Published March 16, 2021. Updated May 17, 2024. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Amazon Coffee-Snake (Ninia hudsoni)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Colubridae | Ninia hudsoni

English common names: Amazon Coffee-Snake, Hudson’s Coffee Snake, Guiana Coffee-Snake.

Spanish common names: Culebra cafetera amazónica, viejita amazónica, serpiente de Hudson.

Recognition: ♂♂ 49.4 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 42.7 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=33.8 cm..1 Ninia hudsoni can be distinguished from other snakes by having a strong white nuchal band that covers the parietal scales and part of the frontal scale. In some specimens, the white nuchal band can reach the last supralabial scales (sixth or seventh). Typically, Ninia hudsoni exhibits blackish dorsal surfaces, strongly-keeled dorsal scales, and immaculate white ventral surfaces, except the posterior half of the tail, which is brown-dusted.2,3 However, there are records of albinism in this species,3 in which individuals exhibit a cream rosaceous dorsal coloration. Individuals of N. hudsoni are the largest among South American coffee snakes, as well as those having the most conspicuous and extended nuchal band. Among Ecuadorian snakes, Atractus occipitoalbus resembles N. hudsoni; however, this snake can be distinguished by having smooth dorsal scales and dark ventral surfaces.4

Figure 1: Individuals of Ninia hudsoni from Tamandúa Reserve, Pastaza province, Ecuador. j=juvenile.

Natural history: Ninia hudsoni is a terrestrial, semi-fossorial, and nocturnal snake with occasional diurnal and crepuscular activity.5,6 This species inhabits both well-preserved evergreen forests as well as transformed habitats such as plantations, pastures, and rural gardens.5,6 Individuals are usually found active on the forest floor during the night, but some have been found hidden under fallen palm fronds during the day.4 They are harmless and docile snakes. However, during handling, individuals can exhibit anti-predator behaviors such as hiding the head under body coils, crouching, and cloacal discharges. Currently, basic biological features such as diet, reproductive cycle, and ecological interactions remain largely unknown for this species. A female from Sumaco Volcano, Ecuador, laid a clutch of 2 eggs that hatched after a 3-month incubation period.7 There are records of Amazon Coffee-Snakes being preyed upon by other snakes, including by Micrurus ortoni8 and by a juvenile of Clelia clelia.9 It is expected that, like its congeners, N. hudsoni probably feeds on snails, slugs, earthworms, and leeches.10,11

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..12,13 Ninia hudsoni is listed in this category because, although few populations are known,5 the species has a broad distribution that includes many protected areas and it persists in human-modified habitats.12 Currently, there are no major widespread threats affecting the long-term survival of the species. The most important localized threats to some populations of N. hudsoni is forest destruction due to the expansion of the agricultural frontier, the construction of roads through pristine habitats, large-scale mining, and hydroelectric projects.

