Published October 10, 2019. Updated December 22, 2023. Open access. Peer-reviewed. | Purchase book ❯ |

Floreana Leaf-toed Gecko (Phyllodactylus baurii)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Phyllodactylidae | Phyllodactylus baurii

English common names: Floreana Leaf-toed Gecko, Baur’s Leaf-toed Gecko.

Spanish common names: Geco de Floreana, geco de Baur.

Recognition: ♂♂ 8.3 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 8.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1 Phyllodactylus baurii is easily distinguishable from other native saurians occurring on Floreana Island (that is, iguanas and lava lizards) by its nocturnal habits, vertical pupils, and fingertips lacking visible claws.1 The dorsal coloration is usually pale grayish brown with faint irregular dark blotches and scattered white spots (Fig. 1).1 Phyllodactylus baurii is generally the only gecko in its area of distribution, but it coexists with the Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris) in urban areas of Floreana Island. It differs from this invasive gecko by its rounded, instead of expanded, digital disks.1

Figure 1: Individuals of Phyllodactylus baurii from Galápagos: Gardner Islet (); Puerto Velazco Ibarra, Floreana Island ().

Natural history: Phyllodactylus baurii is a nocturnal and mostly terrestrial gecko that occurs in areas of dry shrubland, caves, and rural gardens.1–3 Floreana Leaf-toed Geckos forage on rocky outcrops, soil, and twigs up to 1.7 m above the ground, and they are active on dry or drizzly nights.1 They also utilize walls and ceilings of buildings near thickets of vegetation. During the daytime, the geckos seek refuge under lava blocks, dry wood, and in cracks in the rocks.3 When threatened, their typical response is to flee into crevices. If captured, they may shed the tail and emit high-pitched release sounds.1,3 The species is probably entirely insectivorous, but so far only cockroaches1 have been reported as prey items. Females lay eggs under lava blocks3 and the clutch size is probably 1–2 eggs. The Eastern Galápagos Racer (Pseudalsophis biserialis) has been confirmed as a predator of P. baurii.4

Conservation: Near Threatened Not currently at risk of extinction, but requires some level of management to maintain healthy populations..1 Phyllodactylus baurii is listed in this category because the species has a restricted distribution and is facing both predation by housecats and displacement by the invasive Mourning Gecko (Lepidodactylus lugubris). Therefore, it may qualify for a threatened category in the near future if these threats are not addressed. However, there is no current information on the population trend of the Floreana Leaf-toed Gecko to determine whether its numbers are declining.

