Published October 26, 2021. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Cloudy Coralsnake (Micrurus steindachneri)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Serpentes | Elapidae | Micrurus | Micrurus steindachneri

English common names: Cloudy Coralsnake, Steindachner’s Coralsnake.

Spanish common names: Coral nebulosa, coral de Steindachner, coral de laderas.

Recognition: ♂♂ 88.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. ♀♀ 104.2 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail..1 In Ecuador, the majority of true coralsnakes (genus Micrurus) can be distinguished from most, but not all, false coral snakes by having brightly colored rings that encircle the body (rings evident on the belly), small eyes that are about the same size as the post-ocular scales, and no loreal scale.1,2 In the Amazonian foothills of the Andes of Ecuador, M. steindachneri is one of two species in the genus having black rings arranged in monads, rather than in triads (Fig. 1).1 The other snake is M. ornatissimus, which has black and red rings of similar width, instead of red rings wider than the black rings.1 Erythrolamprus guentheri is a false coralsnake that mimics M. steindachneri (a case of BatesianA harmless species imitates the warning coloration of a venomous one. mimicry), but its eyes are considerably (6.4–6.6 times) larger than the adjacent preocular scales, whereas in coralsnakes the eye is about the same size as the preocular scale.

Figure 1: Individuals of Micrurus steindachneri from Amazonian Ecuador: El Chaco, Napo province (); Campamento Fruta del Norte, Morona Santiago province ().

Natural history: Micrurus steindachneri is a rarely seen terrestrial to semi-fossorial snake that inhabits pristine rainforests and occasionally ventures into clearings, pastures, plantations, and rural gardens.1,3 Cloudy Coralsnakes have been seen active on soil, in puddles, or among leaf-litter during the day or at night, especially after heavy rains.1,3 They actively forage in search of prey, which includes snakes (M. ornatissimus)1 and lizards (Alopoglossus brevifrontalis).4 The warning coloration is the primary defense mechanism of M. steindachneri. Individuals are usually calm and try to flee when threatened. If disturbed, they engage in complex and seemingly erratic behavior: they hide the head beneath body coils, crawl spasmodically forward and then backward, and display their bright tails as a decoy.1,3 They are also capable of striking if provoked. Their venom is neurotoxic and is probably lethal to humans, but only one published record of envenomation exist. A 46-year-old woman developed mild symptoms after being bitten. These included persistent pain and swelling.2 Although the real clutch size in this species is not known, a gravid female from Tungurahua province, Ecuador, contained nine eggs.1

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..5,6 Micrurus steindachneri is listed in this category because the species has a wide distribution spanning many protected areas. Furthermore, approximately 72% of the species’ extent of occurrence overlaps with pristine habitats.7 The most important threat to the long-term survival of the species is habitat destruction mostly due to mining and the expansion of the agricultural frontier. Vehicular traffic and human persecution are also sources of mortality to individuals of this species.3,8,9

