Published October 10, 2019. Updated November 14, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Gekkonidae | Lepidodactylus lugubris

English common names: Mourning Gecko, Maritime Gecko, Sad Gecko.

Spanish common names: Geco lúgubre, geco enlutado, salamanquesa lúgubre.

Recognition: ♂♂ 6.1cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=3.9 cm. ♀♀ 10.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=4.5 cm..1 The Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris) is the only gecko species in Ecuador that possesses the following combination of features: expanded digital disks, basal webbing between digits, and no enlarged scales on the body and tail (Fig. 1).2 This species may be confused with juveniles of H. frenatus and H. mabouia, but they can be distinguished by the presence of pointed tubercles along the tail.1,2

Figure 1: Individuals of Lepidodactylus lugubris from Puerto Ayora, Galápagos province, Ecuador.

Natural history: Lepidodactylus lugubris is a primarily nocturnal,1–3 gecko that occurs in high densities on walls and ceilings near electric lights, light posts, and palm trees.4–6 This gecko utilizes human-modified environments in a variety of lowland habitats, from deserts and rainforests, to plantations.7 During daylight, individuals hide within crevices, among dead leaves, under bark, or behind objects hung vertically.5,8 Their diet includes mostly insects that are attracted to artificial light sources,5,9 as well as spiders, amphipods, pill bugs, nectar, ripe fruit, jam, sugar, sweetened drinks, milk, and even their own eggs.10–12 Mourning Geckos are gregarious and communicate using sounds13 and head bobs.14 Lepidodactylus lugubris is parthenogenetic,15–17 an all-female species that reproduces in the absence of males. Nevertheless, there is female-female copulation,15 a behavior that stimulates both females to produce eggs. Clutches consist of two18–19 seawater-resistant20 adhesive5 eggs, produced throughout the year21 and deposited in communal nesting sites such as in crevices, holes, thatch of roofs, leaf axils, or under logs, bark, rocks, and palm fronds,5,22 with an incubation period of 65–103 days.19 While females occasionally produce male offspring, they are infertile.14 When threatened, individuals swiftly retreat into crevices or under surface objects. If captured, they easily shed the tail. Mourning Geckos are preyed upon by birds, mongooses, frogs, lizards (including Microlophus indefatigabilis and Hemidactylus frenatus), snakes, praying mantids, and spiders.5,23–25 They are also parasitized by worms.26

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..27 Listed in this category because the species thrives in human-modified environments,7 has increasing populations, and is invading new areas throughout the world.28