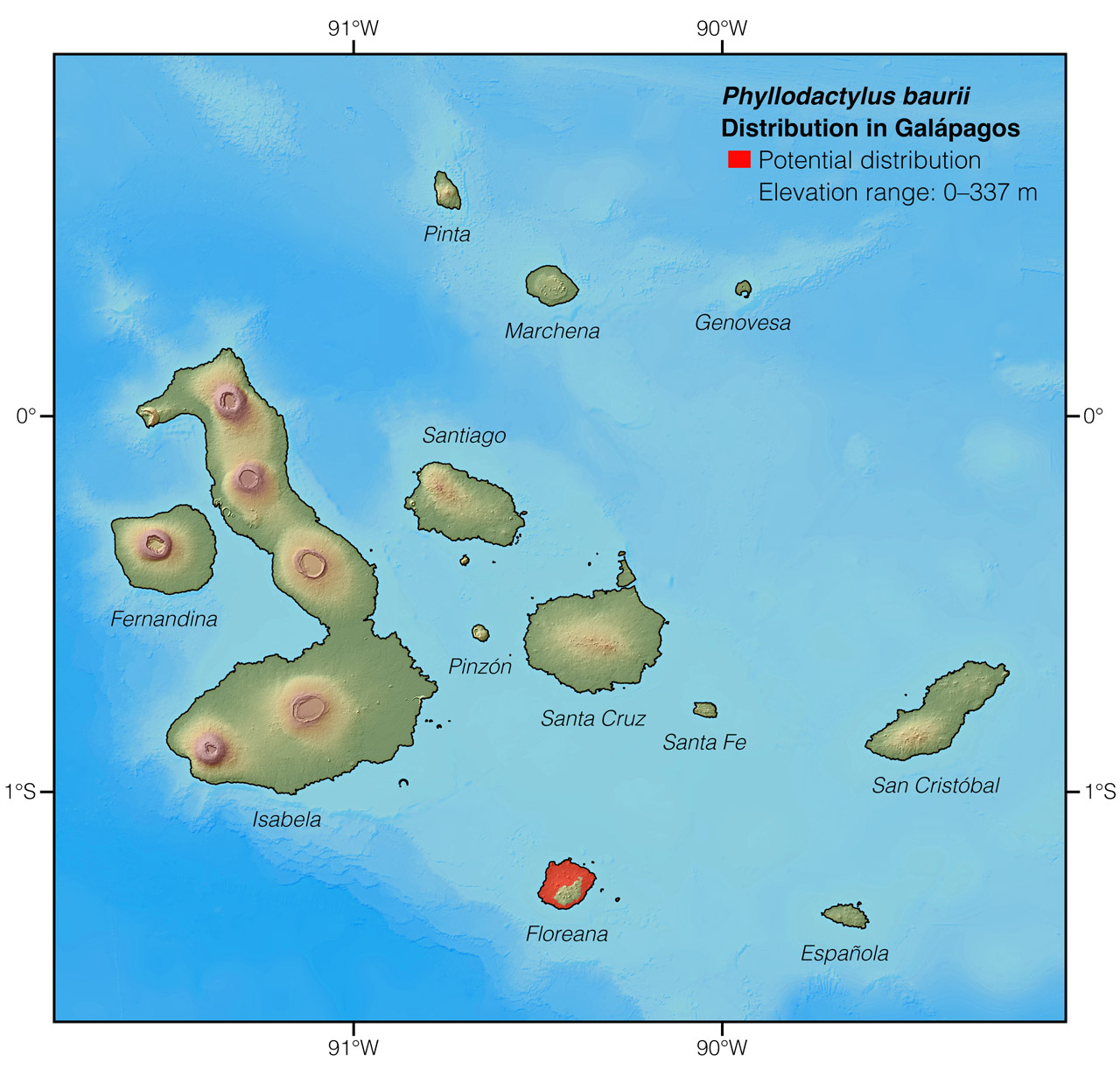

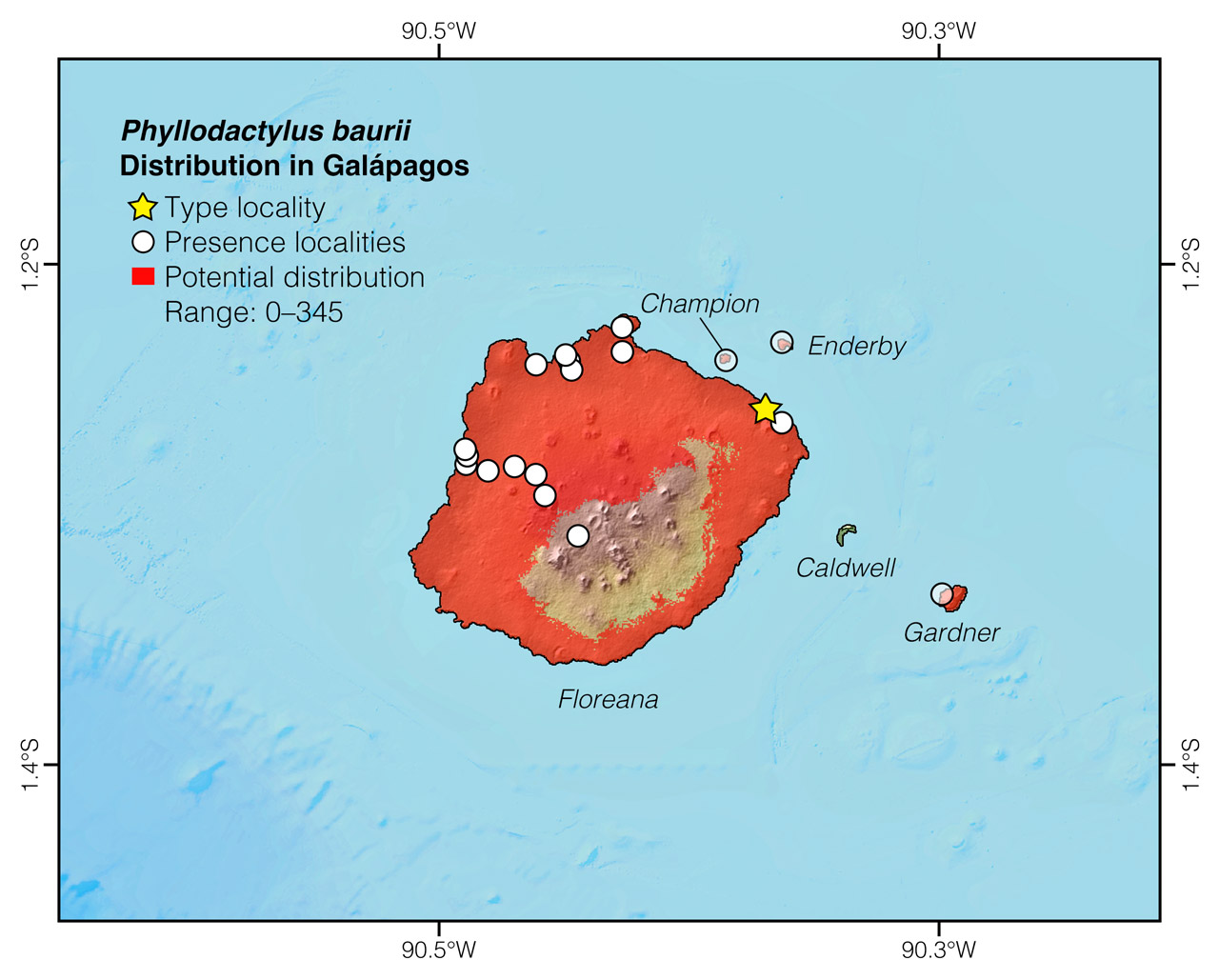

Distribution: Phyllodactylus baurii is endemic to an area of approximately 132 km2 on Floreana Island and its surrounding islets Champion, Enderby, and Gardner (Figs 2, 3), Galápagos, Ecuador.

Figure 2: Distribution of Phyllodactylus baurii in Galápagos. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Figure 3: Distribution of Phyllodactylus baurii in Floreana Island. The star corresponds to the type locality: Las Cuevas. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Phyllodactylus comes from the Greek words phyllon (=leaf) and daktylos (=finger),5 and refers to the leaf-shaped fingers characteristic of this group of geckos. The specific epithet baurii honors Georg Baur, a vertebrate paleontologist who studied reptiles in the Galápagos Islands.6 Baur postulated that the Galápagos Islands were remnant mountain peaks resulting from the submergence of a former continental landmass.6

See it in the wild: Individuals of Phyllodactylus baurii are considered a guaranteed sighting during any herpetological night hike in the outskirts of the town Puerto Velasco Ibarra. The best time to look for geckos of this species is just after sunset, when they are actively foraging on rocky surfaces.

Authors: Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. Gabriela Aguiar,bIndependent researcher, Quito, Ecuador. and Juan M GuayasamincAffiliation: Universidad San Francisco de Quito, Quito, Ecuador.

Academic reviewer: Cruz MárquezdAffiliation: University of Rome Tor Vergata, Rome, Italy.

Photographers: Alejandro Arteaga,aAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador. Jose Vieira,eAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,fAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Frank PichardoeAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A, Aguiar G, Guayasamin JM (2023) Floreana Leaf-toed Gecko (Phyllodactylus baurii). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/JQGR3968

Literature cited:

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J, Tapia W, Guayasamin JM (2019) Reptiles of the Galápagos: life on the Enchanted Islands. Tropical Herping, Quito, 208 pp. DOI: 10.47051/AQJU7348