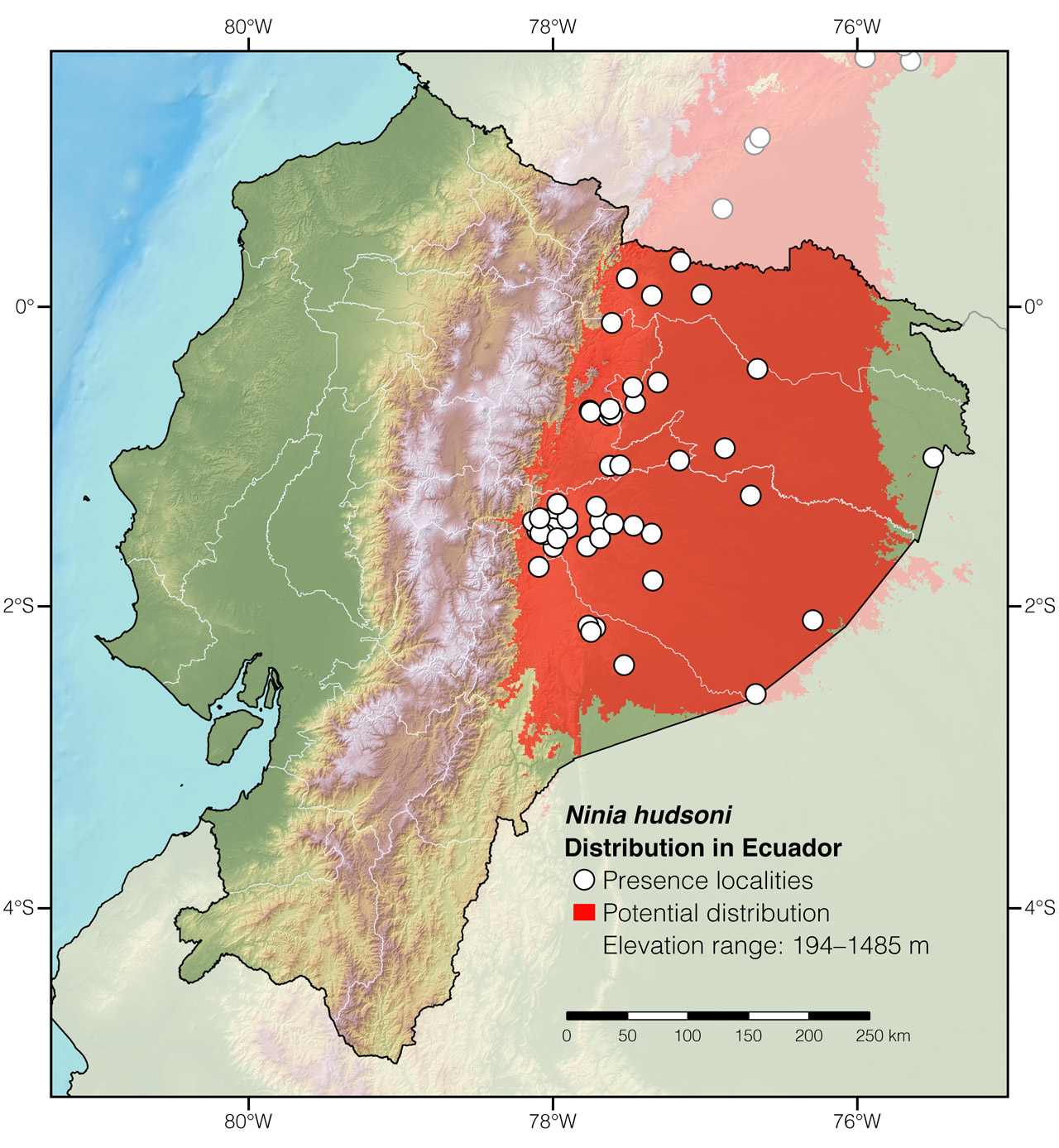

Distribution: Ninia hudsoni has a broad (~2,714,110 km2) distribution throughout the Amazon Basin, from southern Colombia and Ecuador (Fig. 2) to northern Bolivia and eastward to Central Brazil. This species seems to be restricted to the north, south, and west edges of the Amazon basin.5

Figure 2: Distribution of Ninia hudsoni in Ecuador. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Ninia was coined by Baird and Girard in 1853 without any reference regarding its Greek or Latin root. However, Ninia was one of the many names in Greek mythology used to refer to Eurydice, wife of Orpheus, a legendary musician, poet, and prophet. According to the myth, Eurydice dies after her wedding by stepping on a viper. Orpheus goes mad by losing his only love and travels to the underworld to retrieve her. He plays his softened music so extraordinarily that Hades (God of death) and Persephone (Queen of death) allow him to take Eurydice back to the world of the living.14 As far as is known, Ninia does not have Latin roots. The specific epithet hudsoni honors C. A. Hudson, who collected the holotype of the species in the late 1930s and is best known for his entomology collections deposited in the British Museum of Natural History.15

See it in the wild: Ninia hudsoni seems to be naturally rare throughout much of its distribution, but in some areas of Ecuador (especially Narupa Reserve and Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary), snakes of this species can be seen at least once every week. They are easier to spot at night by scanning the leaf-litter along forested trails. During the day, individuals can be encountered by sampling leaf-litter or by turning over surface objects in pastures near the forest border.

Authors: Teddy Angarita-SierraaAffiliation: Yoluka ONG, Fundación de Investigación en Biodiversidad y Conservación, Bogotá, Colombia.,bAffiliation: Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Universidad Manuela Beltrán, Bogotá, Colombia. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

Photographer: Frank PichardocAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Angarita-Sierra T, Arteaga A (2024) Amazon Coffee-Snake (Ninia hudsoni). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/CTUE6496

Literature cited:

- Camper JD (2015) Ninia hudsoni (Hudson’s Coffee Snake). Maximum size. Herpetological Review 46: 452–453.