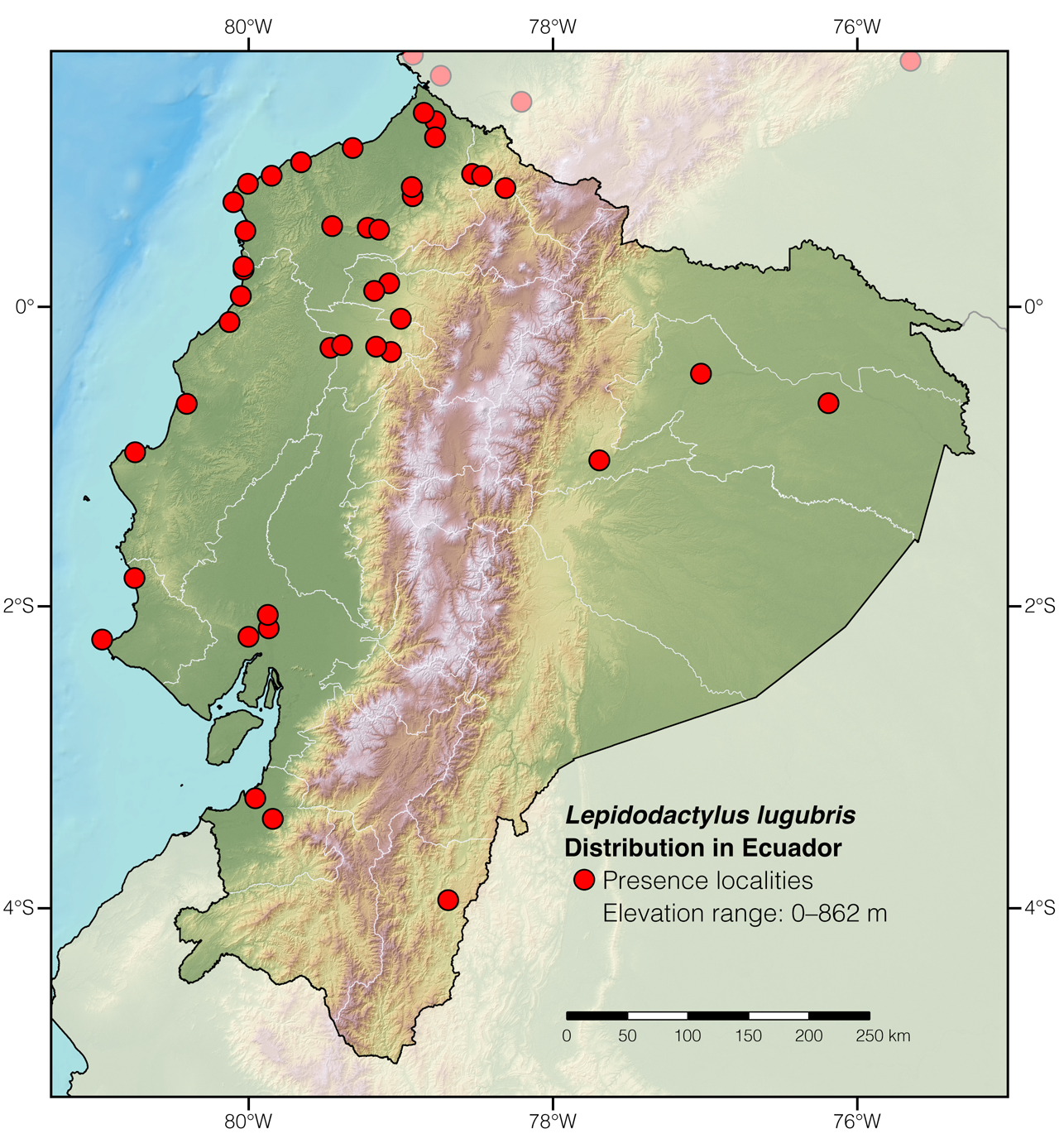

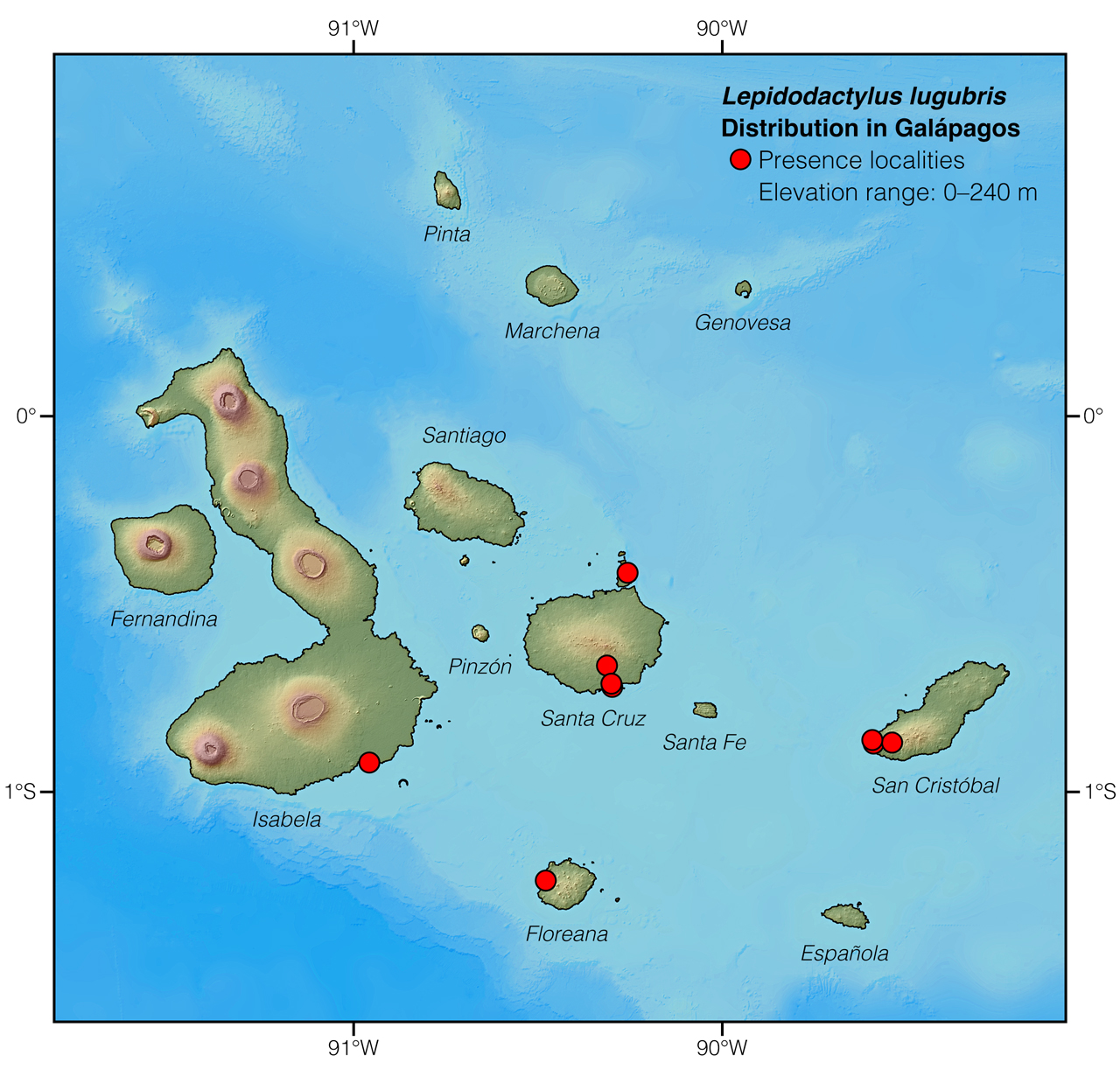

Distribution: Lepidodactylus lugubris is a cosmopolitan species native to Southeast Asia. It is introduced into the Americas, Australia, and a number of tropical islands across the globe. In Ecuador, the species has become naturalized across lowland areas (Fig. 2), including the Galápagos Islands (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Distribution of Lepidodactylus lugubris in mainland Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Lepidodactylus lugubris in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Lepidodactylus comes from the Greek lepis (=scale)29 and daktylos (=finger),29 and probably refers to the rows of scaly plates on the underside of the digits. The specific epithet lugubris is a Latin word meaning “mournful,”29 in reference to the unusual fact that only females were known at the time of description.30

See it in the wild: Mourning Geckos can be seen year-round in and around buildings throughout their localities of occurrence in Ecuador. They have, for example, colonized most buildings of the city Puerto Ayora in Galápagos. The best time to look for this species is just after sunset.

Special thanks to Billy Sveen for symbolically adopting the Mourning Gecko and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Authors: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasaminbAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Kenneth PetrencAffiliation: University of Cincinnati, Ohio, USA.

Photographer: Jose VieiradAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,eAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Guayasamin JM (2023) Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/HHLM5068

Literature cited:

- Savage JM (2002) The amphibians and reptiles of Costa Rica, a herpetofauna between two continents, between two seas. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 934 pp.

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Nafus MG (2012) Lepidodactylus lugubris. Foraging movement. Herpetological Review 43: 135.

- Malkmus R, Manthey U, Vogel G, Hoffmann P, Kosuch J (2002) Amphibians and reptiles of Mount Kinabalu (North Borneo). Gantner Verlag, Ruggell, 424 pp.

- Oliver JA, Shaw CE (1953) The amphibians and reptiles of the Hawaiian Islands. Zoologica 38: 65–95.