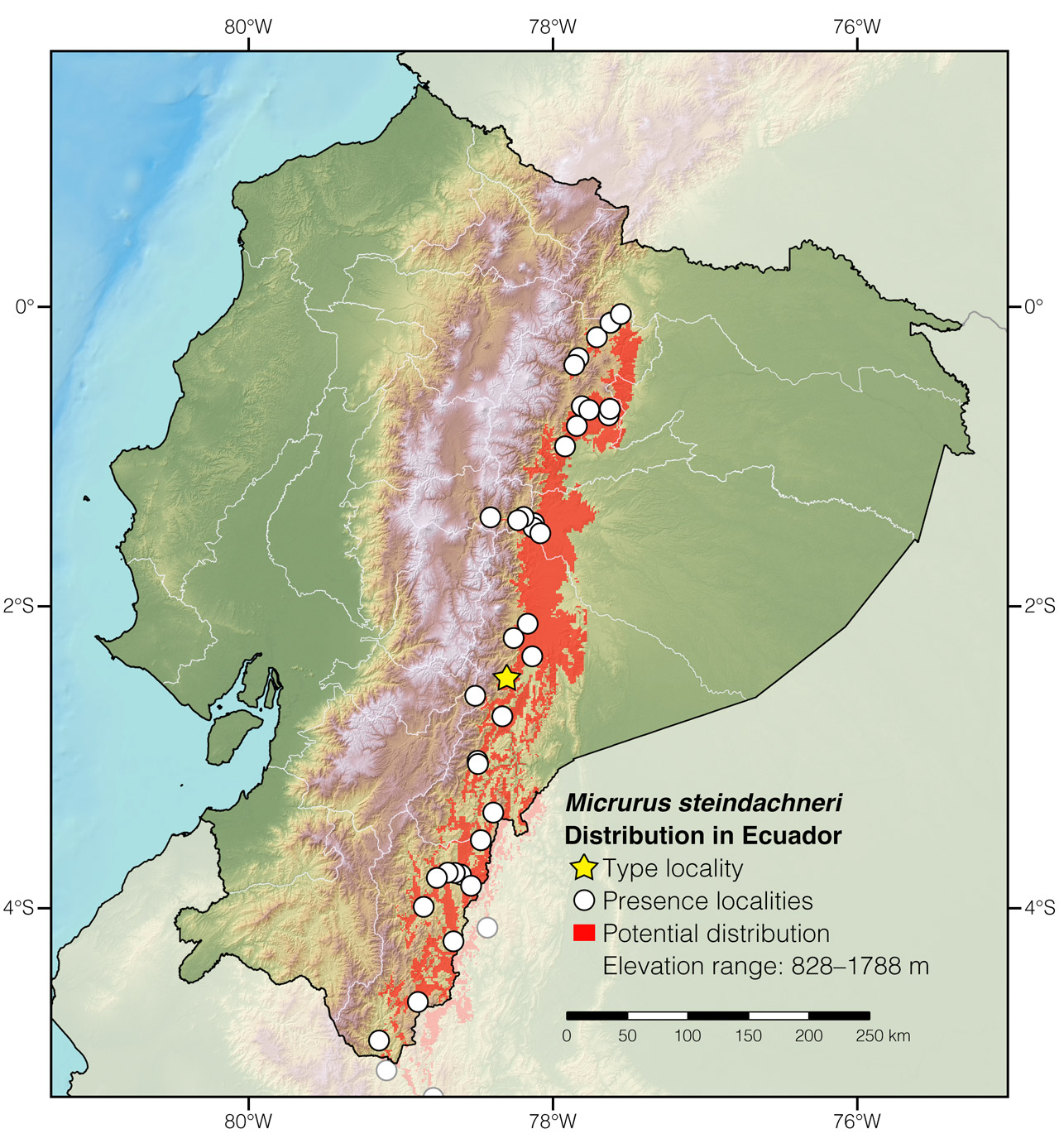

Distribution: Micrurus steindachneri is native to the Amazonian slopes of the Andes in Ecuador (Fig. 2) and Perú.

Figure 2: Distribution of Micrurus steindachneri in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the approximate general type locality: between Macas and Méndez. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The name Micrurus is derived from the Greek words mikros (=small) and oura (=tail), referring to the short tail in members of this group.2 The specific epithet steindachneri honors Austrian herpetologist and ichthyologist Franz Steindachner (1834–1919), director of the Naturhistorisches Museum in Vienna.2

See it in the wild: Cloudy Coralsnakes can be found at a rate of about once every few months. They seem to be particularly abundant in Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary and around the town of El Chaco, where these snakes are typically found around sunset along forest trails or roads.

Special thanks to Remon ter Harmsel for symbolically adopting the Cloudy Coralsnake and helping bring the Reptiles of Ecuador book project to life.

Click here to adopt a species.

Author: Alejandro ArteagaaAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographer: Jose VieirabAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,cAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador.

How to cite? Arteaga A (2021) Cloudy Coralsnake (Micrurus steindachneri). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/PVWD8819

Literature cited:

- Valencia JH, Garzón-Tello K, Barragán-Paladines ME (2016) Serpientes venenosas del Ecuador: sistemática, taxonomía, historial natural, conservación, envenenamiento y aspectos antropológicos. Fundación Herpetológica Gustavo Orcés, Quito, 653 pp.

- Campbell JA, Lamar WW (2004) The venomous reptiles of the western hemisphere. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 774 pp.

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Lee JL, Hernández-Morales C, McDiarmid RW (2018) First report on the reproductive biology and diet of two coral snake species (Micrurus) from the western Amazon of Perú and Ecuador (Serpentes: Elapidae) using x-radiography. Herpetology Notes 11: 409–412.

- Valencia J, Sánchez J (2017) Micrurus steindachneri. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T50951888A50951937.en

- Reyes-Puig C (2015) Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador. MSc thesis, Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador, 73 pp.

- MAE (2012) Línea base de deforestación del Ecuador continental. Ministerio del Ambiente del Ecuador, Quito, 30 pp.

- Camper JD, Torres-Carvajal O, Ron SR, Nilsson J, Arteaga A, Knowles TW, Arbogast BS (2021) Amphibians and reptiles of Wildsumaco Wildlife Sanctuary, Napo Province, Ecuador. Check List 17: 729–751.

- Urgilés VL, Sánchez JC, Astudillo PX (2016) Registro de la serpiente coral de Steindachneri Micrurus steindachneri (Squamata: Elapidae) en el Área Ecológica de Conservación Municipal Tinajillas-Río Gualaceño. Avances en Ciencias e Ingeniería 8: 82–85. DOI: 10.18272/aci.v8i14.462

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Micrurus steindachneri in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | AECM Tinajillas-Río Gualaceño | Urgilés et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Alto Río Upano | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Cabeceras del Río Piuntza | Reynolds 1997 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Campamento Fruta del Norte | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Guarumales | Photo by Ernesto Arbeláez |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Méndez | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Parque Nacional Sangay | Brito & Almendariz 2013 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Plan de Milagro, 1 mile S of | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Cascada de San Rafael | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | El Chaco | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Estación de bombeo El Salado | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Guamaní | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Narupa Reserve (higher trails) | This work |

| Ecuador | Napo | Narupa Reserve (lower trails) | Photo by Francisco Sornoza |

| Ecuador | Napo | Reserva Biológica Colonso Chalupas | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Azuela | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Río Sardinas | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Sendero al Río Misahuallí | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Abitagua | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera | Roze 1996 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Shell | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Río Zuñac, trail to reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | San Francisco de Mapoto | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Ulba | Valencia et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Alto Machinaza | Almendáriz et al 2014 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | La Canela, 8 km E of | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Maycu Reserve | This work |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Nambija | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Permatree | iNaturalist |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Valle del Quimi | Betancourt et al. 2018 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza, 14 km NE of | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Yantzaza, vía a Pindal | Valencia et al. 2016 |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zumba | Photo by Darwin Núñez |

| Perú | Amazonas | Cordillera del Cóndor i Peru | Campbell & Lamar 2004 |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Namballe, 7 km S of | iNaturalist |

| Perú | Cajamarca | Perico | Schmidt 1936 |