- Steadman DW (1986) Holocene vertebrate fossils from Isla Floreana, Galápagos. Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology 413: 1–103. DOI: 10.5479/SI.00810282.413

- Van Denburgh J (1912) Expedition of the California Academy of Sciences to the Galápagos Islands, 1905-1906. VI. The geckos of the Galápagos Archipelago. Proceedings of the California Academy of Sciences 1: 405–430.

- Christian EJ (2017) Demography and conservation of the Floreana racer (Pseudalsophis biserialis biserialis) on Gardner-by-Floreana and Champion islets, Galápagos Islands, Ecuador. PhD thesis, Auckland, New Zealand, Massey University.

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington, 882 pp.

- Garman S (1892) The reptiles of the Galápagos Islands. Bulletin of the Essex Institute 24: 73–87.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Phyllodactylus baurii in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Asilo de la Paz | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Barn Owl Cave | Steadman 1986 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Black beach road | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Champion islet | Steadman 1982 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Enderby islet | Steadman 1982 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Finch Cave | Steadman 1986 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Floreana Lava Lodge | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Gardner islet | Steadman 1982 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | La Paz, 2.5 km NW of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Las Cuevas* | Garman 1892 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Playa Negra | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Post Office bay | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Flores | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Velasco Ibarra | Torres-Carvajal et al. 2014 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Velasco Ibarra, 1 km SE of | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Puerto Velasco Ibarra, 3 km SE of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Ayora, 2 km NW of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Cormorán | Arteaga et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Galápagos | Punta Cormorán, 1 km S of | Arteaga et al. 2019 |