Published April 7, 2023. Updated December 12, 2023. Open access. | Purchase book ❯ |

Blunt-headed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus brevifrontalis)

Reptiles of Ecuador | Sauria | Alopoglossidae | Alopoglossus brevifrontalis

English common names: Blunt-headed Shade-Lizard, Boulenger’s Largescale Lizard, Short-faced Shade Lizard.

Spanish common names: Lagartija sombría hocicorta, lagartija de sombra de frente corta.

Recognition: ♂♂ 16.5 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.2 cm. ♀♀ 16.9 cmMaximum distance from the snout to the tip of the tail. Snout–vent length=6.8 cm..1,2 Aloglossus brevifrontalis is a long and slender lizard that can be distinguished from other Amazonian leaf-litter lizards by having weakly striated (rather than strongly keeled) rectangular dorsal scales (Fig. 1).2–4 All other Amazonian Alopoglossus in Ecuador have mucronate (ending abruptly in a sharp point) dorsal scales.5 This species differs from Arthrosaura reticulata by having four (instead of three) supraocular scales,6 and from Iphisa elegans by having more than two longitudinal rows of dorsal scales.3,7 Adult males of Ecuadorian A. brevifrontalis have shorter bodies than females and also have a bright red ventral coloration.2

Figure 1: Individuals of Alopoglossus brevifrontalis: Santa Rosalía, Vichada department, Colombia (); Reventador Volcano, Sucumbíos province, Ecuador (); Pacto Sumaco, Napo province, Ecuador (). j=juvenile.

Natural history: Alopoglossus brevifrontalis is a rarelyTotal average number of reported observations per locality less than ten. encountered lizard that occurs in old-growth and moderately disturbed rainforest and lower-montane forests, as well as in clearings near forest borders.1,8 Blunt-headed Shade-Lizards are diurnal, cryptozoic (preferring moist, shaded microhabitats), and semi-fossorial.9 They forage on and under leaf-litter, and hide under logs and rocks3,5 or in soil within a few centimeters from the surface.1,2,5 The diet includes spiders, insects, and insect larvae.10 Predators include the frog Ceratophrys cornuta11 and the snake Taeniophallus brevirostris.9 When threatened, these shy lizards flee into the leaf-litter; if captured, they may bite or shed the tail.1 Two-egg clutches have been recorded,7 and breeding females have been found throughout the year.2,10

Conservation: Least Concern Believed to be safe from extinction given current circumstances..12 Alopoglossus brevifrontalis is included in this category mainly on the basis of the species’ wide distribution, presence in protected areas, and presumed large stable populations.12 In the Brazilian Amazonia, about 54% of the occurrence area of A. brevifrontalis is inside protected areas and about 95% of its original forest habitat is still standing.13 The status in Ecuador is similar. Based on recent maps of vegetation cover of the Amazon basin,14 the majority (~87%) of the species’ habitat remains forested. Thus, A. brevifrontalis is considered to be facing no major immediate extinction threats.