- Parker HW (1940) Undescribed anatomical structures and new species of reptiles and amphibians. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 11: 270–271.

- Valencia JH, Alcoser-Villagómez M, Garzón K, Holmes D (2009) Albinism in Ninia hudsoni Parker, 1940 from Ecuador. Herpetozoa 21: 190–192.

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- de Avelar São-Pedro V, de Freitas MA, de Oliveira EF, Mendes Venâncio N, Pinheiro Zanotti A (2016) Geographical distribution of Ninia hudsoni (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) with new occurrence records. Oecologia Australis 20: 537–542. DOI: 10.4257/oeco.2016.2004.14

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Jeff Camper, pers. comm.

- Rojas-Morales JA, Cabrera-Vargas FA, Ruiz-Valderrama DH (2018) Ninia hudsoni (Serpentes: Dipsadidae) as prey of the coral snake Micrurus hemprichii ortonii (Serpentes: Elapidae) in northwestern Amazonia. Boletín Científico Museo de Historia Natural, Universidad de Caldas 22: 102–105. DOI: 10.17151/bccm.2018.22.1.9

- Wright T, Floyd E, Camper JD, Nilsson J (2019) Clelia clelia (Black Mussurana). Diet. Herpetological Review 50: 388–387.

- Angarita-Sierra T, Lozano–Daza SA (2019) Life is uncertain, eat dessert first: feeding ecology and prey-predator interactions of the coffee snake Ninia atrata. Journal of Natural History 53: 1401–1420. DOI: 10.1080/00222933.2019.1655105

- Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Guayasamin JM (2013) The amphibians and reptiles of Mindo. Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica, Quito, 257 pp.

- Catenazzi A, Cisneros-Heredia DF, Gagliardi G, Nogueira C (2019) Ninia hudsoni. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T203550A2768349.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- Bowra CM (1952) Orpheus and Eurydice. Dancing Times 2: 113–126.

- Beolens B, Watkins M, Grayson M (2011) The eponym dictionary of reptiles. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 296 pp.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Ninia hudsoni in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Cerro El Aguacate | SINCHI 991 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Florencia | Rojas-Morales et al. 2018 |

| Colombia | Caquetá | Vereda el Paraíso | ICN 10516 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Centro Experimental Amazónico | Betancourth-Cundar & Gutiérrez 2010 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Finca Mariposa | ICN 7130 |

| Colombia | Putumayo | Orito | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Loreto | Ávila Viejo | São-Pedro et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Arutam | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Taisha | Valencia et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Wisui | Chaparro et al. 2011 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guamaní | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hidroeléctrica Coca Codo Sinclair | COCASINCLAIR 2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Huaorani Lodge | Photo by Etienne Littlefair |

| Ecuador | Napo | Jatun Sacha Biological Station | Vigle 2008 |

| Ecuador | Napo | La Cruz Blanca | MCZ 171871 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Narupa Reserve | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco | MZUTI 5551 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Hollín | São-Pedro et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Runa Huasi | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wawa Sumaco | Camper et al. (in press) |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | This work |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Jatuncocha | USNM 232956 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Río Bigal Biological Reserve | Photo by Thierry García |

| Ecuador | Orellana | San José de Payamino | Photo by Ross Maynard |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Alto Río Curaray | São-Pedro et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Andoas | AMNH 49073 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Arajuno | São-Pedro et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bataburo Lodge | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Bellavista | Angarita-Sierra 2014 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Cabeceras del Bobonaza | USNM 232961 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Canelos | USNM 232958 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Centro Fátima | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Centro Shuar Amazonas | Valencia et al. 2009 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera, 4 km SE of | KU 121337 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera, 5 km NW of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Moretecocha | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Palora, 11 km W of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Puyo, 1 km W of | KU 127133 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Anzu Reserve | MECN 2013 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Arajuno, headwaters of | USNM 232963 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Conambo | USNM 232966 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Lliquino | USNM 232967 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Rutuno | USNM 232969 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Villano | Angarita-Sierra 2014 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | MHNG 2398.056 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay In Situ | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tamandúa | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tamandúa Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tambo Unión | MCZ 157152 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Villano B | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Comuna Shuar Chari | Nogueira et al. 2019 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Estación Cayagama | Valencia & Garzón 2011 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limoncocha | UIMNH 61220 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Libre | KU 121913 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | São-Pedro et al. 2016 |