- Torres-Carvajal O, Tapia W (2011) First record of the common house gecko Hemidactylus frenatus Schlegel, 1836 and distribution extension of Phyllodactylus reissii Peters, 1862 in the Galápagos. Check List 7: 470–472. DOI: 10.15560/7.4.470

- Short KH, Petren K (2008) Boldness underlies foraging success of invasive Lepidodactylus lugubris geckos in the human landscape. Animal Behaviour 76: 429–437. DOI: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2008.04.008

- Brown WC, Parker F (1977) Lizards of the genus Lepidodactylus (Gekkonidae) from the Indo-Australian Archipelago and the islands of the Pacific, with description of new species. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 41: 253–260.

- Castro-Herrera F, Valencia A, Villaquirán D (2012) Diversidad de anfibios y reptiles del Parque Nacional Natural Isla Gorgona. Universidad del Valle, Cali, 112 pp.

- Hanley KA, Bolger DT, Case TJ (1994) Comparative ecology of sexual and asexual gecko species (Lepidodactylus) in French Polynesia. Evolutionary Ecology 8: 438–454. DOI: 10.1007/BF01238194

- Briggs AA, Young HS, McCauley DJ, Hathaway SA, Dirzo R, Fisher RN (2012) Effects of spatial subsidies and habitat structure on the foraging ecology and size of geckos. PLoS ONE 7: e41364. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0041364

- Miller MJ (1979) Oviphagia in the mourning gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris. Bulletin of the Chicago Herpetological Society 14: 117–118.

- Bosch RA, Páez RB (2017) First record from Cuba of the introduced mourning gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris (Duméril and Bibron, 1836). BioInvasions Records 3: 297–300. DOI: 10.3897/herpetozoa.33.e53625

- Brown SG, Murphy-Walker S (1996) Behavioral interactions between a rare male phenotype and female unisexual Lepidodactylus lugubris. Journal of Herpetology 6: 69–73.

- McCoid MJ, Hensley RA (1991) Pseudocopulation in Lepidodactylus lugubris. Herpetological Review 22: 8–9.

- Cuellar O, Kluge AG (1972) Natural parthenogenesis in the gekkonid lizard Lepidodactylus lugubris. Journal of Genetics 61: 14–26. DOI: 10.1007/BF02984098

- Orozco-Cardona M (1996) Ciclo reproductivo de Lepidodactylus lugubris (Sauria Gekkonidae). BSc Thesis, Cali, Universidad del Valle.