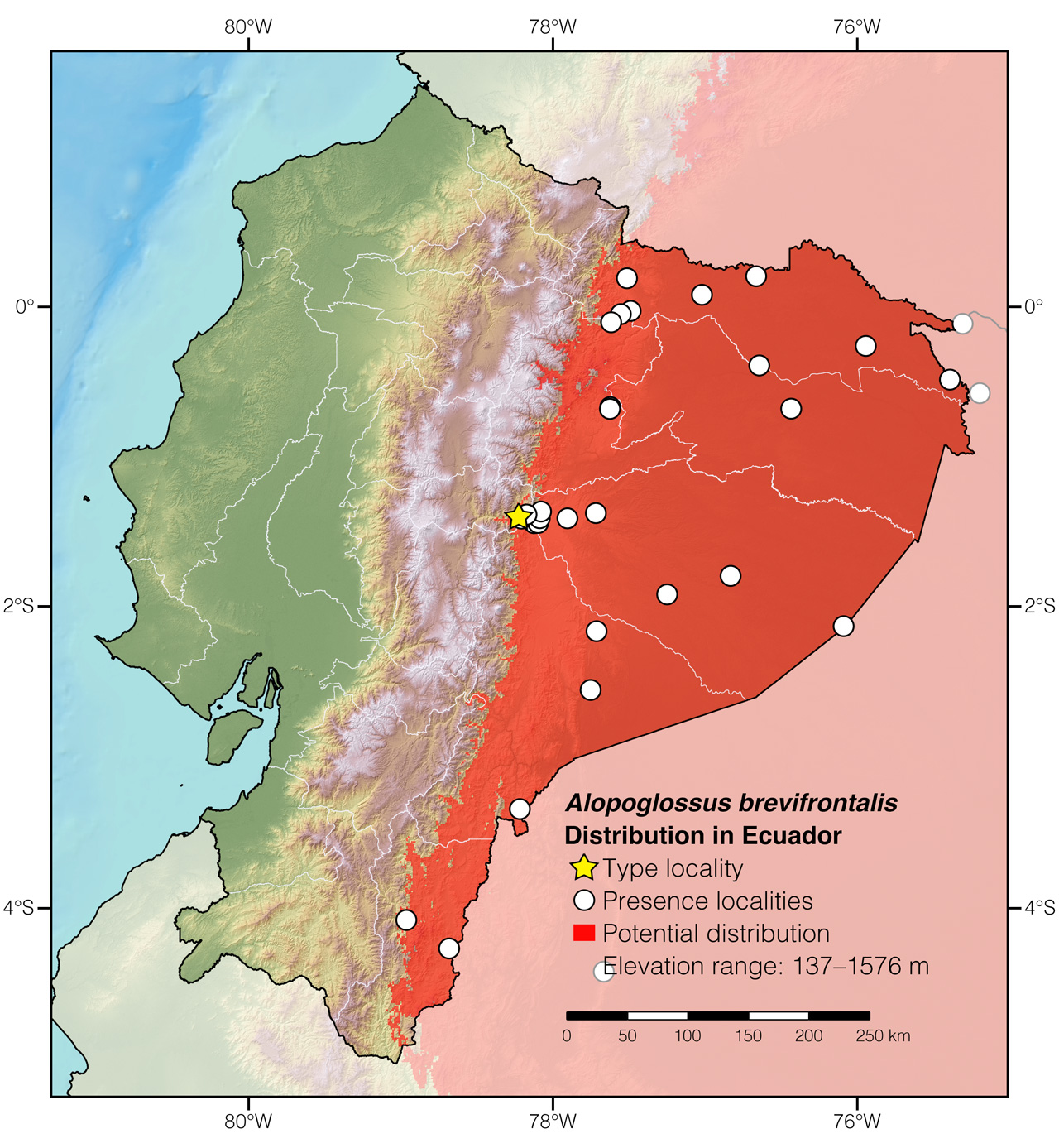

Distribution: Alopoglossus brevifrontalis is native to an area of approximately 1,645,585 km2 in the Amazon of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador (Fig. 2), French Guiana,15 Perú, and Suriname.13

Figure 2: Distribution of Alopoglossus brevifrontalis in Ecuador. The star corresponds to the type locality: El Topo. See Appendix 1 for a complete list of the presence localities included in the map.

Etymology: The generic name Alopoglossus is derived from the Greek words alopekia (=bare) and glossa (=tongue)16 and refers to the lack of scale-like papillae in the tongue of these lizards.2,17 The specific epithet brevifrontalis is derived from the Latin words brevis (=short), front (=snout), and the suffix -alis (=pertaining to).16 It refers to the short snout.18

See it in the wild: Even though they are not the most common leaf-litter lizards wherever they occur, Blunt-headed Shade-Lizards can be seen with relative ease in Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary and Sumak Kawsay In Situ Reserve. These shy reptiles may be located by turning over rocks and rotten logs or by removing leaf-litter inside the forest.

Authors: Jose VieiraaAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

Photographers: Jose Vieira,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,bAffiliation: ExSitu, Quito, Ecuador. Duvan Zambrano,dAffiliation: Universidad del Tolima, Ibagué, Colombia. Amanda Quezada,aAffiliation: Tropical Herping (TH), Quito, Ecuador.,dAffiliation: Laboratorio de Herpetología, Universidad del Azuay, Cuenca, Ecuador. and Alejandro ArteagacAffiliation: Fundación Khamai, Reserva Arlequín, Ecoruta Paseo del Quinde km 56, Santa Rosa de Mindo, Pichincha 171202, Ecuador.

How to cite? Vieira J, Arteaga A (2023) Blunt-headed Shade-Lizard (Alopoglossus brevifrontalis). In: Arteaga A, Bustamante L, Vieira J (Eds) Reptiles of Ecuador: Life in the middle of the world. Available from: www.reptilesofecuador.com. DOI: 10.47051/TRWN4953

Literature cited:

- Field notes, Reptiles of Ecuador book project.

- Harris DM (1994) Review of the teiid lizard genus Ptychoglossus. Herpetological Monographs 8: 226–275. DOI: 10.2307/1467082

- Duellman WE (1978) The biology of an equatorial herpetofauna in Amazonian Ecuador. Publications of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas 65: 1–352.

- Castro Herrera F, Ayala SC (1988) Saurios de Colombia. Unpublished, Bogotá, 692 pp.

- Avila-Pires TCS (1995) Lizards of Brazilian Amazonia (Reptilia: Squamata). Zoologische Verhandelingen 299: 1–706.

