Dulcey-Cala 2011 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Bajo Mansoyá | GeoPark 3513; Cahueño & Barbosa 2022 |

| Ecuador | Azuay | Recinto Las Brisas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Cañar | El Chorro | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Huaquillas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Machala | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Palmales Nuevo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Pasaje | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | PetroEcuador La Victoria | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Piñas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Isabel, 18 km WSW of | CM 117837; VertNet |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Santa Rosa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Atacames | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bunche | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Castelnouvo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Durango | Torres-Carvajal & Salazar-Valenzuela 2012 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Esmeraldas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Hacienda Cucaracha | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Itapoa Reserve | Photo by Rául Nieto |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Las Peñas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Lote Rosero | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Mompiche | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Playa Escondida | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Quingüe | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Quinindé | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Same | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | Jadin et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tonsupa | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Tundaloma Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Eco Friendly hotel | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Progreso | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Hacienda La Soledad | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Ayora | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Villamil | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | USFQ station | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Alborada | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Cerro Blanco | Carvajal-Campos and Torres-Carvajal 2010 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Chongón | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Ciudad Celeste | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Comuna Bellavista | QCAZ 13217; Pazmiño Otamendi 2020 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Data de Posorja | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Empalme | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | El Triunfo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | General Villamil | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Ingenio San Carlos | Carvajal-Campos and Torres-Carvajal 2010 |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Isla Santay | Photo by Eduardo Zavala |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Milagro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Playas Villamil | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | PS Churute | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Puerto del Morro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Virgen de Fátima | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Loja | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Malacatos | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Loja | Mercadillo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Centro Científico Río Palenque | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Jauneche | Photo by Keyko Cruz |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Los Ángeles, 4 km W of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Los Ríos | Quevedo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Ayampe | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Bahía de Caráquez | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Canoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cocosolo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cojimíes | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Curia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Jama Campay | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Barquita | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Crespa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | La Mapara | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Manta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Muracumbo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Pedernales | Jadin et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Playa Nuestra | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Portoviejo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Puerto Cayo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Puerto López | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Punta Prieta | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Río Canoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Salinas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | QCAZ 16544; Pazmiño Otamendi 2020 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Archidona | Photo by Diego Piñán |

| Ecuador | Napo | Arosemena Tola | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Baeza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Puerto Barantilla | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Napo | Tena | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Campo SPF Río Yasuní | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Dayuma | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Edén | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Laguna Taracoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Nuevo Rocafuerte | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Pindo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Taracoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yarina Lodge | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuní Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Piatúa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano K32 | Dueñas et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Conocoto | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Hacienda El Paraíso | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Milpe Bird Sanctuary | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Puerto Quito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Punta Blanca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Salinas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | El Cisne | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Hotel Santo Domingo | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación Shuara | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Lago Agrio | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Palmeras Norte | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Recinto Amazonas, 2 km NE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Singue | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | San Pedro de los Cofanes | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Sevilla | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Shushufindi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Tarapoa | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Vicinity of Dureno | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Campamento Las Peñas | Dueñas et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | El Pangui | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Perú | Piura | Piura | iNaturalist; photo examined |