- Brown SG, Sakai TJY (2010) Social experience and egg development in the parthenogenic gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris. Ethology 79: 317–323. DOI: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.1988.tb00720.x

- Griffing AH, Sanger TJ, Matamoros IC, Nielsen SV, Gamble T (2018) Protocols for husbandry and embryo collection of a parthenogenetic gecko, Lepidodactylus lugubris (Squamata: Gekkonidae). Herpetological Review 49: 230–235.

- Brown SG, Duffy PK (1992) The effects of egg-laying site, temperature, and salt-water on incubation time and hatching success in the gecko Lepidodactylus lugubris. Journal of Herpetology 26: 510–513. DOI: 10.2307/1565135

- Ota H (1994) Female reproductive cycles in the northernmost populations of the two gekkonid lizards, Hemidactylus frenatus and Lepidodactylus lugubris. Ecological Research 9: 121–130. DOI: 10.1007/BF02347487

- Manthey U, Grossmann W (1997) Amphibien und Reptilien Südostasiens. Natur und Tier-Verlag, Münster, 512 pp.

- McCoid MJ, Hensley RA (1993) Shifts in activity patterns in lizards. Herpetological Review 24: 87–88.

- Darevsky IS (1964) Two new species of gekkonid lizards from the Komodo Island in the Lesser Sundas Archipelago. Zoologischer Anzeiger 173: 169–174.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Goldberg SR, Bursey CR, Cheam H (1998) Gastrointestinal helminths of four gekkonid lizards, Gehyra mutilata, Gehyra oceanica, Hemidactylus frenatus and Lepidodactylus lugubris from the Mariana Islands, Micronesia. The Journal of Parasitology 84: 1295–1298.

- Diesmos AC, Hamilton A, Allison A, Tallowin O, Tala C, Victoriano P, Ortiz JC, Nunez H, Garin C, Vidal M, McGuire J, Iskandar D, Avila-Pires TCS, Aparicio J, Oliver P, Perez P, Shang G (2021) Lepidodactylus lugubris. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-3.RLTS.T172593A1348302.en

- Olmedo J, Cayot L (1994) Introduced geckos in the towns of Santa Cruz, San Cristóbal and Isabela. Noticias de Galápagos 53: 7–12.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Duméril AMC, Bibron B (1836) Erpétologie générale, ou, Histoire naturelle complète des reptiles. Encyclopédique Roret, Paris, 430 pp. DOI: 10.5962/bhl.title.45973

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Lepidodactylus lugubris in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Colombia | Nariño | Bajo Cumilinche | UPTC 2019 |

| Colombia | Nariño | El Mira | Calderon et al. 2023 |

| Colombia | Nariño | La Guayacana | Calderon et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Machala | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | El Oro | Río Negro | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Atacames | MHNG 2437.093; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Bosque Protector La Chiquita | MCZ 149674; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Caimito | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Canandé Biological Reserve | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2005 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Carondelet | MHNG 2460.089; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Chuchubi | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Esmeraldas | Fugler 1966 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Itapoa Reserve | Photo by Rául Nieto |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | La Boca | MHNG 2356.046; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Mompiche | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Montalvo | MHNG 2437.092; collection database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Playa Escondida | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San José de Cayapas | Yánez-Muñoz et al. 2010 |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | San Lorenzo | MCZ 166524; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Esmeraldas | Zapallo Grande | MHNG 2460.089; collection database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Baltra airport | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Bellavista | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Eco Friendly hotel | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | El Progreso | Cisneros-Heredia et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa de los Alemanes | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Mann | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Ayora | Hoogmoed 1989 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Velasco Ibarra | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Villamil | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Guayaquil, Plaza del Rosal | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | La Aurora | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Guayas | Terranostra | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Carolina | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Imbabura | Lita | MHNG 2529.087; collection database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Cocosolo | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | El Carmen | Cuadrado Saldarriaga 2020 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Juananu | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Manta | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Olón | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Pedernales | Arteaga et al. 2013 |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Saiananda | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Manabí | Three Forests Trail | Photo by Paul Maier |

| Ecuador | Napo | El Jardín Alemán | Guerra-Correa 2017 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | El Coca | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Tiputini Biodiversity Station | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Centro Tecnológico Ganaderos Orenses | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | La Celica | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Pichincha | Rancho Suamox | Photo by Rafael Ferro |

| Ecuador | Santa Elena | Salinas | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Hostería Tinalandia | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Rancho Santa Teresita | USNM 283525; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Santo Domingo de los Tsáchilas | Santo Domingo de los Colorados | MCZ 166564; VertNet |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Paquisha | iNaturalist; photo examined |