- Diago-Toro MF, García-Cobos D, Brigante-Luna GD, Vásquez-Restrepo JD (2021) Fantastic lizards and where to find them: cis-Andean microteiids (Squamata: Alopoglossidae & Gymnophthalmidae) from the Colombian Orinoquia and Amazonia. Zootaxa 5067: 377–400. DOI: 10.11646/zootaxa.5067.3.3

- Vitt LJ, Magnusson WE, Avila-Pires TCS, Pimentel Lima A (2008) Guide to the lizards of Reserva Adolpho Ducke, Central Amazonia. Áttema Design Editorial, Manaus, 176 pp.

- Camper JD, Torres-Carvajal O, Ron SR, Nilsson J, Arteaga A, Knowles TW, Arbogast BS (2021) Amphibians and reptiles of Wildsumaco Wildlife Sanctuary, Napo Province, Ecuador. Check List 17: 729–751.

- Dixon JR, Soini P (1986) The reptiles of the upper Amazon Basin, Iquitos region, Peru. Milwaukee Public Museum, Milwaukee, 154 pp.

- Duellman WE (2005) Cusco amazónico: the lives of amphibians and reptiles in an Amazonian rainforest. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 433 pp.

- Duellman WE, Lizana M (1994) Biology of a sit-and-wait predator, the leptodactylid frog Ceratophrys cornuta. Herpetologica 50: 51–64.

- Calderón M, Perez P, Avila-Pires TCS, Aparicio J (2019) Alopoglossus brevifrontalis. The IUCN Red List of threatened species. Available from: www.iucnredlist.org. DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T203062A2759731.en

- Ribeiro-Júnior MA, Amaral S (2016) Diversity, distribution, and conservation of lizards (Reptilia: Squamata) in the Brazilian Amazonia. Neotropical Biodiversity 2: 195–421. DOI: 10.1080/23766808.2016.1236769

- MapBiomas Amazonía (2022) Mapeo anual de cobertura y uso del suelo de la Amazonía. Available from: www.amazonia.mapbiomas.org

- Dewynter M, Godé L, Girardot T, Courtois EA (2020) First record of Ptychoglossus brevifrontalis Boulenger, 1912 (Squamata, Alopoglossidae) in French Guiana. Check List 16: 155–161. DOI: 10.15560/16.1.155

- Brown RW (1956) Composition of scientific words. Smithsonian Books, Washington D.C., 882 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1885) Catalogue of the lizards in the British Museum. Taylor & Francis, London, 497 pp.

- Boulenger GA (1912) Descriptions of new reptiles from the Andes of South America, preserved in the British Museum. Annals and Magazine of Natural History 10: 420–424.

Appendix 1: Locality data used to create the distribution map of Alopoglossus brevifrontalis in Ecuador (Fig. 2). Go to the section on symbols and abbreviations for a list of acronyms used. Asterisk (*) indicates type locality.

| Country | Province | Locality | Source |

| Colombia | Amazonas | El Encanto | SINCHI 3316; Caicedo Portilla et al. 2023 |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Comunidad Shuar Kunkuk | Facebook photo by Gustavo Pazmiño |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Macuma | UIMNH 66151; not examined |

| Ecuador | Morona Santiago | Río Cusuime | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Hidroeléctrica Coca Codo Sinclair | MECN & ENTRIX 2009–2013 |

| Ecuador | Napo | Pacto Sumaco | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Napo | Wild Sumaco Wildlife Sanctuary | Camper et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Orellana | Yasuni Scientific Station | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Abitagua | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Mera, environs of | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Oglán Alto | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pozo Danta | Ortega-Andrade 2010 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Pucayacu (Río Pucayacu) | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Arajuno, headwaters of | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Río Corrientes | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Sumak Kawsay In Situ | Bentley et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Pastaza | Tzarentza | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Boca del Río Cuyabeno | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | El Reventador | Avila-Pires 1995 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Garzacocha | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Hostería Reventador | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | La Balsareña | iNaturalist; photo examined |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Limococha Biological Reserve | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Puerto Libre | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Río Putumayo | Diago-Toro et al. 2021 |

| Ecuador | Sucumbíos | Santa Cecilia | Harris 1994 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | El Topo* | Boulenger 1912 |

| Ecuador | Tungurahua | Reserva Río Zuñac | Online multimedia |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Nangaritza | Reptiles of Ecuador book database |

| Ecuador | Zamora Chinchipe | Zamora | Harris 1994 |

| Perú | Amazonas | Boca del Río Santiago | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |

| Perú | Loreto | Centro Unión | Harris 1994 |

| Perú | Loreto | Redondococha | Yánez-Muñoz & Venegas 2008 |

| Perú | Loreto | Río Ampiyacu | Ribeiro-Júnior & Amaral 2016 |